Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue

Posted on 12th April 2021

Upon the outbreak of the First World War there were many in senior positions at the Admiralty in London who still appeared blissfully unaware of the threat posed by submarines to their surface vessels.

It was true that submarine technology was still in its infancy and in a world of ever larger and more powerful warships few believed there was much to fear from a poorly armed underwater creeper blind to see and deaf to hear and more talked about as the result of its novelty value than its potency as a weapon of war. All this was to change on the bright, sunny morning of 22 September 1914.

The Armoured Cruisers Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue were by no means obsolete but they were old and slow and considered unfit for service in the Grand Fleet and as a result were assigned the duty of patrol vessels. Although their use in such a role was criticised by some at the time because it left them vulnerable to attack from their faster moving and more modern German equivalent. The mundane nature of their work also meant that they were largely manned not by experienced Royal Navy personnel but young Sea Cadets and semi-trained Reservists.

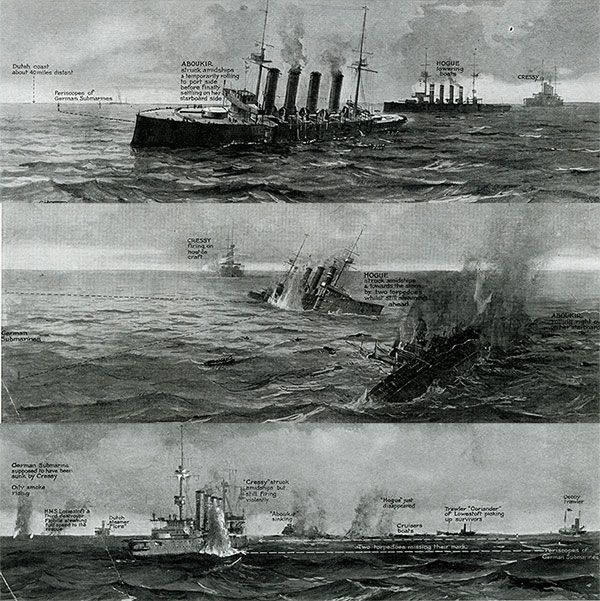

Despite the Squadron being one ship short when the Cruiser Euryalus was forced to return to port to refuel and their Destroyer escort having been delayed by bad weather they had by 06.00 arrived on station in an area known as the Broad Fourteens off the Northern coast of Holland. They were sailing three abreast but had not adopted a zig-zag course as per Admiralty instructions, but then few ships at the time did.

The U-Boat threat had simply not materialised, and the insignificant number of ships lost to torpedo attack had been slow, unarmed merchantmen that were little better than sitting targets. Indeed, U-Boat losses had been such that they appeared to be more of a menace to their own crews than they were the enemy.

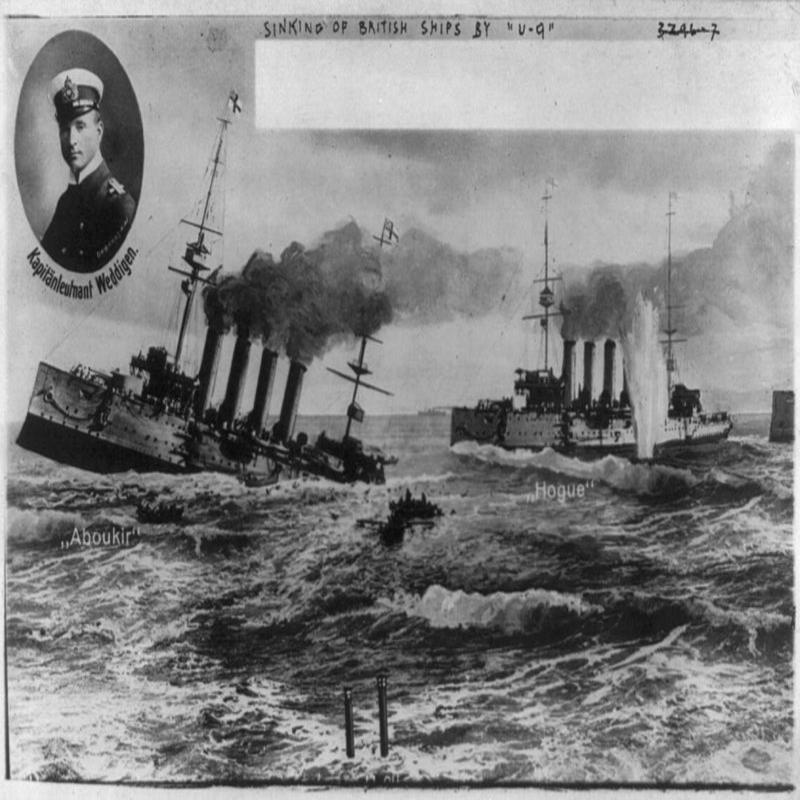

In the area of the Broad Fourteens that day was the single U-9 under the command of Captain Otto Weddingen. He had instructions to intercept and attack British transports, but he had seen none and in truth had spent most of his time sheltering from the inclement weather.

Scanning the horizon that morning he spotted the three British Cruisers sailing in his direction and he was relieved to be presented with the opportunity at last, to do his duty for the Fatherland. He hoped to let loose at least one or two torpedoes before being forced as he expected to take evasive action.

At 06.20 from around 500 yards distant he fired one torpedo which struck the Aboukir on the starboard side flooding its engine room and drowning most of the firemen and stokers.

The sudden loss of power left her unable to manoeuvre and she also took on a severe list which Captain John Drummond tried to re-balance by flooding her port side, but this proved ineffective. Without power and with no prospect of being towed back to port he knew the Aboukir was doomed and gave the order to abandon ship but as it was no longer possible to use the winches to launch the lifeboats many of the crew unable to swim and without lifejackets remained aboard.

Earlier, on all three Cruisers lookouts had been posted to scan the sea for periscopes or any other indication of a U-Boat presence but no such reports had been received and so Captain Drummond believing his ship had hit a mine ordered the other Cruisers to close and take off survivors. Captain Wilmot Nicholson aboard the Hogue, a cautious man by nature reluctantly agreed and pulling her alongside began to lower its boats.

He believed that he had manoeuvred the Hogue into a position where the wreck of the Aboukir would protect it from any possible U-Boat attack but thirty minutes after being struck she suddenly turned-turtle and sank taking 527 men with her leaving the Hogue exposed.

Just as the Aboukir sank beneath the waves two torpedoes struck the Hogue with a tremendous explosion that saw her shudder as if about to break apart before settling in the water. There was barely time to order abandon ship before she too capsized and sank with the loss of 375 lives.

Captain Weddingen who had been manoeuvring U-9 frantically was caught unawares when a sudden weight loss, the result of the two torpedoes he had just fired caused the U-9 to surface.

Vulnerable on the surface Weddingen frantically issued orders for her to dive while the Cressy aware at last that they were under attack by a submarine opened fire and tried to ram the U-9 before she again disappeared beneath the surface but failed to damage her.

Perhaps believing they had sunk or at least frightened off the U-9, the Cressy, in a barely credible act given what had just occurred now also stopped to pick up survivors.

At 07.15 she was struck by a torpedo and again by another fifteen minutes later which caused her to capsize. She was to remain upside down in the water for a further 25 minutes before she too sank taking 560 men with her.

Dutch fishing vessels in the vicinity now refused to close and help those struggling in the water for fear of attack.

Around 08.30 the Steamship Flora arrived and began to pick up survivors along with some nearby trawlers and they were joined two hours later by a number of Destroyers and together they plucked 837 men from the water. Regardless of the frantic rescue efforts in barely an hour three Armoured Cruisers had been sunk and 1,462 lives lost.

One sailor Wenham Wykeham-Musgrove is perhaps the only man to be sunk on three different ships on the same day and survive. He had escaped the Aboukir as she began to sink and fearing that he would be dragged down with her he swam desperately towards the Hogue but just as he was clambering aboard, she too was hit, and he was thrown back into the water. He was then rescued by lifeboat and taken aboard the Cressy when she too was hit and began to capsize. He was eventually found clinging unconscious to a piece of driftwood.

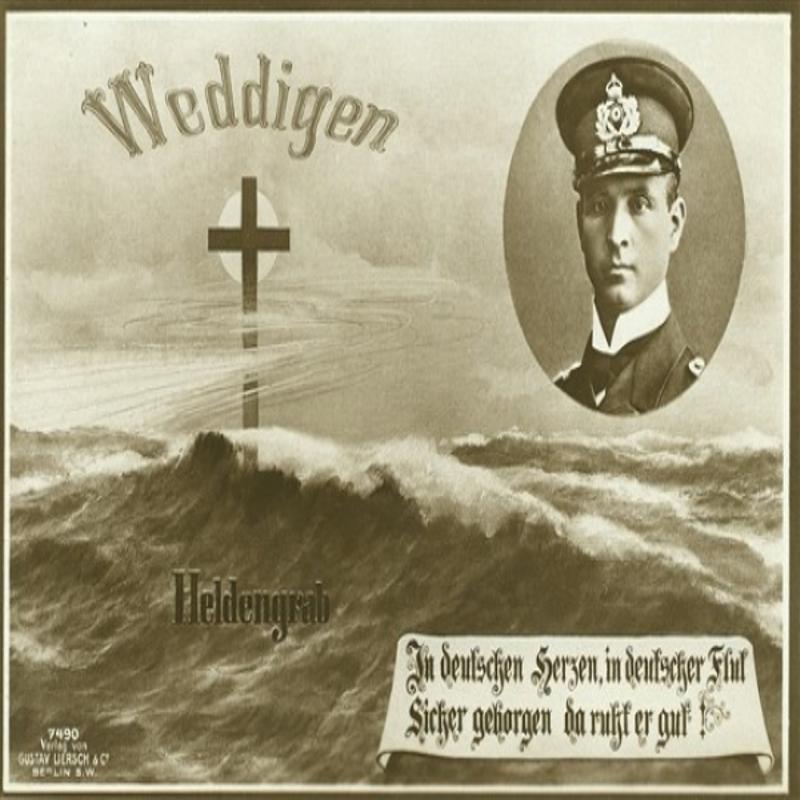

Otto Weddingen returned to Germany a hero, he had exposed the vulnerability of the Royal Navy to underwater warfare and had shown that they did not perhaps rule the waves after all. In a much-publicised ceremony he was awarded the Iron Cross First Class by the Kaiser himself.

Postcards and stamps were issued in his honour and the German press made much of his courage and audacity and the daring of his crew. It was the proudest moment of his life, but he did not live long to enjoy his fame. He was killed on 18 March 1915, when the submarine he was commanding was rammed and sunk by HMS Dreadnought.

The reaction in Britain to the events of 22 September was very different as astonishment soon turned to anger.

The First Sea Lord Winston Churchill came in for particular criticism – how could three Royal Navy warships be sunk like this? Why were they assigned patrol duty in the first place? Why was there no Destroyer escort? And why were they crewed by mostly semi-trained Sea Cadets. The young age of so many of the fatalities, some barely out of school caused outrage and for a time Churchill was referred to as the Murderer of the Innocents. In response, he ordered that all Cruisers be withdrawn from patrol duty, that no Capital ship was to leave port without Destroyer escort, and that in future no Royal Navy warship was to stop to rescue survivors.

The Broad Fourteens disaster was just the first of many humiliations that were to afflict the Royal Navy in the opening years of the war.

The new Battleship Audacious was lost not to enemy action but to a mine off the coast of Ireland on 27 October 1914, the Royal Navy had been unable to force the Dardanelles Straits in March 1915 or protect the East Coast ports of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby from being shelled by enemy warships, and they also failed to seriously impair let alone destroy the German High Seas Fleet at the Battle of Jutland in May 1916.

In the end, the Royal Navy would retain its command of the sea, the U-Boat threat would be tamed, and its blockade of German ports would lead to mass-starvation and break the will of the German people to continue the war. But the submarine menace would never be taken lightly again.

Share this post: