Benito Mussolini: Duce

Posted on 18th February 2021

Benito Mussolini was the first European Fascist Dictator and the man to whom all those who followed looked for inspiration. He set the tone and style of fascism – the uniform, the salute, the staged rallies and the relentless propaganda. He established the One-Party State and the Corporate Society. He would demand living space for his people, and he would pursue a policy of aggressive expansionism overseas. He would make Italy great again and all this he would do behind the thin veneer of legality.

Adolf Hitler was a great admirer and would remain so all his life but unlike the Fuhrer, Mussolini was a man plagued by self-doubt and who was driven by ambition not ideology; and he would find his doubts justified for though he was to rule Italy for more than twenty years and provide for her a place on the world stage that had not been seen since the glory days of the Roman Empire his creation was never more than a paper tiger.

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was born in the village of Predappio in the Romagna on 29 July 1883. He was the son of a radical blacksmith and was named Benito after the Mexican revolutionary, Benito Juarez.

Helping in his forge the young Benito would imbibe his father Alessandro’s socialist politics and in doing so it appears also inherit his hatred of convention, disrespect for authority and anti-clerical views. At school he was a tearaway some might even say a bully who never shrank from intimidation to get his way and was expelled on several occasions even once being arrested for stabbing another pupil in a playground brawl. Such behaviour appears to have been encouraged by his father but came as a disappointment to his devoutly religious mother Rosa, who tried to instil some discipline into her son by making him attend Mass.

Despite being a troublesome youth who scorned learning and was disinclined to listen to his elders he did eventually pass his exams and qualify as a schoolteacher. It was not a profession he ever had any intention of following, however.

In 1902, he left Italy for Switzerland where he lived rough and found work where he could as a bricklayer working on construction sites. It was during these early years that he was first introduced into the life of the political activist soon acquiring a reputation as a Left-Wing rabble-rouser.

Wherever there was an industrial dispute it seemed there was the young Benito Mussolini encouraging the workers to down tools and go on strike. He was eventually expelled from Switzerland as a political undesirable.

In 1911, he was arrested at a demonstration in Forli against Italian aggression in Libya for which he was to serve five months in prison. This brought him to the attention of leading members of the Italian Socialist Party who were impressed by his energy, his hard work and his undoubted commitment to the cause and he was rewarded in April 1912 with the Editorship of their newspaper, Avanti!

This was around the same time as he was having an affair with a young beautician named Ida Dalser who, unable to find work because of his reputation as a political troublemaker, had been supporting him financially. She had already given birth to his son also named Benito, and sometime in 1914 they married but not long after became estranged. It appears that when he no longer needed Ida’s money, she and the child became a burden at which point he simply walked away to spend more time with Rachele Guidi, his lover since 1910.

Upon coming to power Benito did all he could to destroy the evidence of a marriage ever having occurred but unfortunately for him, Ida went public declaring time and time again that she was the wife of the Fascist Dictator and the mother of his child. Moreover, they had never divorced and that he was a bigamist, for Mussolini had since married Rachele.

Determined to silence her and prevent further scandal he had Ida abducted from her home and interned in the Psychiatric Hospital at Pergine Vulsugana where she died in 1937. Their son Benito was also taken away and locked up in the Asylum at Mombella where he was likely murdered in 1942.

Unperturbed at his own behaviour and untroubled by their fate the Ida Dalser affair perhaps reveals more of Mussolini’s dark soul than any dry analysis of his political career ever could.

He had married Rachele Guidi with whom he was to have five children as early as December 1915, but he was never really interested in family life merely wanting to prove, himself a man and secure his legacy and throughout his life he was to have a string of lovers. He had always been attractive to women despite being physically unimpressive and lacking it was said in personal hygiene but the power of personality it seems was enough to overcome any shortcomings.

Mussolini soon proved himself a talented journalist and an outstanding Editor of Avanti! And under his tutorship it was anti-capitalist, espoused an aggressive international socialism and vigorously opposed Italian intervention in the Great War. When Italy did enter the war on the side of the Allies in 1915 however, it changed everything. In October 1915, he wrote: “It is to you, young men of Italy, that I address my call to arms. Today, I am forced to utter loudly and clearly in sincere good faith that fearful and fascinating word – War!”

In this one short phrase he betrayed everything he had never believed in. He betrayed his father, his colleagues his party and moreover the Italian working class that he had vowed to defend. Called to a meeting of the General Committee of the Socialist Party in Milan he was forced to provide an explanation for an editorial that was in direct contravention of party policy. He refused to do so, refused to retract his words, and would not issue an apology. As a result, he was sacked from his position as Editor of Avanti! and expelled from the Socialist Party. Four weeks later he established his own newspaper, II Popolo d’Italia.

Earlier in August he had been conscripted into the Italian Army where he saw active service on the Isonzo Front and rose to the rank of Corporal. He was invalided out of the army in February 1917, when he was injured by an accidentally exploding mortar shell. Something he was to make much of in later life.

Following the end of the war there was great anger over the so-called “Mutilated Peace” when Italy received very little for the many sacrifices she had made – 564,000 dead, an economy ruined, and a discredited political establishment – it wasn’t long before the country descended into chaos. Mussolini took advantage of the power vacuum created to re-establish the Fasci di Combattimento and the Squadristi, paramilitary groups that had originally been formed by Dino Grandi to intimidate political opponents. He was to combine these to form the Partito Nazionale Fascista (National Fascist Party). In very short time it had attracted 300,000 members drawn mainly from the ruined middle class and disgruntled ex-servicemen.

At the Fascist Party Congress of October 1922, Mussolini made it clear to those in attendance that he intended to take power by force telling them: “Either the Government will be given to us, or we will seize it by marching on Rome.”

He had hoped to intimidate the weak Liberal Government into presenting him with the reins of power but when this did not materialise the call went out for fascists from across Italy to gather outside the capital for his threatened march on Rome.

The Marcia Su Roma of 27 October 1922 was intended to be a show of force, but it was in fact patchily attended and those fascists who did turn up were unimpressive to say the least. Less than 30,000 in number, ill-disciplined and poorly armed they looked less like an invading army and more like people asking for a handout. They could easily have been dispersed and the Italian Premier Luigi Facta was all for doing precisely that. He requested that King Victor Emmanuel permit him to call out the troops and declare a State of Emergency, but he refused. Mussolini, fearing bloodshed, had stayed away from the march itself only arriving in Rome the following day by train. On 29 October he was summoned to an audience with the King. The next day Facta was dismissed, and Mussolini was called upon to form a Government.

The March on Rome had been a shambolic, poorly organised, farcical but successful coup d’etat. Mussolini had not seized the reins of power by force as he had hoped but had been presented with them by a sympathetic King. Even so, the events of 27/8 October 1922, were to become enshrined in fascist mythology and were much admired by Adolf Hitler whose own attempt to do similar in Munich in November 1924 ended in disastrous failure.

From the outset Mussolini declared his scorn for parliamentary politics and the Liberal State declaring it “a mask behind which there is no face, scaffolding where there is no building.”

His new fascist Italy would be different, it would be created in his image, and it would have his face, quite literally.

It is easy to mock Mussolini’s megalomania, condemn his thuggery and despair at his collaboration with Hitler but what did he achieve for Italy? Why does the Fascist Party he formed still prosper in the Italy of today even if in other barely disguised forms? Why do the ideas he espoused still find such a willing audience? Why is the name Mussolini still venerated in so much of the country and why does it still cast a spell upon so many Italians? And why is his hometown now a shrine to his memory?

In October 1922, when he came to power Italy was a desperately poor country. It had only been formed as a unitary State in 1871 and was in many respects still a divided social and political entity. Much of the land remained uncultivable and industrial production had ground to a halt following the factory lockouts of 1919. The country had suffered terrible losses in the Great War, and it was paralysed by inaction and economic chaos. It seemed too many that Italy was on the brink of revolution, a Bolshevik revolution. The Democratic State had shown itself unable to cope with the crisis but the ambitious Mussolini was determined to show that he could and during the early years of his rule he brought stability to Italy after so many years of chaos and the people were relieved. He re-established the Catholic Church and the people were pleased. He pursued an aggressive imperialist foreign policy and the people felt proud to be Italian again. But all this was almost derailed before it began.

In June 1923, he passed the Acerbo Law that guaranteed any Party that received 25% or more of the vote in a General Election two-thirds of the seats in the Italian Parliament. This was designed to ensure that the powerful Fascist Bloc would remain in power for perpetuity and just to make sure that they amassed the number of votes required Mussolini unleashed his Squadristi to threaten and intimidate the electorate. The Fascists won by a landslide, but this wasn’t to be the end of it.

On 30 May 1924, the socialist politician Giacomo Matteotti stood up in the Chamber of Deputies denounced the elections as fraudulent and demanded that the results be invalidated. He was to repeat this demand on two further occasions and intended to do so again, that was until 10 June when his body was found on the outskirts of Rome. He had been stabbed to death.

No one was in any doubt that Mussolini was behind the murder and what resulted was a political crisis so severe that it appeared inevitable that his government would fall. Certainly, he thought so and waited in despair for the phone call from the King dismissing him from office. But the opposition was weak and made the strategic error of walking out of Parliament and providing Mussolini with free reign to embark upon a cover-up. He survived but no one could now be in any doubt as to what fascism meant and what sort of Government Mussolini’s would be. It would be one that would not tolerate free speech, would not tolerate dissent and was willing to commit murder to maintain itself in power.

Having survived the crisis of the Matteotti affair, Mussolini now embarked upon a massive programme of public works. He may not have got the trains to run on time quite in the manner so often suggested but it was a useful metaphor for what he did do, he got Italy back to work. In a series of massive public works he drained the Pontine Marshes, constructed the autostrada and in response to the crippling strikes of 1919 abolished the Trade Unions. In 1926 he introduced the Carta del Lavoro (Charter of Labour) which banned the right to take industrial action and was pivotal in his creation of the Corporate State.

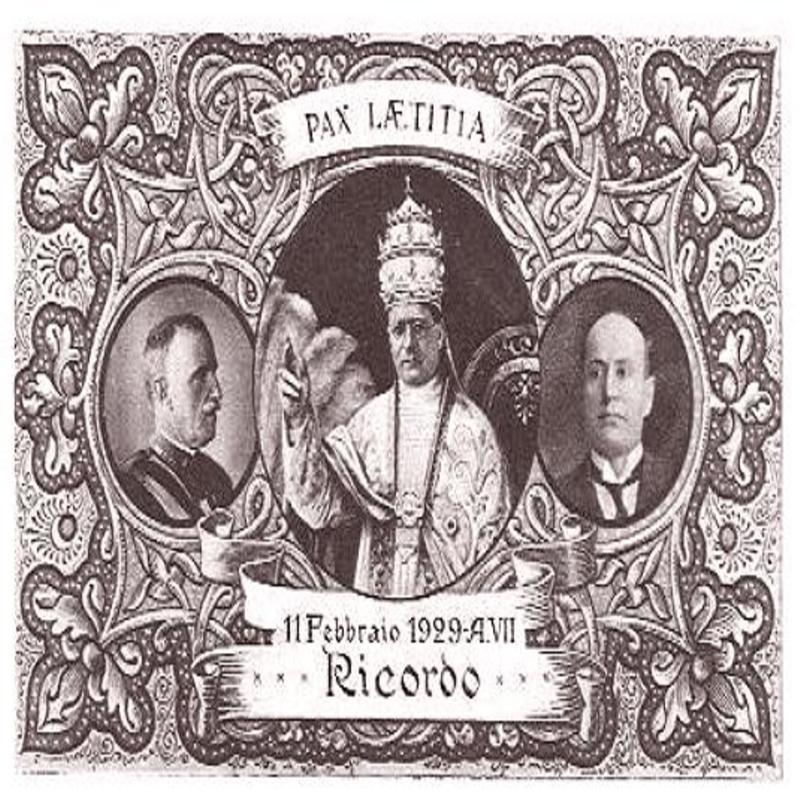

On 11 February 1929, Mussolini signed a concordat with the Catholic Church.

The Lateran Pact as it was to be known provided the Church many of the things it had sought for hundreds of years. Under its terms the Vatican was granted Statehood and was no longer subject to Italian law while Catholicism was recognised as the State religion; Catholic schools and seminaries in Italy would now have special status, birth control and freemasonry were banned, and the clergy were exempt from taxation. In return, Mussolini’s Government received the moral legitimacy it craved.

For the fiercely anti-clerical Mussolini the signing of the Lateran Pact was difficult, but he recognised its advantages and understood its benefits. Catholicism was a unifying factor in a country where politics had only ever sown division. Nevertheless, for a time he continued to speak scathingly both publicly and privately of the Church so much so that at one point he was threatened with excommunication. It took time for him to reconcile himself to the new arrangement but by 1932 a reasonable degree of harmony between State and Church, Duce and Pope had been restored. Following their reconciliation Pope Pius was to praise Mussolini as a man of God, writing that “Italy has been given back to God and God to Italy.”

Over the next ten years Mussolini was to bring order to a lawless land. Even the Mafia were forced underground.

With stability restored he set about making Italy once again a recognised power in Europe and the World and he had a great many admirers among them H.G Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Mahatma Gandhi, Winston Churchill and of course, Adolf Hitler. But Mussolini’s Italy was a straw man. Its economy remained weak, its agriculture was ailing, and industrial production had barely increased since the turn of the century. More significantly perhaps, its much-vaunted military machine was the myth of propaganda.

HHuge economic initiatives were undertaken with II Duce stripped to the waist and with the sun on his back there to promote them digging ditches, bringing in the harvest, even wrestling with lions but for all the fanfare they achieved little. His heavily promoted “Battle for the Land” which was designed to reclaim land, make it cultivable and then redistribute it to the poor and landless thereby reducing unemployment and increasing the grain yield making Italy self-sufficient was a dismal failure and had to be abandoned in 1940. Likewise, his “Gold for the Fatherland” campaign which encouraged people to donate their jewellery to the State did little to offset the worst effects of the Great Depression.

The more Italian businesses failed the more Mussolini nationalised them. This proved a terrible burden on the Treasury and only increased the national debt. But appearances were all important to Mussolini and his fascist regime. Italy could not be seen to be failing and locked factory gates and boarded up shop windows were not to be tolerated.

Italy was also a Police State where no dissent was permitted, and the censorship of the press was total. Mussolini himself appointed Editors depending on their fascist credentials and would spend every morning indicating those articles he did not wish to see published while personally blue-pencilling others.

Elections for Local Authorities were abolished in 1926 with Civic Officials being appointed by the Fascist Grand Council from a pre-determined list that would then be put to a plebiscite. Teachers and Civil Servants were also appointed according to their Fascist Party Membership.

Italian Fascism had not been overtly anti-Semitic at its conception and in the beginning, it had many Jewish supporters. But overtime this would change as Italy came under increasing pressure from their German ally to be more ideological and rigorous in its approach to racial issues and Mussolini himself came to quite like the notion of their being an Italian Master Race, though the truth was that he never quite believed it.

Despite having a relatively small Jewish community, only 48,000 during the inter-war period, Mussolini was eager to prove to Hitler that Italian fascism was serious about racial purity and on 2 September 1938 Italy passed its first anti-Semitic Laws. Despite the intense propaganda campaign that had preceded their implementation the new laws did not go down well with the Italian people who bombarded Mussolini’s office with letters of protest. Nevertheless, Jews were banned from public life and Jewish students were forced to leave University, Jewish Civil Servants were forced to resign, and Jews were even banned from holidaying in Italian resorts.

Mussolini the founder of fascism felt both threatened and intimidated by the rise and power of Nazi Germany and he would do whatever was necessary to maintain his status as an equal partner. Italy would be as racially pure as Germany if that was required, and they would be as harsh as the Nazi’s if a point had to be proved.

By the 1930’s the fascist propaganda machine was working full steam ahead and Mussolini was no longer just the leader of the governing party and Premier of Italy he was - Duce the Statesman, Duce the Man of Action, Duce the Playwright, and even Duce the Musician. There was it seemed nothing that the Duce could not do, even if his detractors declared him unfit to be in polite company.

Posters of Mussolini striking his familiar lantern jawed pose seemed to adorn every wall, statues appeared in most town squares, and his bust was displayed in shop windows. But he remained a work in progress. He lacked polish and was never comfortable in bourgeois circles. He was aware of how absurd he looked in top hat and tails and always felt more at ease in military uniform. He also had to learn to tame his language which was often earthy and coarse and for which he was aware he was mocked.

Yet for all the bravado and grand gestures Mussolini remained an essentially timid man who wished to appear otherwise. His bullied only the weak and his strange affectations, the protruding eyes, and the pouting lips were attempts to appear earnest, to seem fierce. He would keep his distance from people afraid that if they got too close, they would discover weakness, and there was never anyone he could truly call a friend. He still had his lovers of course and these were many. But even with them he would rarely laugh or smile because to do so made him appear vulnerable.

Though he worked hard he rarely stayed up late though the propaganda maintained that he remained vigilant and at his post throughout the night. The truth was he enjoyed his bed and would often be found asleep at his desk.

He was also never short of bombast and spoke often of the glory of war:

“War alone brings up to their highest tension all human energies and imposes the stamp of nobility upon the peoples who have the courage to make it.”

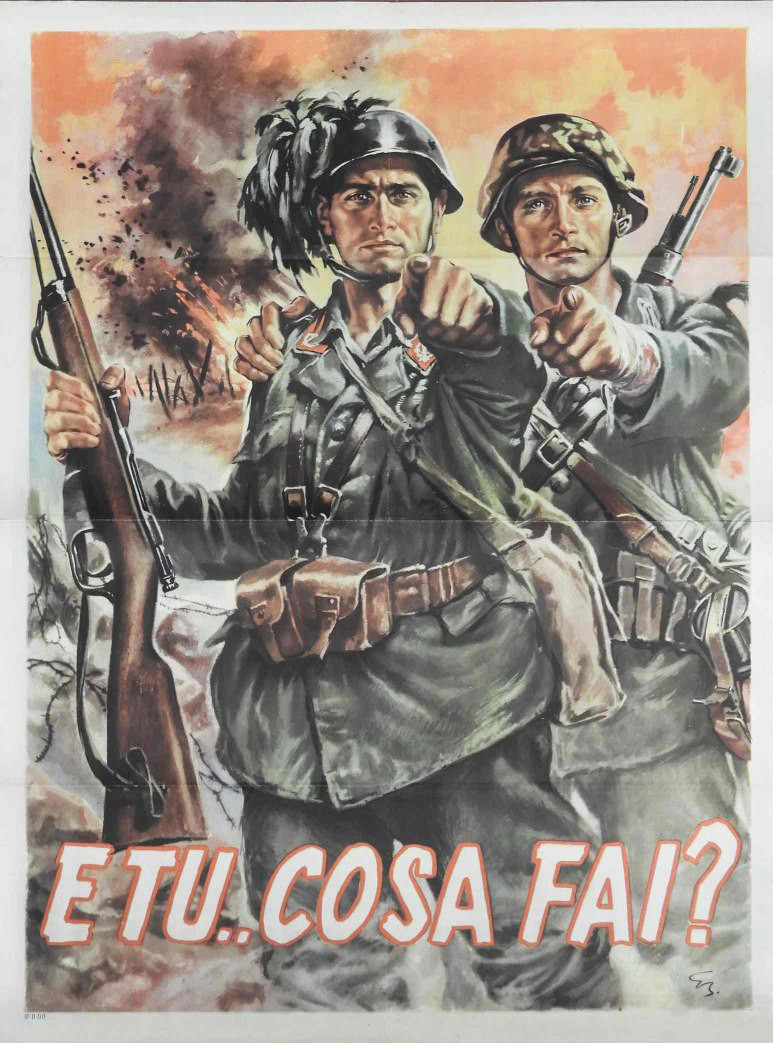

Even so, he must have been aware of Italy’s military weakness. The Army was woefully underfunded, poorly equipped and incompetently led and he’d had the good sense to remain neutral upon the outbreak of war, but he was biding his time just waiting to see which way the tide turned. He was in fact desperate to participate in this history defining moment and with the British having evacuated their forces from Dunkirk and the French Army on its knees and close to capitulation he acted and on 10 June 1940, from the balcony of the Palazzo Venetia in Rome, Mussolini declared war on Britain and France. He would bring his one hundred thousand Italian bayonets to bear, after all.

It was a declaration greeted with wild enthusiasm by the crowds thronging below him but the response in the country generally was more muted. Mussolini thought the war already won and he had earlier said that he just needed a thousand Italian dead to be able to sit at the negotiating table. He was in fact to get 293,000.

The war was a disaster for Italy from the outset as Mussolini, without consulting his German ally ordered his forces to take the offensive. The large Italian Army in the Western Desert ordered to advance on foot and with little air support was heavily defeated by the British and had to be rescued from disaster by Rommel’s hastily formed Afrika Korps.

In October 1940, he ordered his army to invade Greece. Again, little preparation had been made and again it was a disaster as the Greeks counter-attacked, forced the Italians out of the country, captured much of Italian occupied Albania and seemed as if they might advance as far as Italy itself. Once more they had to be rescued by their German ally.

As the war progressed Mussolini became more and more of a peripheral figure as the Great Fascist Dictator’s boasts of Italy’s military prowess, the martial spirit of its people, its strong economy and powerful war industries were proved to be so much hot air. By the spring of 1943, Italy was on the brink of defeat and was only being kept in the war out of fear of its German ally.

The Italian people were also fast becoming disillusioned with their Duce who had told them of their strength and built up their hopes yet there had been no good news since the beginning of the war; Italy’s armies had been defeated in the field, its factories had virtually ceased production, goods were scarce, food was in short supply and the casualties were mounting. On 19 July, Rome was bombed for the first time.

Mussolini feared that the Allies were seeking to invade Italy as a precursor to a full-scale assault on Fortress Europe. The most obvious port of entry was the Island of Sicily. In response he ordered that Sicilian Divisions be stationed on the island with orders to defend their homes to the last man. When in July 1943 the Allies invaded Sicily, more interested in protecting their homes than defending them they surrendered in their droves with hardly a shot being fired in anger .The hollow edifice that was Italian fascism was now being exposed to the world and Mussolini’s declarations of recreating the Roman Empire, of making the Mediterranean Mare Nostrum (Our Sea) and of leading the unified Italian State, one people under one leader to its manifest destiny as the First Among Nations lay broken and scattered about like the ruins of Rome itself.

On 24 July, Mussolini was summoned to attend an especially convened meeting of the Fascist Grand Council which had not gathered since the beginning of the war. There he was condemned for his running of the country and given a severe dressing down. His oldest ally, Dino Grandi, then called for a resolution demanding that the King to resume his full constitutional powers. This was in effect a vote of No Confidence and Mussolini lost it heavily by a margin of 19 votes to 7.

Mussolini, who was not used to being spoken to in such a manner or of being treated with so little respect did not appear to understand what was going on and having said little throughout the meeting was to leave it in a state of shock. The following morning, he turned up for work as usual and for a time it seemed that nothing had changed. Later that afternoon however he received a phone call summoning him to the Royal Palace. He was eager to tell the King of the peculiar events of the previous day. Instead, Victor Emmanuel III sacked him. As he left the Palace no longer ruler of Italy, the Military Police placed him under arrest.

It was a tame almost strangulated end to the career of a man who had dominated Italy and had been at the forefront of the world political stage for more than twenty years and when the announcement of his dismissal was made later that night in a radio broadcast there was barely a ripple of dissent. The Fascist Party he had established, and which had served as an inspiration to so many was abolished two days later.

Now a prisoner, Mussolini was moved from place to place and it seemed that no one quite knew what to do with him until finally he was taken to the Campo Imperatore Hotel at Gran Sasso high in the Apennine Mountains; but he wasn’t to remain under lock and key for long and would soon turn up again like the proverbial bad penny he was proving to be.

On 12 September 1943, he was released following a daring raid by German Fallschirmjager, or paratroopers, led by SS Colonel Otto Skorzeny. The Germans had expected resistance from the Italians guarding him but there was none and so Skorzeny was free to greet Mussolini with the words: “Duce, the Fuhrer has sent me to set you free”, to which he replied “I knew my friend would not forsake me.”

Mussolini, who some described as being in a strange trance-like state was flown to Vienna for an overnight stay and from there onto the Fuhrer’s Wolf’s Lair Headquarters at Rastenberg in East Prussia. Hitler was shocked at the sight of his old ally who was dishevelled, in poor health and had lost a great deal of weight. He was also melancholic and despairing of the future. Hitler tried to cheer him up with stories of how he had survived attempts to assassinate him which he insisted was providential, and proof if any were needed, that they would ultimately triumph. It did little to lighten the once Italian Dictator’s mood.

Hitler was also disappointed that he had no desire to go after the men who had deposed him. Indeed, Mussolini appeared to have lost all fight. The bluster, the bombast, it had all gone. Even so, the Fuhrer insisted that he return to northern Italy and establish a new fascist regime. Mussolini believing somewhat naively that he could now just retire from politics and live quietly was disinclined to get involved but Hitler gave him little choice.

The Italian Social Republic, also known as the Salo Republic, was formed on 23 September 1943 in those parts of northern Italy still under German occupation. Though Mussolini was appointed its nominal leader it was in effect a puppet Government under SS control, but it did have its own Italian Army under the command of the devoted fascist Rodolfo Graziani, the so-called Butcher of Libya. It was used for the most part to maintain order and hunt down Italian Partisans in what had now become effectively an Italian Civil War.

In time Mussolini would regain some of his old fighting spirit and the bombast and bravado would return with him even at one point threatening to turn Milan into the Italian Stalingrad, but he would soon descend into melancholia once again confining his darkest thoughts to his personal diary. Neither was he any longer trusted by Hitler who had SS Guards posted in the grounds of his home where he was kept under constant surveillance.

There was to be no Italian Stalingrad and as the Allies closed in on the Salo Republic, Mussolini made plans for escape. He had wanted to do so for some months but was frightened of being caught and falling into the hands of the SS. Finally, he joined a convoy heading for Switzerland with his lover Clara Petacci and most of his Cabinet. He thought that once in Switzerland he could negotiate his surrender to the Western Allies where he might receive a fair hearing. After all he’d had his admirers in the past and he neither shared Hitler’s apocalyptic vision nor his genocidal racial agenda. Also, unlike his old ally suicide had never crossed his mind.

On 27 April 1945, his convoy was intercepted by Italian Communist Partisans of the 52nd Garibaldi Brigade near Lake Como. Despite being dressed in a Wehrmacht uniform Mussolini was an easily recognisable figure and once his identity had been confirmed by Political Commissar Urbano Lazzaro, he and his lover Clara Petacci and the rest of the Salo Government were taken to the village of Guilino di Mezzagra to await their fate. The order soon came from the Communist High Command - they were to be executed the following day.

Mussolini could not understand why they did not value him as a captive and a hostage but nothing he could say would make any difference. Vain to the end he demanded that they shoot him in the chest. Clara Petacci now began to scream and plead for his life. When her pleas were ignored and at the last moment, she threw herself in front of his body she too was shot. Whether she would have been executed in any case is uncertain. The coup de grace was administered by Colonel Valerio (Walter Audisio) who shot them both in the head.

Following their execution their bodies were taken to Milan and put on display, hung up by their heels from meat hooks at a gasoline station in the Piazzale Loreto where they were spat upon, stoned and beaten with wooden poles.

It was an undignified end for a man to whom self-esteem had meant so much, and it was one the Fuhrer was determined not to share.

Share this post: