Ancient Egyptian Religion

Posted on 14th April 2021

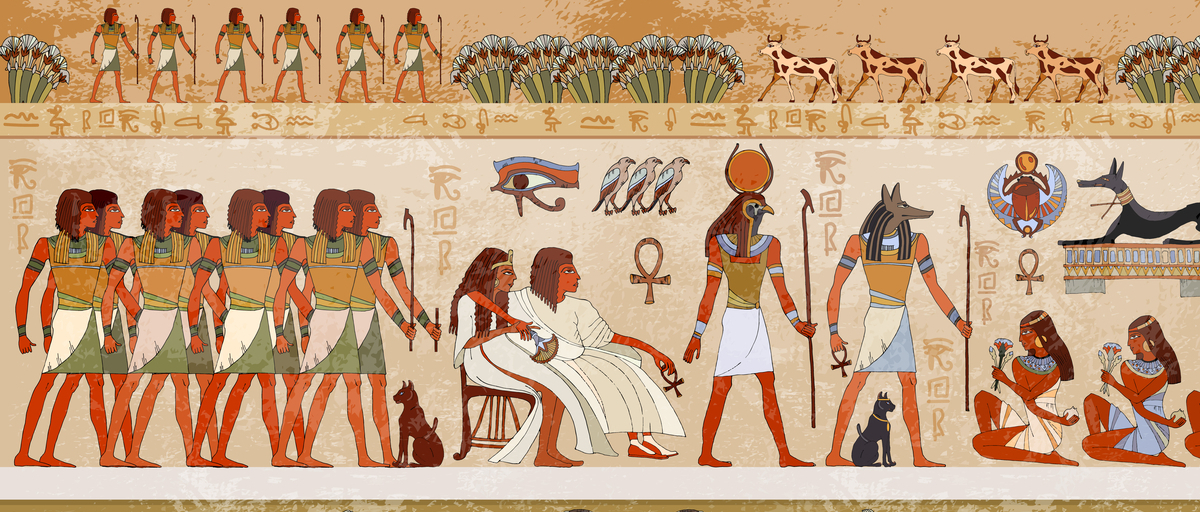

The Ancient Egyptians held a complex system of polytheistic beliefs which played an important part in the daily life of the people. A multitude of Gods controlled all the forces and elements of nature, and Egyptian religious practice was designed to provide for these Gods and by doing so placate them.

They had had a fixed concept of the Universe known as Maat or Order, which they believed had to be maintained to stave off catastrophe and so the cycle of nature was regulated by frequent offerings and a series of rituals with the success or otherwise of these religious devotions determined by the normal passage of the seasons. Even natural phenomenon with unfortunate consequences such as the flooding of the Nile, which was expected each year were prayed for, it being considered an ill-omen should they not occur – tragedy was to be endured if by doing so it maintained the balance of the Universe.

Religious practice centred upon the person of the Pharaoh, the living embodiment of the Gods in human form was expected to display all the frailties that afflicted mortal man – illness, disease, vice, temper, lust, cruelty and death - and so it should be as the intermediary of the Gods, the conduit between the human world and the afterlife.

It was the Pharaoh who was charged with guaranteeing that the Gods were sustained sufficiently to maintain order in the Universe, and the Egyptian State ensured that no expense was spared in the performance of rituals and the building of Temples. Religious worship therefore was not the responsibility of the individual alone, it was State organised, State controlled and run by a ubiquitous priesthood.

The people prayed to order, but it was in the practice of magic rather than religious devotion that they sought spiritual succour in their everyday life and the number of God’s in Ancient Egypt were myriad with national Gods, local Gods, and even individual and family Gods.

Every deceased Pharaoh was worshiped as a God regardless of how hated he had been in life or how vilified he was in death. But a commoner could just as well achieve similar status:

Imhotep, the famous physician, architect, Chancellor of the Pharaoh Djoser and High Priest of the Sun God Ra despite only being the son of a merchant was deified following his death.

There was no one all-powerful and unifying deity such as was common in other ancient societies. One God or another might rise to prominence during a specific era but there was no equivalent to a Zeus, Jupiter or Odin. Among the most prominent were the Sun God Ra, the Falcon God Horus, and the Mother Goddess Isis.

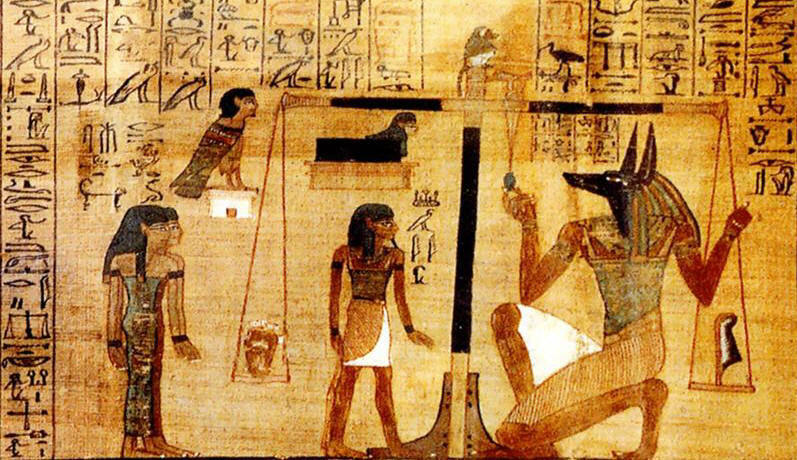

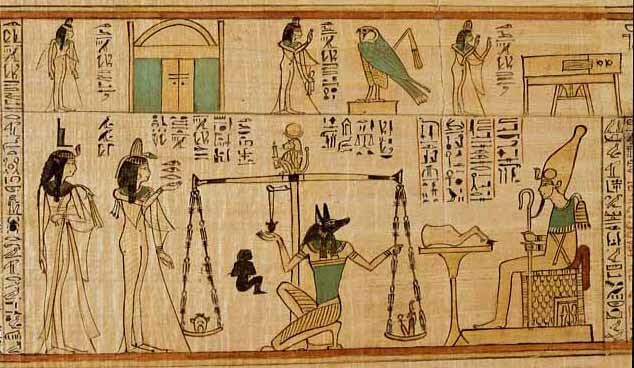

Egyptian art depicted the Gods in earthly form with the most famous being that of the funerary God Anubis, often portrayed as a jackal. The jackal being a scavenger that feeds on the remains of the dead offers were made for his favour to ensure the preservation of the recently deceased and often diseased body. Likewise, Anubis was always portrayed in the colour of mummified flesh and the fertile soil of the Nile Delta that the Egyptians associated with eternal resurrection.

Many animals were also considered sacred. The favoured domestic pet was the cat which was not just pampered but worshiped as the living symbol of the Goddess Bast and to harm a cat could lead to harsh punishment, even death. Dogs were also worshiped as hunters, though they did not have the mystique or cunning of the cat, but representative of the God Anubis were admired for their courage and devotion.

These symbolic animals like the Falcon God Horus were represented in art and statues as iconic statements of the Divine. Even a bird as common in Egypt as the Ibis was still believed to be the Sacred Bird of Troth while scavenger birds such as the vulture were thought to be the deities Nekhbet and Mut come to earth.

Egyptian society, like all societies had its myths.

For example, it was believed that Egypt had been created as a dry land in an ocean of chaos and it was the Sun God Aten who formed the elements that created the Maat, the emergence of the sun brought with it the creation of life and it was its continued sustenance that preserved that life.

It was Amenhotep IV (1353-1336 BC) who introduced the worship of Aten at the expense of all other Gods even changing his name to Akhenaten in its honour. His attempt to introduce monotheism into Egypt much resisted at the time was to be short-lived however and ended with his death.

The most famous myth however is that of Osiris and Isis.

According to legend Osiris was murdered by his brother Set, who was jealous of his brother’s marriage to their beautiful sister Isis. Upon learning of the murder of her beloved husband and brother, Isis, the Queen of the Dead, searched high and low for the body. She found it in the land of the Phoenicians (modern day Libya) and brought it back to Egypt. Set was furious and ordered that the body be dismembered, and its parts be dispersed around the country.

Isis was not deterred, and she found all of her husband’s body parts except for his penis. Putting them all together she then performed the world’s first ever embalming and breathed life into the dead Osiris who resurrected went on to take revenge upon Set.

Despite the removal of his reproductive organ Isis gave birth to an heir by Osiris named Horus, from whom every following Pharaoh was said to descend. It was believed that the death and rebirth of Osiris was reflected every subsequent year in the agricultural cycle and Osiris was the guarantor of every harvest, and the Eye of Horus remains a symbol of protection and good fortune to this day.

The Egyptians believed the world to be flat, constant, and unchanging; the Earth God was Geb, the Sky Goddess Nut, and between the two was Air, governed by the God, Shu. Beneath the Earth lay the Underworld infinite in its expanse and eternal in its being. Here reigned the God Nu and he had done so since the dawn of Creation.

In the darkness of the Underworld lay chaos and so every day the Sun God Ra traversed the Earth and at night he passed through the Duat, the mysterious place of death and resurrection, to emerge the following morning reborn ensuring that life would continue.

This was always more than a myth it formed part of a belief system that determined how Egyptians saw themselves in the world, and nothing was more important in Egyptian life than death. They believed that all human beings possessed a life force known as Ka which leaves the body at the moment of death. This life force could be maintained even after death however by frequent offerings of food.

Every person also possessed a Ba, a spiritual essence unique to each individual that had to be released from the body after death so that it could rejoin the Ka and live on in eternity as the Akh. It was therefore important that the body be preserved so that the Ba could return to it at night to receive new life and be reborn each new day as the Akh.

The continued preservation of the body required constant maintenance particularly during the searing heat of the Egyptian summer and to do so was hard work and extremely expensive. As such, it was beyond the means of most commoners whose existence could be preserved but only in the bleak, unforgiving environs of the Underworld.

The literature of death was as ubiquitous in Ancient Egypt as its Gods, particularly the so-called Funerary, or Coffin Texts. These were written to provide details of the Underworld and were self-help manuals in how to avoid its hazards. Other such texts included the Book of the Caverns and the Book of the Gates. They all described the deceased person’s journey through the Afterlife.

The most famous of the Funerary Texts was the Book of the Dead, first developed in the Ancient Egyptian capital of Thebes around 1700 BC. It was a descendant of the Pyramid Texts that were for the exclusive use of the Pharaohs and by 1550 BC had become the standard text for prosperous Egyptians.

The Book of the Dead placed great emphasis upon spells, incantations, and imprecations that would be written on papyrus scrolls placed in the coffin, or on the shrouds that covered the body of the deceased. They would outline the dangers that were likely to be met and the best way of avoiding them and every aspect of the deceased’s journey through the Afterlife would be covered including the names of those they might encounter along the way. It was believed that to write down the name of someone you knew, especially an enemy, gave you power over them.

A Book of the Dead was produced by professional scribes often to order and many years in advance of the procurer’s demise. For those who could not a afford a personalised account of their lives as a guide to eternal salvation there were standard texts produced in Funerary Workshops where the name of the deceased could be added later. A typical inscription would read: “We now return our souls to the Creator, as we stand on the edge of eternal darkness.”

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: