Battle of Britain: The Few

Posted on 8th February 2021

On the night of 4 June 1940, as darkness descended the last of the British Expeditionary Force were evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk. A little over two weeks later, on 16 June, with the French seeking an armistice Prime Minister Winston Churchill addressed the House of Commons in a speech that was later broadcast to the British people:

What General Weygand has called The Battle of France is over. The battle of Britain is about to begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilisation. Upon it depends our own British life and the long continuity of our institutions and our Empire. The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us. Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands. But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of a perverted science. Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say – this was their finest hour!

Yet despite its defiant tone Churchill’s words rang hollow to many.

The British Army’s successful evacuation from Dunkirk may have been a ‘Miracle of Deliverance’ but it was also an ignominious military defeat that had seen it flee in haste before a triumphant enemy abandoning most of its heavy equipment in the process – 445 tanks, numerous trucks and other vehicles, 2,427 artillery pieces, 75,000 tons of ammunition, and 162,000 tons of fuel destroyed, spiked, blown up and set alight. It left it bereft of the means to defend itself and for much of the summer of 1940 in the area of the south-coast where any German invasion could be expected there was barely a single armoured vehicle.

Against the German military juggernaut that had swept through the Low Countries and crushed its ancestral enemy France in just six weeks a chastened Britain now stood alone, and though she no longer posed a threat to German hegemony in Europe she remained a thorn in the side of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Regime but one it was believed could be easily plucked, and few disagreed.

Joseph Kennedy, the American Ambassador to the Court of St James in London reported to President Roosevelt that he expected Britain to capitulate before the end of the year, and there had been those within the Cabinet who sharing that opinion had sought to respond positively to German peace feelers – but the decision to fight on had already been made.

In a dramatic meeting of the full Cabinet on the evening of 28 May 1940, with the Dunkirk evacuation already underway, Churchill had addressed those present in almost Shakespearean tones: “I am convinced that every one of you would rise up and tear me down from my place if I were for one moment to contemplate parley or surrender. If this long Island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each one of us is choking in his own blood upon the ground.”

Churchill had rallied the Government, as he would later rally the people, but few believed that Britain was anything but a country at bay – it would fight hard for its national survival no doubt but the outcome of that fight lay very much in the balance and the scales were not weighted in its favour. On 16 July, Hitler issued Fuhrer Directive No 16: “As England, in spite of her hopeless military situation, still shows no sign of willingness to come to terms, I have decided to prepare, and if necessary to carry out, a landing against her.”

It began the preparation for Operation Sea Lion – the invasion of England.

But it was never going to be as simple or straight-forward as it at first appeared.

Commanded by Field-Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt the plan was for an initial wave of 70,000 troops to land on a narrow stretch of coast between Brighton and Folkestone supported by an Airborne Division capturing key installations while also defending its flanks.

Once the beachhead had been secured Army Group A, some 350,000 men supported by 650 tanks and a similar number of armoured vehicles would be landed and advance towards the Thames Estuary. In the meantime, the Isle of Wight would be seized and a second landing take place in the West at Lyme Regis which after capturing Bristol would advance from the East to link up with Army Group A sealing off London and securing the south-east before a period of consolidation.

But the German High Command was divided over the practicality of the plan with the Navy regarding it as too ambitious and the Army believing necessary for its success a victory both swift and comprehensive.

Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, in command of the Kriegsmarine did not believe he had the resources to protect such an enormous invasion flotilla even with the extensive use of mines to seal off the approaches to the beachheads and the mobilisation of his U-Boats; for despite much of the Royal Navy being engaged elsewhere protecting sea-lanes and its Empire the Home Fleet still remained formidable and would surely wreak havoc with any invasion fleet in the close confines of the English Channel. The Commander of the U-Boat Fleet, Admiral Karl Doenitz also feared for its safety vulnerable as they were to attack from the air. Also, the invasion flotilla of some 2,400 barges gathered at assembly points in Calais, Cherbourg, Le Havre, and Boulogne would be vulnerable not only to naval attack but to aerial bombardment by planes of the Royal Air Force.

Von Rundstedt and Raeder argued furiously over the issue of a broad or narrow front invasion, but they did agree on one thing – there could be no invasion until Germany had secured air superiority.

In command of the Luftwaffe was the avuncular, charismatic, but vainglorious Reichsmarschal Herman Goering. Second only to Hitler in the Nazi hierarchy he was not a man given to introspection or self-doubt and firmly believed that, despite its earlier failure at Dunkirk, his planes could not only sweep the Royal Air Force from the skies but force Britain to the negotiating table before any invasion need even be contemplated. In this he was certain, and as the much-decorated fighter ace from World War One who had taken command of the famous Richtofen Squadron following the Red Baron’s death he knew what he was talking about and would not be argued with – his word was final.

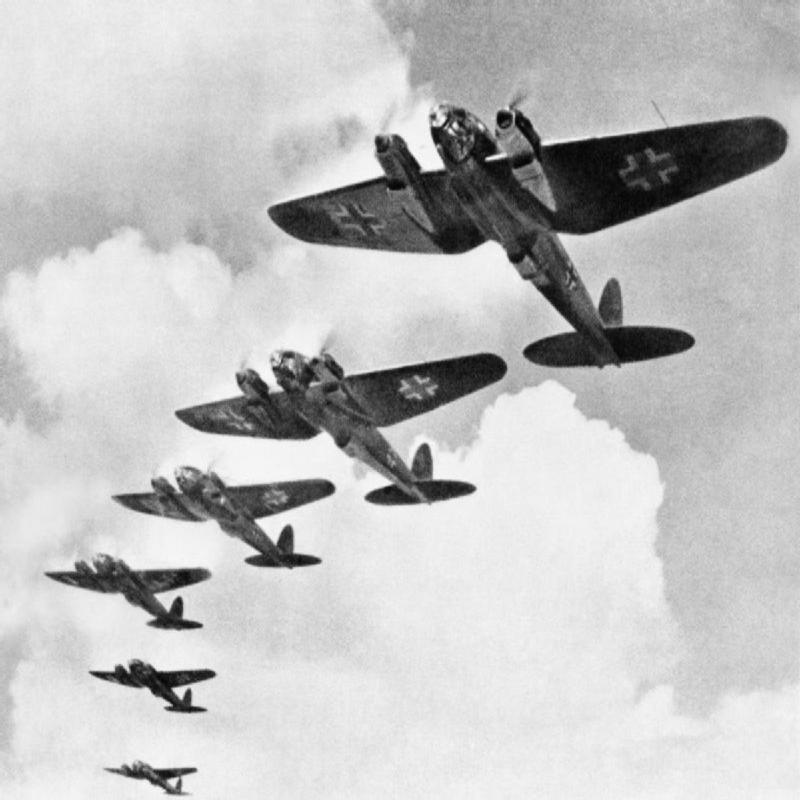

The Luftwaffe had a strength of 4,500 planes and would initially deploy 1,600 Bombers and 1,100 Fighters to the Battle of Britain divided between three Air Fleets – Luftlotte 2 under Albert Kesselring based in Belgium and responsible for London and the South-East; Luftlotte 3 under Hugo Sperrle and responsible for Wales, the West Country, and the Midlands; and Luftlotte 5 under Hans-Jurgen Stumpff based in Stavanger, Norway and responsible for Scotland and the North.

The primary German attack force would consist of medium and high-level Bombers the Heinkel III and Dornier 17, along with the dive-bombing capacity of the Junkers 88, or Stuka, which with its terrifying siren had become synonymous with the Blitzkrieg. They would be protected by the Messerschmitt 110, the first long-range fighter escort, and the more familiar Messerschmitt 109.

The Royal Air Force could call upon some 9,000 pilots but most were in Bomber Command and only around 20% were trained to fly fighter planes and even fewer had any experience of aerial combat. They would be divided into four groups – 10 Group under the command of Sir Christopher Quintin-Brand responsible for Wales and the South-West; 11 Group under the command of the New Zealander Air Vice- Marshal Keith Park that would patrol London, the South-East, and would bear the brunt of the battle; 12 Group under Air Vice-Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory responsible for the Midlands; and 13 Group under Air Vice-Marshal Richard Saul responsible for the North and Scotland.

The Luftwaffe had the planes, they had the air crew, they were experienced and moreover they were supremely confident. But the British had radar, the air-raid early warning detection device that had been devised by Robert Watson-Watt and successfully tested during the Daventry Experiment of February 1935.

By 1940, 19 Radar Installations were in place along the south and east coast of England that could detect incoming aircraft, track their flight path, and determine their likely destination; and known as the ‘Dowding System’ a structure was in place to utilise them with the data from the Radar Observation Posts sent to Fighter Command Headquarters at Bentley Park for interpretation and then onto the various Sector Stations from where the Squadrons would be scrambled to intercept incoming German formations.

The information was relayed by telephone cables buried deep underground with any gaps in radars effectiveness, such as that caused by low-flying aircraft covered by members of the Royal Observation Corps posted as lookouts – it constituted a fully integrated defence system.

The Head of Fighter Command since July 1936 had been Air Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, a prickly, dour, humourless but grimly determined man known without affection as ‘Stuffy’ Dowding who regularly clashed with both his superiors and those under his command.

He had long doubted the Air Forces capacity to defend the country in a time of war and as Head of Research had initiated the competition to design a fast single-wing fighter to replace the increasingly obsolete bi-plane. What emerged were the Hurricane which went into production in June 1936 and the Spitfire introduced in August 1938 – small, fast, and manoeuvrable it would be these two planes that would carry the burden for most of the fighting during the Battle of Britain. He had also closely observed the rise and performance of the Luftwaffe and had been concerned enough to advise the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to pursue a policy of appeasement to buy Fighter Command more time for strategic planning, the training of pilots, and the production of planes.

Considered unimaginative and over-cautious Dowding had been under pressure ever since the invasion of France in May 1940, when Fighter Command was criticised, somewhat unfairly, for failing to protect the troops on the beaches at Dunkirk and he personally for not committing his full force to doing so. Now he clashed with Churchill for refusing to send his fighter squadrons back to France in strength to participate in a battle he believed was a foregone conclusion and having already lost 425 pilots in aerial combat, and later 800 experienced ground crew in the Lancastria disaster he felt any further unnecessary sacrifice would seriously imperil Fighter Command’s ability to defend the skies over Britain in the battle he knew was to come. And he did not shy away from telling Churchill so insisting that with only 500 serviceable planes and even fewer trained pilots he would not be able to guarantee air superiority for more than 48 hours.

The phlegmatic and obdurate Dowding was not easily dissuaded from a course of action and certainly not by heroic gestures towards an erstwhile ally bent on its own destruction, and with Cabinet support he won the argument. For him the preservation of Fighter Command outweighed all other issues, and it dominated his every thought and deed.

Although German incursions into British air space had been occurring for some time the Battle of Britain could be said to have started on 10 June with air raids on the Channel ports and Stuka Dive Bomber attacks on convoys.

It was a matter of national prestige that British ships should not be forced from their own home waters and Dowding was ordered to defend them, but he was reluctant to commit fighters to convoy protection when many of the ships were simply sailing from other British ports and carrying goods, mostly coal, that could easily be transported by other means, or indeed by night. So, protect them he did but with as few planes as possible and in the fighting over the Channel the R.A.F was regularly outnumbered three to one.

Despite sinking more than 30 ships in little over a month the attack on the convoys had proved a disappointment for its real intention had never to seriously disrupt Britain’s sea traffic but to force Fighter Command to commit to an all-out confrontation. Instead, Dowding’s refusal to commit more than the minimal required response saw 316 German planes lost in six weeks of fighting to just 200 British. The frequent and deliberately provocative sweeps over the south-east by German fighter planes had also not forced Dowding’s hand. But a change in strategy was already underway.

Operation Eagle would target not just the Ports where valuable supplies were stored but also the Airfields and Sector Stations which Fighter Command would be compelled to defend, drawn into combat with the escorting Messerschmitt 109’s and 110’s they would then be overwhelmed and destroyed. But Dowding had no intention of engaging in an aerial battle and Squadrons would continue to be scrambled according to need only. They also had strict orders to focus on the Bomber Formations and avoid contact with the Fighter Escort where possible.

The Eagle Offensive began the following day with a mass-bombing raid on Southampton and Portland. At the same time 77 Stukas attacked the Sector Station at Middle Wallop but the failure to destroy the Radar Masts the previous day saw them intercepted and 9 were shot down with many more seriously damaged.

The Luftwaffe had more success at Detling Airfield where the hangars and operational room were destroyed, and 67 Ground Crew and Women’s Auxillary Air Force were killed. On 12 August, the Luftwaffe attacked the Radar Stations at Rye, Pevensey, Ventnor, Dunkirk, and Dover. Well camouflaged and well defended they were difficult to locate and only at Ventnor were the Radar Masts hit and any serious damage done.

The attack on the Radar Stations had cost the Luftwaffe 27 planes shot down but initially at least they believed they had irreparably damaged British communications, but such optimism would soon be dispelled. An intended attack upon Rochester was intercepted and after an intensive aerial engagement was forced to withdraw without ever reaching its destination.

Eagle Day had proved far from an overwhelming success for despite damaging the coastal ports and some secondary targets it had cost the Luftwaffe 48 planes for only half as many British and had done little to diminish Fighter Commands effectiveness. But it was to be just the beginning of a prolonged offensive. Indeed, it was to be a battle of attrition with strains and stresses little different to those experienced by the troops in the trenches of the Western Front during the First World War, even if the image it conveyed could not have been more dissimilar.

A Fighter Pilot was on average just 20 years of age, many of them had been promoted from the Auxiliary Air Force where a large number had paid for the training out of their own pockets and indeed 601 Squadron based near London had so many aristocrats in its ranks they were known as – The Millionaires. But there were also many working-class pilots who had either been Cadets before the war or were recruited from Ground Crew and though it was assumed that a Fighter Pilot was an Officer these rarely rose above the rank of Sergeant and so were paid less.

The rigid class structure of pre-war Britain was amply reflected in the make-up of its Armed Forces and there was no little snobbery within Fighter Command, and some at least would come to deeply resent the term ‘Brylcreem Boy.’

But the image of Fighter Command was a glamorous one in large part due to its many wealthy and aristocratic flyers and the single-combat nature of the warfare, but it wasn’t so much dash and fire as endurance that would be the order of the day.

Dressed in full flying kit many hours would be passed just waiting, – reading paperbacks, doing crossword puzzles, kicking a ball about. Pets were popular as a distraction as also was music and the radio but all the time, they knew that at any moment the call to scramble would thrust them into a life and death struggle not just once but maybe two or three times a day.

They also knew that everything hinged on them, that it was a national struggle for survival the outcome of which depended on their success or failure. Few were unaware of the gravity of the situation and often the strain was almost intolerable. As a consequence, the night time partying could be boisterous but rarely without a sense of loss and the feeling that they had been the lucky ones. Indeed, so few were they in number that every death took on the aspect of a personal trauma. But for the people watching the dogfights in the skies over the Weald of Kent, London, and the south-coast the sense of excitement was palpable, and children in particular would remember for years to come the sound of the engines, the sight of the tracers, and though they rarely knew which was which it never entered their mind that a downed plane was anything but a German one.

But the battle had yet barely begun. On 15 August, all three Luftlotten attacked simultaneously.

With the Royal Air Force focussing its attention on the South where any invasion was expected German Military Intelligence, already confidently predicting that Fighter Command was down to its last 300 serviceable planes, had informed Goering that Scotland and the North of England depleted of resources would be largely undefended. It presented, or so it seemed, the perfect opportunity to show that the Luftwaffe could strike anywhere on the British mainland and at any time unmolested and without fear. They were soon proved in error.

General Stumpff, in command of Luftlotte 5, sent 17 Seaplanes across the North Sea to draw what Fighter squadrons were available away from the main Bomber Formations. The decoy worked but a breakdown in communication saw the Bombers take the same flight path and in the ensuing dogfight they were badly mauled losing 14 Bombers and 7 Fighters, or 20% of their total strength. Luftlotte 5 would make no further daylight raids and most of its Fighters were transferred to the other Air Fleets.

In the South and West however, they were more successful.

The Airfields at Hawkinge and Eastchurch were hit and that at Martlesham Heath put out of action. The Sector Station at Middle Wallop was also struck several times but continued to operate whilst those at Kenley and Biggin Hill were missed altogether.

Goering was to maintain the pressure and over the next three days the Airfields at Odiham and Worthy Down were both seriously damaged and the Sector Stations missed in the earlier attacks, along with that at Tangmere, were hit.

On 18 August, the intensity of the aerial combat increased to a level never witnessed before and more planes were to be lost on what became known as ‘The Hardest Day’ than at any other time during the battle as some 71 German planes were shot down with many more badly damaged at the cost of just 29 British Fighters. More significantly, the Luftwaffe had lost 94 valuable Air Crew killed and a further 40 captured after bailing out.

Despite fighting all day with Squadrons scrambled, returning to Airfields often already under bombardment simply to refuel then take off again, Fighter Command had lost just 10 men killed, and could breathe a huge sigh of relief that only 3 of these had been pilots.

Dowding’s policy of carefully harnessing his resources and targeting the Bomber Formations appeared to be paying off at least in numbers lost but it had proved incapable of preventing the Luftwaffe from reigning freely in the skies over Britain, or so it appeared. And the bombing raids continued: on 24 August North Weald and Hornchurch were hit; on 26 August Debden; on 30 August Biggin Hill was struck twice; on 31 August Debden, Detling, Hornchurch, Croydon, and Biggin Hill were all hit. If Fighter Command scrambled to intercept then the Luftwaffe would change course to attack lesser Airfields such as Manston, Eastchurch, Lymn, and Rochford.

Wave after wave of Bombers attacked the Airfields and Sector Stations for 14 consecutive days and the pressure was so intense that squadrons would be scrambled sometimes three or four times a day; and with most of the Airfields damaged, runways cratered, hangars destroyed, and many Sector Stations only partially operable the coordinated response to the near constant attacks began to break down. It was now that a furious row broke out in Fighter Command over tactics.

The Commander of 12 Group, Trafford Leigh-Mallory, criticised Dowding’s piecemeal response to the battle believing that the failure to prevent the air raids risked Fighter Command being defeated not in the air but on the ground. He wanted to adopt Big-Wing formations of numerous squadrons to challenge the Fighter Escorts preferably over the Channel before they reached Britain but though more effective in combat it was argued that the Big-Wing formations took too long to form up and would fail to intercept the German Bombers as they came in. Leigh-Mallory was to take the argument all the way to Churchill himself and with the support of Britain’s most famous Fighter Ace Douglas Bader, demand Dowding’s removal. But Dowding still had the confidence of Keith Park whose 11 Group were bearing the brunt of the fighting and with his support he survived but his authority had been undermined and Leigh-Mallory would adopt Big-Wing tactics regardless.

It was an argument that Dowding could have done without for no one was feeling the pressure more than he and it was often remarked just how exhausted he looked; and nothing troubled him more than the lack of pilots – he could replace the lost planes with more than 300 being manufactured every week, but not the pilots and with never more than 1,400 available to him every one lost was a stab to the heart of Fighter Command and its ability to sustain the struggle. In mid-August, 50 pilots were transferred to Fighter Command from the Fleet Air Arm, but they had little, if any, knowledge of the kind of aerial combat required whilst others used to fill the thinning ranks were leaving Training Schools with barely 9 hours flying experience.

Yet he continued to resist demands that he use the Czech and Polish pilots he had at his disposal few of whom spoke any English and it was reported would not maintain radio silence, deliberately or otherwise refused to fly in formation, and generally disobeyed orders.

They would by their reckless behaviour, he believed, undermine the command structure and endanger the entire operation. But they were good pilots, well-trained in their home countries and highly motivated to get at the Germans. Now, at last, he had little choice but to give way, and the contribution of pilots from overseas, not just Czechs and Poles, but those from the Commonwealth countries and others such as France, Belgium, and the United States cannot be underestimated. Even so, resources in manpower remained scant and Dowding’s constant fear was that just one bad day could turn the tide of the battle - but the Luftwaffe too was feeling the pressure.

On 19 August, Goering ordered that the Stuka be withdrawn from the battle. It had proved too vulnerable to attack and its losses were unacceptably high including 30 shot down or damaged beyond repair on a single day.

The much-vaunted Messerschmitt 110 had also been shown to be slow and cumbersome and easy prey to the Spitfire with 79 lost in a single week. Escort duties would now be the sole responsibility of the Messerschmitt 109’s but with only fuel enough to remain over Britain for 30 minutes it meant that the Bombers would have to return without Fighter support. He also ordered that there should be three Fighters for every Bomber and that they were to provide close quarter escort which impeded their combat effectiveness but also made it more difficult for the R.A.F to penetrate the Bomber Formations protective screen.

The same day he also made his first strategic mistake of the campaign when he ordered the Luftwaffe to cease its attacks upon the Radar Stations, they had proved too costly in both men and machinery and had done little he believed to diminish Fighter Commands capability. But no number of tactical and strategic changes could restore the confidence of Air Crew whose morale had been badly shaken by their perceived failure.

Pushed to the limits of endurance to fulfil the positive outcome that not only Hermann Goering but the Fuhrer demanded and told time and again that the British had few planes left and were close to breaking point they had seen their losses mount day after day, week after week with the prospect of victory no nearer - it was a bitter struggle.

The Luftwaffe had a very effective system of air-sea rescue, the Notdienst Unit, 30 Heinkel Floatplanes assigned to pick up air crew forced to ditch in the Channel and the North Sea. So effective was it that on 13 July, Fighter Command was ordered to shoot down these air ambulances even though they rescued British as well as their own pilots. There could be no mercy for those Germans forced to ditch in the sea so they would now be left to drown or freeze to death in the icy cold waters – Luftwaffe airmen could not be permitted to survive merely to return and bomb British cities, and their losses continued to mount.

Goering now increased the night-time raids on British factories and on the advice of Kesselring intensified the bombing of the Airfields. Dowding’s pessimism mounted as he lost more and more veteran pilots and their replacements were raw recruits with little or no combat experience who often proved more of a danger to their colleagues than they did the enemy, and he could only guess at the Luftwaffe’s resources – Fighter Command was at its lowest ebb. But now Goering made his second strategic error of the campaign.

On 7 September, with the support of Kesselring, Goering sent 300 Bombers with escorts to attack London in the first large-scale daylight raid on the city. Fighter Command believing they were once again heading towards the Airfields were scrambled to meet them.

The aerial combat that followed was as fierce as ever, but Fighter Command breathed a huge sigh of relief – at last, the pressure on the Airfields had relented and they were able to reorganise and rebuild. Dowding was later to refer to it as a miracle.

But Goering, and in particular the Fuhrer were delighted. Hitler, whose mind always inclined towards terror as a tactic been outraged by the R.A. F’s 24 August bombing raid on Berlin. Now he had vengeance.

Goering, who having received reports that most of the Airfields had been put out of action and that Fighter Command was down to its last 150 planes believed the mass-bombing of London would prove the final straw. The same day the Germans bombed London the Government issued a warning that invasion was imminent and ordered Bomber Command to attack the French Channel ports where the invasion barges were moored and 214 were destroyed, or 10% of the total.

Accounts of the air raids on London indicated to Luftwaffe High Command that not only had Fighter Command been slow to react but had also been less vigorous in its response appearing to bear out the constant stream of positive reports emanating from German Military Intelligence of destroyed Airfields, broken communications, high casualties, few planes, and low morale. One final push, an all-out effort, would decide the issue.

On 15 September, in the most sustained bombardment yet, 600 Heinkel and Dornier Bombers escorted by 650 Messerschmitt 109’s set off in two waves for London. Perhaps sensing it was the defining moment Dowding scrambled Fighter Command in force with both Park’s 11 Group and Leigh-Mallory’s 12 Group, adopting the Big-Wing formation, engaging the German Bombers as they came in. The fighting was fierce continuing all day and for much of the night and though Fighter Command could not prevent the Germans from dropping their bombs they took a heavy toll.

The Luftwaffe in their turn, believing Fighter Command was all but finished, were astonished by the resistance they met and by the end of a brutal day 59 German planes had been shot down and 20 so badly damaged they were forced to crash land. They had also lost 102 men killed and 65 captured. The British had lost 29 planes shot down and 14 pilots killed.

Although the German losses were later exaggerated for public consumption there could be little doubt that it had been a great British victory and it quickly became apparent to the Luftwaffe that for all the planes lost, men killed, and always over- optimistic intelligence reports that they were no closer to defeating Fighter Command and gaining air superiority than they had been at the beginning of the campaign.

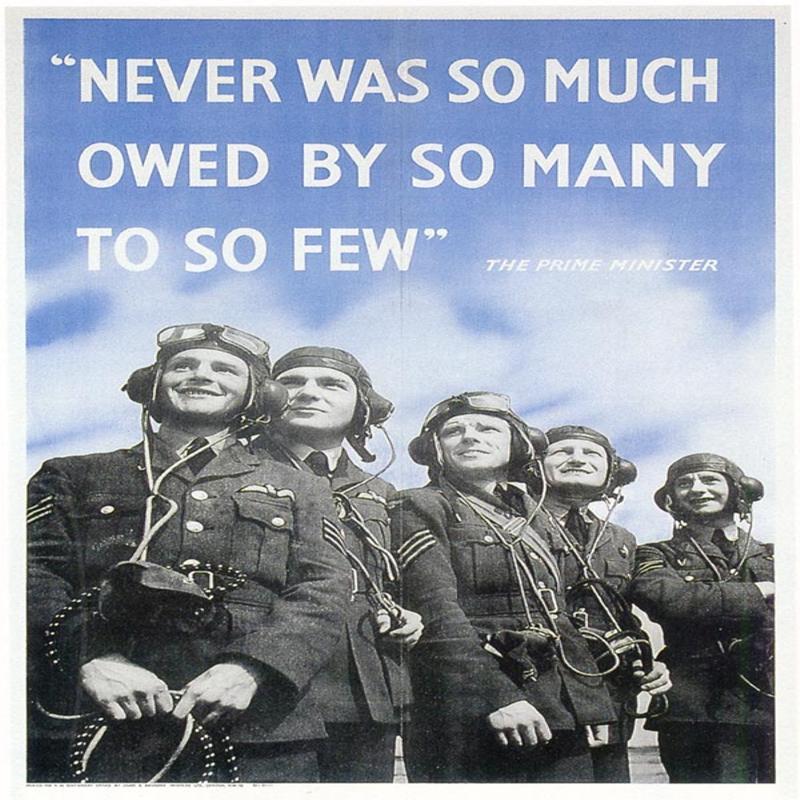

Earlier on 20 August, when the fighting was at its most intense and the outcome remained very much in the balance Winston Churchill had addressed the House of Commons:

The gratitude of every home in our Island, in our Empire, and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to the British airmen who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of the World War by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.

In three months of sustained aerial combat the Luftwaffe had lost 1,887 aircraft to enemy action with 2,698 Air Crew killed and 967 taken prisoner.

Fighter Command lost 1,547 aircraft, and of the 2,935 R.A.F pilots who participated at some time or other during the battle 544 were killed (of whom 98 were foreign nationals) and 422 wounded.

A further 814 of ‘The Few’ would die before the end of the war.

Both the Reichmarschall and Fuhrer were frustrated at the outcome but remained firm in their belief that in terror lay the key to victory.

The Battle of Britain was over, the Blitz was about to begin.

Share this post: