A Mexican Remembers the Alamo

Posted on 28th April 2021

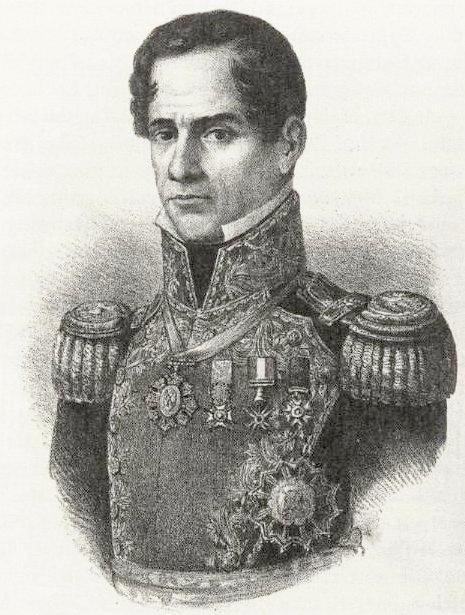

In 1835, Texas belonged to Mexico but there was a growing sense in the region that it needn’t be so. A recent influx of Americans with their clearly defined notions of liberty and Mexicans already resident disgruntled at the autocratic rule of General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna saw tensions mount and following a series of skirmishes with the Mexican Army it was forced to abandon the region. Their absence saw an expression of anger become a fully-fledged movement for independence. But the Mexicans would be back.

Santa Anna had no intention of entering into negotiation with those he considered little better than pirates and by early 1836 he had returned with a fresh, fully equipped and formidable army determined to crush the rebellion. The Texians, a rag-tag collection of regular soldiers, volunteers, and adventurers were nevertheless just as determined to be free.

By the last week of February, Santa Anna’s army stood before the Mission Station known as the Alamo, a broken down, ramshackle old Church and its surround that had been hastily fortified for defence. Inside were some 200 mostly volunteer fighters under the command of William Barret Travis. Also at the Alamo were two legendary figures of the West, Jim Bowie and Davy Crockett. Their presence would make for an exhaustive mythology intended for the most part to praise but also to demean.

Santa Anna would offer no quarter and those defending the Alamo would die to a man, whether some did so less heroically than others is irrelevant in that they were all killed in the cause they were fighting for. There are then few descriptions of the fighting from the Texian side other than the memories of the women and non-combatants who survived.

This account is from a serving Officer in Santa Anna’s army:

"On this same evening, a little before nightfall, it is said that Barret Travis, commander of the enemy, had offered to the general-in-chief, by a woman messenger, to surrender his arms and the fort with all the materials upon the sole condition that his own life and the lives of his men be spared. But the answer was that they must surrender at discretion, without any guarantee, even of life, which traitors did not deserve. It is evident, that after such an answer, they all prepared to sell their lives as dearly as possible. Consequently, they exercised the greatest vigilance day and night to avoid surprise.

On the morning of March 6, the Mexican troops were stationed at 4 o'clock, A.M., in accord with Santa Anna's instructions. The artillery, as appears from these same instructions, was to remain inactive, as it received no order; and furthermore, darkness and the disposition made of the troops which were to attack the four fronts at the same time, prevented its firing without mowing down our own ranks. Thus the enemy was not to suffer from our artillery during the attack. Their own artillery was in readiness. At the sound of the bugle they could no longer doubt that the time had come for them to conquer or to die. Had they still doubted, the imprudent shouts for Santa Anna given by our columns of attack must have opened their eyes.

As soon as our troops were in sight, a shower of grape and musket balls was poured upon them from the fort, the garrison of which at the sound of the bugle had rushed to arms and to their posts. The three columns that attacked the west, the north, and the east fronts, fell back, or rather, wavered at the first discharge from the enemy, but the example and the efforts of the officers soon caused them to return to the attack. The columns of the western and eastern attacks, meeting with some difficulties in reaching the tops of the small houses which formed the walls of the fort, did, by a simultaneous movement to the right and to left, swing northward till the three columns formed one dense mass, which under the guidance of their officers, endeavoured to climb the parapet on that side.

This obstacle was at length overcome, the gallant General Juan V Amador being among the foremost, meantime the column attacking the southern front under Colonels Jose Vicente Minon and Jose Morales, availing themselves of a shelter, formed by some stone houses near the western salient of that front, boldly took the guns defending it, and penetrated through the embrasures into the square formed by the barracks. There they assisted General Amador, who having captured the enemy's pieces turned them against the doors of the interior houses where the rebels had sought shelter, and from which they fired upon our men in the act of jumping down onto the square or court of the fort. At last they were all destroyed by grape, musket shot and the bayonet.

Our loss was very heavy. Colonel Francisco Duque was mortally wounded at the very beginning, as he lay dying on the ground where he was being trampled by his own men, he still ordered them on to the slaughter. This attack was extremely injudicious and in opposition to military rules, for our own men were exposed not only to the fire of the enemy but also to that of our own columns attacking the other fronts; and our soldiers being formed in close columns, all shots that were aimed too low, struck the backs of our foremost men. The greatest number of our casualties took place in that manner; it may even be affirmed that not one fourth of our wounded were struck by the enemy's fire, because their cannon, owing to their elevated position, could not be sufficiently lowered to injure our troops after they had reached the foot of the walls. Nor could the defenders use their muskets with accuracy, because the wall having no inner banquette, they had, in order to deliver their fire, to stand on top where they could not live one second.

The official list of casualties, made by General Juan de Andrade, shows: officers 8 killed, 18 wounded; enlisted men 52 killed, 233 wounded. Total 311 killed and wounded. A great many of the wounded died for want of medical attention, beds, shelter, and surgical instruments.

The whole garrison were killed except an old woman and a negro slave for whom the soldiers felt compassion, knowing that they had remained from compulsion alone. There were 150 volunteers, 32 citizens of Gonzales who had introduced themselves into the fort the night previous to the storming, and about 20 citizens or merchants of Bexar."

Share this post: