Amelia Earhart: The Lady Lindy

Posted on 13th April 2021

For almost a decade she was one of the most celebrated people in the world as famous as any movie star and more popular than most. Her exploits were to make headlines around the globe, she was an icon of the age in which she lived, and her disappearance remains one of history’s most enduring mysteries.

Amelia Mary Earhart was born on 24 July 1897, in the small town of Atchison in rural Kansas. Her parents were affluent, upwardly mobile and socially liberal and they permitted Amelia and her younger sister Grace to run free with both enjoying the outdoors earning a reputation as tomboys and for sometimes making a nuisance of themselves.

Not all was quite as it seemed within the Earhart household for her father, Samuel, unknown to his children was an alcoholic and family fortunes fluctuated as a result; and even though they were never exactly poor much of the family’s money was put into trusts for the children to keep it out of their father’s hands. It was a wise decision when in 1914 her father’s condition had worsened to the point where he was forced to retire from his high-profile job with the Rock Island Railways.

Samuel fought hard against his addiction and by the following year had recovered sufficiently to find employment with the Great Northern Railway in St Paul’s, Minnesota, but only as a lowly clerk, and it wasn’t long before the old demons re-emerged, and he lost that job as well.

Amelia’s mother Amy, facing the prospect of another expensive move and with her marriage stretched to breaking point sent her daughters to live with relatives in Chicago.

The declining fortunes of the Earhart family and the increasingly itinerant nature of their existence seemed to suit Amelia’s restless nature and equally butterfly mind. She was aspirational and kept a scrapbook of successful women especially those who had succeeded in professions considered the domain of men only but what career to pursue remained a mystery. The parental guidance she perhaps needed to succeed was missing but it gave free vent to her imagination.

Her school days however, had not been happy and she confessed in her diary that she had been a loner with a high opinion of herself who did not make friends easily and in the autumn of 1916, she left Hyde Park School in Chicago at a bit of a loose end.

After briefly attending college, she travelled to Canada to visit her sister and whilst in Toronto she came into contact with repatriated soldiers who had been wounded in the Great War and immediately enrolled as a nurse. Following the end of the war she decided that she wanted to continue her medical studies and enrolled at Columbia University in New York but quit soon after. Once again at a loose end in 1920, she travelled to California to live with her parents who had since been reconciled.

She had not up to this point in her life expressed any interest in flying at all but this was to change on 28 December 1920, when she attended an aerobatics display with her father and offered the opportunity to take a short flight she was overwhelmed by the experience later saying that: “By the time I got to two or three hundred feet I just knew I had to fly.”

Over the next few months, she worked in a variety of jobs including as a telephonist, stenographer and even as a truck driver to raise the $1,000 dollars required to take flying lessons. Her teacher was to be another woman, Anita Snook, and on 3 January 1921, in a Curtiss JN-4, also known as a Canuck, she took the controls of an aeroplane for the first time and on 13 May 1923, she became only the sixteenth woman in the world to be issued with a pilot’s licence.

Despite its extensive use during the Great War, flight was still in its infancy and considered something of a novelty but it also represented the latest unknown to be conquered in the post-war brave new world.

On 21 May 1927, Charles Lindbergh in his bi-plane the Spirit of St Louis landed at Le Bourget Airfield near Paris making him the first man to fly solo non-stop across the Atlantic. The achievement made him a national hero and the clamour soon grew to find the first woman to do likewise.

Despite Lindbergh’s success it remained a perilous journey and, in the months, preceding his flight numerous highly regarded aviators had lost their lives in the attempt and so finding a woman, many of whom were mothers, among the few female aviators there were willing to take the risk was proving difficult. It was made even more so by the fact that the man in charge of finding a woman flier, the publicist George P Putnam, was determined that whoever it was should exude the right image – young, attractive, as wholesome as apple pie and preferably single.

Earhart had expressed little interest in being that woman until she received a phone call from Captain Hilton H Railey who simply asked her: “Would you like to fly the Atlantic?” The call had been unsolicited but perhaps it should not have been unexpected, they were bound to get to her eventually. She agreed, but not without reservations.

The plane itself was to be flown by Wilmer Stultz and his co-pilot Louis Gordon. The only woman aboard, Amelia Earhart, was given the responsibility for updating the flight log in an attempt to provide her presence with some credibility but in reality, she was little more than excess baggage. It didn’t matter, the fact that she was on the plane at all was to make her a global superstar.

Flying a Fokker Trimotor on 17 June 1928, they took off from Trepassey Harbour, Newfoundland. The flight itself took 20 hours and 40 minutes and was largely untroubled but nonetheless when they landed at Burry Park in Wales it was as heroes but most of the attention fell upon Amelia. This was despite the fact that she had at no time taken the controls of the plane and indeed, most of the flight was carried out using instruments that she did not understand or know how to operate.

The much-publicised flight made headlines around the world and despite being little more than a passenger who did odd jobs and poured the coffee she remained the first woman to fly non-stop across the Atlantic and overnight became one of the most famous people on the planet and travelling around Britain attending civic receptions laid on in her honour she was mobbed wherever she went.

On their return to America the flyers were greeted with a ticker-tape parade through the streets of New York and received in the White House by President Calvin Coolidge.

Stultz and Gordon were soon to be forgotten and returned to obscurity but not Amelia – the press had found a new hero and America a new Golden Girl. The plaudits came thick and fast as she was dubbed the Queen of the Air and because of her remarkable resemblance to Charles Lindbergh nicknamed The Lady Lindy.

George Putnam was quick to exploit Amelia’s new-found fame for all it was worth as she embarked upon an exhausting lecture tour, authored a book, and endorsed numerous products which included luggage, cigarettes and a range of ladies’ fashions which for a woman more used to wearing dungarees and boiler suits did not come naturally.

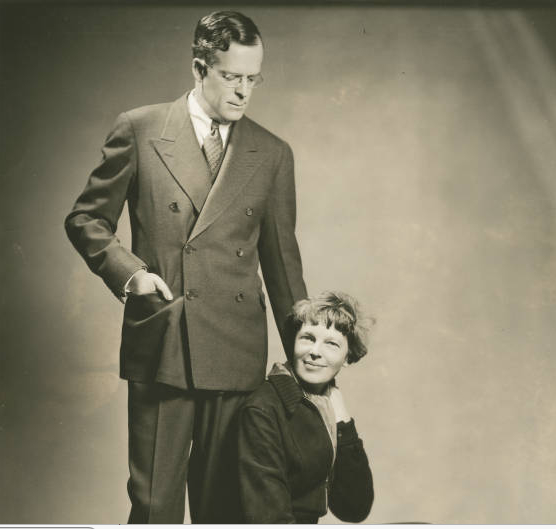

It wasn’t necessarily a union borne of bonds of mutual affection; indeed Putnam had proposed time and again before Amelia finally consented, but they were spending so much time together and he had become such a big part of her live that love aside in every other respect marriage made sense.

Putnam was by now almost entirely devoted to the promotion and marketing of his new wife, and he did a remarkable job turning the tom-boyish, initially camera shy and sometimes visibly uncomfortable Amelia into one of the first female celebrities loved by the camera and at ease in public to the very great surprise of Amelia herself.

However, her fame remained her flying and on 20 May 1932, she took off from Harbour Grace in Newfoundland in a single-engine Lockheed Vega, a rugged and durable little plane with minimal instrumentation which suited her style of flying on the greatest adventure of her life so far – she would emulate the achievement of Charles Lindbergh and fly non-stop solo across the Atlantic Ocean. Whatever her merits as a pilot no one could doubt Amelia Earhart’s determination and courage.

IIt was not an easy journey, and she was buffeted by strong cross-winds throughout which in the already freezing temperatures tested the limits of her physical endurance to their limits. Her powers of concentration also had to remain intense as the instrumentation aboard the plane, which she was loath to use in any case, was so primitive.

The grey featureless sky was difficult to distinguish from the equally grey featureless ocean and even if she were to survive a crash and successfully ditch her plane into the sea her hopes of rescue were almost non-existent.

After an uncomfortable journey that lasted 14 hours and 56 minutes, she landed in a field in Culmore, Northern Ireland. The question posed by the farmer who greeted her – have you come far? Provoked a wry glance, a chuckle, her trademark but now rarely seen gap-toothed smile and simple answer – from America.

For her achievement Amelia was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross by the United States Congress and further honours and awards flooded in from around the world. Just as important for Amelia her fame provided the opportunity for her voice to be heard at a time when the views of women were largely ignored.

Though she was careful not to become too closely associated with any political party she was known to be a supporter of President Roosevelt’s New Deal and became a close friend of his wife Eleanor and campaigned alongside her on several issues relating to greater female equality.

Despite her other activities the pressure remained on Amelia to continue to perform ever greater stunts of aeronautical derring-do and on 11 January 1935, she became the first person to fly solo from Hawaii to California. The route taken had previously been that of the Dole Air Race which had been put on hold since 1927 when 8 out of the 11 competitors had crashed resulting in ten deaths. Amelia’s flight was relatively trouble free but yet again she had succeeded where so many others had failed. Later that same year she set another record when she flew solo from New York to Mexico City.

She still failed to impress in competition however, coming in only a distant fifth in the Bendix Trophy Air Race.

This flaxen-haired, fresh-faced, daring and brave young woman with the twinkle in her eye who exuded self-confidence and pushed the boundaries as if nothing seemed beyond her – just like America itself – remained the nation’s golden girl but people were becoming a little bored. Her exploits continued to make the headlines but they no longer were the page turners of before.

Amelia’s waning popularity was of particular concern to George Putnam who had worked so hard to maintain her high-profile but in truth she had little left to prove. She had been the first woman to fly across the Atlantic and then the first woman to do so solo, she had set records and won numerous awards, but she still had one ambition remaining – to circumnavigate the globe.

Amelia loved flying but whether she felt under pressure to embark on yet another perilous journey at a time when flying was becoming more commonplace and its novelty value was wearing thin is not entirely clear. But to be the first woman to fly around the world the long way would certainly trump all her previous achievements. Yet again the organisation of the trip and the publicity surrounding it lay in the hands of Amelia’s husband.

Fearing that it might be treated as merely yet another record attempt Putnam was keen to promote it as also being about important scientific research and so the project was largely funded by a university but there was in truth little plan to do any. It did mean however that the plane would be overloaded with surplus equipment that would never be used.

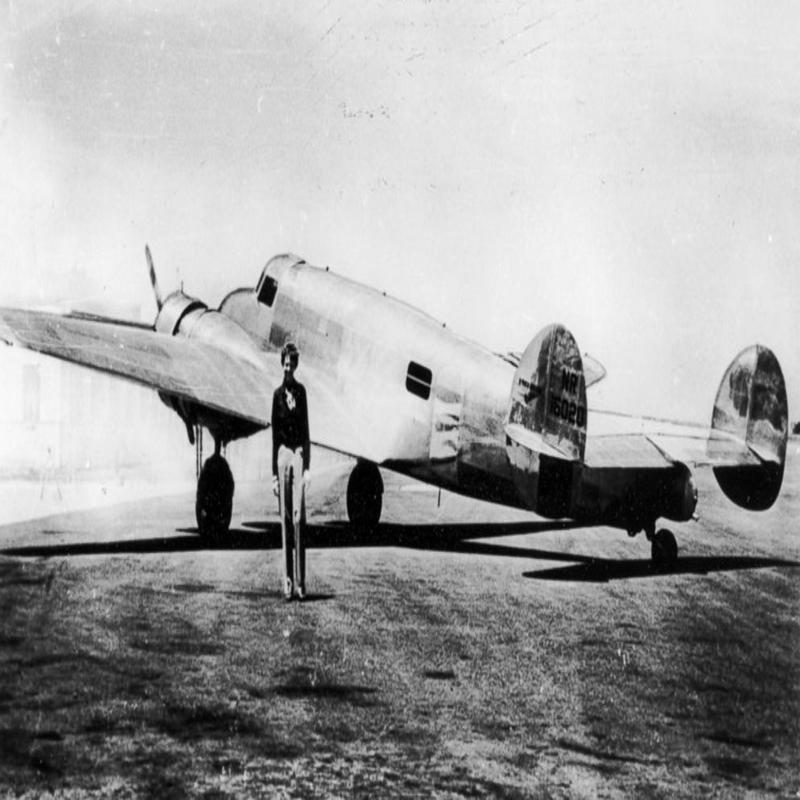

In July 1936, work began on the construction of a twin-engine Lockheed Electra 10E monoplane that was specifically adapted to carry an enlarged fuel tank. That same month Amelia publicly announced her intention to circumnavigate the globe.

Putnam who was busy promoting the flight had hoped it would be another solo triumph for his wife but the complexities of it made this untenable and her co-pilot for the record-breaking attempt would be the experienced navigator Fred Noonan.

Frederick Joseph Noonan was a tough 44-year-old from Illinois who had previously served as a Sea Captain and considered himself first and foremost a mariner but who for the past two years had been working for Pan American mapping their China Clipper routes across the Pacific Ocean.

Despite his preference for the sea his skills as a pilot were widely acknowledged and his navigational abilities considered second-to-none and unlike Amelia he was experienced with the latest up-to-date navigational instruments that she neither trusted nor could fully come to grips with. But his hard-living persona and reputation as a heavy drinker worried some. Indeed, it was rumoured that he was an alcoholic though there seems to be little evidence for this.

After some delay following an earlier attempt in March that had to be abandoned when Amelia crash-landed badly damaging the plane the pair took off from Miami, Florida on 1 June 1937 for their momentous 29,000-mile flight around the world, and the press were there in great numbers to witness it.

After stops in South America and on the Indian sub-Continent by late June they had arrived at Lae in New Guinea. The flight had been relatively incident free and the press which had followed intently every step of the journey had little to report.

By now Earhart and Noonan had completed most of their journey and they had less than 7,000 miles to go but it was the most hazardous leg of the flight across the Pacific Ocean, and they knew it. Their destination was to be Howland Island, a tiny strip of land just 6,500 feet long and 1,650 feet wide some 2,566 miles away – a tiny pinprick in a vast ocean.

The United States Coastguard vessel Itasca was to be stationed off Howland Island to help guide them in and other ships in the vicinity had promised to keep their lights on to act as markers.

They departed Lae on 2 July, but it wasn’t a particularly clean take-off and despite Amelia’s attempt to strip the plane of any unnecessary baggage to allow for more fuel it still appeared heavy and overloaded. It took some considerable time to gain altitude and film footage taken at the time also seem to indicate that the plane may have lost part of its antennae though none was later recovered from the field.

The weather was fine that day though there was some worrying low cloud cover but if communications were maintained few problems were anticipated. As the Electra began to close in on Howland Island the Itasca began to receive clear messages from Amelia but she complained that she could not hear them. At 07.42 she radioed:

“We must be on you, but cannot see you – but gas is running low – have been unable to reach you by radio. We are flying at 1,000 feet.”

At 07.58 she again signalled that she could not hear them and requested that they send more voice transmissions. Her signal was loud and clear however indicating that she must be nearby, but they couldn’t send voice signals on the frequency she was using so they tried Morse code. Amelia replied that she had received the message but couldn’t make out their direction.

The Itasca released smoke in an attempt to help guide them in, but the likelihood is that they were unable to see it because of the low-lying cloud. At 08.43 the Itasca received what would prove to be their last transmission:

“We are on the line 157 337. We will repeat this message. We will repeat this on 6210 kilocycles. We are running on a line north and south. Wait.”

A garbled message then followed.

She was never heard of again; America’s golden girl Amelia Earhart and her navigator Fred Noonan had simply disappeared.

No one knew exactly where to look for them because their last position had never been positively identified. However, signals were continuing to be received from the Electra, or so it seemed, though they were garbled and unintelligible. It was suggested that they might be emanating from Gardner Island, also known as Nikamaroro, a small coral atoll 3.5 miles long and 1.2 miles wide that had previously been occupied by the British but had long since been abandoned.

The biggest air and sea search operation in American history was launched to find the missing pilots as the world looked on gripped by events. The search concentrated on the areas around Gardner Island and her destination Howland Island some 400 miles south-east of it, but it was a vast area of ocean dotted with tiny and almost invisible to the naked eye islands and strips of land. Despite their best efforts no trace whatsoever of the plane was found and on 19 July the search was called off.

George Putnam was angry that the search had been abandoned so quickly and remained convinced that Amelia could have landed the plane safely and that she and Noonan were still alive perhaps stranded on one of the many tiny atolls. He chartered private ships and planes to continue the search, but it was to prove no more successful than before.

On 5 January 1939, Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan were declared officially dead.

The mystery surrounding Amelia Earhart and Frederick Noonan’s disappearance continues to intrigue to this day and conspiracy theories abound. It has been suggested that she was in fact on a spying mission and had been captured and later executed by the Japanese; or that tired of all the fame and constant attention she had faked her own death returning to New York where she worked as an investment banker. The most enduring theory however is that she had either landed her plane or managed to wade ashore onto Gardner Island where she and Noonan survived for some time before expiring either of exposure or dehydration.

A June 2010, expedition to Gardner Island claimed to have found various artefacts including bottles, strips of clothing and cosmetic items that appeared to date from the 1930’s. There was also evidence that campfires had been made and contraptions designed to capture rainwater constructed. The discovery was given added credence by the fact a a pilot had reported during the original search that he had seen signs of habitation on Gardner Island but that despite flying repeatedly over it he could see no people and no attempt had been made to signal him.

Despite this the evidence found was vague and inconclusive and none of it could be tied specifically to either Earhart or Noonan. Neither was any plane wreckage or skeletal remains found. Even if they had managed to scramble ashore uninjured with no shelter, no water, and only the fish they could catch to eat they could not possibly have survived more than a few weeks.

The failure of the many expeditions organised since Amelia’s disappearance to find any convincing evidence of her fate means that the likelihood remains that the plane simply ran out of fuel and crashed into the sea with both she and Noonan either dying on impact or subsequently drowning. But the reason for this happening is almost as controversial as their disappearance itself. Was it because the plane was overloaded? Was it carrying enough fuel? Was it because Amelia was an old-time flyer who did not understand or like to use the latest technology and was unwilling to adapt? Was it because Fred Noonan’s heavy drinking had impaired his judgement? Or was it simply because the entire expedition had been poorly organised from the outset? These are all probably questions we will never have answered.

Amelia however wasn’t naive, and she fully understood the hazardous nature of the ventures she embarked upon, and the life she had chosen for herself, but she viewed every achievement as an advance not just for her but for all women.

When a man fails it is a personal setback when a woman fails it is a reverse for the entire gender. Every failure by a woman must then serve as a challenge for other women to take up the mantle and succeed.

Amelia Earhart succeeded many times and failed only once but once was enough.

Share this post: