Baader-Meinhof

Posted on 21st August 2021

Germany had ended the Second World War a broken country with millions of dead, its cities reduced to rubble, its economy in tatters and under foreign occupation. It was an industrial wasteland and there were those who wished to keep it so.

Henry Morgenthau, the United States Secretary of the Treasury had proposed that Germany having divested itself of the right to ever again be included in the family of civilised nations should be divided and denuded of all its remaining industrial plant and machine tool making capability so that it would never again be able to adopt a war-like posture or pose a threat to its neighbours.

The Soviet leader Josef Stalin was eager to see the Morgenthau Plan implemented demanding that Germany’s heavy industry be dismantled immediately and transported to Russia as recompense for its losses during the war. President Roosevelt agreed as did Winston Churchill if reluctantly, but a change of leadership in both the United States and Great Britain along with a cooling of relations between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union was to see a change in policy.

The idea of an agricultural and economic vacuum at the heart of Europe was simply untenable and so Morgenthau’s proposals were eventually rejected in favour of an economic recovery programme known as the Marshall Plan after the American Secretary of State General George C Marshall.

The United States would provide massive financial assistance to rebuild the economies of Europe and no country would benefit more from its largesse than Germany, or at least its Western half for it had been formally divided in October 1949 when the Soviet Union established the German Democratic Republic with its capital in East Berlin.

But the German people worked hard to rebuild their country its economy and its institutions and as divided as it was the western half had by the 1970’s once again become the powerhouse of Europe. Yet to some this rush to renewed prosperity appeared to turn a blind eye to the recent past. It seemed a grey, consumerist society intent only on making and spending money while denying evil.

Yet if anyone was aware of evil it was the Germans and there was little doubt that a sense of collective guilt pervaded almost every as aspect of German life. Even so, it remained a deeply conservative society with many of its major institutions still run by those with links to the old tyranny. Similarly, professions such as finance, law, medicine and academia were still heavily populated with ex-Nazi Party members or supporters.

Many had a past best kept hidden and children still dared not ask what their parents did during the war or delve too deeply into the past of their amiable, grey haired old grandfather.

It was a society yet to be purged of its misdeeds but then it never could be despite an intensive programme of de-Nazification and so the stench of hypocrisy blew on each gust of wind and the air hung putrid with malfeasance in every dusty corridor.

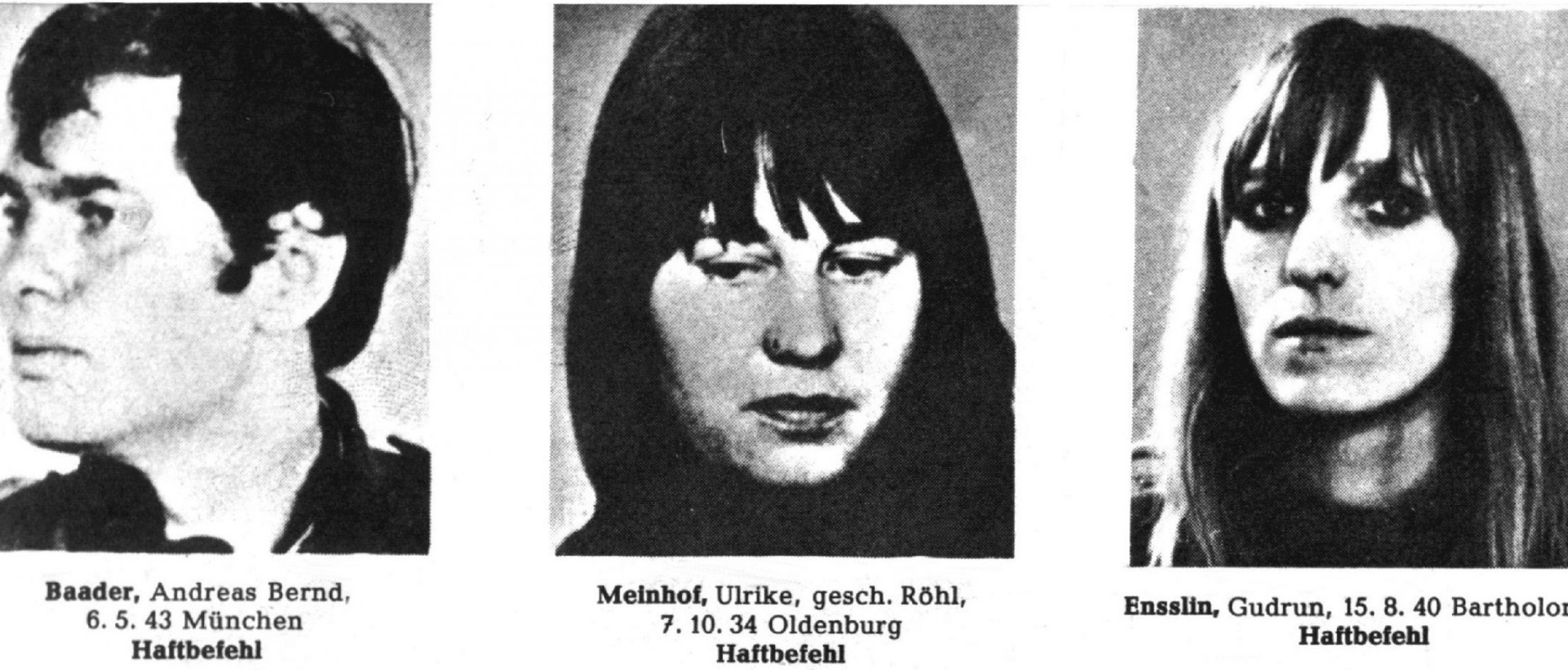

It remained what Gudrun Ensslin, a founding member of the Red Army Faction referred to as – the Auschwitz Generation.

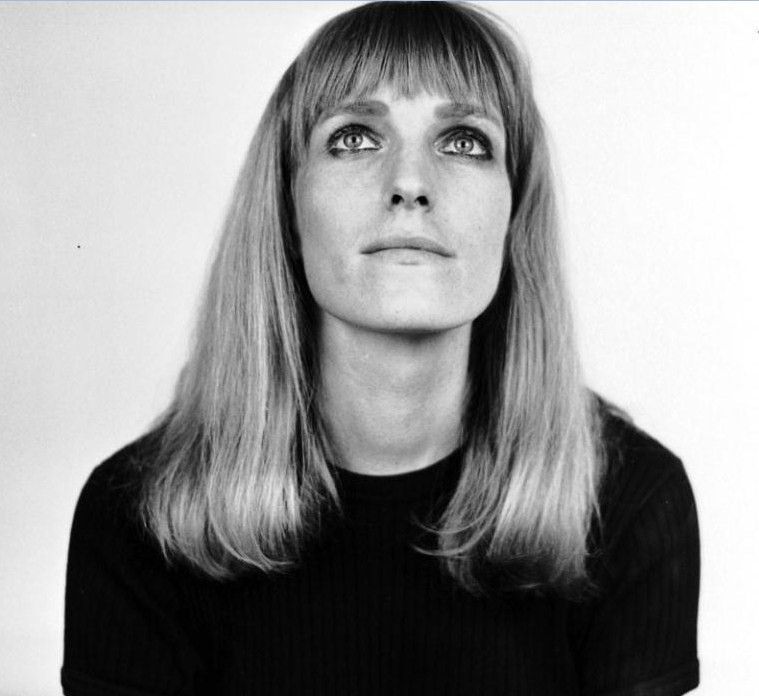

But this was not the world Ulrike Meinhof had been born into on 7 October 1934, in the Lower Saxony town of Oldenburg where her earliest memories would have been of the parades, banners and uniforms of a totalitarian society followed by the deprivation, destruction and fear of total war.

She was not herself the child of Nazis her parents being comfortably off academics with liberal views they wisely kept to themselves. Her father however died when she was aged just six and her mother eight years later and so, along with her sister, the remainder of her young life would be spent in the care of her mother’s lodger, Renate Riemeck, a remarkable woman who in a society where diversity was not tolerated and the reporting on a neighbours behaviour were commonplace she openly espoused left-wing views, often dressed as a man, and lived with her female lover all crimes for which she could have been sent to a Concentration Camp, or worse. She was to have a considerable influence on the young Ulrike’s life.

In 1957, Ulrike enrolled at the University of Munster to study philosophy and sociology quickly becoming involved in left-wing student politics protesting the rearming of the Bundeswehr (German Army) and the deployment of American nuclear weapons on German soil. In 1959, she joined the still proscribed Communist Party and after graduating from University found work on the staff of the left-wing journal Konkret becoming by 1962 its effective Editor. Putting aside any talent for journalism her meteoric rise may be in part down to her marriage in 1961 to the magazines founder and publisher Klaus Rainer Rohl by whom she had twin daughters.

As the 1960’s progressed Ulrike began to earn the reputation as a respected social commentator appearing regularly both on television and the radio. Indeed, she and her husband were something of a celebrity couple in left-wing circles. But merely commenting on the iniquities and injustices of life as she saw them was never enough, the world was changing, and she wanted to help change it.

Young people were no longer the mere ciphers of their parents – the feminist movement was becoming increasingly influential, homosexuals were out and proud, the anti-nuclear movement was growing hand protests were occurring in cities across the world against American military intervention in Vietnam.

Ulrike was uncomfortable in a profession she considered deceitful and was tired of being a desk bound philosopher, she was becoming increasingly radicalised and militant and it was at an anti-Vietnam War demonstration in the summer of 1968 that she first met Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin.

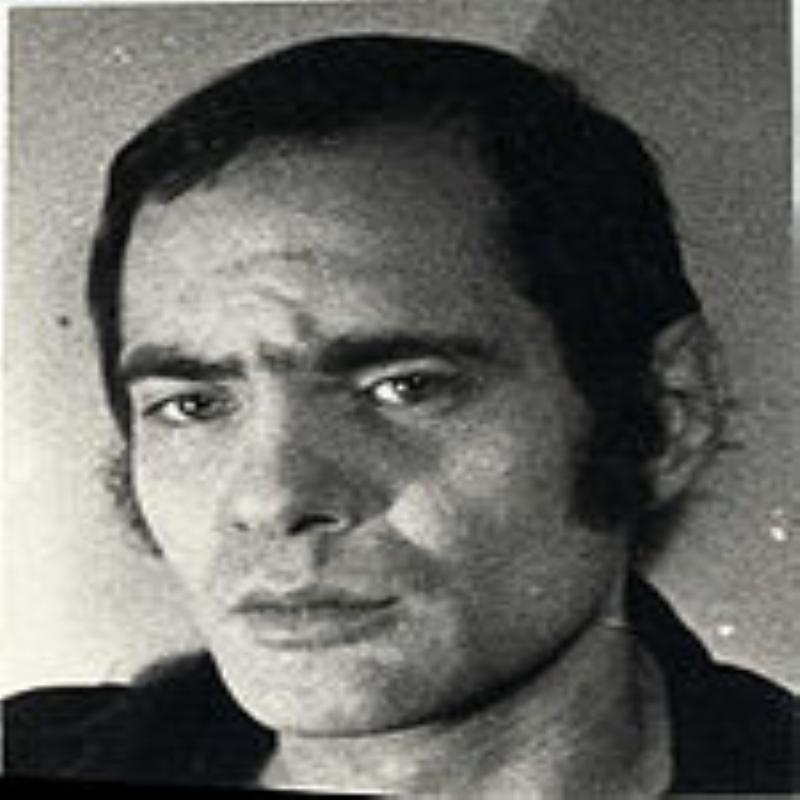

Andreas Baader who had been born in Munich on 6 May 1943, was a handsome and charismatic man, a school drop-out with a string of criminal convictions who lived on the fringes of society and was the only member of the Red Army Faction not to have received a university education. He had little interest in politics and even less empathy for his fellow man, but he was rebellious by nature and enjoyed the reputation of a renegade.

Gudrun Ensslin, who three years his senior was to become Andreas Baader’s lover was the daughter of a Pastor who had been a Girl Scout and did voluntary work in her father’s Church; but she had been raised to have a social conscience and to act on that conscience and it was during her time at Tubingen University that her conscience became political.

There she fell under the influence of Bernhard Vesper, a man of extreme political views both left and right by whom she was not just radicalised but had a son before ending the relationship with a phone call. She had fallen for the draft dodger and career criminal Andreas Baader.

In 1970, she, Andreas Baader, Ulrike Meinhof, and a colleague Horst Mahler formed the Rote Armee Fraktion, or Red Army Faction. They were in time to become better known as the Baader-Meinhof Gang, a media creation they never used.

Ulrike Meinhof’s elevated status in the public imagination was to become the cause of some resentment within the group especially as she was never a particularly effective urban guerrilla but her talent as a journalist was used to good effect and she authored many of their pamphlets and press releases.

She may have been thought a less than committed and somewhat lightweight terrorist as late-comers to a cause often are but then Baader, Ensslin and the others were already experienced terrorists long before the Red Army Faction was ever formed.

In April 1968 they had participated in a series of firebomb attacks on Department Stores in Frankfurt. Later arrested and convicted of arson they were sentenced to three years imprisonment but absconded when released pending appeal. Initially they fled abroad but soon returned to Germany where they went into hiding but Andreas Baader already well known to police and not a man to adopt a low-profile was soon apprehended driving a stolen car too fast, a speciality of his.

An elaborate plan to free him was now concocted that involved Ulrike Meinhoff who still then a journalist was not suspected, an interview and a book deal. A request was made to meet with Baader in a local library to discuss terms, remarkably it was agreed to.

In May 1970, as Baader’s guards were distracted Ensslin and three others burst in armed with pistols and released him shooting an elderly librarian in the process before escaping through a window. The brief shoot-out had excited Baader who feeling the entire incident reminiscent of John Dillinger or Jesse James remarked: “A gun certainly livens, things up a bit.”

On 22 October 1970, Ulrike blundered into a gun battle with police that ended in a fatality and an arrest which she only escaped by the skin of her teeth. She was shaken by the incident, a fact that she was unable to conceal.

In May 1971, they changed strategy from random acts of terror to specifically targeting United States Military Installations in Germany and in a series of bombings killed four American soldiers and injured 20 others. They also fire bombed and machine-gunned Government buildings which led to a series of gun battles with police that left several bystanders dead.

The Red Army Factions reign of terror was to be short-lived however, at least in its initial phase as the entire German State Apparatus along with foreign Intelligence Agencies, and Interpol combined in a massive manhunt which using of informants and undercover agents resulted in the arrest of Meinhof, Baader, Ensslin and most of the rest of the leadership of the group such as Horst Mahler, Holger Meins, and Jan-Carl Raspe.

There was some sympathy particularly among the young for the Red Army Faction hunted as they were by people many of whom had held similar positions of authority in a Nazi regime guilty of far greater crimes for which they had never been punished, if less so for the brand of authoritarian Marxist-Leninist politics they espoused. But it was also height of the Cold War and with Germany once again the most likely arena for any conflict between East and West nerves were stretched to the maximum.

The trial of these children of privilege who had acted out of conviction rather than need or hardship was to become a feature of the 1970’s and 80’s echoed in other places such as Italy with the Red Brigades.

Ulrike Meinhoff epitomised just such a person or so it was propagated, a bored and spoiled young woman with a flourishing career who turned to terrorism for the excitement and the thrill of the chase who was in truth a poor ideologue and so little thought of by the rest of the group she had been effectively excluded from the decision making process. Whether this was true or not she had been singled out for black propaganda designed to end once and for all any notions of Baader-Meinhof as a latter-day Bonnie and Clyde.

Meinhoff, Baader, and Ensslin along with the others were jailed in the recently built high security Stammheim Prison near Stuttgart where they were kept in isolation, denied reading material, kept under constant surveillance and some say not just emotionally but physically brutalised. In response to their harsh treatment, they went on collective hunger strike and were force fed. Even so, on 9 November 1974, Holger Meins died of starvation.

The trial of the leading members of the Red Army Faction began after considerable delay on 21 May 1975, amid tight security and before the eyes of the world with Ulrike Meinhof appearing subdued and Gudrun Ensslin nervous while Andreas Baader revelled in his moment in the spotlight.

In the meantime, on 24 April 1975, the German Embassy in Stockholm was seized by members of the Red Army Faction still at large who demanded the release of their comrades, but the Chancellor Helmut Schmidt refused to negotiate resulting in the death of two hostages.

Ulrike Meinhof did not live to see the conclusion of her trial, she was found dead in her prison cell on 9 May 1976, hanging from an improvised noose made of knotted together bath towels. The verdict was that suffering from depression as a result of being ostracised by her comrades she had taken her own life. It wasn’t widely believed, and Gudrun Ensslin later informed her lawyers that she did not wish to be ‘suicided’ like Ulrike and that if she were found dead in similar circumstances then it would be murder.

On 7 April 1977, Federal Prosecutor Siegfried Buback, an ex-Nazi Party member who had been harsh in his condemnation of Baader-Meinhoff was killed along with two of his bodyguards. It made no difference to the outcome of the trial which on 28 April saw Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin and the others sentenced to life imprisonment plus 15 years.

Despite their convictions in what was to become known as the German Autumn attempts to secure their release continued.

On 30 July, Jurgen Ponto, Chief Executive of the Dresdner Bank was shot and killed outside his home, but the most notorious incident occurred on 5 September when the leading industrialist Hanns-Martin Schleyer was kidnapped.

Schleyer, who had previously not just been a member of the Nazi Party, but an SS Officer was one of the most powerful and influential men in post-war Germany and a personal friend of Chancellor Helmuth Schmidt and seemed to epitomise not just to the Red Army Faction but many others besides everything that was wrong with German society.

He was an obvious target for terrorists but the security measures taken to protect him proved inadequate when his Mercedes car was forced to break suddenly to avoid a baby buggy that had appeared in its path causing the cars of his security detail to ram one another; as horns blazed and people struggled dazed and confused from the vehicles five masked gunmen emerged from the shadows and sprayed them with machine gun fire, two policemen and Schleyer’s chauffeur were killed but the industrialist survived to be taken hostage.

On 13 October, a Lufthansa flight from Palma de Mallorca to Frankfurt was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine who in solidarity with their revolutionary comrades demanded the release of all Red Army Faction and PFLP members then in prison in Germany. But the Government remained obdurate in its refusal to negotiate with terrorists even after the captain of the plane was murdered.

Flown to Mogadishu in Somalia on 18 October the plane was stormed by the elite forces of German counter-terrorism and the hijackers killed.

It was later suggested that it was news of the PFLP’s failed attempt to secure their release heard on a stolen transistor radio that triggered the events which followed as that same day, Gudrun Ensslin, Andreas Baader, and Jan-Carl Raspe were discovered dead in their cells.

The official verdict was they had taken their own lives having earlier agreed upon a collective suicide pact following all attempts to strong arm the Government into releasing them had failed. But the circumstances of their death remain suspicious.

Gudrun Ensslin was found hanging in her cell in the manner of Ulrike Meinhoff, throttled not with bath towels but a far more lethal wire flex despite having earlier declared that she would never take her own life.

Andreas Baader was supposedly in possession of a gun that had been smuggled into the prison but rather than try and escape with it as would have been in character for a man who saw himself as a romantic hero, he instead put it to the back of his neck, not an easy thing to do, and shoot himself. In fact, multiple shots were later found to have been fired in his cell but whether he had been responsible for them remains a matter of conjecture. He certainly had powder burns on his hand, his right hand – but why, when he was left-handed.

Likewise, no powder burns were found at all on the hands of Jan-Carl Raspe who had also supposedly shot himself with a gun.

Another of the terrorists Irmgard Moller who was discovered unconscious in her cell suffering from multiple stab wounds but little recollection as to how she received them. She would later deny there had been any suicide pact.

Silenced once and for all their ‘suicides’ can be seen as a final statement of defiance, but their deaths were also convenient to the Authorities for they could no longer be a cause celebre nor a reason for repeat terrorism, while any information they may have had regarding complicity on the part of the Intelligence Services in their activities also died with them.

All conspiracy germinates in the fertile soil of convenience, after all.

The same day that the events at Stammheim Prison were reported to the press the bullet-riddled body of Hanns-Martin Schleyer was discovered in the boot of an abandoned car on the Belgium-German border. With it was a note: “After 43 days we have ended Hanns-Martin Schleyer’s corrupt and pitiful existence. His death is meaningless to our pain and rage.”

The Red Army Faction’s Second Generation’ as they became known continued for a time, but their attacks became less frequent and increasingly ineffective. On 20 April 1998, in a long communiqué issued to the press they announced their disbandment.

The Red Army Faction was one of several terrorist organisations operating on the European Continent throughout the 1970’s and 80’s who neither sought nor acquired popular support, and even at its peak rarely it had more than 40 members or known associates. Even so it had been responsible for hundreds of bombings, arson attacks, robberies, kidnappings and at least 34 confirmed deaths.

Ideologically inspired terrorism is a derivative of ideas not realities, Marxist theories dancing on the head of polemical pins debated and defined beyond endurance and indeed relevance resulting in the very acts of violence that both Marx and Lenin condemned as meaningless in the pursuit of class struggle and the establishment of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.

The nature of terrorism has since changed from the days of left-wing ideologues intellectualising ideas into specifically targeted acts of violence which to us now can seem almost romantic compared to the unimaginably horrible mass-killings committed in the name of religion – the terror of ideas replaced by the violence of bloodlust and fantasy. Even if in truth all acts of terrorism are political.

But the Red Army Faction could be no less ruthless.

Andreas Baader had declared that once the commitment had been made no member of the group could leave. When 21-year-old Ingeborg Barz witnessed a policeman killed during a bank raid she made a tearful telephone call to her mother begging to be allowed to return home. Her decomposed body was later found dumped by the roadside.

In the end the Revolution eats its own children.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: