Abraham Lincoln: A Description

Posted on 22nd March 2021

William Howard Russell was an Anglo-Irish journalist for the Times Newspaper in London who is often referred to as the first War Correspondent. Having covered both the Crimean War where he witnessed the Charge of the Light Brigade and described Florence Nightingale as the Lady with the Lamp, and the Indian Mutiny, he was by 1861 in the United States to report on the growing crisis over secession that would soon spiral into civil war.

During his time in Washington, he was to meet President Abraham Lincoln on several occasions, this is his dispatch later published in the Times:

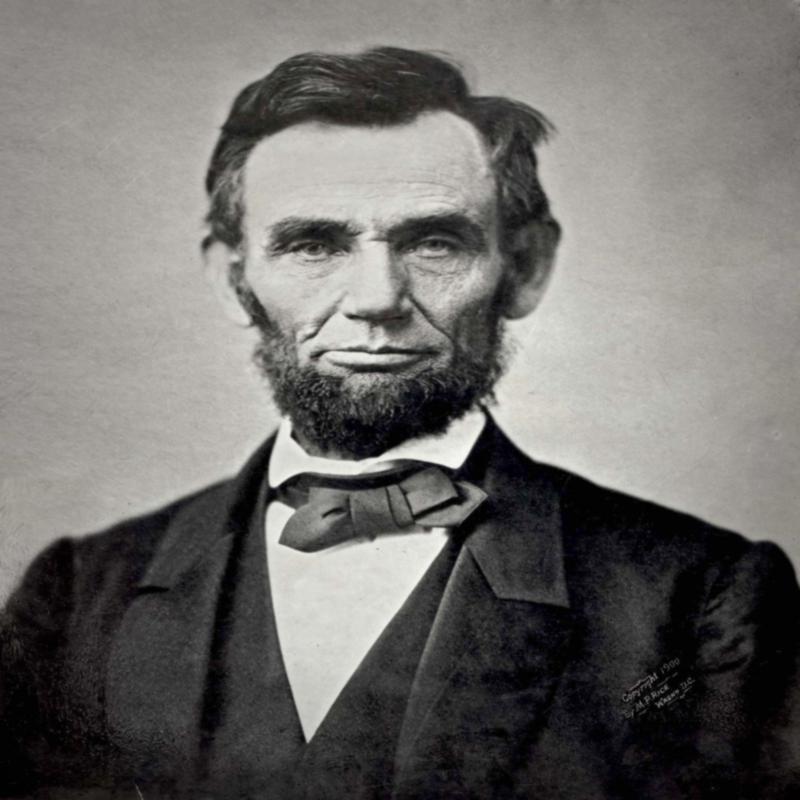

Soon afterwards there entered, with a shambling, loose, irregular, almost unsteady gait, a tall, lank, lean man, considerably over six feet in height, with stooping shoulders, long pendulous arms, terminating in hands of extraordinary dimensions, which, however, were far exceeded in proportion by his feet. He was dressed in an ill-fitting, wrinkled suit of black, which put one in mind of an undertaker’s uniform at a funeral; round his neck a rope of black silk was knotted in a large bulb, with flying ends projecting beyond the collar of his coat; his turned-down shirt-collar disclosed a sinewy muscular yellow neck, and above that, nestling in a great black mass of hair, bristling and compact like a ruff of mourning pins, rose the strange quaint face and head, covered with its thatch of wild, republican hair, of President Lincoln.

The impression produced by the size of his extremities, and by his flapping and wide projecting ears, may be removed by the appearance of kindliness, sagacity, and the awkward bonhomie of his face; the mouth is absolutely prodigious; the lips, straggling and extending almost from one line of black beard to the other, are only kept in order by two deep furrows from the nostril to the chin; the nose itself – a prominent organ – stands out from the face, with an inquiring, anxious air, as though it were sniffing for some good thing in the wind; the eyes dark, full, and deeply set, are penetrating, but full of an expression which almost amounts to tenderness; and above them projects the shaggy brow, running into the small hard frontal space, the development of which can scarcely be estimated accurately, owing to the irregular flocks of thick hair carelessly brushed across it.

One would say that, although the mouth was made to enjoy a joke, it could also utter the severest sentence which the head could dictate, but that Mr. Lincoln would be ever more willing to temper justice with mercy, and to enjoy what he considers the amenities of life, than to take a harsh view of men’s nature and of the world, and to estimate things in an ascetic or puritan spirit.

A person who met Mr. Lincoln in the street would not take him to be what – according to the usages of European society – is called a ‘gentleman;’ and, indeed, since I came to the United States, I have heard more disparaging allusions made by Americans to him on that account than I could have expected among simple republicans, where all should be equals; but, at the same time, it would not be possible for the most indifferent observer to pass him in the street without notice.

In the conversation which occurred before dinner, I was amused to observe the manner in which Mr Lincoln used the anecdotes for which he is famous. Where men bred in courts, accustomed to the world, or versed in diplomacy, would use some subterfuge, or would make a polite speech, or give a shrug of the shoulders as a means of getting out of an embarrassing position, Mr Lincoln raises a laugh by some bold west-country anecdote, and moves off in a cloud of merriment caused by his joke.

Tagged as: Fact File

Share this post: