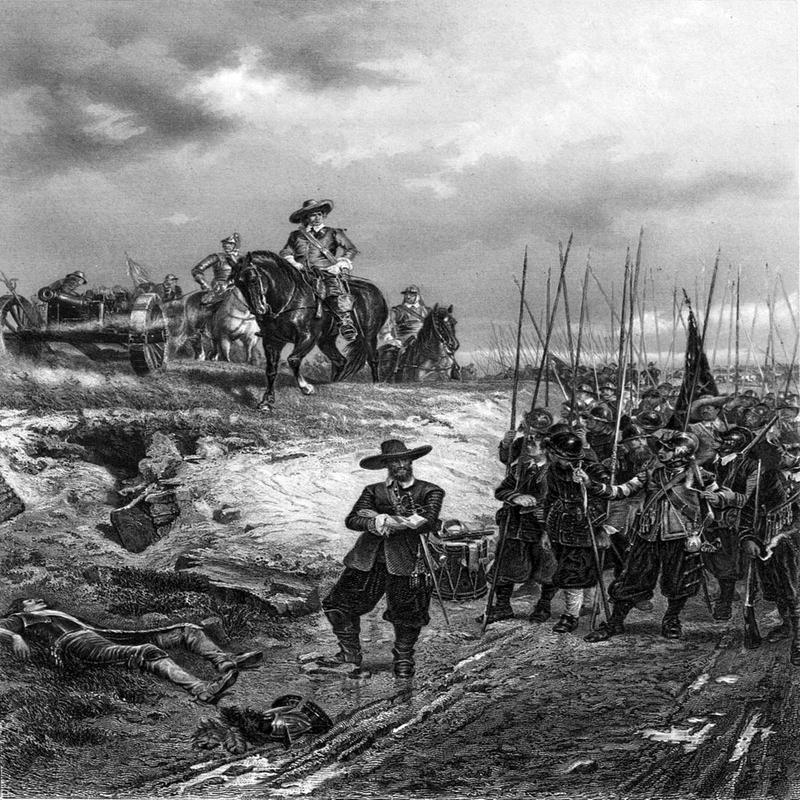

Battle of Naseby

Posted on 3rd May 2021

By the beginning of 1645 the tide of the English Civil War had turned against the king. The years of early success had gone and the signing of the Solemn League and Covenant by a dying John Pym, the guiding hand of Parliamentary resistance to the King, had seen a large Scottish Army come south to support the Parliamentary forces culminating in the defeat of the Royalist Army at the Battle of Marston Moor the previous summer that had seen most of northern England lost to the King. The Royalists were now isolated to regions of support in Wales and the West Country, the King’s capital at Oxford was more vulnerable to attack than ever, and his ability to recruit more troops was severely restricted – A new strategy had to be formed or the war was lost.

There were various options available but on the advice of his General of the Army Prince Rupert of the Rhine, King Charles decided that he should march his army north to link up with that of the Duke of Montrose in Scotland.

James Graham, Marquess of Montrose, was arguably the most successful General of the Civil War. He had raised many of the Highland Clans in the Royalist cause and though his army remained relatively small, rarely numbering more than 3,500, he had defeated superior Scottish Covenanter forces in battle time and time again. It was thought that by linking up with Montrose they could end Covenanter support for the Parliament in England where much of their army was now fighting, and then having secured Scotland march south again recapturing the north of England.

The King’s army was severely reduced by the need to leave 3,000 cavalry under the command of Lord George Goring to maintain the siege of Taunton in the West Country while their plan to wrong foot Parliament by marching rapidly north was stymied by their decision to send the recently trained New Model Army under Sir Thomas Fairfax to besiege the King’s capital at Oxford.

The formation of the New Model Army had been driven by Oliver Cromwell who despaired at the amateurism and lack of conviction he saw around him and believed jeopardised the prospects of victory.

The New Model Army was recruited mostly from veteran soldiers and convinced Presbyterians and within its ranks drinking and swearing was banned, all carried a pocket Bible and prayers were said every day. Officers were promoted according to merit not social rank; discipline was to be maintained at all times and the penalties for disobedience were harsh. The training was also rigorous, intense and exacting. It was to become in effect England’s first professional Army. Some on the Royalist side had suggested that it should be attacked before it was fully formed but the King had seen no strategic value in this while Prince Rupert with a grudging respect was to refer to them as Ironsides.

The defences around the King’s capital at Oxford were formidable and he was confident that it could resist a siege. Nevertheless, his army stormed and ransacked the Parliamentary held city of Leicester in an attempt to draw the New Model Army away from the siege at Oxford.

However, informed that Oxford was not provisioned to withstand a prolonged siege Charles decided to return unaware that the attack upon Leicester had in fact worked and the New Model Army had already broken off its siege.

The King’s decision to return, and the delay it caused to the Royalist plan of action would prove significant and Parliament now warned of the King’s intentions gathered its forces to intercept him.

Prince Rupert aware that Parliaments army was better equipped and would greatly outnumber his own wanted to avoid battle if possible. He also sent orders to Lord George Goring to break off the siege of Taunton and march his 3,000 cavalry north to link up with the King’s Army.

Prince Rupert was an outstanding military commander and the model Cavalier dashing, brave and ruthless. His cavalry was greatly feared and he was a hate figure for Parliament but he was no less hated by many on his own side. He was seen by many Royalists as overbearing and arrogant, too close to the King, and a foreign presence in the English Court. As a result, he was never able to fully draw the Royalist forces together and make them act as a cohesive unit and he often implored the King to take a stronger hand and wield more control over his subordinates. As if to emphasise the point Lord Goring now refused to obey the order to march his troops north.

The Royalist Army’s dash for Scotland was to get no further than the village of Naseby in Northamptonshire where with their path blocked by the New Model Army Prince Rupert immediately advised the King to withdraw back to Oxford while he still could but Charles eager for the fight refused.

Rupert’s advice was to prove wise counsel for as the two armies lined up for battle on the morning of 14 June the King’s Army of 7,400 was outnumbered two-to-one.

It was a foggy morning, the mist lay thick on the ground, visibility was poor and neither side seemed inclined to begin hostilities but the fear of being outflanked by superior numbers forced Prince Rupert’s hand. The Royalist infantry in the centre began a slow but steady advance while Rupert held back his cavalry looking to unleash them at the point of impact to maximise the effectiveness of the attack.

There was only time to unleash one volley of musket fire before the two armies were upon one another and the fighting was fierce and hand-to-hand. Indeed, the Royalist attack was so ferocious that the vastly superior Parliamentary infantry was at first pushed back. The King’s Secretary Sir Edward Walker described the scene:

“The foot on either side hardly saw each other until they were within carbine shot, and made only one volley, our falling in with sword and butt-end of musket did notable execution, so much as I saw their colours fall and their foot in great disorder.”

The Commander of Parliament’s centre Sir Philip Skippon was severely wounded but refused to be carried from the field fearing that his departure would induce panic. Prince Rupert knowing that any advantage had to be quickly exploited now committed his cavalry. They charged with their usual dash and verve. His opponent on the left flank of the Parliamentary formation, Sir Henry Ireton, had already committed many of his men to support the hard-pressed Parliamentary infantry but they had been repulsed by push of pike and Ireton wounded and captured in the process. Without Ireton to lead them his cavalry fell into disarray and were speedily put to flight.

Prince Rupert had committed all his cavalry to the attack, he had no reserve and now an old problem returned to haunt the Royalists. Prince Rupert’s troop of cavalry, formidable and feared though they were made up mostly of gentlemen who pursued the enemy as they would a fox. Despite his best efforts he could neither halt the chase nor rally his men until they reached the Parliamentary baggage train and were some 15 miles from the battlefield.

Oliver Cromwell, commanding the cavalry on the right flank of the Parliamentary Army had no such problems with discipline. He also faced only around 300 Royalist cavalry under the command of Sir Marmaduke Langdale.

Langdale could see from his position that the Parliamentary centre had rallied and that their superior numbers were beginning to tell. He wanted to use his men to support the Royalist infantry but if he did this the army could be outflanked. After some hesitation he decided to attack Cromwell’s cavalry head-on in the hope of chasing them from the field. It was a forlorn hope. Outnumbered more than three-to-one it was a desperate manoeuvre, and he was up against the disciplined cavalry of the New Model Army who would not run. He was also charging uphill which diminished the impact of the charge. After a brief but bloody encounter they were routed.

With Langdale’s cavalry fleeing the field, Cromwell now turned his Ironsides to out-flank the Royalist infantry and attack them from the rear. Seeing they were in danger of being surrounded many of the Royalists troops now panicked and tried to run, others surrendered, but there were also those who fought on.

Prince Rupert’s regiment of Bluecoats for example, refused to yield. A Parliamentary soldier later described how, “The Blue Regiment of the King’s stood to it very stoutly, and stirred not, like a wall of brasse.” They were killed almost to a man.

The King with the battle being lost and with it possibly his throne rode forward with the intention of leading his own Lifeguards into the fray. As he did so a Scottish nobleman the Earl of Carnwath grabbed the bridle of his horse and told him in no uncertain terms, cursing and swearing as he did so, “Would you go upon your death!” It was made plain to him that without the King there was no cause left to fight for.

By the time Prince Rupert and his cavalry arrived back at Naseby the battle was as good as over. He tried to rally his men for one final attack, but it was not to be and he was forced to abandon the field.

In victory some of the Parliamentarians, at least those who were not part of the New Model Army went in pursuit of plunder and stumbled across stumbled upon more than a hundred female camp followers. Intent to both rob and rape the women some armed with knives fought back screaming at and cursing the men in a language they did not understand. Believing the women were Irish Catholic harlots trying to bewitch them they hacked them to death - they were in fact Welsh.

The Battle of Naseby had shattered the King’s main field army. Some 1,500 men had been killed, many more left mortally wounded and 3,500 taken prisoner. Parliamentary losses were 450 killed and a similar number of wounded. The cream of the King’s Army and most of his veteran soldiers had been lost. He would never raise such a force again.

Almost as damaging was the capture of the King’s personal baggage. Among the fine silks and cut glass were letters that showed he was in secret negotiations with the Irish Confederation to bring over an army of catholic Irish mercenaries to fight in his cause. Any doubts that might have remained with regards to fighting the war with the King to a conclusion now came to an end.

Less than a month after the disaster at Naseby on 10 July Sir Thomas Fairfax with his army reinforced to more than 20,000 men cornered Lord George Goring’s force and destroyed it at the Battle of Langport. The West Country was now overrun as Royalist garrison after Royalist garrison was forced to surrender. On 10 September, the port of Bristol, the Royalist’s main access to supplies was lost. King Charles had earlier appointed Prince Rupert its Governor with express orders to ensure it remained securely in Royalist hands. The King never forgave Prince Rupert for surrendering it and he was removed from his command of the army, a little later he returned to Germany.

The King fought on however, he continued to conspire, to try and divide his enemies and raise new forces but besieged in Oxford and with Royalist outposts surrendering every day it was a hopeless task.

In May 1646, he fled Oxford in disguise accompanied by just two retainers. He had hoped to make it to a port and take ship for the Continent but Parliament aware that he might try to escape had them closely guarded and it proved impossible. Wishing to remain out of Parliaments hands he surrendered himself to the Scottish Army based at Southwell. He still hoped he could separate them from their English allies but instead they sold him o his enemies in Parliament with Charles remarking that he had been bartered away rather cheaply. He would eventually be tried, found guilty of treason, and executed on 30 January 1649.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart, War

Share this post: