Battle of Towton

Posted on 3rd February 2021

The Battle of Towton which took place on Palm Sunday, 29 March, 1461, was the largest battle ever fought on English soil and it was to prove a pivotal moment in the dynastic struggle known as the War of the Roses between the House of Lancaster and the House of York.

The dispute that was to provoke a war was largely down to the inability of the young Lancastrian King Henry VI to govern his realm effectively. He had ascended the throne on 31 August 1422, when he was only 9 months old and was crowned still a child just seven years later. It seemed to many that he remained a child before in August 1453 having what appears to have been a complete mental breakdown it being said:

"His head hung loose, his tongue lolled in his mouth, and for long periods he seemed unaware of anything that was going on around him."

Henry's rival for the throne was Richard Duke of York the most powerful nobleman in England, a capable and brave but also arrogant and overbearing man. He was in almost every respect the opposite of the amiable always smiling and accommodating Henry.

Richard didn't doubt for a moment that he should be King not his idiot cousin and he certainly had a legitimate claim to the throne as a direct descendant of Edward III, but his ambitions had been so transparent that he had alienated many of his fellow noblemen and his arrogance such that he had been banned from Court thereby denying him political influence. The King’s Counsellors had prompted him to do this because he was clearly putty in Richard's hands, and it was only with great reluctance that the Council had appointed him Regent during the King’s incapacity. He did not fully regain his senses until Christmas Day 1454, when he awoke it was said as if from a dream unaware of what had gone before.

This was not the case with Henry's wife, the formidable Margaret of Anjou who not only loathed Richard but was determined to thwart him in his ambitions and secure the throne for her son Edward, Prince of Wales. Likewise, Richard was willing to take up arms to restore his power and prestige and to pursue his own claim.

The first clash of arms occurred at St Albans on 22 May 1455, when Richard and his ally Richard Neville Earl of Warwick easily defeated a small Lancastrian Army and took the person of the King prisoner. In captivity Henry was effectively stripped of his power and forced to appoint Richard, Constable of England. A few brief years of peace followed but Margaret of Anjou was never willing to accept Richard's pre-eminent role in the country and when fighting resumed in 1459, Richard was forced to flee to the Continent.

While Richard was in exile licking his wounds and tending to his bruised ego his ally the Earl of Warwick had landed with an army from Calais and on 10 July 1460 faced the Lancastrian Army at the Battle of Northampton. The two competing armies were large but the casualties light as the Lancastrian troops simply melted away under a hail of arrows. Henry, no warrior that was for sure was once again taken prisoner and hearing the news of Warwick’s victory Richard returned to England in triumph.

He was dissuaded from deposing Henry by his Counsellors who advised him that it would be better to succeed to the throne legitimately. So instead, he was made Lord Protector in effect most powerful man in the country. Parliament also passed the Act of Accord which dispossessed Henry's son, the seven-year-old Edward, and declared that Richard would succeed to the throne upon Henry's death. This was not necessarily the best arrangement for Richard since he was eleven years Henry's senior but to all intents-and-purposes the House of York had prevailed.

Margaret of Anjou remained at liberty however and with much of her army still intact she retreated north to re-gather her strength and recruit more troops. This was easier than might otherwise have been expected due to the deep unpopularity of Richard, and with the not inconsiderable help of the Welsh Nobleman Jasper Tudor together they raised a considerable force.

Richard now rushed north with just a handful of knights to combat the threat looking to recruit an army as he went.

On 30 December 1460, the two armies clashed just outside the town of Wakefield in Yorkshire where Richard heavily outnumbered with only 9,000 troops to Margaret's 20,000 was unable to prevent his forces from being outflanked and surrounded. Caught in a murderous crush from which they could not escape the Yorkist Army was routed while Richard unhorsed and fighting on foot was killed alongside his second son Edmund, Earl of Rutland. Recovered from the battlefield Richard's body was decapitated and his head wearing a paper crown displayed on a spike over the gates of York, the city that bore his name. With Richard of York dead Margaret of Anjou now marched south determined to take London.

On 17 February 1461, she was intercepted at St Albans by the Earl of Warwick, but the Second Battle of St Albans was to be a Lancastrian victory and Warwick was forced to flee. Henry VI, who still a captive had been made to accompany Warwick was later found perched under a tree singing merrily to himself totally oblivious to what was going on.

With the feeble and helpless Henry back in her charge, Margaret now took the opportunity to blood her son Edward into the world of Kingship by forcing him to order and then attend the execution of several captured knights.

The road to London now lay open for Margaret but her army many of whom were Scots recruited on the promise of plunder were now beginning to desert and return home with their booty but with their reputation for pillage going before them the people of London now locked the gates of the city barring her entry. In the meantime, the deceased Richard's eldest son, the 18 year old Edward Earl of March, defeated a Lancastrian Army at the Battle of Mortimer's Cross on the Welsh border. Following this victory, the Earl of Warwick had Edward declared King of England.

With the House of York usurping the throne if in name only and Margaret of Anjou unable to take London the decisive clash would take place in the north.

Unlike his father who had been a short, slight and embittered man his face twisted as if having eaten a sour apple, Edward was large, bluff, affable and popular with those who knew him. Also, not tainted with the sins of his father many noblemen now flocked to his banner.

Having learned from his father’s mistakes Edward now set about raising an army large enough to meet the threat of any sent against it. The appalling behaviour of the Lancastrians on their march south had provided him with a rich source of recruitment and by February 1461 he had gathered some 28,000 men.

In late March 1461, the vanguard of the Yorkist Army clashed with a small Lancastrian force at Ferrybridge. They had been hoping to secure a crossing over the River Aire but surprised by the Lancastrians had been routed and their Commander Lord Fitzwalter killed before he even had time to don his armour.

Edward responded to this setback by sending a much larger force under the Earl Rivers to take the bridge. In what was a day of savage fighting that left 3,000 dead including the Lancastrian Commander Lord Clifford killed with an arrow to the throat, the Yorkists finally secured the crossing. The way was now clear for the two armies to clash and they did so on 29 March 1461, near the village of Towton.

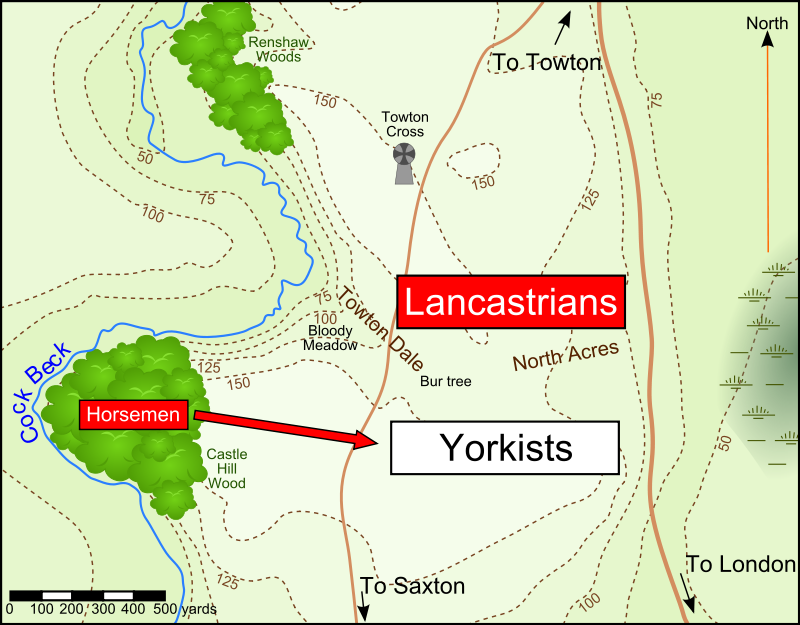

The Yorkist Army had by this time grown to 35,000 men but it was still outnumbered by a Lancastrian Army estimated at some 42,000 men. The Lancastrians appeared to have the advantage numerically but also geographically for they held the high ground and were defended on their right flank by a stream known as the Cock Beck. It’s Commander Henry Beaufort the Lord Somerset, an experienced soldier who had the confidence of Margaret of Anjou had blocked the road to York, the only town of any size capable of replenishing a large army and in a good defensive position was determined to remain where he was - it would be up to his opponents to dislodge him if they could. But it would be the weather as much as the respective commanders which would determine the course of this battle.

And the weather was foul. It was a bitterly cold day, the heavy snow that had already settled on the ground was still falling and the Cock Beck had flooded. The strong wind that was gusting across the open, sodden, ground was also blowing directly into the faces of the Lancastrian soldiers chilling them to the bone and impairing their vision.

The battle began with the usual exchange of archery but with the wind against them the Lancastrian arrows fell woefully short. The Yorkists had no such problems. Indeed, their arrows flew over their intended targets who, should have been prepared to meet them landing instead among troops not yet ready to engage who in their panic pressed down upon the forward line. Seeing this Lord Fauconberg, who despite Edward leading his own army he was heavily reliant upon for battlefield advice saw an opportunity and ordered his archers to unleash volley after volley of arrows without respite into an increasingly dispirited army that could not see them coming. When they ran out of their own arrows, they plucked those of their enemy from the snow where they had fallen short and used them.

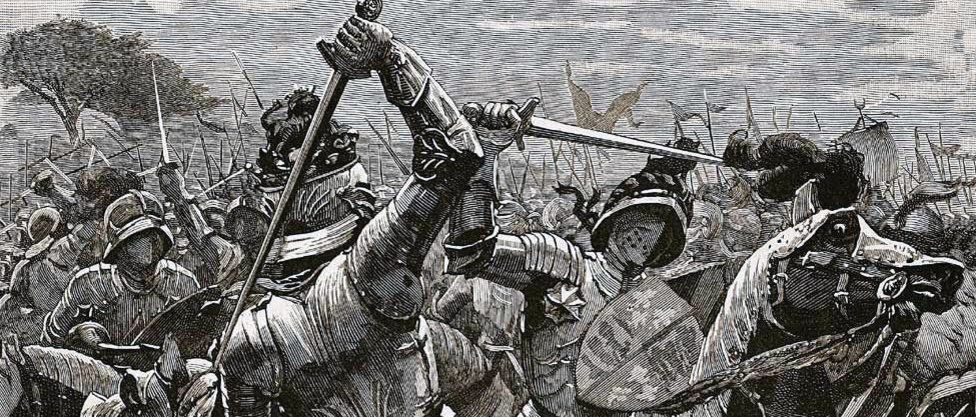

Frustrated and scared the Lancastrians began to break formation and charge towards the Yorkist lines in a desperate attempt to get to grips with the enemy. Unable to prevent it and realising how vulnerable it would make them were it done piecemeal the Lord Somerset ordered a general advance. It was not the mistake he feared it would be but then he had made provision for unexpected events by concealing a force of knights and spearmen in Castle Hill Woods on the Yorkist left who now emerged from their hiding place to lend weight to an attack which had already forced the Yorkist Army to give ground. Indeed, over the next few hours it would struggle to maintain its discipline and come close to crumbling altogether.

The fighting was prolonged, brutal and intense with the visibility so poor that men stumbled over corpses and fought with men that were already dead and as night began to fall conditions only worsened. The Lancastrians could sense victory even if they could not see the fruits of their success. The Yorkist situation meanwhile was becoming increasingly desperate, and the tall, physically impressive Edward could be clearly seen in the thick of the fighting trying to rally his men. His example was an inspiration but nonetheless all appeared lost.

Late in the day the Duke of Norfolk arrived on the battlefield with 2,000 Yorkist reinforcements fresh men unwearied by their travails and eager for the fight who crashed into the Lancastrians right flank. This sudden and heavy blow that arrived as if from nowhere not only took them by surprise but panicked already exhausted men into flight as they threw down their weapons scrambled over one another in their desperation to get away stripping off their armour as they did so. They fled towards the raging Cock Beck across a field that would soon become known as the Bloody Meadow as in the rout that followed thousands were cut down, crushed, suffocated in the mud or drowned in the swollen rivers.

Those ordinary soldiers taken prisoner were given no quarter and were either clubbed to death or had their throats cut while the 42 Knights who had been taken for ransom were instead beheaded on Edward’s orders.

The casualties incurred at Towton were unlike any other seen on English soil with as many as 16,000 Lancastrians either killed in battle, in flight or executed once the fighting had ceased. The Yorkists had likewise lost heavily with around 12,000 men dead. Among those killed in the battle were 28 Peers of the Realm, or half of all those in the country including the most powerful northern magnate, the Duke of Northumberland.

The Battle of Towton was a great Yorkist victory but it was not to be as decisive as first appeared for though the Lancastrian Army had indeed been routed and destroyed neither Margaret of Anjou nor Henry VI had been present.

They had remained in York and when they heard news of the defeat they fled along with the Lord Somerset and the few knights they had remaining to them to Scotland. As long as they remained alive, Edward’s triumph would not go unchallenged.

Despite Henry, Margaret and many of their leading supporters still being at liberty the victory at Towton had seen Edward succeed where his father had failed, and he was formally crowned King of England in London in June 1461 to great acclaim from his supporters and the people of the city.

Regardless of many minor rebellions Edward was to remain securely on the throne for the next ten years. In 1465, the deposed Henry VI was captured at Clitheroe in Lancashire and taken to London where he was kept in the Tower but considered harmless and with much sympathy for his condition he was not kept closely confined and was well treated. Margaret had earlier escaped to France with her son, the young Prince of Wales.

Despite her exile Margaret had remained busy and was still determined to secure the throne for her son, the rightful heir, and was now plotting with the Earl of Warwick. He had seen his own ambitions thwarted when Edward declined to marry his daughter as promised instead taking as his bride the Lancastrian supporting Elizabeth Woodville. He was furious at what he saw as a betrayal and opened negotiations with Margaret expressing his willingness to change sides.

Aware of Warwick’s determination to secure his own family in the line of succession Margaret sealed the deal by marrying her son Edward to his daughter, Anne. Then in alliance with King's ever treacherous brother the Duke of Clarence, they invaded England.

Edward taken completely by surprise was forced to flee in haste to the Continent with his other, loyal brother, Richard.

Warwick's success was to be short-lived however and within a few months Edward and Richard were back with the Duke of Clarence having once again flipped sides. The opposing forces met at Barnet on 14 April 1471, and in a chaotic affair fought in a thick fog Warwick's troops attacked one another by mistake and in the ensuing chaos his army fell apart before the Earl himself was killed while stumbling around in the dark trying to find his horse.

Margaret, who had landed in England a few days earlier, now took command of what remained of the Lancastrian Army but with only 3,000 men she was in no condition to confront Edward and when her army was finally cornered at Tewkesbury on 4 May 1471, it was routed and her beloved son, the 17 year old Edward, the fulcrum of all her ambitions, discovered skulking in a forest was executed on the orders of the Duke of Clarence.

With her son dead the formidable Margaret's spirit was at last broken and having made no effort to flee she was taken into captivity. Despite her constant scheming, her life was spared, and she was sent into exile in France from where she never again involved herself in plots against the regime.

It was evident to Edward that as long as Henry VI remained alive he would be the focus of future plots and so having expressed his regret at having to do so on 14 May 1471, he ordered his murder.

The Duke of Clarence discovered once more to be conspiring with Edward’s enemies was made to pay with his life by his older brother who had him lowered upside down into a vat of Malmsey wine and drowned in an execution overseen by his younger brother, Richard.

With all his rivals now dead or in exile, Edward was at last the undisputed King of England and the War of the Roses was over, for the time being at least.

Share this post: