Amritsar Massacre

Posted on 16th July 2021

On 22 June, 1897, as Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee procession wound its way slowly through the streets of London to Buckingham Palace the many thousands of people who lined its route were enthralled at the sight of the Empire in the heart of the capital city; and of particular fascination to them were the gaily dressed Sikh and Gurkha troops along with the many extravagantly bejewelled Rajahs and Nawabs.

India had long been the ‘Jewel in the Crown’ of the British Empire and as long as it remained in her possession then the sun would never set upon it – all it seemed was well.

After all, in the Great War more than 1,500,000 Indians had volunteered to fight for the Mother Country and some 800,000 shipped overseas did so. They fought in the Middle East, in Africa, and in the trenches of the Western Front. Of these 12 were awarded the Victoria Cross, 47,476 were killed in the service of the Empire and 65,000 wounded.

It was a display of loyalty to the British Raj that shocked many in India itself because for many years it had been a seething cauldron of resentment. But this support had never been unconditional, a quid pro quo was expected on the part of the British and this meant nothing less than self-Government. When this was not forthcoming resentment quickly turned to violence.

The British tried to placate the ire of many Indians by establishing a Parliament, but its scope was so limited that any effective role was all but nullified. It remained the case that despite their loyalty to the Crown during the war the Indians were distrusted and were believed unfit to govern themselves.

The Defence of India Act passed in 1915 and supposedly an emergency wartime measure which allowed for the arrest and internment of those accused of sedition without charge, remained in place while press censorship and the trial of suspects before specially convened secret tribunals that were expected to be abolished following the wars conclusion were merely reinforced by the passage of the Rowlatt Act in 1919.

The British political establishment in Westminster would not countenance loosening their grip on India and were determined that the levers of power would remain firmly in their hands.

India had not been immune from hardship during the war, the British had raised taxes to almost punitive levels and the disruption in trade had led to severe shortages, increased poverty, and in some places even starvation. The flu pandemic that swept the Continent at the war’s end just added to the overall misery.

Dissent was growing at the incapability or unwillingness on the part of the British to tackle issues that were affecting Indians daily and the more they tried to rule with a rod of iron instead the greater the dissent.

The Indian National Congress, an organisation dominated by English educated upper-caste Hindus was coming increasingly under the influence of a lawyer and holy man Mohindas Gandhi, known as the Mahatma, and his Satyagraha Movement which advocated non-violent mass non-cooperation. It was gaining widespread support for the first time the Congress began to act in unison on a national level as protests against the Rowlatt Act were organised the length and breadth of the country.

In the Punjab, where tensions were running high, a mass-demonstration had been organised against the arrest of two nationalist leaders Satya Pal and Saifuddin Kitchlew, members of Gandhi's Satyagraha Movement. It was to take place at the Jalianwala Bagh, a walled garden near the Golden Temple and over 5,000 people were expected to attend in what was a confined space with few points of egress.

They were to be noisy, fervent and angry but for the most part were unarmed and it was intended to be a peaceful, non-violent protest in line with the movement’s ethos.

But in the days prior to the demonstration there had, been sporadic outbreaks of violence. Small crowds of protesters had gathered outside the Lieutenant-Governor's Residence and missiles had been thrown, the crowd fired upon and people. In retaliation several buildings had been set alight while on 9 April, a British woman, Marcella Sherwood, who supervised the local Mission Schools, was attacked and severely beaten as she cycled through the streets of Amritsar.

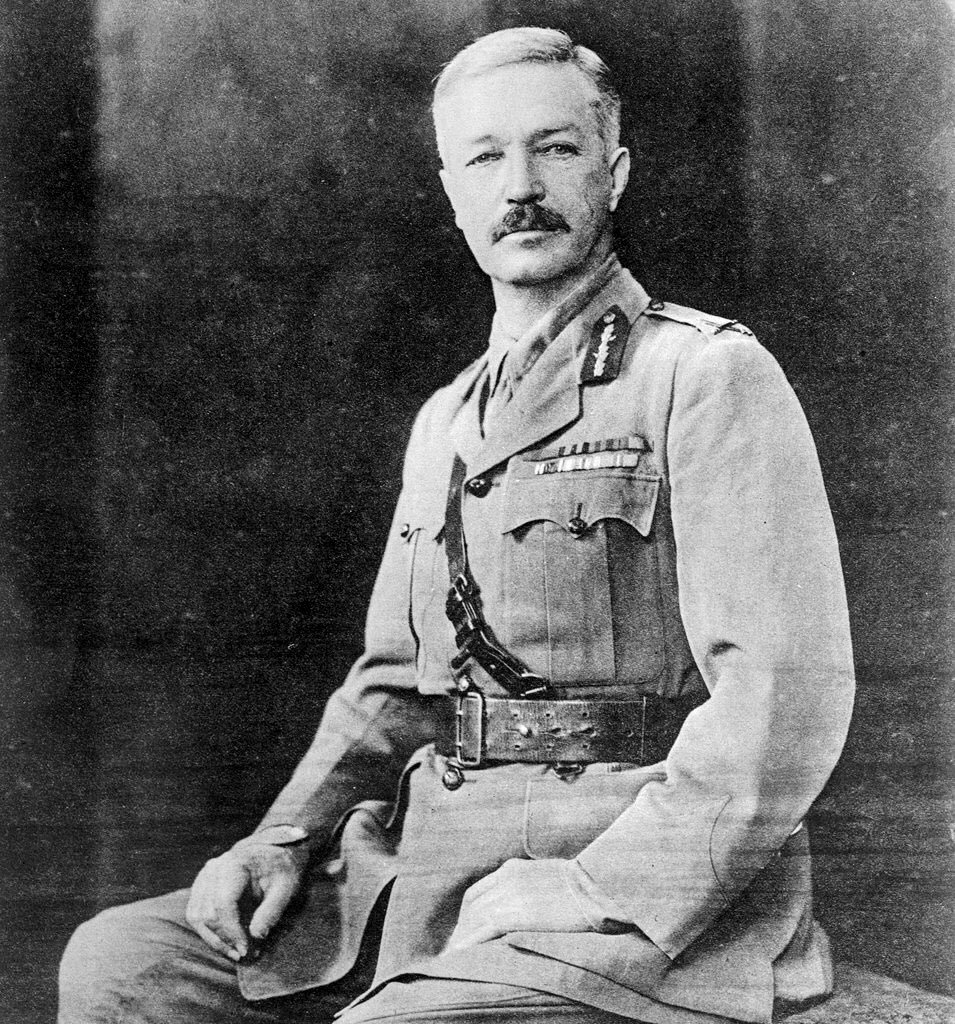

This act of gross indecency as he saw it particularly outraged the local Military Commander General Sir Reginald Dyer, an unsympathetic man who had little time for the ‘Browns’ as he called them despite having been an Officer in the Indian Army for over 30 years.

Though things had been relatively quiet in Amritsar itself in the run-up to the planned Jalianwala Bagh the situation in the Punjab as a whole was very different, telegraph lines had been cut, railways sabotaged, Government buildings set alight, and some 8 Europeans had been murdered. There was a sense of revolution in the air and nerves were strained.

Dyer firmly believed that the demonstration arranged for the Jalianwala Bagh was part of a deliberate plot to overthrow British rule in India and he was determined to stamp out any dissent within his jurisdiction. So on the morning of the intended rally, he marched 90 men, mostly Gurkha troops, and two armoured cars to police what he considered nothing more than a howling mob.

As the crowd were whipped up into a frenzy of anger by speaker after speaker, Dyer fumed at the abuse being hurled in his direction and the wild gesticulations of the protesters. He ordered the troops to open fire disperse the crowd. He had issued no warning and his troops misunderstood this to mean in the air; but he soon corrected them and ordered them to lower their sights and fire into the thickest part of the crowd. They obeyed without question; Gurkhas are good soldiers.

Panic quickly ensued as 5,000 desperate and frightened people scrambled to escape rushing for the few available exits. There was little cover in the garden, nowhere to hide or seek shelter and dozens were to die as they leapt into a well to escape the bullets. Many others were trampled to death in the stampede, but most were to die of bullet wounds as the firing intense and relentless continued for what seemed an eternity. It only ceased when the ammunition ran out. Dyer was later to express his regret that he had not made provision for more.

Within what was in fact just a few short minutes 379 people had been killed and a further 1100 wounded. At least, that was the official figure.

In the immediate aftermath of the massacre General Dyer was widely praised for his quick and decisive action. He had, it was felt, nipped a Second Indian Mutiny in the bud. The Lieutenant-Governor of Punjab, Michael O'Dwyer, sent him a telegram: "Your action is correct and the Lieutenant-Governor approves."

There was outrage in India at what had been by any definition a massacre and a Commission of Inquiry was hastily formed to get to the full facts of the case. It established that General Dyer had been fully aware that a demonstration was due to take place but had done nothing to raise issues of safety or tried to prevent it on grounds of security. Neither had he spoken to the organisers beforehand.

When questioned about the events of the day he remained wholly unapologetic. He had neither tried to disperse the crowd by other means or issued a warning of the consequences should they refuse to do so because they were unworthy of such consideration, and he would merely have been laughed at and made to look a fool.

The Commission wanted to know if the two armoured cars he had taken along not been unable to enter the Jalianwala Bagh because the entrances were too narrow, would he have used their machine guns on the crowd? Dyer answered - "Yes, without question."

When asked why he made no effort to tend to the wounded he replied: "It was not my job. The hospitals were open."

They then wanted to know why he had not ordered the firing to cease when it became apparent that the crowd were trying to flee? "It was my duty to continue firing," he said.

The Commission was critical of Dyer's actions but concluded that there should be no penal sanction. But the Commission’s findings did nothing to placate the anger sweeping India and so on 20 March 1920, he was relieved of his command and forced to retire.

In Britain, General Dyer was first thought to be the man who had saved India for the Empire but as the details of the actual events of Amritsar became more known the feeling turned from one of relief to one of shock. Winston Churchill described it as monstrous and was censured in the House of Commons for having done so. Whilst the former Prime Minister Herbert Asquith said it was one of the worst outrages in the whole of our history.

Having been forced to resign his Commission, General Dyer returned to England where he was presented with a cheque for £26,000, the proceeds of a public collection made on his behalf. Not long after he suffered a stroke and was to remain incapacitated until his death in 1927. The fall-out from the Amritsar Massacre continued, however.

On 13 March 1940, the former Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab, Sir Michael O'Dwyer who had appeared to endorse Dyer’s actions at Amritsar was shot and killed in Caxton Hall, London by an Indian nationalist, Udam Singh who was was later hanged in Pentonville Prison for murder.

The terrible events at Amritsar were to undermine British legitimacy in India while the campaigns of strikes, sit-ins and non-cooperation instigated by Mahatma Gandhi reached unprecedented levels of support until the demand for independence became deafening.

The Amritsar Massacre marked as the beginning of the end of the British Raj in India.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: