Anne Boleyn: The Goggle-Eyed Whore

Posted on 27th August 2021

Anne Boleyn was born in Norfolk sometime in 1501, the second daughter of the diplomat Thomas Boleyn and his wife Anne Howard. As a result of her father’s profession, though born in England, she was raised mostly abroad.

She first came to the attention of Henry VIII at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, that lavish extravaganza of Kingly display and Royal authority that took place just outside Calais between 7th and 24th June 1520. At the time Anne was serving as Maid of Honour to Queen Claude of France.

Indeed, she was to spend seven years at the French Court which with its music, dancing, poetry, provocative fashions and emphasis upon flirtation made for a sexually charged environment that simply wasn’t to be found at its more formal and deferential English counterpart.

It comes as little surprise then to find that French etiquette and courtly manners were greatly admired - and the young Anne Boleyn had been well-schooled in both.

Having returned to England in 1522, Anne announced herself to the Royal Court when wearing a white satin dress embroidered with gold thread, she made a stunning appearance (alongside the King’s sister, Mary) as one of the dancers at the Green Castle Pageant held in honour of the Ambassador for the Holy Roman Empire – it did not go unnoticed.

But it was not merely her appearance that caught the eye and provoked the senses, her other attributes were no less evident; she was lively and playful, stayed up late into the night, played dice and cards; she was no less at home with the more masculine pursuits of archery, hunting and falconry. Clever, witty and fun to be around she was in other words good company and had no lack of suitors. Indeed, she enjoyed the chase playing the games of love with an expert hand.

In March 1526, Henry began to actively pursue Anne, though it is likely he had expressed an interest much earlier for in 1523 her engagement to Henry Percy, heir to the Duchy of Northumberland, had been broken off following the intervention of Cardinal Wolsey. It had been love and so when Percy married another soon after, Anne was left distraught. Her enmity towards the Cardinal dates from this moment and never relented – she was not one to forgive and forget.

Even so, she continued to have affairs one of which was with the poet Sir Thomas Wyatt who ended the relationship upon learning that the King shared his passion expressing his trepidation plaintively in the sonnet Who So Wish to Hunt: “Graven in diamonds with letters plain there is written her fair neck roundabout. Noli me bangure (do not touch me) for Caesar’s I am.”

A King was expected to have mistresses and in this regard Henry did not disappoint but it was assumed that sharing the King’s bed was not the same as sharing his throne; and this was not his first pursuit of a Boleyn either for he had been in a relationship with Anne’s sister Mary whom he had made his official mistress and the family had prospered as a result even if it meant Mary being referred to as the ‘King’s Whore.’ But she had since been rejected and their star had waned as a result. The lesson had been learned however, Mary had given herself too freely and now he had resumed his interest in the other Boleyn girl Anne, she would not make the same mistake - the King would have to earn her affection: when he offered to make her his official mistress she refused outright, his letters went unanswered, his gifts were returned unopened and when his presence became overbearing she dismissed herself from the Royal Court and returned home to Hever Castle in Kent. Her refusal to be seduced drove Henry to distraction but he had to learn – if he wanted her for his bed, he would have to marry her. She would never be his mistress she would only ever be his Queen.

Henry’s determination to win the hand of Anne Boleyn might surprise us now for she was far from conventionally beautiful but then similar to a previous femme fatale, the Egyptian Queen Cleopatra, her powers of seduction lay mostly elsewhere. The Venetian diarist Marino Sanuto who encountered Anne on a royal visit to France in October 1532, described her as: “Not one of the handsomest women in the world being of middling stature with a swarthy complexion, long neck, wide mouth, with a bosom not much raised but with eyes that are black and beautiful.”

Nicholas Sanders, a Catholic propagandist who had little reason to admire Anne Boleyn and every reason not to was even less flattering: “Anne Boleyn was rather tall of stature with black hair and an oval face of a sallow complexion as if troubled by jaundice.”

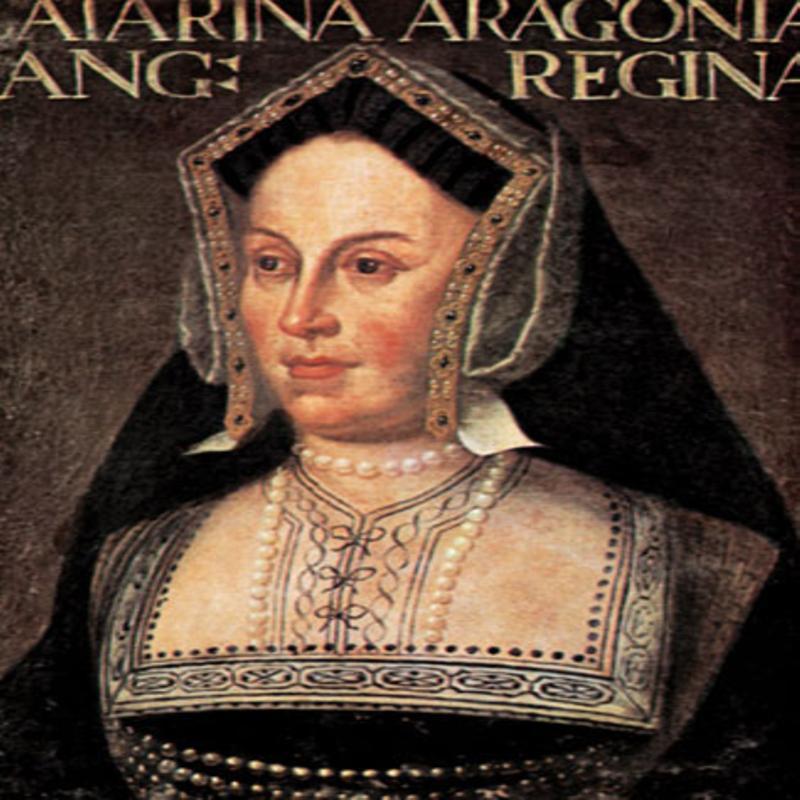

She was perhaps wisely referred to as beautiful in most contemporary accounts, but descriptions drawn from the secrecy of the diplomatic bag declare her attractive at best and rarely strikingly so. It was in Anne’s skilful use of her feminine wiles that her charm lay and never more so than when contrasted to Henry’s pious, dignified, courtly and deferential Queen Catherine of Aragon, a goodly wife but a dull mistress.

Atypically Spanish in appearance with her red hair, pale skin, and blue eyes Catherine had once been described as the ‘most beautiful creature in the world’ but she had few of Anne Boleyn’s charms and despite such a fervent admirer as Thomas More declaring there to be ‘few women in the world comparable to our Queen’ in middle age she had become plump and increasingly dowdy in appearance.

Despite his later behaviour suggesting otherwise Henry VIII was a devout Catholic and a regular Bible reader who not only wanted a divorce from his wife but also sought God’s sanction for doing so.

Catherine had not borne him a surviving son and heir and Henry now doubted she ever would for he believed he had been cursed with childlessness for marrying the widow of his deceased older brother, Arthur. Catherine was barren because they had sinned (the birth of a daughter Mary, the death of an infant son and the many still born counted for nothing) and he found evidence for his belief in a passage from Leviticus: “If a man shall take his brother’s wife, it is an unclean thing, he hath uncovered his brother’s nakedness and they shall remain childless.”

But Catherine had sworn under oath and before God that her marriage to Arthur had never been consummated and that she remained virgo intacta and a Papal Dispensation had been received for her to marry Henry on these grounds. Should she now retract, or at least cast doubt upon the accuracy of her previous statement, then her marriage to the King could be dissolved as illegitimate and he would be free to wed Anne Boleyn.

But when it was suggested to Catherine that she do as His Majesty wished and simply retire from public life, perhaps to a nunnery, she remained steadfastly defiant replying: “God never called me to a nunnery I am instead the King’s true and legitimate wife.”

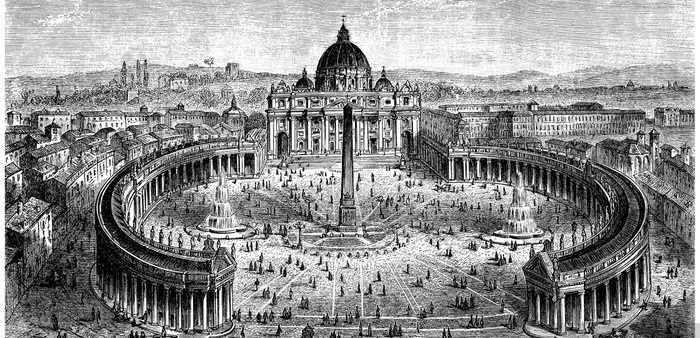

Henry appealed to the Vatican to grant an annulment of his marriage regardless of the Queen’s wishes and placed the affair of the’ King’s Great Matter’ in the safe hands of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey confident that his ever-reliable Lord Chancellor would secure the divorce. Even so, he also made a secret approach to Pope Clement VII requesting he simply waive the divorce through as the Dispensing Bull of his predecessor but one, Julius II, had been procured under false pretences; but events in Rome took a turn for the worse when on 6 May 1527, the city was sacked by the forces of Charles V who was not only the King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor but the nephew and therefore protector of Catherine of Aragon. Now a virtual prisoner within the confines of the Vatican it would not be possible for Pope Clement to grant Henry his divorce even if he had chosen to do so.

In the meantime, Wolsey presented the King’s case to Pope Clement, it rested upon three key points; firstly, that the original Dispensation was illegal as it contravened Biblical teaching as clearly laid out in the Book of Leviticus; secondly, that the original document had been incorrectly worded thereby making it void; thirdly, that the divorce of an English King should be tried in an English Court over which he as Papal Legate should preside.

The second claim was withdrawn when a correctly worded copy of the Dispensation was discovered in Spain but then it little mattered for everyone knew that the validity of the marriage rested upon whether Catherine’s earlier marriage to Prince Arthur had been consummated, and its outcome upon whether or not Cardinal Wolsey could control proceedings.

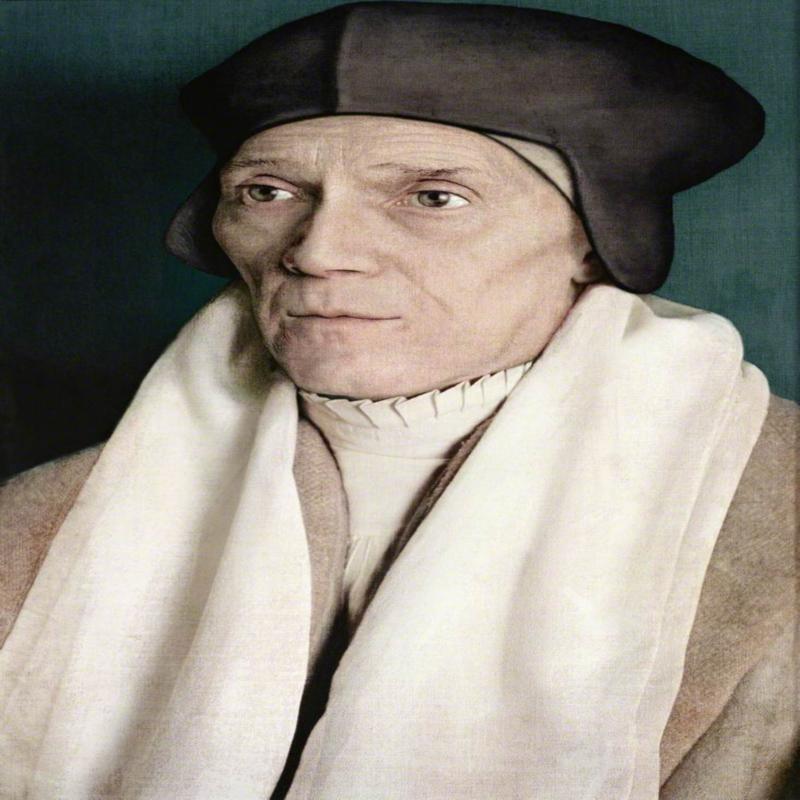

Thomas Wolsey had been King Henry’s Lord Chancellor and a Prince of the Church for more than a decade, he was a politician without peer, a statesman of renown and in religious affairs a virtual law unto himself. Henry VIII may have been the final arbiter on all affairs domestic and foreign, but Wolsey was their architect. There was no scheme adopted, no document signed, no legislation passed that did not have his fingerprints on them.

More than anyone else he had been responsible for legitimising the Tudor regime and establishing England as a major player on the European scene. He was confident of concluding the issue of the divorce to the King’s satisfaction, he told him so, and there were few who would argue with him. But this was an issue that went beyond the mere governance of the realm, it was personal to the King, and there were powerful forces at play.

Pope Clement acceded to Wolsey’s demand that the trial be held in England far away it was assumed from interference by Charles V but with caveats - the Court would be presided over by his trusted factotum Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio, and the final decision was to be made in Rome based upon his recommendations.

Unsure of his own position since the sack of Rome the Pope did not want a decision made however, rather he wanted a decision delayed and Campeggio was to fulfil this remit to the letter – he would arrive late for meetings, feign illness at every opportunity and hold proceedings up while he awaited instructions from the Vatican.

In October 1528, Wolsey established his Ecclesiastical Court to rule upon the validity of the King’s marriage to Queen Catherine at Blackfriars in London. Campeggio, who was already in England, delayed travelling to Blackfriars for almost two months not arriving until 3rd December. He then engaged in a series of meetings with Wolsey, often in the presence of the King, where he outlined the position of the Vatican while taking testimony from leading theologians and evidence gathered by legal scholars.

Well-schooled in the art of diplomacy the silver-tongued cleric was able to convince both Wolsey and the King of the sincerity of his endeavours and those of the Pope but frustration soon began to set in as one difficulty after another delayed the process.

After months of hearing evidence and taking legal advice on 21 July, King Henry VIII appeared before the Court to argue in person his case for a divorce. Also, due to testify was Queen Catherine while watching from the wings but hidden from view was Anne Boleyn.

The King spoke first, he remarked upon his love for the Queen, of his devotion to her person, and that he was seeking an annulment of his marriage not for reasons of lust or because he desired a younger woman but rather that the consummation of her previous marriage to his older brother Arthur had rendered their union unclean, a sin before God and therefore unlawful.

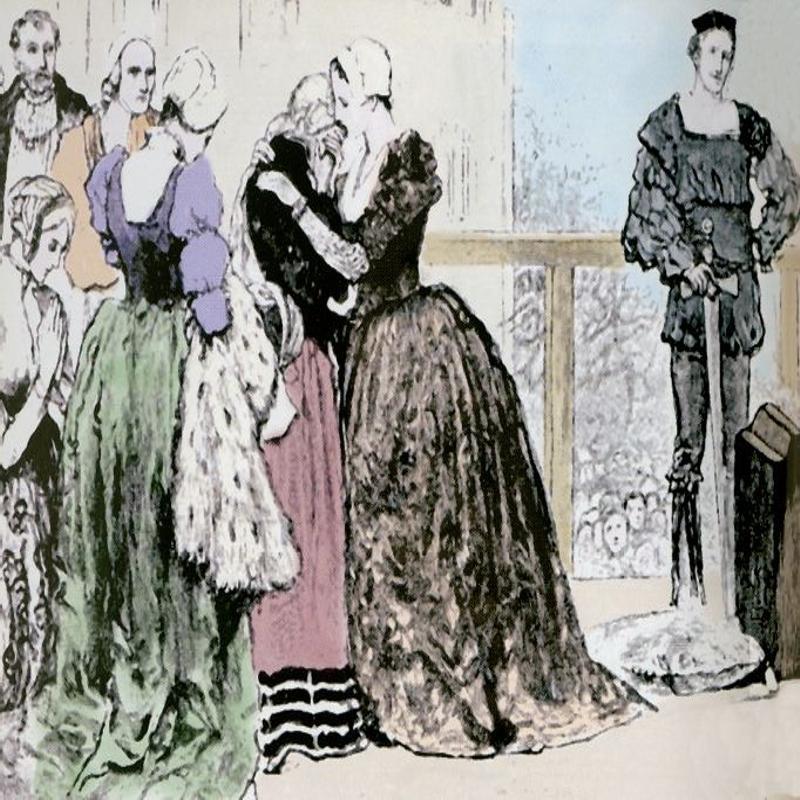

There had been murmurings of discontent throughout the King’s address from the many clerics present, sotto voce perhaps, but evident nonetheless. As he returned to his seat so Catherine was called to speak and a deathly hush descended upon the Court as she threaded her way past the many ushers and guards present towards where the King was sitting. Then in a moment of high drama she threw herself down in supplication before him. Henry was so taken aback he tried to raise her up only for Catherine to throw herself down once more this time even more emphatically. Then with tears in her eyes she spoke clearly and plainly, her voice strong and only occasionally faltering:

“Sir, I beseech you for all the love that hath been between us, and for the love of God, let me have justice. Take of me some pity and compassion, for I am a poor woman, and a stranger born out of your dominion. I have no assured friends, and much less impartial counsel. Alas! Sir, wherein I have offended you, or what occasion of displeasure have I deserved! I have been to you a true, humble and obedient wife, ever comfortable to your will and pleasure, that never said or did anything to the contrary thereof, being always well pleased and contented with all things wherein you had any delight or dalliance, whether it were in little or much. I never grudged a word or countenance, or showed a visage or spark of discontent. I loved all those who ye loved, only for your sake, whether I had cause or no, and whether they were my friends or enemies. This twenty years or more I have been your true wife and by me you had divers children, although it hath pleased God to call them out of this world, which hath been no default in me.

When ye had me at first, and I take God to be my judge, I was a true maid without touch of man. And whether it, be true or not, I put it to your conscience. If there be any just cause by the law that ye can allege against me either of dishonesty or any other impediment to banish and put me from you, I am well content to depart to my great shame and dishonour. And if there be none, then here, I most lowly beseech you let me remain in my former estate. Therefore, I most humbly require you, in the way of charity and for the love of God – who is the just judge – to spare me the extremity of this new court, until I may be advised what way and order my friends in Spain will advise me to take. And if ye will not extend to me such impartial favour, your pleasure then be fulfilled, and to God I commit my cause!”

With that she rose to her feet and briefly curtsied before turning on her heels and walking out. Three times she was ordered to return but staring straight ahead refused to do so. When one of her attendants breathlessly informed her, “Madam, they wish you to return” she replied, “It matters not, this is no indifferent Court for me. I will not tarry.” As she emerged from the building it was to the cheers of the people gathered outside particularly the many women in the crowd.

Catherine had earlier denied the right of the Court to rule on the validity of her marriage to the King and as such had appealed directly to the Pope for a decision. In light of this and the unsatisfactory conclusion to the day’s events Cardinal Campeggio suspended further proceedings until October when Pope Clement could be expected to declare his verdict – the Court would never meet again.

The events at Blackfriars had not only seen the King humbled in the sight of his subjects but had ended in farce with Queen Catherine more popular than ever and her intended replacement Anne Boleyn demonised far and wide as that Goggle-Eyed Whore. Indeed, the prevailing mood was that with the Court suspended, the Papal Legate returning to Rome, and the case no nearer a resolution the King of England had been led up the garden path and down a blind alley.

Henry VIII was not a man, and even less so a King, who looked kindly upon failure and his Lord Chancellor had failed him. That Wolsey had never done so before was his defence but with few friends willing to speak on his behalf and a great many enemies wanting to see the ‘Butcher’s Son’ brought to heel, once would prove enough. Henry would never forgive him for betraying his trust and making promises he could not keep but mindful of his past service there would be no further punishment for now. Yet in truth, the anger he felt towards his confidante, sometime friend, and devoted servant could only ever be transient. It would take others to make it permanent.

Anne Boleyn had hated Wolsey ever since he had forced her to break her the engagement to Sir Thomas Percy. She was also aware that he would often refer to her as that ‘foolish little girl’, now she believed that he had conspired with Cardinal Campeggio to delay the proceedings of the Ecclesiastical Court long enough for the King to fall out of love with her.

Not long after the case for the annulment had been referred back to Rome, she witnessed Henry and Wolsey sharing a convivial moment together. That night at dinner with the King she made reference to it: “What things hath he wrought to your great slander and dishonour, there is never a nobleman within this realm that had he done but half what he hath done, he were well worthy to lose his head.”

Henry appeared dismissive at first, “Why then I perceive you are not the Cardinal’s friend.”

But he would act on her words.

Not long after this exchange between the King and his mistress Wolsey was removed from office, stripped of his wealth and property, banished from Court and exiled to the provinces but he remained a Cardinal, Papal Legate and Archbishop of York so could not yet be considered a broken man. He remained determined to resurrect his career but his enemies, prominent among them the Boleyn family, were no less determined to prevent him from doing so.

The rumour soon began to circulate that he was involved in a plot to kidnap Anne Boleyn and have her smuggled abroad. Ordered to return to London to explain himself on 29 November 1530 while resting in Leicester he died. Although he had been ill for some time his death was still unexpected but it had perhaps been timely for it almost certainly saved him from a charge of treason and a less dignified and peaceful end.

As he lay upon his sick bed the once most powerful man in England aside from the King himself who had been brought low by that ‘foolish little girl’ remarked somewhat despairingly: “If only I had served God as diligently as I served the King, he would never have brought me to this.”

Any jubilation felt on Anne’s part at Wolsey’s downfall was tempered somewhat by Henry’s choice of Sir Thomas More as his successor.

A lawyer by profession Sir Thomas More was a renaissance man, a humanist, a theologian of international renown and one of the leading intellectuals of his day but he was also religiously orthodox, a believer in the primacy of the Church and a firm if not always explicit or vocal, opponent of the divorce. He had been both a friend and mentor to Henry since he was a young man and they spent many an hour together staring at the heavens and discussing God, astronomy and philosophy. Indeed, he had tutored the young King on governance and helped him write the book that would earn him the title Fedei Defensor or Defender of the Faith from a grateful Pope.

They had a special bond but if Henry thought that their relationship would see Sir Thomas lend him his support regarding the divorce then he was to be sorely mistaken. It was however agreed between them that if Sir Thomas would remain silent on the issue of the divorce then Henry would not involve him. His silence however, would prove deafening.

While Lord Chancellor More turned a blind eye to the divorce in favour of eradicating the Lutheran heresy from England the King’s secretary, Thomas Cromwell was busying himself unpicking the very fabric of Papal authority in the country.

The ambitious Cromwell who had learned the dark arts of good governance as secretary to the master himself Cardinal Wolsey, was in fact one of those very heretics whom Sir Thomas More was burning at the stake. He was a Protestant and denied the authority of the Pope but he was cynical and pragmatic enough to remain circumspect about such things, for now.

Even so, it was he who put it to Henry that as the divinely appointed King of England he need not seek permission of the Vatican to annul his marriage – he could award himself the divorce. Henry, nervous of excommunication and of imperilling his soul had yet to be convinced but he did little to impede Cromwell in his endeavours.

Working closely with the Boleyn family chaplain Thomas Cranmer and with the support of Anne herself, who had earlier presented Henry with a copy of the Protestant reformer William Tyndale’s ‘Obedience of a Christian Man’ which advocated for the Divine Right of King’s over and above the authority of the Pope, Cromwell was bit by bit legitimising the future break with Rome.

Anne, who kept a copy of a Tyndale Bible on a lectern in her Bedchamber and insisted her ladies-in- waiting read aloud a passage from it every day, formed, along with both Cromwell and Cranmer, an influential triumvirate of Protestant reformers at the heart of English governance – just how influential was yet to be seen.

In the meantime, Henry’s attitude towards Catherine hardened no doubt encouraged by Anne who didn’t merely consider the Queen an impediment to her own ambitions but had learned to dislike her intensely while serving as her Maid of Honour. She considered her proud, obstinate, dull and resented her piety. She wanted her out of the way and cajoled Henry night and day into breaking completely with his Queen forcing him to deprive Catherine of her rooms at Greenwich Palace before in the winter of 1531 notifying her that she was no longer to attend Court. Instead, she was to remain at More Manor House in Rickmansworth some twenty miles from London. Catherine wrote of her despair to Charles V in Vienna: “My tribulations are so great, my life so disturbed by the plans daily invented to further the King’s wicked intention, the surprises which the King gives me, with certain persons of his council, are so mortal, and my treatment is what God knows, that it is enough to shorten ten lives, much more mine.”

With Catherine removed from his presence Henry declared himself separated from his Queen and began to live openly with Anne.

On 1 September 1532, Henry made Anne Marquess of Pembroke, her father the Earl of Wiltshire and her brother George, Viscount Rochford while her sister Mary was provided with a pension. Other members of the Boleyn family were similarly rewarded.

That autumn, in what could be considered her first official engagement alongside the King she accompanied Henry to Calais for a meeting with the French King Francis I. She performed her role impeccably, she was elegant, gracious, conversed with nobles, debated with clerics, met with ambassadors and King Francis was happy to call her Majesty.

She was every inch the Queen, except she wasn’t Queen – but that would soon change.

Soon after their return to England, Henry and Anne were married in secret. Upon discovering she was pregnant Anne insisted that the marriage service be repeated and so on 23 January 1533, a second wedding ceremony took place in London as revealed by Thomas Cranmer in a letter to his friend Archdeacon William Hawkins just prior to the coronation: “But now, Sir, you may not imagine that this coronation was before her marriage; for she was married much around St Paul’s Day last, as the condition thereof doth well appear, by reason she is now somewhat big with child.”

On 23 May 1533, a special Court was convened at Dunstable Priory under the auspices of the recently appointed Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer to pronounce upon the validity of the King’s marriage to Queen Catherine. Henry would not on this occasion make the case for the divorce himself, although Catherine was summoned to attend as the old arguments were trundled out once again even if this time the testimony taken wasn’t intended to lay bare the facts but merely to prove that due process had been undertaken.

Little time was required to pass a verdict that had long been pre-determined - the King’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon was annulled on the grounds that it was contrary to the law of God and the law of the land. Three days later Cranmer made public the King’s marriage to Anne Boleyn and declared it legal.

After seven long years of fraught courtship and interminable legal wrangling Henry had at last triumphed and Anne Boleyn was his Queen, but what had taken so long to put together would prove much easier to tear asunder.

The Fallen Idol

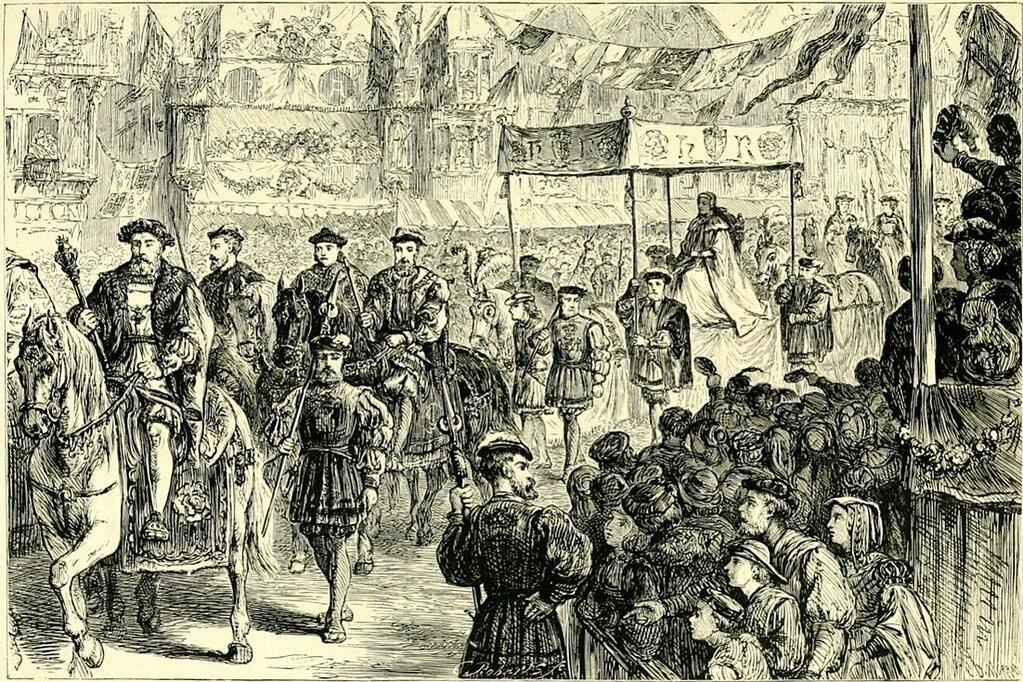

Late in the afternoon of 31 May 1533, in what would be a great procession through the streets of the city, England’s new Queen, Anne Boleyn, left her temporary residence in the Tower of London for the place of her coronation at the Palace of Westminster.

Only two of Henry VIII’s six wives would be afforded the honour of a formal coronation, the other was Catherine of Aragon, but that had not been his doing. With Anne already heavily pregnant, a fact artfully disguised where possible, the event could have been seen as an occasion for much mirth and mockery even if the Queen’s condition did lend proof of the King’s virility, he had earlier been stung by the Spanish Ambassador Eustace Chapuys casting doubt upon whether, at his age, the King could still sire a son, prompting him to respond angrily - Am I not a man like any other!

Given the mood of the country Henry had, perhaps wisely, chosen to stay away though he would be present for the celebrations. Even so, determined to make a statement no expense had been spared on the spectacle.

The Tudor chronicler Edward Hall, who was present, provides us with an account of the scene as he would also of Anne’s coronation the following day:

“And on Saturday, the last day of May, she rode from the Tower of London through the city with a goodly company of lords, knights, and gentlemen, richly apparelled. She herself rode in a rich chariot covered with cloth of silver, and a rich canopy of cloth of silver borne over her head by the four Lords of the Ports, in gowns of scarlet, followed by four richly hung chariots of ladies, and also several other ladies and gentlewomen riding on horseback, all in gowns made of crimson velvet. And there were various pageant made on scaffolds in the city; and all the guilds were standing in their liveries, every- one in order, the mayor and aldermen standing in Cheapside. And when she came before them the Recorder of London made a goodly presentation to her, and then the mayor gave her a purse of cloth of gold with a thousand marks of angel nobles in it, as a present from the city; and so the lords brought her to the Palace of Westminster and left her there that night.”

The thousands of people who lined the route patiently waiting for the procession to pass and eager to catch a glimpse of their new Queen were entertained by the many jugglers, acrobats, fire eaters and musicians present while young children, many in fancy dress, danced and made merry.

The procession paused briefly at St Martin’s Church on Ludgate Hill where prayers were said, recitations made, and a choir sang in the Queen’s honour but the carnival atmosphere, tempered by such moments of reverence and solemnity, was not all it seemed. The Queen’s reception was mixed at best, the crowds were enjoying the festivities no doubt, but the cheers rang hollow and were often drowned out by reciprocal jeers and catcalls despite the many there who had been amply rewarded for their presence.

But the moments of discord did little to diminish the occasion and Anne took it all in good heart her countenance remaining pleasant to gaze upon throughout- she knew the people would love her well enough when she provided the King with a son and heir.

The following day Anne “was brought to St Peter’s Church at Westminster, and there sat in her high royal seat which was on a raised platform before the altar. And there she was anointed and crowned Queen of England by the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Archbishop of York.”

Upon being crowned Queen, Anne was immediately taken to nearby Westminster Hall where the great and good of the land, with the notable exception of Sir Thomas More, had gathered for the lavish celebratory banquet in her honour. Sitting at high table accompanied only by the Archbishop of Canterbury while the King looked on, the clearly exhausted and heavily pregnant Anne did not wilt outperforming all present with her ease of presence, pleasant demeanour, eating heartily and dancing late into the night with her new husband Henry, King of England.

The festivities continued for another two days with tournaments, further banquets and other sundry entertainments. It was a triumph for both Henry and Anne, the cup of goodwill runneth over and was imbibed with great relish, but the sound of dissenting voices were never far away and as long as Catherine of Aragon’s shadow loomed large over events and the King remained without a male heir an atmosphere of uncertainty would prevail.

By now exiled to Kimbolton Castle in remote Huntingdonshire far removed from the Royal Court in London and the centre of power, Catherine refused to be cowed by the King’s bullying and not very subtle acts of intimidation insisting that she was still the “King’s only lawful wedded wife and England’s rightful Queen.” Moreover, and much to Henry’s chagrin, she demanded her servants refer to her as such and she could still count among her friends many influential people none more so than the Lord Chancellor Sir Thomas More and John Fisher, the Bishop of Rochester.

Since the annulment of the marriage Catherine had been relegated in status to Dowager, Princess of Wales, starved of funds and had seen her household reduced to the bare minimum required as Henry maintained the pressure on her to accept the divorce and his marriage to Anne Boleyn as the fait accompli it clearly was but despite the promise of improved relations and conditions should she relent Catherine stubbornly refused to do so. As a result, she was denied permission to meet or even communicate with their daughter Mary – they were in fact never to see one another other again.

On 7 September 1533, Anne Boleyn gave birth to a healthy baby girl she named Elizabeth. Henry went through the formalities of recognising her as his daughter, but he could barely disguise his disappointment. He had married Anne in the belief she would provide him with the son and heir he so craved now she had failed to deliver. She would soon be pregnant again Anne reassured him, but he had divorced Catherine believing he had sinned in marrying his brother’s widow and so had been cursed to remain without male offspring. He was still without male offspring - had she deceived him? All celebrations were quietly put aside, the great joust that had been arranged in the baby prince’s honour was cancelled, and Henry did not call upon Anne again for some time.

Henry’s determination to divorce Catherine and marry Anne had also set in motion a series of events unforeseen and unimaginable just a few years before.

In order to secure the divorce denied him by the Vatican Henry had first to break with Rome, an issue that had acquired greater urgency since Pope Clement VII had declared his marriage to Catherine legal.

In May 1532, at the Convocation of Canterbury the clergy yielded to the King’s demand that it abandon its right to formulate Canon Law without his consent or in future seek instruction from or implement any policy emanating from Rome – the Pope’s jurisdiction would no longer run in England.

The Submission of the Clergy, as it became known, was not passed without opposition. John Fisher, the Bishop of Rochester, was particularly hostile urging fierce resistance but the Archbishop of Canterbury William Warham, who despite seeming lukewarm at times had been a long-time supporter of Catherine of Aragon was now old, ailing and his resolve weak - he would carp and complain but not resist the King who had made it clear in a speech before parliament how any such opposition would be regarded: “Well beloved subjects, we thought that the clergy of the realm had been our subjects wholly, but now we have well perceived that they be but half our subjects, yea, and scarce our subjects.”

This was soon followed by the Act of Supremacy which recognised King Henry VIII and his subsequent successors as Head of the Church in England. The Pope would in future be referred to as the Bishop of Rome.

Upon learning that the clergy had submitted to the will of the King and signed the Oath of Supremacy, Sir Thomas More resigned as Lord Chancellor. He would not take the Oath, but neither would he speak against it, and Henry, though disappointed appeared at first willing to let his old friend and mentor be. Thomas Cromwell, in effect the King’s Chief Minister and master manipulator in a variety of roles was not, he would not let sleeping dogs lie. As long as Sir Thomas refused to publicly submit as others had he remained a threat to the religious reforms he was so assiduously working to impose; time and again Sir Thomas was interrogated whether it be over accusations of bribery while in office or over his association with Elizabeth Barton, the Holy Maid of Kent, who had prophesied against the King’s relationship with Anne Boleyn.

There was little evidence of wrongdoing against the former Lord Chancellor as Cromwell knew full well but then it was about bringing pressure to bear, pressure to take the oath. If he did so then the King’s generosity would know no bounds, if he did not then intimidation would suffice – and so it would prove.

In March 1534, the Act of Succession declared the King’s daughter by Catherine of Aragon, the Princess Mary, a bastard and removed her from the line of succession. At the same time Anne Boleyn’s daughter, the Princess Elizabeth was elevated to be next in line to the throne. Those required to take the Oath would in effect be recognising Anne Boleyn as the legitimate Queen while the Treason Act passed around the same time made not taking the Oath a crime punishable by death.

Despite the severity of the penalty imposed for not doing so Sir Thomas More could no more swear this Oath than he could the previous one. If there had been an opportunity for him to do so, if the wording of the text had been different, if a loophole had existed, he would have taken it for he had no desire to lose his life as he made plain many times, but he could not act in defiance of his conscience and perjure himself before God.

On 17 April 1534, Sir Thomas More was arrested on a charge of high treason and taken to the Tower of London where he would remain for over a year in the hope the reality of imprisonment and the prolonged separation from his family would in the eyes of most at least, bring him to his senses.

Soon after Sir Thomas’s incarceration his friend and fellow Oath resister Bishop John Fisher was likewise arrested and taken to the Tower. Both men had taken shelter behind the legal precedent that silence implies consent, if so, their silence must have been the loudest in recorded history for it resounded throughout the Royal Courts of Europe. But whether spoken or otherwise, the wily Thomas Cromwell, acting on behalf of his master the King of England had long ago decided that such dissent could not be tolerated.

In May 1535, the recently installed Pope Paul III made Bishop Fisher a Cardinal in the hope that his elevation to a Prince of the Church would, if not secure his freedom, then at least save his life. Learning of this King Henry declared scornfully that should he receive his Cardinal’s hat in time he would gladly return it to Rome with the Primate’s head in it.

John Fisher was executed on 22 June 1535, not as a Cardinal or a Bishop but as a commoner and as a frightened, physically broken but stubborn old man.

Sir Thomas More could now be in no doubt as to his own fate and on 1 July was found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death on the perjured evidence of a former acolyte, Richard Rich.

Returned to the Tower to await his execution it was even now hoped that there may be a last minute recantation and swearing of the Oath, anything that might allow the King to commute his sentence to something other than death; but he had already publicly condemned the King’s marriage to Anne Boleyn and his usurpation of power in matters spiritual at his trial and so there was no acceptance now which might ever be thought true and sincere.

A final visit from his family who he had earlier ordered to swear the Oath for their own safety and during which emotions ran high could not sway him from his conviction. Not even the succinct and passionately argued reasonableness of his daughter Margaret to whom he was particularly close could change his mind.

Sir Thomas More met his fate that warm 6 July morning with all the calm resolution people had come to expect from one of the leading humanist thinkers of his day, though perhaps his spirit surpassed his body as ascending the steps to the scaffold he asked: “I pray you, Mr Lieutenant, see me safe up and for my coming down, I can shift for myself.” Before recompensing his executioner in assurance of a swift death, Sir Thomas addressed briefly those in attendance: “I die the King’s faithful servant, but God’s first.”

Perhaps the man in greatest pain that fine July morning was the one responsible for the death of his former Lord Chancellor. Perhaps the person who should have been most nervous was the woman who had sealed his fate.

Henry, who cared little for Bishop Fisher was deeply conflicted over the execution of Sir Thomas More. He had been his guide and mentor, his close friend and confidante since boyhood, now he was dead, and he was dead as a result of Anne Boleyn. He expressed his regret in private often in tones of bitterness and recrimination - but at least Anne would soon be pregnant once more and he would be vindicated in the eyes of God.

On 8 January 1536, news reached the Royal Court at Greenwich that Catherine of Aragon had died, and an overwhelming sense of relief swept through its environs as if caught in lightening and its dark corridors had been bathed in shafts of light. Both Henry and Anne were reportedly delighted though the proprieties of grief were respected and maintained even if some thought otherwise when the colour yellow (supposedly the colour of mourning in the late Queen’s native land) was ordered to be worn lending proceedings a more celebratory feel.

Aware that she was not long for this world Catherine had penned one final letter to her erstwhile husband:

My most dear lord, king, and husband

The hour of my death now drawing on, the tender love I owe you forceth me, my case being such, to commend myself to you, and to put you in remembrance with a few words of the health and safeguard of your soul which you ought to prefer to all worldly matters, and before the care and pampering of your body, for the which you cast me into many calamities and yourself into many troubles. For my part, I pardon you everything, and I wish to devoutly pray God that he will pardon you also. For the rest, I commend unto you our daughter Mary, beseeching you to be a good father unto her, as I have heretofore desired. I entreat you also, on behalf of my maids, to give them marriage portions, which is not much, they being but three. For all my other servants i solicit the wages due them, and a year more, lest they be unprovided for. Lastly, I make this vow, that mine eyes desire you above all things.

Katherine the Queen

Now Anne had all that she had ever wanted – she was married to the King, she was Queen, her daughter Elizabeth was in the line of succession, her opponents at Court and in the Church had been disposed of and her great rival Catherine of Aragon was dead. All she had to do in return was provide her husband with a son and heir.

On the day of the former Queen’s funeral Anne’s pregnancy bore fruit in the form of a stillbirth – the child would have been a boy. The King’s ill-temper was evident, if his Queen expected sympathy, she would get none from him. He now began to speak openly of being deceived and beguiled, bewitched even.

Henry and Anne’s love affair had rarely been less than tempestuous with the former driven by lust the latter by ambition. Anne’s natural vivacity, sharp intellect, independence of thought and outspoken ways so admired in a mistress were less so in a Queen. The expected deference was not forthcoming, neither was the silence of a dutiful wife. Henry and Anne argued often and loudly.

SShe could never truly be Queen while Catherine had lived no matter how hard she tried, and she did try living ostentatiously and with no expense spared adopting the airs and graces of regality to the uttermost. Even so, she remained an interloper, the King’s prostitute - that goggle-eyed whore. It made her spiteful towards her household, her husband, even her own sister but the primary target of her vindictiveness would always be Catherine. She demanded that her retinue be reduced, that she not be allowed visitors, that she hand-over her jewels, and that the minimum only be spent on her maintenance. The Princess Mary she made work in her infant daughter Elizabeth’s household ordering that she be closely watched and if heard make mention of the succession be severely beaten.

Now Catherine of Aragon was dead she was losing the King’s affections.

The Spanish Ambassador Eustace Chapuys, who was no friend to Anne Boleyn referring to her in his correspondence as the King’s concubine remarked of the stillbirth – the Queen has miscarried of her saviour. He could say this with some confidence as it was increasingly apparent that she was no longer in the King’s favour. He had earlier written: “It is heard in France that Anne Boleyn has in some way or other incurred the Royal displeasure and that she is in disgrace with the King who is paying his court to another lady, and other people are uttering words of much indignation against her.”

Anne had begun to fear for her safety and that of her daughter, Elizabeth. Already embroiled in a power struggle with Thomas Cromwell for influence over the King especially in the area of foreign affairs where she favoured an alliance with France rather than the closer ties with the Protestant States of northern Europe sought by the Chief Minister. She was also aware that one of her ladies-in-waiting Jane Seymour had caught the King’s eye. Indeed, upon discovering that she was wearing a locket given her by Henry, she tore it from her neck with such force that the violence involved frightened others present. But such temper tantrums were becoming increasingly commonplace. She felt increasingly isolated with her only salvation being her ability to provide the King with a son, and this she had been unable to do.

Rumours had long been circulating regarding the Queen, that she remained no more than the ‘King’s Whore’ just as her sister had been, and as the saying went – once a whore always a whore. Whether the charges that would be brought against her were then, entirely the invention of Thomas Cromwell or that he was merely exploiting these rumours it is difficult to say, but that they were readily believed is not.

Henry had already decided he was a victim of her witchcraft, that he had been seduced with evil intent. He too had heard the rumours and he wanted Thomas Cromwell to investigate them.

In April 1536, a young musician in Anne’s service Mark Smeaton was arrested and charged with being the Queen’s lover. To commit adultery with the Queen carried a sentence of death and so he at first frantically denied the charges but put to the rack soon confessed and implicated others.

On 1 May, Henry Norris, an old friend and jousting partner of the King’s, was likewise arrested. He was said to have expressed an unhealthy interest in the Queen visiting her often in her chambers and other arrests soon followed, a courtier Sir Francis Weston, a groom William Brereton and the poet Sir Thomas Wyatt but most damaging and hurtful was the detention of her brother George, Viscount Rochford on charges of committing incest with his sister.

KKept unaware of the details Anne was not heedless to the gossip and in desperation tried one last time to reconcile with her husband carrying the infant Elizabeth in her arms she pleaded her innocence and begged him not to forsake their daughter but Henry remaining impassive, and unmoved dismissed her from his presence.

On 2 May, Anne Boleyn was arrested charged with adultery and high treason and taken by river to the Tower of London where she entered by the notorious Traitor’s Gate. She appeared frightened and a little disbelieving of the fate that had befallen her. She asked often for news and her mood it was said swung from a calm indifference to hysterical fits of tears.

On 6 May, she wrote what would prove a last letter to her husband, the King:

Sir,

Your Grace's displeasure, and my imprisonment are things so strange unto me, as what to write, or what to excuse, I am altogether ignorant. Whereas you send unto me (willing me to confess a truth, and so obtain your favour) by such an one, whom you know to be my ancient professed enemy. I no sooner received this message by him, than I rightly conceived your meaning; and if, as you say, confessing a truth indeed may procure my safety, I shall with all willingness and duty perform your demand.

But let not your Grace ever imagine, that your poor wife will ever be brought to acknowledge a fault, where not so much as a thought thereof preceded. And to speak a truth, never prince had wife more loyal in all duty, and in all true affection, than you have ever found in Anne Boleyn: with which name and place I could willingly have contented myself, if God and your Grace's pleasure had been so pleased. Neither did I at any time so far forget myself in my exaltation or received Queenship, but that I always looked for such an alteration as I now find; for the ground of my preferment being on no surer foundation than your Grace's fancy, the least alteration I knew was fit and sufficient to draw that fancy to some other object. You have chosen me, from a low estate, to be your Queen and companion, far beyond my desert or desire. If then you found me worthy of such honour, good your Grace let not any light fancy, or bad council of mine enemies, withdraw your princely favour from me; neither let that stain, that unworthy stain, of a disloyal heart toward your good grace, ever cast so foul a blot on your most dutiful wife, and the infant-princess your daughter. Try me, good king, but let me have a lawful trial, and let not my sworn enemies sit as my accusers and judges; yea let me receive an open trial, for my truth shall fear no open flame; then shall you see either my innocence cleared, your suspicion and conscience satisfied, the ignominy and slander of the world stopped, or my guilt openly declared. So that whatsoever God or you may determine of me, your grace may be freed of an open censure, and mine offense being so lawfully proved, your grace is at liberty, both before God and man, since have pointed unto, your Grace being not ignorant of my suspicion therein. But if you have already determined of me, and that not only my death, but an infamous slander must bring you the enjoying of your desired happiness; then I desire of God, that he will pardon your great sin therein, and likewise mine enemies, the instruments thereof, and that he will not call you to a strict account of your unprincely and cruel usage of me, at his general judgment-seat, where both you and myself must shortly appear, and in whose judgment I doubt not (whatsoever the world may think of me) mine innocence shall be openly known, and sufficiently cleared. My last and only request shall be, that myself may only bear the burden of your Grace's displeasure, and that it may not touch the innocent souls of those poor gentlemen, who (as I understand) are likewise in strait imprisonment for my sake. If ever I found favour in your sight, if ever the name of Anne Boleyn hath been pleasing in your ears, then let me obtain this request, and I will so leave to trouble your Grace any further, with mine earnest prayers to the Trinity to have your Grace in his good keeping, and to direct you in all your actions. From my doleful prison in the Tower, this sixth of May;

Your most loyal and ever faithful wife, Anne Boleyn"

Yet even now she could not bring herself to believe that the King would truly do her harm; surely he would pardon her or banish her from Court, perhaps exile her to another country. It wasn’t until her trial on 15 May before a tribunal of 27 of the most prominent peers of the realm one of whom was her old paramour Henry Percy now Duke of Northumberland and presided over her own uncle the Duke of Norfolk that the implications of what was happening became truly apparent.

Anne defended herself as best she could knowing that the charges against herself and the others were false but there was little sympathy to be had and minds were closed and hearts cowed to judge other than the verdict predetermined:

“I am entirely innocent of all these accusations that I cannot ask pardon of God for them. I have always been a loyal and faithful wife to the King. I’ve not perhaps always shown him that humility and reverence that his goodness to me, and the honour to which he raised me, did deserve.

I confess I have had fancies and suspicions of him which I had not the strength, nor discretion to resist, and God knows and as my witness I have never failed otherwise towards him, and shall never confess any otherwise.”

It was an admission of sorts but of an entirely different guilt, perhaps.

The verdict was against her was unanimous, it could be no other, and so found guilty of incest, adultery and treason she was sentenced to death. Finally, informed that Archbishop Cranmer had the previous day declared her marriage to Henry null and void she realised that death awaited her and that there would be no reprieve.

The final few days of Anne’s confinement in the Tower were a torment to her she was in deep mourning for the fate of her brother and feared for the safety of her remaining family in particular her daughter. She repented at length the behaviour that had lost her the affection of her husband the King, doomed the lives of others likewise accused with her on trumped up charges and had brought her to this.

On 17 May, she may have seen and would certainly have heard the execution of her brother George and the other accused. She was due to be executed herself the following day but now there was a delay.

Henry had relented a little, Anne would be spared the indignity of the axe and instead an expert swordsman had been brought from Calais to ensure that the decapitation would be as swift and painless as possible, but the journey to London had taken longer than anticipated.

Anne’s final hours were spent reading the Bible in quiet contemplation of her fate, though her eyes were reddened and her cheeks rarely dry of tears. The Constable of the Tower Sir William Kingston who had warmed to the condemned Queen during the period of her confinement wrote of her final hours: “This morning she sent for me, that I might be with her at such time as she received the good Lord, to intent I should hear her speak as touching her innocence always to be clear. And in the writing of this she sent for me, and in my coming she said: “Mr Kingston, I hear I shall not die afore noon and I am very sorry therefore, for I thought to be dead by this time and past my pain.” I told her it should be no pain, it was so little. She said, “I heard say the executioner is very good and I have a little neck,” and then she put her hands around it, laughing heartily. I have seen so many men and women executed, and that they have been in great sorrow, and to my knowledge this lady has much joy in death.”

Dressed in a dark grey fur trimmed gown and red petticoats and accompanied by two ladies-in-waiting it was said she went to the scaffold as a lady out for stroll, taking in the air and with a bounce in her step uncommon to those condemned to die. She then addressed those present in a clear and unhesitating voice:

“Good Christian people, I am come hither to die, for according to the law and by the law I am judged to die, and therefore I will speak nothing against it. I have come hither to accuse no man, nor to speak anything of that, whereof I am accused and condemned to die, but I pray God save the King and send him long to reign over you, for a gentler nor a more merciful prince was there never and to me he was ever a good, gentle, and sovereign lord. And if any person should meddle of my cause, I require them to judge the best. And thus I take my leave of the world, and of you all, and I heartily desire you all pray for me. O Lord have mercy on me, to God I commend my soul.”

Many of those in attendance were reduced to tears by her humble demeanour and generous words for a King who had in truth shown her no mercy and people knelt to pray and there were cries of God save the Queen as Anne, blindfolded and on her knees before her executioner, her head held high, mumbled the words over and over “O sweet Jesus receive my soul. O Lord God, have pity on my soul.”

Little could Anne have anticipated the fate that awaited her when she coaxed and teased her way into the royal marriage bed, Queens were not executed, they might be banished, exiled, sent to a nunnery even but they were not put to death; but then a royal marriage was a political event that lay within the purview of the diplomats and dynasts. Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon was one such arrangement; his relationship with Anne Boleyn however was not, she had little political cachet, rather it was driven by passion and desire and as is often the case when such affairs cool they lead to bitterness, resentment and suspicions of betrayal.

Anne Boleyn’s generous words upon the scaffold might suggest otherwise but maybe she understood her role in turning the romantic, lovelorn prince of those early years into the monstrous tyrant of a decade later. After all, he had divorced a devoted wife, executed his friends and imperilled his soul for her and she had not delivered on the promises she had made. Perhaps, she was merely seeking to protect her daughter Elizabeth from any further retribution and secure her place in the line of succession. Then again, she may have meant every word she said.

The day after Anne Boleyn’s execution Henry became betrothed to Jane Seymour (that empty headed harlot, according to Anne) and nine days later they married. On 12 October 1537, she gave birth to a healthy baby boy, the future Edward VI. On 27 October, Jane Seymour died from puerperal fever contracted during childbirth.

Henry was saddened by the loss, but it mattered little – a Queen had done her duty, at last.

Share this post: