Battle of the Ebro (1938)

Posted on 27th March 2022

The bitter conflict that consumed Spain in the late 1930’s had been caused by the Popular Front Government’s failure to early quash a right-wing military coup that had been a long time in the making. Their failure to act decisively against the provocations of July 1936 had seen the Nationalists as they were soon to become known establish themselves throughout much of Spain even in cities and geographical areas where they had little popular support.

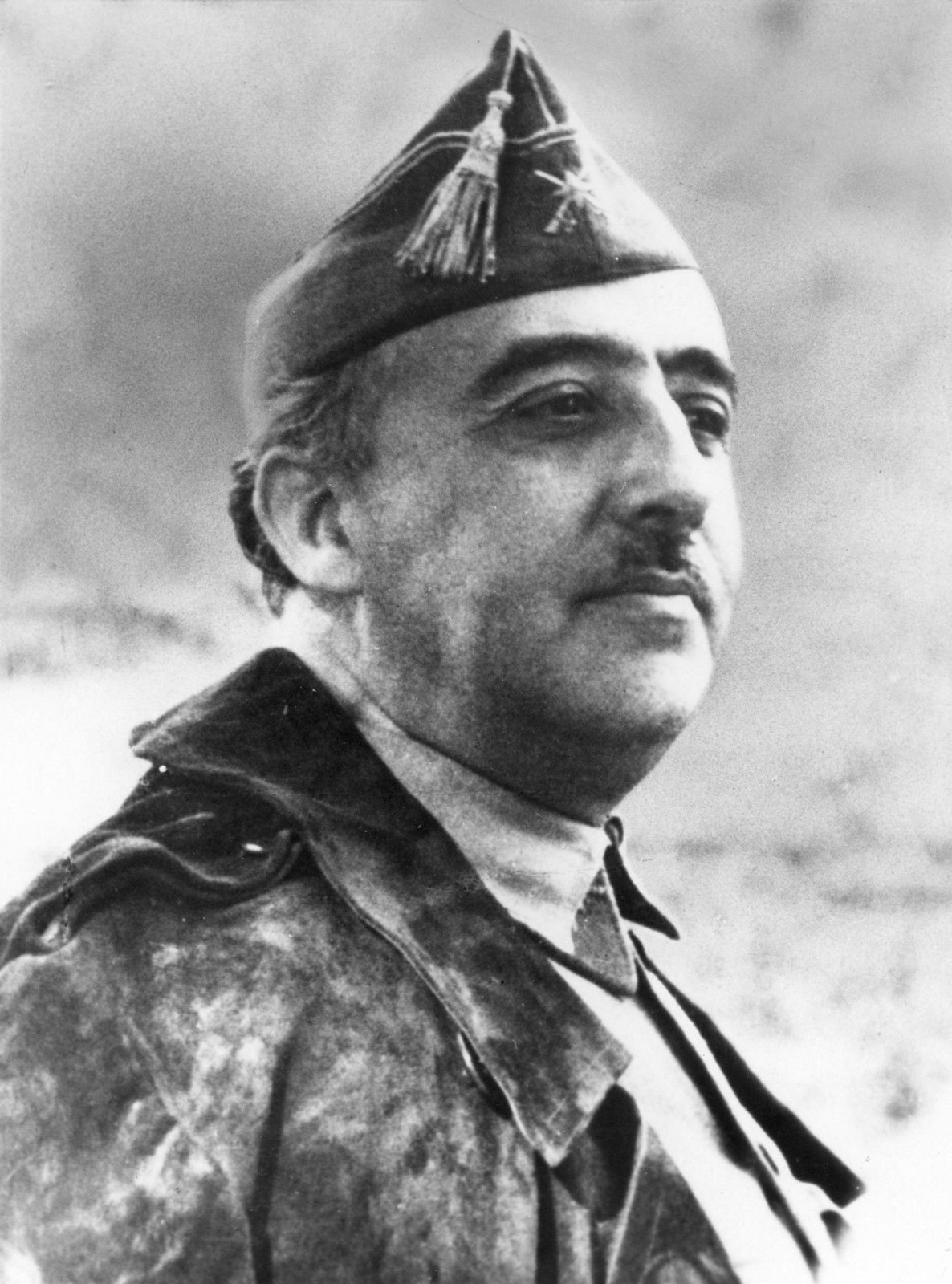

But then, under the leadership of General Francisco Franco they were on a mission to eliminate the twin evils of liberalism and Bolshevism from Spain once and for all and return it to its traditional Catholic and agrarian roots. They referred to their cause as a ‘Crusade,’ and they meant it.

The Republican Government by contrast stumbled from one crisis to another plagued as it was by revolution, counter-revolution and frequent changes of administration. Furthermore, unlike the Nationalists who were provided with arms and combatants by both Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy they were hampered by their inability to purchase war materiel on the open market by the interventions of the so-called Non-Intervention Committee of the great powers. Consequently, they were forced to rely more and more upon Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union merely to survive. That support came at a price however, every shell and every tank had to be paid for with Spanish gold and as if that wasn’t enough Soviet policy soon became Republican policy and barely any appointment of significance was made without the approval of the Kremlin.

The Popular Front Government had legitimacy then but little else, it was isolated and impoverished while the war itself had gone badly from the outset. Other than the successful defence of Madrid and the routing of an Italian Army at Guadalajara the story was, one of defeat after defeat at Jarama, Belchite, Brunete Teruel and many other places; with the Nationalists advancing on all fronts something had to be done - they needed a victory.

The Ebro campaign would begin just five months after the conclusion of the brutal winter battle for Teruel that had seen the Republic squander many of its resources and the cream of its army for no gain. Morale was at an all-time low. Even the much-trumpeted International Brigade had been reduced to a shadow of its former self. Therefore, the army had to be rebuilt and rearmed but little respite was provided in which to do so as just a few weeks after Teruel the Nationalists launched an offensive in Aragon where meeting only sporadic resistance by April 1938, they had reached the sea at Vinaros capturing 40 miles of the Mediterranean coastline and thereby splitting the Republican zone in two.

IIt was thought by many that flush with success Franco would now seize the opportunity to invade Catalonia and take Barcelona but fearing French intervention should his forces reach the Pyrenees he instead directed them towards Valencia. Unlike the Aragon Offensive however, the Nationalist advance on Valencia confronted by well-constructed defences and stubborn Republican resistance would be a hard slog. Losing 4 casualties to every 1 of the enemy the advance soon slowed to a crawl. Perhaps it would have been wise on the part of the Republic given the recent disaster at Teruel to have adopted a similar defensive strategy for the rest of the front. But this wasn’t the plan.

Encouraged by the French Government’s decision of March 17, to reopen its frontier with Spain and the subsequent delivery of more than 18,000 tons of war materiel the Republics Premier Juan Negrin decided to act even if it was in defiance of the dilemma, they now found themselves in. He believed it important to show the world looking on that the Republic remained a viable alternative to a Nationalist takeover of Spain and so he agreed to a plan devised by its chief strategist General Vicente Rojo to launch a major offensive across the wide and fast-flowing River Ebro that would force the Nationalists to abandon their advance towards Valencia and eliminate the corridor that now divided the Republican zone into two. It was a bold strategy and one that appeared to fly in the face of his favoured slogan that merely ‘to resist was to win.’

Negrin had been appointed Prime Minister in May 1937, at a particularly turbulent time for the Republic following the fighting between anarchists and communists on the streets of Barcelona. A medical doctor by profession and former Finance Minister he was considered a safe pair of hands following the resignation of Largo Caballero, the so-called ‘Spanish Lenin’ who had failed to live up to expectations. Some believed he would unlike his predecessor stand up to and reduce communist influence. He would prove quite the opposite.

The army assembled for the Ebro offensive was formidable on paper at least. It numbered 80,000 troops and included many of the best men the Republic had available among them engineers, commandos, veterans of previous campaigns, and elements of the International Brigades but they were not well supported. They had only 150 artillery pieces for the entire length of the front some of which were not only old but obsolete, only 25 tanks were available for the beginning of the assault, while the shells provided for the anti-aircraft guns were in fact defective though this was kept from the troops. As for air cover it would not only prove ineffective but often non-existent as if from an absence of mind.

Overall command would fall to Lieutenant-Colonel Juan Modesto, a sarcastic, humourless and unforgiving man, who had risen through the ranks of the militias. He was deeply unpopular but nonetheless a talented soldier, even if those talents were sometimes exaggerated for propaganda purposes. He was like his hated rival the Commander of V Corps Enrique Lister a communist. Indeed, the offensive on the Ebro was very much a communist affair. All 3 Corps Commanders were communists as also were the 9 Divisional Commanders and 25 of the 27 Brigade Commanders. Any failure on the Ebro would not just be the responsibility of the Republican Government but of the Spanish Communist Party.

The main assault would be at a bend on the River Ebro between the towns of Fayon in the north and Xerta to the south. The centre/left of the front would be the responsibility of Lister and his V Corps while the centre/right would be commanded by Manuel Taguena leading the XV Corps. Opposing them were the Nationalist 50th Division commanded by Luis Campos and the 40,000 troops of General Yague’s much feared and despised Moroccan Division. A not dissimilar number of men then, to the Republican forces about to attack them but unlike them they were not prepared despite intelligence reports indicating a build up of forces on the east bank of the river. No one at Franco’s headquarters it seemed believed the Republic capable of launching a major assault in the wake of Teruel and so soon after the Aragon Offensive.

A little after midnight on 25 July, Republican troops began crossing the Ebro in virtual silence nine men to a boat and unseen under a moonless sky. The Nationalists on the other bank were for the most part taken completely by surprise; and as sentries had their throats slit and soldiers were woken from their slumbers by firing from all directions they began to panic and flee.

While troops assaulted the opposite bank engineers busied themselves slinging prefabricated pontoon bridges across the river and building more permanent structures that would enable the tanks, armoured trucks and artillery to cross.

In the meantime, the fighting was going better than had been anticipated. In the north Taguenas XV Corps found the going tough but still advanced 4 miles but it was in the centre where real progress was being made. Indeed, it appeared for a time as if Nationalist resistance was crumbling as front-line trenches were abandoned and 4,000 prisoners taken. Lister’s V Corps were in fact able to advance 25 miles in a single day virtually unopposed and seize 800 square kilometres of Nationalist territory. Only in the far south at Amposta was there a setback but it was a serious one. The 14th International Brigade mostly French and Belgian were badly mauled and after eighteen hours of intense fighting were forced to withdraw back cross the river leaving behind 600 dead and many more wounded and captured. Nonetheless, the progress made on the first day alone was beyond the Republic’s wildest dreams so much so that even a man as pessimistic as the President Manuel Azana believed that this was at last the turning point of the war. Such optimism wouldn’t last.

While Lister hurried to capture the high ground before advancing on to the small town of Gandesa, an early Republican target, Yague for the Nationalists had been quick to react, bringing forward Baronne’s Reserve Division to help stabilise the line.

Franco, as he always did whenever the integrity of Nationalist territory was threatened, regardless of its strategic value, acted with haste. He immediately withdrew 8 Divisions from other fronts to reinforce those on the Ebro and ordered that dams in the Pyrenees be opened causing the flood water created to sweep away the Republic’s pontoon bridges. They were hastily rebuilt but it caused valuable time to be lost and with no transport available troops were forced to march under a burning sun while their supplies and armoured support lagged far behind. He also ordered the German Condor Legion and planes of the Italian Aviazione Legionaria to bomb the pontoon bridges over the Ebro which they did relentlessly day and night with the Republican Air Force nowhere to be seen.

The early optimism expressed by Republican politicians and their Army High Command began to dissipate as supply problems and Nationalist reinforcements slowed the advance. On 27 July, Lister’s V Corps had tried had assaulted Gandesa behind a screen of T.26 tanks but were forced back with heavy losses. Likewise, little progress had been made in the north while problems of supply were manifest with water scarce, rations reduced and ammunition in short supply. The troops were also exhausted. It was becoming increasingly clear that just a week after it had begun the Ebro Offensive, like all those which had preceded it had stalled.

On 30 July, Modesto took personal command and ordered the attack on Gandesa to resume. Under cover of an intense artillery bombardment the troops advanced and managed to penetrate the outskirts of the town but they could get no further. On 1 August, Modesto ordered the Army of the Ebro to go over to the defensive but this did not precipitate a withdrawal, as a future order of the day would make clear: “Not a single position must be lost, if the enemy takes one there must be an immediate counter-attack and as much fighting as is necessary to ensure it remains in Republican hands – not a metre of ground to the enemy!”

Fine words perhaps, but a little over a week after it had begun the Republican offensive on the Ebro was over. Ill-equipped, under pressure and with little prospect of victory common sense and sound military judgement should have dictated the Republican Army withdraw back across the River Ebro while it could still do so; but by now propaganda issues outweighed any military concerns or strategic priorities. Prime Minister Negrin simply could not countenance yet another Republican setback, and certainly not one of such magnitude, so the Army of the Ebro would remain where it was and endure a constant artillery and aerial bombardment to which they had no answer.

General Franco was no less obdurate in his determination not to leave any territory in Republican hands. His preferred tactic was to bombard the enemy positions from both ground and air until it was little more than a wasteland followed by a targeted but limited counter-offensive. It was relentless lacked mobility and was hardly touched by genius, but it was effective. There would be six such counter-offensives between late August and October all of which captured a little more ground.

It was grim and grinding warfare fought under a burning sun and in temperatures as high as 37 degrees celsius in the shade and on ground so dry it was impossible to dig trenches or dugouts. Those under bombardment merely hid behind rocks and hoped for the best.

On 13 August, the Republican Air Force turned up in strength over the Terra Alta for the first (and last) time. What followed was the largest air battle of the entire war and it was a one-sided affair, the Republics Chato’s and Supermosca’s proving no match for the German Messerschmitt - the Condor Legion would continue to bomb the pontoon bridges with impunity.

With it becoming increasingly evident that the Republics great gamble on the Ebro had failed Negrin renewed his attempts to secure a negotiated settlement to the conflict but doing so from a position of weakness his attempt to open peace talks with Franco were firmly rejected. On 21 September, in an address to the League of Nations he announced the unilateral withdrawal of the International Brigades from Spain. It was a gesture intended to provoke a similar response from the Nationalists or at least cause one or more of the great powers, namely Britain of France, to apply pressure on them to do so.

On 28 October, seven weeks after they had been withdrawn from the line the International Brigades assembled in Barcelona for their farewell parade. President Azana was present to watch the march past, as was Negrin and General Rojo along with the more than 300,000 Catalans who lined the streets. Before they set of the communist orator Dolores Ibarruri also known as La Pasionaria, addressed them: “Comrades of the International Brigade, political reasons, reasons of state, the welfare of that same cause for which you offered your blood with boundless generosity are sending you back, some of you to your own country and others to forced exile. You can go proudly, you are history, you are legend; you are the heroic example of democracy, solidarity and universality. We shall not forget you, and when the olive tree of peace puts forth its leaves once again mingled with the laurels of the Spanish Republics victory – come back!”

It had been an emotional and tearful day no doubt, but it wasn’t as significant as it seemed. By now more than a third of the Brigades were made up of Spanish conscripts while those who had volunteered to fight from the totalitarian states and could not return home were granted Spanish citizenship and assigned to other units. It had for the most part then, been a cosmetic exercise. Neither did it elicit the response Negrin had hoped for either from Franco or those powers on the Non-Intervention Committee. It was not seen viewed as a goodwill gesture, a preliminary to peace talks, but as a sign of weakness; some Italian troops on the Nationalist side were repatriated home as a result but the best remained, and the surfeit was made up with war materiel which was what Franco had wanted all along. Also, the Condor Legion was going nowhere and so long as they remained the Republics days were numbered.

The disbandment of the International Brigades signified something far deeper however, the end of a revolution that had seen idealistic young men from across the world join its ranks to oppose fascism and put their lives on the line to fight for a cause they saw as just - the war was no longer one of ideas but one of survival.

In the early hours of 16 November, obscured by the darkness and a heavy mist the troops of Manuel Taguena’s XV Corps abandoned their positions and withdrew back across the River Ebro - the Battle of the Ebro was over. It had lasted 113 days and had cost both sides dear, but the Republic more so. They had fought themselves to a standstill having lost around 30,000 men killed and 50,000 wounded, captured, missing, many of them the best troops they had available. The guns and tanks lost could not be replaced while their Air Force had been eviscerated and would never recover. Once the element of surprise had passed and time had been lost clearing the areas they occupied of all enemy forces before continuing the advance the Nationalists had reinforced their positions any chance of success had disappeared. The offensive should have been halted there and then but too much hope had been invested in eventual victory for that to happen. When the reality finally dawned on those who had so eagerly trumpeted its early success disillusionment set in and morale slumped.

Nationalist losses had also been heavy (Franco’s obdurate refusal to manoeuvre and instead fight it out had seen to that) though they had only about half the number of men killed while unlike the Republicans any lost equipment could and would be replaced.

A little over two months after the last shot had been fired on the Ebro the Nationalist began their Catalan Offensive. The Republican Army of the North was ill-prepared to fight major campaign but for a time at least put up a stout if sporadic resistance; but it was only a matter of time until the breakthrough came and what followed when it did was collapse as thousands of people military and civilian alike fled towards the Pyrenees and sanctuary across the border in France. On 26 January 1939, Barcelona the cradle of the revolution was surrendered without a shot being fired in its defence.

The one-time Government of all Spain now controlled less than a third of the country. The spiritual and industrial heart had been ripped from the atrophied body of Republican Spain – it had become a Rump State; only a stubborn hatred of the enemy and a lack of alternatives other than flight and exile saw the Republic stumble on for a further three months. Its last great battle would not be against the enemy but between themselves as anarchist and communists fought each other on the streets of Madrid for the right to hoist the white flag (Negrin had lost since fled to France).

On 28 March, the Nationalists entered Madrid unopposed. Four days later on 1 April 1939, Franco declared the war over.

Share this post: