A Victorian Christmas

Posted on 11th October 2021

Christmas is not of course a Victorian creation though many of those aspects of what we now consider a traditional Christmas are Victorian in origin.

The Winter Solstice has Pagan roots, a Celtic festival overseen by a Druidical priesthood where people would gather, animals would be sacrificed, and incantations made to the Gods for a safe passage through the frightful time without harvest, of dark nights, and freezing cold. Some of the traditions we still associate with Christmas come from this time and the Celtic veneration of nature, and of trees and foliage in particular.

The Yuletide Log that was to be kept burning for the full twelve days of the festival, standing beneath the mistletoe for good fortune, or to steal a kiss, the holly and the ivy all come from this time.

There had also long been a Father Christmas type figure that is believed to have originated with the God Odin but since the early nineteenth century has been most closely associated with the Dutch Sinterklaas, though he was not necessarily always the benevolent figure we recognise today.

In AD 354, Pope Julius I declared 25 December to be Christ’s birthday though the first recorded reference to Christmas is not until 1043 and it was to evolve down the centuries but now adopted as a Christian festival it was to become an arena of conflict fought out between the demands of solemn piety and the desire for wild celebration.

By the Tudor era Christmas was firmly established as a time to be ‘hale and hearty’, to give as well as to receive, and for old enmities to be forgotten if only temporarily with the grandeur of the Manor House celebration replicated by the poor and impoverished, a pale imitation perhaps if only in the material not the ephemeral. But there would be a backlash to all this extravagance.

In 1644, at the height of the Civil War in England the influential Puritan preacher and politician Philip Stubbs wrote: “More mischief is at that time committed than in all the year besides. What dicing and carding, what eating and drinking, what banqueting and feasting is then used to the greatest dishonour of God and the impoverishment of the realm.”

An Act of Parliament soon followed banning all celebration of Christmas beyond the solemn pieties of Church attendance.

The law could not be implemented until 1647 however, and the effective end of the Civil War but it was to be honoured more in the breach as riots ensued and in towns the length and breadth of the country, shops refused to open on Christmas Day, labourers absented themselves from work in the fields, and decorations would appear overnight only to be torn down by the Authorities in the morning.

The opposition to the banning of Christmas would result in the thirty day siege of Colchester but it would eventually be returned to the people upon the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660.

The Christmas we recognise today however, is most closely associated with the author Charles Dickens and indeed is often referred to as Dickensian.

His novel, A Christmas Carol published on 19 December 1843, presents an evocative, haunting, but also sentimental vision of Christmas as depicted in visitations from his past to the character of the curmudgeonly old Scrooge.

But it was never Dickens intention to portray a picture postcard ideal vision of Christmas rather it was a warning to everyone of what could so easily be lost. His own impoverished beginnings when he worked as a child in a blacking shop whilst his parents and siblings languished in Marshalsea Debtors Prison were to influence his work throughout his life, but he also recalled happier times and one of his fondest memories was of Christmas when all the family would be together. He remembered with affection the carving of the goose, the giving and receiving of gifts, the playing of games and the singing of songs, but most of all the sense of goodwill and the snow, the endless snow, and it was indeed a White Christmas throughout almost every year of Dickens childhood. It was something he never forgot and Dickens son was later to write of his father at Christmas: “He was always at his best, a splendid host, bright and jolly as a boy and always throwing his heart and soul into everything that was going on, and when he danced there was nothing stopping him.”

Now Dickens feared that in industrialised Britain there was a new God, the God of Profit, and a new tyranny, the Tyranny of the Clock, and that in a world of the audit and the ledger book, of long hours and harsh conditions and hard-headed economic facts, Christmas and the very notion of goodwill to all men was fading from the collective memory.

It was also a time when the mass-migration of the people from the land to the cities and textile towns of the north and elsewhere had seen a sharp reduction in regular Church attendance and it appeared that the material was replacing the spiritual in mankind’s affections.

This was not a sense unique to Dickens but was one shared by many authors, poets, and artists who were appalled at the scarred landscape and social iniquities of the industrialised age and they too sought to revive memories of an often imagined kinder and gentler past far removed from the smoke stacks and red-hot forges of factory Britain.

A Christmas Carol was to prove a great success but it also coincided with other factors that were to remodel Christmas for the modern age.

The revival of Christmas in the public imagination was also in large part down to the young Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert. As a couple they were determined to distance themselves from the trappings of Royalty and embrace a more bourgeois familiarity with the emphasis on hard work and a commitment to family life.

Prince Albert, who was from Germany brought many of the traditions of his homeland to their celebrations of the Christmas festival. It would be a family event and they would be pictured at home surrounded by their children, the tables adorned with small trees known as Tennebaums (the larger Christmas Tree would not be introduced into Britain until later in the Victorian era) decorated with candles and ribbons with beneath them toys and sweets.

These images of the Royal Family so unequivocally embracing Christmas were widely distributed in newspapers and magazines and were to prove hugely popular and have set the tone for the Yuletide Season ever since, and other innovations soon followed.

In 1840, the confectioner Tom Smith travelled to Paris where he discovered the bon-bon, an almond coated in sugar, but it wasn’t the sweet that intrigued him but the way it was sealed in a twist of tissue paper. It wasn’t until 1847 however, that he developed the idea further.

He later told how he had been snoozing before an open fire when he was woken by the popping of the wood and coal as it burned and he imagined replicating that popping sound in the form of a ‘cracker’ sealed like a bon bon that would pop as it was pulled. Smith further developed his idea so it could be shared by children but instead of a sweet he would place inside little toys, and also mottoes and humorous content for the parents.

He then worked tirelessly to produce thousands of his crackers in time for Christmas believing they would prove popular – he was right.

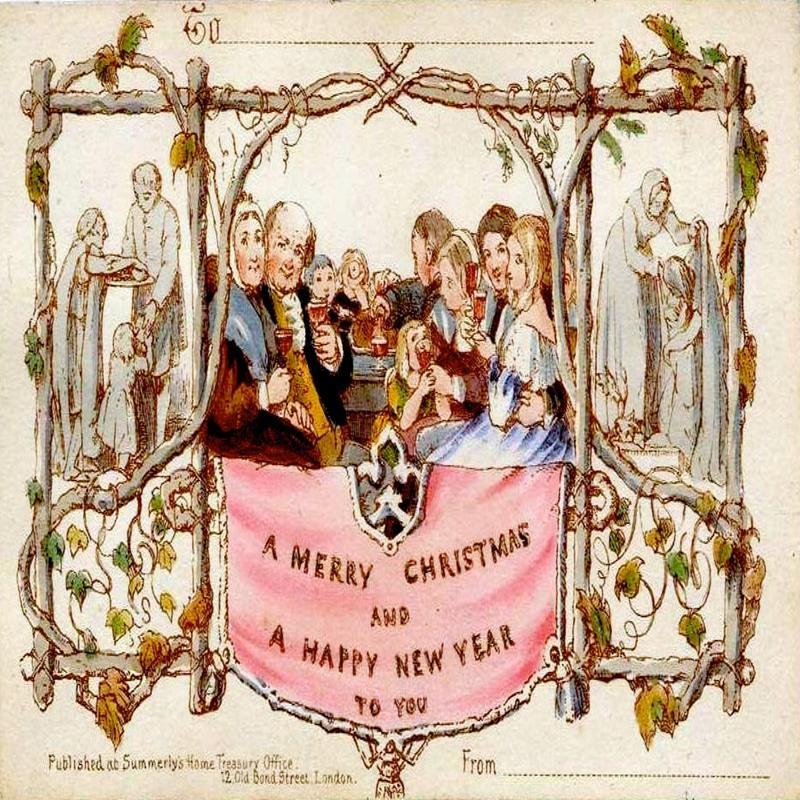

In 1843, Sir Henry Cole tired of having to write so many letters of greeting and felicitation to his friends and family at Christmas thought of the idea of a ready-made card that would merely have to be signed. He commissioned an acquaintance of the artist J. Calcott-Horsley to design just such a card which appeared for the first time that Christmas, the same year as A Christmas Carol was published.

The illustration depicted a family convivially sharing a glass of wine together but these soon developed into portrayals of carol singers church bells, plum puddings, and a great deal of snow.

The creation of the Christmas card also coincided with the introduction of the Penny Post which made the sending of cards affordable to most people and by the 1850’s more than 8 million were being produced and sold every year.

Of course, every Christian country has its own customs and traditions when it comes to celebrating the Christmas festival with some more religious than others but our popular image of it today comes largely from the Victorian era when during a period of revival, it firmly re-established itself as the seminal event in the yearly calendar.

It has become a time not just of reverence and celebration but of reflection and family of hope and charity and as Dickens wrote of Scrooge in his conclusion to A Christmas Carol:

“It was always said of him that he knew how to keep Christmas well, may that also be said of us, and all of us.”

Tagged as: Victorian

Share this post: