Agrippina and Messalina: Rivals for Power

Posted on 17th February 2021

Julia Agrippina, known as Agrippina the Younger, was born around AD 9. She was the daughter of Agrippina the Elder and the great-granddaughter of Augustus the Divine. She was the niece and adopted daughter of the Emperor Tiberius, sister of the future Emperor Caligula and the mother of Nero.

She was then a member of the Julio-Claudian clan and as a scion of the Imperial Family was immersed in Court intrigue almost from the day she was born. Her most obvious attributes could be said to have reflected this for she was beautiful, cunning, deceitful, ambitious, domineering and ruthless.

Valeria Messalina, though of noble birth was not so exalted. Despite being a distant cousin of Agrippina and a regular attendant of parties thrown at the Royal Palace she was far removed from the levers of power. This scheming and sharp-tongued woman, at the time little more than a girl, would emerge to become the most powerful person in Rome - or so she thought.

Agrippina’s life was one fraught with danger. As a daughter of the Imperial Family her life was not her own but lay in the hands of her male relatives and what she did, who she met, and where she went was often dictated by the requirements of State policy. As such, a series of politically arranged marriages quickly followed her ascent to womanhood. Even so, her life remained fairly conventional until her brother Gaius ascended to the throne as the Emperor Caligula in AD 37.

Caligula was notoriously fond of his sisters and is believed to have had an incestuous relationship with all of them. He certainly enjoyed watching on as he forced them to have sex with his friends, often in public. Far and away his favourite was his eldest sister, Drusilla. Their public displays of affection for one another were scandalous and there is little doubt that he considered Drusilla to be his de facto wife. Early in his reign however Drusilla died, it was said at his own hands after she revealed to him that she was pregnant with his child.

Typically, Caligula looked around for someone else to blame for his loss and his ire fell on his other sisters who he accused of being jealous of Drusilla. His relationship with them turned sour and when he uncovered a plot against him in which Agrippina in particular was implicated, he had them exiled to the Pontine Islands in the Mediterranean. He then auctioned off all their worldly goods and they were forced to work for a living diving for sponges.

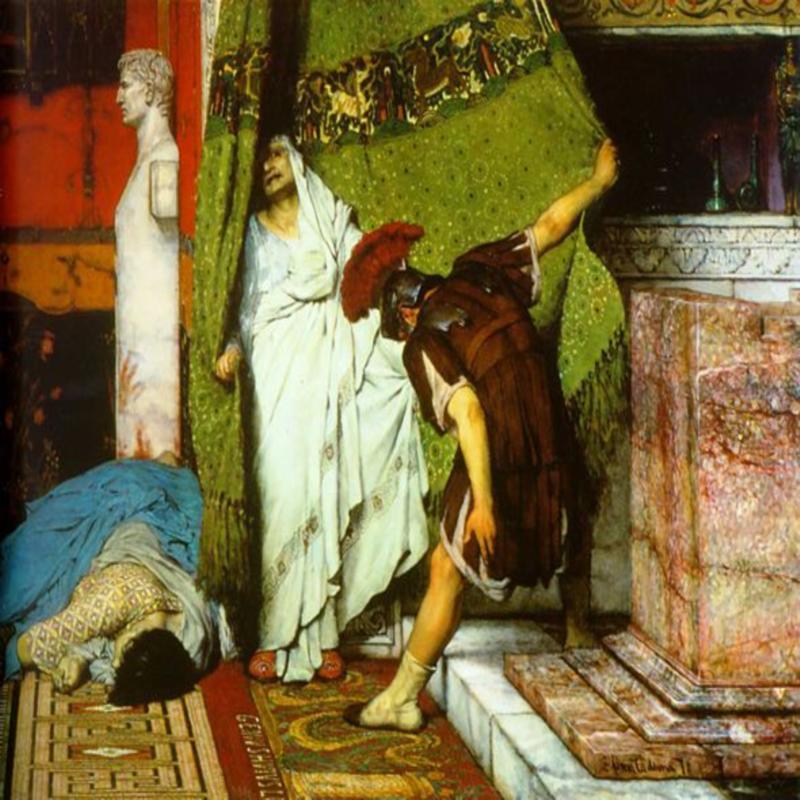

Caligula’s reign as Emperor was to be a short one and thought to be insane, he was murdered on 24 January, AD 41 after less than 4 years in power the victim of a Republican plot. The conspirators had in fact intended to murder the entire Imperial Family and Caligula’s wife and child were indeed killed but they failed to find Agrippina and Livilla. Moreover, his uncle Claudius was discovered was found by the Praetorian Guard cowering behind a curtain in the Imperial Palace.

During his reign Caligula had forced his uncle to marry the 17-year-old Valeria Messalina, 30 years his junior. It was intended as a joke, but Claudius soon became besotted with his beautiful, pale skinned, blue-eyed young wife - but then he was always a slave to his women. She however, with his stammer, bad skin, club foot, and tendency to dribble found him physically repulsive. Even so, she bore him 2 children.

Messalina with her husband putty in her hands soon displayed a side to her character that was arrogant, deceitful and greedy regularly mocking the Emperor behind his back. Everyone at Court appeared able to see this except Claudius himself. In his presence she would be flattering and cloying but this was to get her way. She was determined to rule in her own right and if this meant yielding to her monstrous husband’s sexual demands then so be it.

Upon becoming Emperor, Claudius though he was not known to be particularly fond of either of them facilitated the return of his nieces Agrippina and Livilla.

Agrippina’s ambition had not been dimmed by her exile. Unlike her sister Livilla who returned to her husband and disappeared into obscurity before later being murdered, Agrippina was determined to remain firmly within the Imperial loop. Realising however that as a rival to Messalina her life might be in danger, she for a time maintained a low-profile and stayed away from the Imperial Palace.

In any case, she had other short-term priorities. She had returned to Rome penniless. Desperate for a husband of means she made an immediate a shameless play for the successful General, and future Emperor, Galba. But he was already married and spurned her advances. Agrippina was not a woman used to being turned down, but she was to be further humiliated when she was slapped across the face and given a public dressing down by Galba’s mother-in-law. It was her uncle Claudius who came to her rescue when he ordered Gaius Sallutius Crispus, a wealthy ex-Consul, to divorce his wife and marry Agrippina instead.

In AD 47, Crispus suddenly and mysteriously died. It was rumoured at the time that Agrippina had poisoned him. But they were only rumours, and as his widow she inherited his estates becoming a wealthy woman in her own right.

While Agrippina hurried to feather her own nest and re-establish herself as a prominent member of Roman society, Messalina, with Claudius often away from the city, was busy governing Rome and she ruled with a rod of iron, anyone who dared to oppose her assumption of power or deigned to offend her in any way was harshly dealt with.

In the summer of AD 47, she attended the Secular Games with her young son Britannicus. Also present was Agrippina with her son Lucius, the future Nero. The reception accorded to her by the crowd was far greater than the one that greeted Messalina. It did not go unnoticed, and the two women glared at one another throughout and it was remarked upon by those present how they did not speak to one another, not that Messalina was much known for exchanging pleasantries.

Messalina returned to the Imperial Palace furious at the way the crowd had responded to Agrippina, a woman who was little more than a whore as far as she was concerned. After all she had even had sex with her own brother! If she had not realised that she had a rival, she did now. But Messalina knew that a woman could not rule Rome alone, she needed a man, a weak and easily manipulated one perhaps but someone who would at least serve as the conduit of their rule. So, without her son Agrippina’s ambitions would be thwarted. That night assassins were dispatched to murder Lucius but, as they entered his bedroom and prepared themselves to strike a snake emerged from beneath the bedclothes. It was considered an ill omen and the assassins fled.

Messalina’s behaviour was becoming increasingly erratic. Her infamous competition against the prostitute Scylla to see who could satisfy the most sexual partners became the talk of the city. The fact she won claiming 25 fully paid-up and sexually gratified customers only enhanced her reputation as Lyasca, or the Wolf Girl.

Messalina was described at this time by the historians Tacitus and Suetonius as being lustful, avaricious, cruel, and foul-mouthed. It was said that she frequented brothels most nights, and that she would hide her black hair under a blonde wig and parade naked offering her services for a fee. She made little, if any, attempt to conceal her antics from her husband. She considered him a fool anyway, and he could always be won round to her side with some sweet words and a sexual favour. But she now over-played her hand.

While Claudius was away inspecting public works at Ostia she married her lover, the leading Senator Gaius Silius. She intended him to replace Claudius as Emperor. No one would support her silly deformed husband, she thought. But the rebellion never caught fire and it was easily crushed. She had misread the public mood and had not realised that she was more unpopular than her husband had ever been.

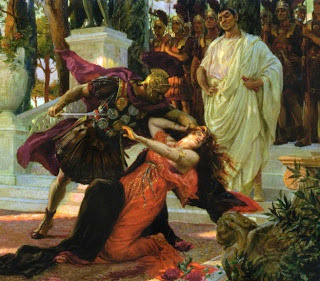

She was placed under house arrest and despite her pleas was not permitted to see the Emperor. As she was writing a letter begging Claudius’s forgiveness, if only for the sake of the children, she received the order that she was to take her own life. She refused to believe it and insisted that if only she could see her husband all could be explained and put right. The Praetorian Guard Officer in charge curtly informed her that if she did not kill herself then his men would do it for her. Messalina began to scream and wail. She shrieked that her husband would never order such a thing and in a flood of tears threatened the Officer with the consequences of his actions. Her mother Lepida now intervened. She had long ago tired of her daughter’s antics and now forthrightly told her: “Your life is done. All that remains is to make it a decent end.” Still Messalina refused to take her own life. As she turned away from her mother in disgust, one of the guards drew his sword and decapitated her.

With Messalina gone, Agrippina at last felt able to assert herself. She determined to marry her uncle and secure the succession for her son.

Following his betrayal by Messalina however, Claudius had vowed never to marry again. So, Agrippina set about seducing him. She would fondle and shower him with kisses in outrageous displays of public affection. Once again putty in the hands of his women Claudius soon succumbed to her advances. Despite an uncle marrying his niece being incestuous and illegal under Roman law, they were married in AD 48.

Agrippina worked tirelessly to persuade Claudius to adopt Lucius as his son and heir. Even though, she had been warned by a soothsayer that should her son ever take the throne he would end by murdering her. To which Agrippina replied: “Then let him kill me, as long as he becomes Emperor.”

But her intention all along was that they should rule in tandem. Claudius, unable to resist his wife’s demands did indeed adopt Lucius, even nominating as his successor over and above his own son, Britannicus. Now freed from the requirement to satisfy her husband’s every whim Agrippina’s domineering personality, her constant efforts to promote the interests of her son and Lucius’s own loathsome personality soon began to alienate Claudius. He once more began to favour his own son who would soon come of age - Agrippina was forced to act.

On the evening of 13 October, AD54, at one of his frequent family banquets which though often long and wearying he insisted all guests attend it was noticed by those present how keenly Agrippina held onto her husband’s every word and how affectionate and attentive she was. She held his hand, she stroked his hair, she whispered sweet words in his ear, and she blew him kisses. She knew how fond Claudius was of mushrooms and she had prepared for him a special treat, a plate of mushrooms soaked in olive oil, but she had also added a few ingredients of her own. Some of the mushrooms had been poisoned and Agrippina had bribed his food taster. The food taster ate one of the good mushrooms before declaring them fit to eat. Claudius, eager to tuck in, did so with relish but before long he became violently ill. Unfortunately for Agrippina he vomited up the noxious content of his stomach. A doctor was sent for, but he too had been bribed. He suggested that the Emperor tickle the back of his throat with a feather to remove any remaining toxins. But the feather used was coated with poison also. Soon Claudius started to convulse and choke, he struggled to breathe, he slumped forward, and he died.

Following the death of her husband, Agrippina wasted no time in having her son Lucius proclaimed Emperor. Endorsed by the Senate the new sixteen-year-old Emperor now changed his name from Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus to Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus.

Agrippina had achieved her ambition and now she was determined to rule alongside her son. Dominated by his mother and guided by his tutor Seneca, Rome’s leading philosopher, and Borrus, the Commander of the Praetorian Guard, for the first few years of his reign Nero showed great promise and he governed with reason and no little good sense. But it wasn’t to last.

Agrippina sought to keep her son on a tight leash. The first coins minted during Nero’s reign show both the Emperor and his mother together except she is in the foreground and he in the background. As far as she was concerned, they were co-rulers and she was the dominant one. Nero however soon came to see his domineering mother as an encumbrance to his own ambitions and both Seneca and Borrus were to support him in his determination to side-line her.

In June, AD 53, before he became Emperor, Nero had married Claudius’s daughter the chaste and noble, Octavia. It had been a political marriage only and Nero rarely saw let alone spoke to his wife. Instead, he had his eyes set on the beautiful, bisexual, vain, and mercurial Poppaea, an exotic dancer of low-birth and even lower-repute. Nero knew that his mother would never accept him divorcing the popular Octavia so behind her back he had his wife banished and soon after secretly murdered.

Nero had begun to act arbitrarily without consulting either his mother or his advisers. The more he did so the more Agrippina bullied and nagged him, but she was losing control over her son. Beginning to fear for her own safety Agrippina began to shower her affections on her stepson Britannicus. Nero was aware of the relationship being developed. In February, AD 56, Britannicus collapsed during a banquet at the Imperial Palace. Nero declared that it was little more than an epileptic fit and had the boy carried away. But he had been poisoned and was already dead. Even as the festivities continued the body was being burned.

Nero’s relationship with his mother continued to worsen however, and in AD 57, he banished her from the Imperial Palace altogether forcing her to live on the Island of Misenum.

They would still meet from time-to-time, but Agrippina now had to be invited to visit or make a formal request to see her son. Indeed, Nero took great pleasure in sending people to harangue and harass his mother, to stand outside her home and shout verbal abuse late into the night. Agrippina, whenever she got the opportunity never failed to remind Nero that he was only Emperor because of her.

Nero was by now heartily sick of his mother’s constant nagging and meddling in his affairs. Not only that, but she also showed him no respect and continued to publicly chastise him. She had to go, but how? He could not be seen to order the execution of his own mother and poisoning her was too obvious. So, he came up with an ingenious plan. He had his engineers design a collapsible boat – it wasn’t his first ingenious plan he had earlier devised a mechanical lead ceiling that would crush her as she slept but this hadn’t worked. So, he would invite his mother to dinner. At the end of the night, he would present the boat to her as a gift. On the return journey to Misenum the bottom of the boat would fall out and she would drown. It was indicative of Nero that simple murder wasn’t enough it had to have a theatrical flourish to it, but it had a fatal flaw. His mother had been forced to work during her exile diving for sponges and she was a first-rate swimmer.

The boat did indeed collapse as it had been designed to do and began to sink but Agrippina did not panic. As the boat began to founder, she dived overboard with her friend Acceronia Polla whom she told to say she was Agrippina then she would be rescued by guards on the accompanying boats instead shouting, “I’m Agrippina, save me!” she was grabbed by the wrists and bludgeoned to death. In the meantime, Agrippina swam with vigour towards the shore. The tides were against her, but she managed to stay afloat long enough for some local fishermen to come to her aid. She was exhausted, bedraggled, and frightened, but she had survived.

Nero, upon hearing that his mother was still alive went into a rage. Now there would be no pretence, his mother would die and that would be an end to it. He ordered the Commander of the Praetorian Guard to go to Misenum and finish her off, but he refused. He would not commit matricide on the Emperor’s behalf especially as she was the daughter of their hero Germanicus. But he soon found a willing accomplice.

Agrippina was discovered lying in her bed recovering from her ordeal. At first, she chastised the assassins for disturbing her but she quickly realised why they were there. She insisted that no son would order the murder of his own mother and that they had been given incorrect orders and would pay dearly for their mistake if they did not leave. Instead, they drew their swords and made to finish her off. Realising it was the end Agrippina threw off the bedclothes and pointing to her womb said - “Strike here!”

Upon hearing the news of his mother’s death, a delighted Nero remarked:

“At last, I am free to live like a man.”

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: