Battle of Lepanto

Posted on 4th March 2021

The onset of the Reformation and the religious schism that ensued divided and seriously weakened a once unified Christendom leaving it vulnerable to the ambitions of an insurgent Islam; a previous attempt by them to seize control of the Eastern Mediterranean and secure a base from which to invade Southern Europe had been thwarted by their failure to capture Malta in 1565; but this was to prove a temporary setback only, and five years later the Ottoman Empire would try again this time with an attack upon the island of Cyprus.

A possession of Venice since 1489 and a mere 250 miles or so from the southern shore of Turkey, Cyprus’s strategic significance could not be ignored. It dominated the trade routes of the Levant and having grown rich as a result its capture would greatly reduce Venetian influence in the region and immeasurably increase the coffers of the Ottoman treasury - it was then, a mature fruit ripe for plucking.

The campaign against Cyprus should have come as no surprise to its defenders but when In June 1570 an Ottoman Fleet of 400 ships carrying 200,000 men was sighted offshore it did, and it created panic for little preparation had been made to resist a siege and so behind poorly manned and dilapidated fortifications one town after another fell until by September the conquest of the island was almost complete. Only the city of Famagusta remained to be subdued.

Yet despite overwhelming odds and no prospect of relief the city’s Venetian Commander Marcantonio Bragadin refused to surrender and his garrison of only 8,500 Italian and Cypriot troops were to hold at bay the vastly superior forces of the Ottoman Turks for eleven long months.

It was a defiance that earned the defenders little respect from the Ottoman Commander Kara Mustafa who had seen his reputation reduced to that of an incompetent braggart whose repeated declarations of victory had proven hollow. Finally on 5 September 1571 with their fortifications breached and his garrison reduced to fewer than a thousand ragged and exhausted men Bragadin agreed to surrender but he would only do so under terms.

Such had been his humiliation Mustafa professed a willingness to negotiate, anything to bring the conflict to an end, and the terms he offered were generous.

The Ottoman Commander agreed an honourable surrender in which the defenders were promised their liberty and a safe passage to Crete, but no sooner had they laid down their arms than their Senior Officers were brought before him and accused of a series of crimes among them the massacre of Turkish prisoners. Bragadin declared any such charges to be false and accused Kara Mustafa of cowardice, deceit and of acting in bad faith. In a rage, Mustafa ordered the Venetian’s ears and nose be cut off and the Officers who had accompanied him to be beheaded before his eyes. Before he was thrown into a windowless dungeon where with his wounds allowed to fester and fed barely enough to keep him alive, he was regularly beaten and deprived of sleep. In the meantime, those Christians remaining in the city were put to the sword while the troops who having surrendered had been promised their freedom were instead delivered into slavery and chained to the oars of Turkish galleys.

Two weeks later Bragadin was taken from his dungeon his body weighed down by sacks of rocks and marched through the streets of Famagusta to the Ottoman Camp where, paraded before the troops he was forced to crawl to Kara Mustafa’s tent and made to eat dirt. Then taken to a ship moored offshore he was bound to a chair and hoisted up the yardarm from where his degradation could be witnessed for miles around. After some hours subjected to the searing heat of the afternoon sun he was hauled down and taken to the town square where stripped naked and tied to a pillar he was flayed alive.

Death must have come as a blessed relief to the abused Bragadin, but his humiliation did not cease with his passing; first his body was decapitated and quartered the various parts distributed among the Ottoman Army before his flayed skin was sewn back together, stuffed with straw, dressed in his military tunic and sent, along with the heads of his immediate subordinates, to the Sultan, 'Selim the Drunkard', in Istanbul as trophies of war.

Bragadin’s fate had been a horrible one, but his heroic defence of Famagusta had provided time, invaluable time for the Pope to form a Holy League to defend against further Islamic incursions into Christian Europe - to do so was easier said than done but Pius V was to prove the right man, in the right place, at the right time.

Unlike his predecessor in the Vatican, Pius V was a man of God who disavowed the pleasures of the flesh. He wore a hair shirt under his plain Dominican robes and frowned upon those who did not do likewise and life at St Peter’s ceased to be sumptuous; the food served was of simple fare, wine became sparse, and the Court Jester was dismissed. He passed his days on matters of state and his nights in deep reflection. He also took a keen interest in the activities of the Inquisition often attending interrogations and rarely missing an execution.

As Pope he worked hard to organise a unified Christian response to the threat posed by Islam but the diplomatic missions despatched to the Royal Courts of Europe to elicit support met with only limited success at best with both Portugal, concerned for the vulnerability of its lucrative slave outposts on the coast of West Africa, and France, which saw the Ottoman Empire as a potential ally in its ongoing struggle with Spain and the Habsburgs for mastery in Europe being notable absentees from what would be an entirely Catholic Coalition - the Protestant States of Northern Europe having decided to remain aloof from the fray uncertain as to who exactly was to be considered an ally and who a foe.

The Coalition that emerged was less than was hoped for, but it would suffice.

The treaty formalising the creation of the Holy League was signed in Rome on 24 May 1571, its signatories were: Spain, Venice, Genoa, Urbino, Tuscany, Savoy, the Knights of Malta, and the Papal States.

Immediately upon the ceremony’s conclusion Pope Pius appointed Admiral Marco Antonio Colonna to form a fleet under the Banner of the Cross.

Colonna may have had the responsibility for the formation of the Holy League’s Armada, but its command would fall to Don John of Austria, the illegitimate son of the previous Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and half-brother to Philip II of Spain, who despite his youth, he was 24 years of age, was an experienced naval officer and veteran of previous campaigns against the Ottomans.

As Spain financed the Holy League and provided it with most of its manpower and resources Pope Pius had little option but to comply with Philip II’s choice for its commander. Even so, old rivalries die hard even in moments of the greatest extremity and though Don John was well-qualified to command there were others within the Holy League who thought themselves better able to do so.

When Don John arrived to take command, he found many of the Venetian ships seriously undermanned and immediately ordered that Spanish troops make up the numbers but he had done so without first consulting Colonna. Furious that his authority had been undermined and in a fit of pique the Venetian Admiral had a Spanish Officer arrested on trumped up charges and hanged from the yardarm of his own ship. The row that ensued threatened to disrupt the cohesion of an always fragile coalition was eventually patched up, but the two men did not speak again for the entirety of the campaign.

Venice was the city most immediately threatened by Islamic aggression. It had long been a thorn in the side of the Ottoman Empire competing as it did for control for the Levantine trade routes and domination in the Eastern Mediterranean. It was on paper at least an unequal contest but what the Venetians lacked in manpower and resources they more than made up for in experience, invention and endeavour.

The confrontation when it came, they knew would be at sea and both the arms designer and shipbuilder Francesco Duodo along with Admiral Sebastiano Venier had been working closely together to improve the city’s capacity to wage such a war. In great secrecy they had designed and constructed the first Gallease which unlike the galleys of the day which rarely carried more than a gun at the front and perhaps two or three at the rear utilised the entire length of the vessel providing it with an immense armament of 40 guns or more. When galleys came alongside one another their guns were rendered useless but with a Gallease able to fire broadsides this was no longer the case. They had also been constructed with a heavier reinforced wood and had raised sides making them almost impossible to board, the Turks favoured tactic – Venice would then, be ready.

Spain, which would provide the largest contingent of troops and was still smarting from the annihilation of its mighty fleet at the Battle of Djerba ten years earlier, was also ready.

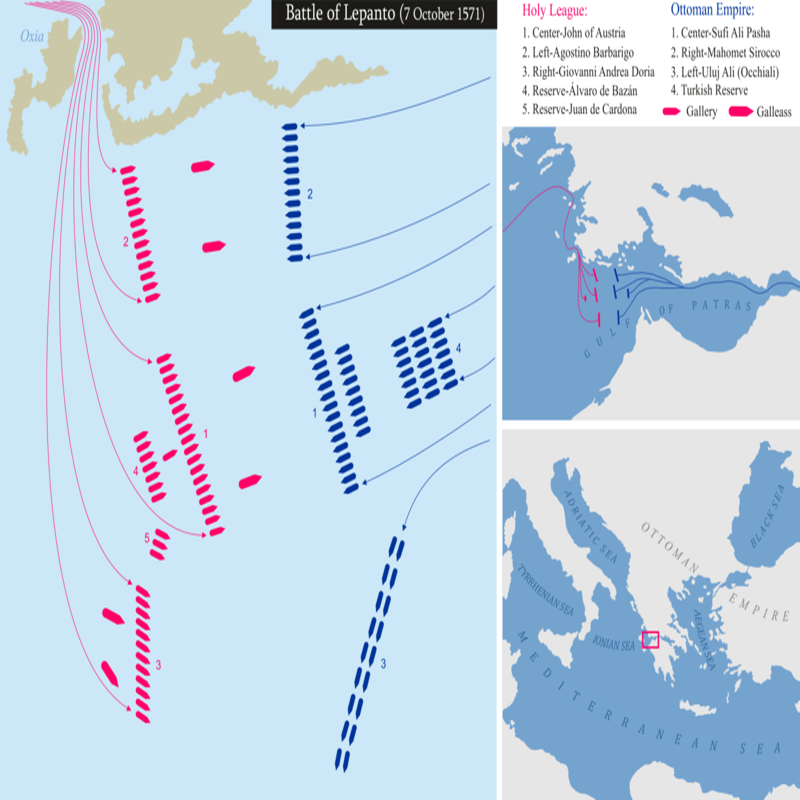

The Christian Fleet sailed from Messina in Sicily on 16 September 1570 through the Straits heading east to seek out and destroy the enemy. By 7 October it had reached the Gulf of Patros off the western coast of Greece where it sighted the Ottoman Fleet. An emergency War Council was immediately held where Don John decided to engage without delay – there was no dissent.

The same unity of command was not to be found in the Ottoman camp where the Fleet Commander Muezzinzade Ali Pasha, no less eager to fight was challenged by his subordinate Uluc Ali Pasha who thought it foolhardy to sail and engage with the enemy when they could remain where they were under the protection of the guns of the various fortresses that dotted the shoreline. Indeed, it might even be possible to lure the Christian Fleet further into the Gulf and destroy it piecemeal. Ali Pasha disagreed, not only would it be dishonourable to refuse battle once it had been offered but he had strict orders from the Sultan in Istanbul to meet with and destroy the enemy for the greater glory of Allah not hide away and allow it to destroy itself.

As the two fleets formed up on uncertain waters beneath a brooding sky and with a storm brewing, they did not appear to be evenly matched and nor were they. In both ships and manpower, the Ottoman Fleet was clearly the superior. It consisted of 278 ships (56 of which were Galiots, small, fast, and manoeuvrable vessels used for harassment and boarding) and 35,000 men.

The essential warship of its day and the one that made up the main component of both fleets was the galley, a vessel of slender construction some 120 feet long and in some places barely 6 feet wide with 25 benches of oars operated by 3 to 5 men on either side. On the Ottoman galleys these were for the most part Christians kidnapped from their homes, taken while at sea or captured in battle who had since been sold in the slave markets of North Africa. There were some 30,000 at the Battle of Lepanto and chained to their oars there was little chance of survival should their ships be sunk or set afire. With two large sails for long distance travel the galley could reach speeds of up to 12 knots and the optimum speed would be sought to fully utilise the ‘beak’ at the prow of the vessel intended to ram and snare the enemy in preparation for boarding. Its armament was often just one large gun sited at the front of the ship but with a great many anti-personnel weapons with which to clear the decks of enemy ships.

The Holy League had fewer ships just 212, with 115 provided by Venice, 49 by Spain, 27 from Genoa, 7 from the Papal States, 5 from Tuscany, and 3 each from Savoy, the Knights of Malta, and a further 3 licensed Privateers.

They were likewise outnumbered with just 28,000 troops – 7,000 Spanish, 6,000 Italian, 5,000 Venetian, 2,000 Croatian, 2,000 Slavs, and 6,000 sundry others. But they had many more guns 1,815, and among their ships were six of the new and formidable Galleases. Also their Spanish troops were among the finest in Europe and they were well equipped with helmets, breastplates, and many were arquebusiers while the Turks were perhaps over-reliant on bowmen whose arrows could often not penetrate the Spanish armour.

Much like the Ottoman Fleet their ships were powered by sail, oar, and slave.

A little before noon the two fleets formed up facing one another in a line stretching for four miles or more. It was important for Don John to get as close to the shoreline as possible to negate the Turks favoured tactic of developing a crescent like formation so as to be able outflank the enemy in a wide arc before enveloping them in a vice-like grip.

At the centre of the Christian line was Don John himself aboard his flagship the Real along with 61 other galleys. On the left nearest the shoreline was the Venetian Agostino Barbarigo with 53 galleys while commanding the right of the line was the Genoan Giovanni Andrea Doria. All three Divisions had 2 galleases at their forefront able to lead the charge and bring down a heavy fire.

Ali Pasha aboard his flagship the Sultana flying the Banner of the Caliphs, a huge green flag embroidered with text from the Qu’ran would confront Don John in the centre with 61 galleys and 32 galiots. On the right of the Ottoman line was the Barbary Corsair Mehmed Scirocco, a man of brutal and uneven temper with 57 galleys and 2 galiots while on the left was Uluc Ali Pasha with 61 galleys and 32 galiots. But whereas John Don had provided for a powerful Reserve of 39 galleys under the command of Alvaro de Bazin no such provision had been made on the Ottoman side, just a handful of undermanned galleys and sundry other craft – it was to prove significant.

Having formed up in order of battle with horns blaring and banners waving the commanders met with their subordinates, finalised their orders, and said their prayers. Don John had just completed a tour of his ships in an open boat exhorting their crews not to flinch from the task that lay ahead and boosting morale. Now from the prow of his flagship he delivered the message: “The time for talking is over, the time for fighting has come. There can be no paradise for cowards.”

Similar scenes were occurring in both fleets as decks were cleared, guns were primed, troops gathered, and Captain’s addressed their men. Perhaps with scant sincerity Ali Pasha promised all Christian galley slaves their freedom should they remain loyal. But for all the preparation and prayer complacency had been detected in the Ottoman camp. As one observer noted: “They all went into battle with the greatest yearning although we believed that the enemy fleet was much greater than our own. Due to their victories achieved in the past they thought little of our strength.”

If there was any complacency it soon dissipated as it became clear the two fleets were more evenly matched than at first appeared. In the centre of the line Ali Pasha, furious that he had not been made aware of the destructive power of the galleases, headed straight for Don John’s flagship seeking to kill his rival and end the battle early.

Picking up pace the Sultana rammed the Real with such force that the entire ship trembled and shook with many knocked from their feet and some thrown overboard, while the first four rows of galley slaves were killed outright; but the attempt to board was repulsed as elite Janissaries and Spanish infantry fought face-to-face and hand-to-hand. The struggle remained in the balance however, and had it not been for the timely intervention of Marcantonio Colonna who came alongside and boarded the Sultana it may have turned out very differently.

Outnumbered and attacked from both sides the Janissaries fought to the last man and among the killed was Muezzinzade Ali Pasha. Learning of the Emir’s death Don John ordered the body decapitated and his severed head placed upon a pole and paraded up and down the deck of his ship as the Banner of the Caliphs was lowered and that of the Holy League, raised in its place.

Elsewhere the two fleets converged with the galleases of the Holy League manoeuvring so as to bring their broadsides to bear taking a terrible toll of the lead Turkish galleys throwing them into disarray. The first ships to clash were those of Barbarigo and Scirocco nearest the shore and there was little time for seamanship or tactical genius as the two fleets rammed into each other at great speed seeking to ram and board. The ships being so tightly packed it was said that a man could simply step from one onto another. The author Miguel de Cervantes who fought at Lepanto losing the use of his right arm described the nature of such fighting in his epic novel Don Quixote:

“And yet, though he sees with a first heedless step he will go down to visit the profundities of Neptune’s bosom, still with dauntless heart the knight makes himself a target for all that musketry and struggles to cross the narrow path to the enemies ship.”

In a bitterly fought encounter that saw both Barbarigo and Scirocco killed, the former with an arrow to the eye, the latter beheaded on the deck of his own ship, the Holy League emerged triumphant but only just and largely as a result of freed galley slaves taking up arms and turning on their masters.

The death of Muezzinzade Ali Pasha and the lowering of the Banner of the Caliphs had greatly demoralised the entire Ottoman Fleet and as the battle turned against them those who were able to begin beaching and abandoning their ships just as Don John had suspected they might.

Triumphant both in the centre and on the left of the line the Holy League’s victory appeared all but assured but on the right the story was very different. Here Uluc Ali Pasha had forced Andrea Doria to sail out of position thereby creating a gap that exposed Colonna’s left flank. This was the opportunity and Uluc Ali Pasha was quick to seize it as his fleet descended in force upon 15 or so of the Holy Leagues galleys clustered around the flagship of the Knights of Malta. They were hard pressed, and it seemed for a moment that victory could still be snatched from the jaws of Ottoman defeat but it was now that the Christian Reserve Division would prove its worth. Frustrated at having to witness events from afar its commander Alvaro de Bazan did not hesitate to act but there was little fighting still to be done. Witnessing Bazan’s onrushing galleys Uluc Ali Pasha decided discretion the better part of valour and disengaged heading for the open sea where he made good his escape.

After four hours of intense and brutal fighting the Battle of Lepanto was over - the Cross triumphant in victory, the Crescent humbled in defeat.

The Ottoman Fleet had been almost annihilated with 210 of 278 ships sunk, captured, or abandoned with many more badly damaged. Ships can be built of course, and they were. Within a year of the defeat at Lepanto the Ottoman Fleet was similar in size to the one destroyed but the 30,000 experienced sailors and soldiers killed were not so easily replaced and they would shy away from any direct confrontation at sea for many years to come.

The Holy League had lost just 17 ships sunk and 7,500 men killed.

It was said that as Don John addressed his men from the prow of the Real and gave thanks to the Blessed Virgin Mary hundreds of miles away in Rome the Pope rose from his chair went to a window and gazing east declared – the Christian Fleet is victorious! He then wept tears of joy and then just as Don John had, he attributed the victory to the direct intercession of the Virgin Mary.

Don John, Colonna, Venier and the others returned to Rome as heroes their triumph at Lepanto celebrated throughout Catholic Europe like none before and few since as Turkish prisoners were paraded in chains through the streets of the Eternal City to the peel of church bells, the incantations of priests, and the prayers of the people.

The reception in Protestant northern Europe was more muted. They understood the threat posed by Islam well enough but at a time of heightened tension which often spilled over into open warfare the presence of an aggressive Islam on the eastern flank of Catholic Europe was viewed favourably as an impediment to Vatican ambition.

The Battle of Lepanto would not prove decisive in the struggle between East and West, between Christianity and Islam but it was significant nonetheless and would be recognised and resonate as such for many centuries to come. Its propaganda value was immense, and it provided further evidence, if any were needed, that Christendom remained in the ascendant and that Roman Catholicism was the - One True Faith; an epic tale of physical courage, moral certainty and spiritual renewal to be retold again and again in music, literature, and art. It is only now since the narrative has shifted and by those heedless of the fact the thread of history endures and remains unbroken that it has been relegated in our consciousness to the back burner of past events.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, War

Share this post: