54th Massachusetts: Freedom Under Arms

Posted on 30th August 2021

President Lincoln had discussed emancipating the slaves with his Cabinet as early as July 1862, but uncertain what the reaction to doing so would be in the North he decided to wait for Union success on the battlefield before taking the issue any further. That opportunity came on 17 September when despite General George McClelland’s best efforts to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory a tactical success was achieved at the bloody Battle of Antietam which forced the invading Confederate Army to withdraw back across the Potomac River.

Five days later, on 22 September, a Proclamation was issued to little fanfare and with none of the rhetorical embellishment of which Lincoln was well capable for he knew that any attempt to abolish slavery even in the immediate afterglow of victory would be controversial:

That on the first day of January in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

But it was vague and imprecise, the Proclamation did not appear to abolish the institution of slavery but merely release those slaves who had fallen into Union hands and were already being treated as contraband of war, and in those States in a condition of rebellion while an exception was made for those slave-owning States that had remained in the Union and for the recently created State of West Virginia that had broken away from the rest of Virginia following its refusal to secede and had since applied to join the Union.

Under the guidelines set down in the Emancipation Proclamation of the 4.1 million slaves in bondage more than 900,000 would have remained so.

Nonetheless, Lincoln had been right to err on the side of caution before issuing it, he was aware of its likely political impact and that it had provided a war previously fought solely for the preservation of the Union with a new moral dimension.

It was not greeted warmly by many in the North who had no greater love for the negroe than their brethren in the South particularly in the run-down areas of the major cities where they competed with poor whites for work. Indeed, there were riots in New York and Baltimore while several Union regiments laid down their arms and went home believing this was not the cause they were fighting for. Many others were angry with the President for acting unconstitutionally and beyond his powers and the Proclamation was greeted with mixed sometimes openly hostile newspaper editorials.

It appeared to some that he had changed the United States Constitution, the sanctity and preservation of which they were supposedly fighting, by Executive Order without consultation or recourse to Congress.

The reaction to the Proclamation in the South was predictably one of outrage. It seemed to them that not only was President Lincoln inciting slaves to rise up and murder them in their beds, but he was violating their property rights, the very property upon which Southern prosperity was based. It had also dealt them another more significant and devastating blow for with the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation all prospect of foreign recognition of the Confederacy and intervention on their behalf ended. Neither Britain nor France could be seen to be actively supporting the preservation of slavery.

The Proclamation was greeted enthusiastically by abolitionists however, though some thought it had not gone far enough, and there was now a clamour for the formation of black regiments to fight in the Union cause. After all, if the war was now to be about the abolition of slavery, then those who had been its primary victim should be permitted to fight to free those who still were.

The 54th Massachusetts wasn’t the first Union regiment to be recruited from amongst ex-slaves and free black men that honour goes to the 1st South Carolina Volunteers but that was an essentially irregular unit.

It was formed in March 1863, at the behest of the Governor of Massachusetts John Albion Andrew, a fervent abolitionist and close friend of the writer, political activist, and ex-slave Frederick Douglass.

There was little enthusiasm in Government circles for the formation of black regiments and so much of the money for doing so was raised by the abolitionist movement itself through donations and public subscription.

Also, if there were to be black soldiers in the Union Army then the Secretary of War Edwin M Stanton insisted that they must be led by white Officers. There was little opposition to this, and Governor Andrew busied himself recruiting the right men for the job. His choice of Commanding Officer fell upon 25-year-old Robert Gould Shaw; though he was at the time only a Captain in the Union Army, Shaw came from a wealthy family who were prominent abolitionists in his hometown of Boston, and Governor Andrew was a close personal friend of his father.

Andrew was also to make sure that most of the regiments other 29 Officers also came from abolitionist families including its second-in-command Norwood Penrose Hallowell.

Shaw, who had been approached by his father about taking command of the first black regiment, initially declined the offer considering it a dubious honour at best. He had in the past been inclined to use the racial terminology ascribed to black people at the time and shared many of the prejudices that were prevalent, but he was nonetheless anti-slavery. Realising what it meant to his father and to the cause of emancipation he soon reversed his decision and was subsequently promoted to Colonel.

Much to the disappointment of the abolitionists there was no rush to enlist. Ex-slaves were rare in Boston for though it had long been a centre of the underground that spirited runaway slaves from the South it was also a target for slave catchers and bounty hunters and any escaped slaves in the city were quickly moved on. Free black men who had jobs and families to support were disinclined to put either at risk to get involved in what they largely saw as a white man’s war and so prominent black abolitionists were sent to cities throughout the North on what became effectively a recruitment drive. Frederick Douglas went to New York, Martin Delany to Michigan and John Rock to New England.

So unpopular among the white population was the notion of black men being under arms that much of the recruitment had to be done in secret, but the campaign proved a great success nonetheless and in the end so many men were encouraged to enlist in the regiment that Andrew and Shaw were in the almost unique position of being able to accept only the fittest and ablest candidates.

The regiment was trained at Camp Meigs just outside Boston where they became something of a local curiosity, children would gather to watch them, journalists wrote about them at great length and abolitionist women would visit with food and warm winter clothing along with their best wishes.

Despite the circus surrounding its formation Shaw was impressed by the commitment and discipline of his men. He believed they would make good soldiers and was determined they should have the opportunity prove themselves.

Few outside of abolitionist circles however ever expected them to fight believing they would only be used for manual labour, the digging of trenches and latrines, and the burying of the dead.

On 23 December 1862, the Confederate President Jefferson Davis issued a proclamation of his own declaring that the Union was behaving beyond the rules of war and that those areas of the South under Union occupation were subject to criminal activity. The formation of a black regiment was merely further proof that Abraham Lincoln was not fighting to preserve the Union but to terrorise and humiliate the South by encouraging slaves to rebel and turn on their masters and sending black troops to murder white children and ravage white women.

The following year he reinforced his previous proclamation by stating that those black men captured in the service of the Union would be returned to slavery while those captured in uniform would be liable to execution. Likewise, any white Officers found to be in command of black troops would be considered guilty of inciting slave insurrection and be hanged.

No one could be under any illusion what this meant, that to serve in a black regiment carried a death sentence. Even so, morale remained high.

The 54th Massachusetts Regiment passed muster on 28 May 1863, a few days later they were transported South landing at Buford, South Carolina, on 3 June, where they were immediately put to doing manual labour. Colonel Shaw was as outraged; this was not what they had been trained for and he argued long and hard for them to see combat.

On 11 June they were permitted to accompany the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers, another black regiment, under the command of a fanatical abolitionist Colonel James Montgomery on a raid to the town of Darien in Georgia. Montgomery took little pride in his men, and they were effectively a regiment in name only, as far as he was concerned they were neither soldiers nor people to be respected but merely the instruments of God’s punishment.

Darien was undefended and of little strategic value, nevertheless Montgomery ordered it to be looted and set alight. When Shaw was ordered his men to do likewise, he demurred but in the end he had little choice but to comply. Even so, as Montgomery’s men broke ranks and looted for all they were worth the men of the 54th Massachusetts maintained discipline and took only what could be used back in camp. This was not what they had enlisted for, and Colonel Shaw was later to refer to the raid on Darien as a Satanic Act.

On 30 June, the troops of the 54th were mustered to sign for and receive their pay only to be told, despite previous assurances to the contrary, that they were to receive just $10 dollars a week with $3 dollar withheld for the cost of clothing. This was less than a white soldier who also had no money withheld for clothing. Further humiliation was heaped on this decision when it was discovered that $7 dollars a month was the same amount of money as a worker in a labour battalion received.

The men refused to accept their pay and despite this being technically mutinous Colonel Shaw and the other white Officers supported them. When the State of Massachusetts vowed to make up the difference, they still refused to accept it.

They eventually won their dispute but not until September 1864, when Congress agreed to equal pay for white and black soldiers alike to be backdated to the time of enlistment.

This did little to help the families of the soldiers back home many of whom in the year between were reduced into penury with some living on charity and others forced into the workhouse.

On the 8 July, the 54th Massachusetts participated in a landing on James Island near Charleston.

The landing was a feint designed to draw enemy forces away from defending the city, but it wasn’t expected that it would lead to any fighting. However, on 16 July Confederate troops made a surprise attack upon the Union camp and it was the 54th that took the brunt of the assault. In a fierce struggle often fought hand-to-hand the black soldiers not only held their ground but forced the Confederates to withdraw and break off the attack. It had only been a short, sharp skirmish but it was the first time they had seen action and they were widely praised by those who witnessed it with even the Southern press feeling compelled to report that black men had fought better than many of the white soldiers present.

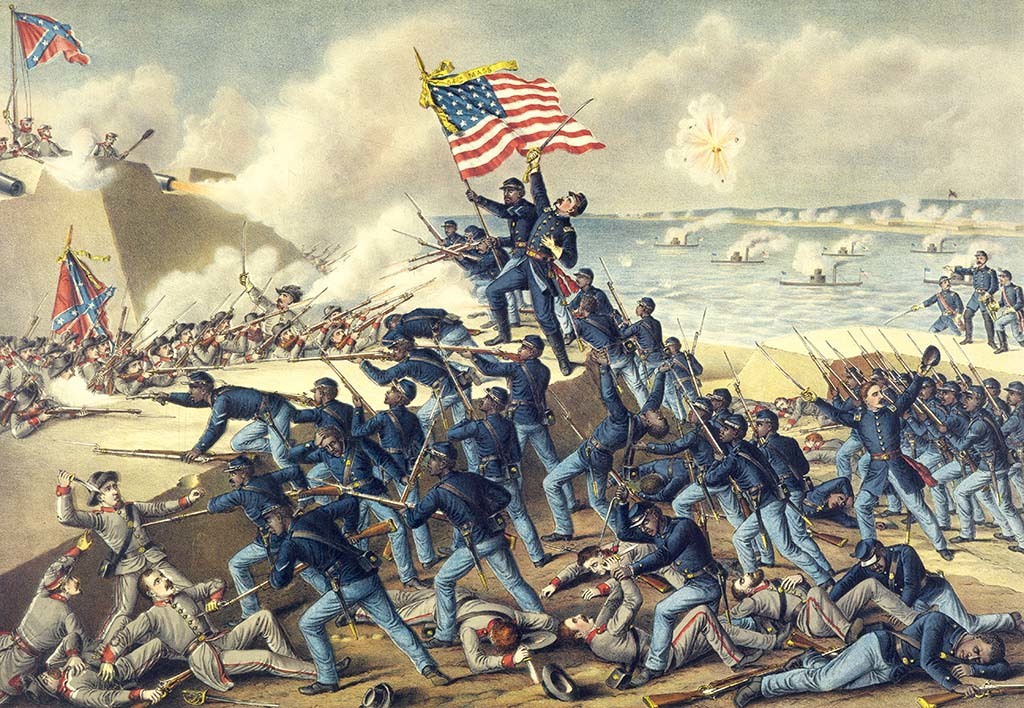

Despite suffering 42 killed and wounded their blood was up and just two days after the engagement on James Island the 54th were ordered to spearhead an assault against Fort Wagner that dominated the southern approach to Charleston Harbor.

An attack had been made the previous week but had been repulsed with heavy casualties, so whether the 54th Massachusetts had been assigned the task of leading the attack because Colonel Shaw had sought the honour for his regiment or because black soldiers were seen as being expendable remains uncertain.

Fort Wagner was a formidable sand construction armed with cannon and howitzers and had a garrison of 1,800 mostly native South Carolinians determined to defend their capital. It was also surrounded by a moat of sharpened wooden spikes, a water filled ditch and a high parapet that had to be scaled before the walls of the fort itself could be reached. It was commanded by the experienced Virginian William Booth Taliaferro who had previously served in the Eastern theatre under the legendary General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

The assault on Fort Wagner would have to be made over difficult terrain. First the troops would have to advance along a beach only 60 yards wide with the sea to the east and a marshy swamp to the west where they would come under heavy enfilading fire before they could even turn and begin their assault on the fort.

The 54th Massachusetts were to be supported by the 6th Connecticut, 3rd New Hampshire, 76th Pennsylvania, 9th Maine and 48th New York regiments, more than 5,000 men in total. The attack would follow a sustained barrage by 6 Union Ironclads moored just offshore.

This was intended to cause chaos within the fort but with the firing often inaccurate, the sand construct of the fort absorbing the impact of the shells and the Confederates in shelters within it was largely ineffective and they were to suffer only 8 men killed throughout the entire bombardment.

As dusk settled on the evening of 18 July the 54th Massachusetts formed up on the beach with flags flying and band playing but there was a sense of apprehension. The beach was too narrow for more than one regiment to advance at a time so at the beginning at least they would be on their own.

General George Strong, in overall command of the assault now rode forward and pointing towards the fort in the distance asked, “Is there one man here who thinks they will not be sleeping in that fort tonight?” Cries of “no” and “we’ll be there” could be heard coming from the ranks. He then ordered the flag-bearer to step forward and said, “If this man should fall who will lift the flag and carry it forward?” After a brief pause Colonel Shaw replied in a firm voice, “I will, Sir” A roar of approval rose up from the mass of men assembled.

At around 7.45 pm as the barrage from the Ironclads moored offshore ceased and with Colonel Shaw very much at the forefront the advance began.

They came under cannon fire almost immediately and Shaw ordered them to march at the quick but moving parallel to the fort rather than advancing directly upon it the formation began to break down as men huddled together for protection and sought shelter where they could. Fearing that the attack might falter before it had even begun Shaw shouted to his men, rallying them at every point, and urged them to remain strong and move faster.

As the fort came into view Shaw gave the order to charge earlier than would normally be the case and with bayonets fixed, they now ran as fast as they could towards the defences rarely stopping to fire and yelling at the top of their voices. As they got to within 200 yards of the fort, General Taliaferro gave the order for the massed ranks of Confederate troops manning its ramparts to open fire.

Struggling over the wooden stakes and slowed by the water-filled ditch they were sitting targets as the musket fire cut swathes in their ranks and such was the intensity of fire the Shaw's men wavered and went to ground. The attack had stalled, and they had not even yet reached the parapet.

By this time darkness had descended and the pitch black was only lit up by the firing of muskets and the explosion of grenades.

Determined that the attack should not fail Colonel Shaw rose to his feet and waving his sword above his head shouted “Forward 54th, forward! As he turned to run up the sandbank he was seen to stagger and reel before falling back dead shot three times through the chest.

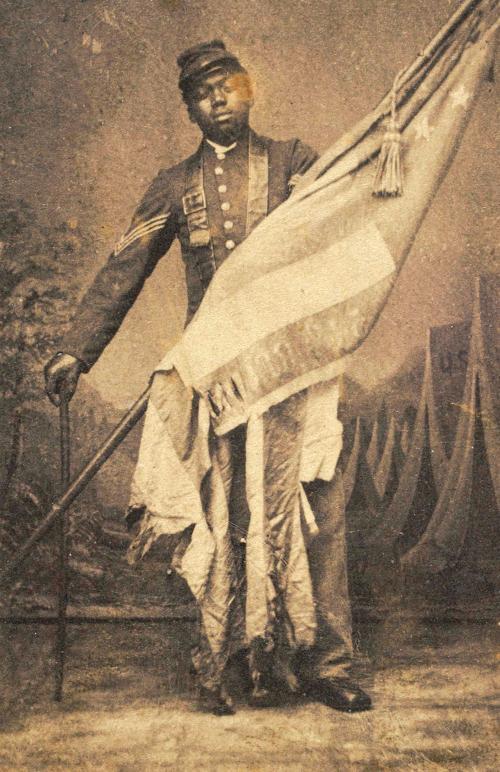

Sergeant William Carney seeing that the flag-bearer had fallen now took it up and planting it firmly in the ground used it as a rallying point for the regiment, and some did indeed rally, enough at least for the attack to continue.

The parapet was breached, and a small section of the wall taken, the fighting was bitter and hand-to-hand with no quarter given by either side but there were too few troops remaining of the shattered 54th for there to be any hope of success and with no time to order a retreat men simply fled the field and tried to make it back to their own lines as best they could.

Sergeant Carney was one of the last to withdraw but before he did so he gathered up the flag determined that it should not fall into Confederate hands and returning to the lines with it still in his grasp said: "Boys, I only did my duty, the old flag never touched the ground."

The white regiments following behind the 54th fared even worse and few made it anywhere near the fort’s ramparts and in the darkness, confusion, and amid the carnage already wrought chaos ensued when unable to make out friend from foe the 100th New York fired volley after volley of musket fire into the backs of their Union comrades.

The attack on Fort Wagner had been a fiasco and as the Union troops withdrew in some disorder nothing had been gained at a terrible cost.

For the loss of just 36 men killed and 145 wounded General Taliaferro had inflicted a crushing defeat upon the Union Army that had endured over 1,500 casualties.

The 54th Massachusetts Regiment had lost its Commanding Officer and 106 men killed, 149 wounded, and 15 captured but it had proved itself in battle and moreover had won the respect of those white soldiers fighting alongside them.

For his heroism at Fort Wagner, William Carney became the first black soldier to be awarded the medal of honour though he was not actually presented with it until 23 May 1900, a full 37 years after the award had first been bestowed upon him and just 8 years prior to his death.

Following the battle, the Union Army requested that Robert Gould Shaw’s remains be returned to his family. The Confederate Commander in Charleston Johnson Hagood refused replying that: “He has been buried with his niggers.” It was not intended as a compliment. Informed, of the decision Shaw’s father declared that he was indeed honoured and that there could be no better resting place for his son.

The defeat at Fort Wagner did not signal the end of the fighting for the 54th Massachusetts and on 20 February 1864, they participated in the bloody Battle of Olustee in Florida where they once more came up against William Taliaferro, and then at the disastrous Battle of Honey Hill in November. They fought for one last time at Boykin’s Mill on 19 April 1865, which was to be one of the final engagements of the war.

The formation of the 54th Massachusetts was just the beginning of black participation in the war, and in total 179,000 black men were to serve in the Union Army or 10% of those who fought whilst a further 19,000 served in the navy. Of those who enlisted some 40,000 were to die – a freedom granted had been paid for in blood.

The 54th Massachusetts returned to Boston at the end of the war to considerable acclaim but no longer deemed necessary following the cessation of hostilities the regiment was disbanded on 4 August 1865.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, War

Share this post: