Blood River

Posted on 13th April 2022

Some events live long in the memory of a people and become the foundation myth of a nation; they are not easily expunged neither should they be for without them a people can cease to exist.

In 1836, Dutch settlers, known as Boers, weary of living under British rule in Cape Colony began moving east into the South African interior in what became known as the Great Trek. These Voortrekkers were determined to establish a Republic of their own where they could live and worship as they pleased and what began as a trickle soon became a flood. The problem was the land they sought to settle belonged to others. Even so, they had no plan of conquest they would get what they required through negotiation, or so they believed.

One of the leading Voortrekkers, Piet Retief, was already in advance negotiations with the Zulu leader Dingane for land between the Drakenberg Ridge and the coast near Port Natal. It was an area Retief thought was suitable for the Boers of his party and he had a treaty drawn up that Dingane had indicated he was willing to sign provided Retief and his followers recover some cattle for him which had been stolen by a rival tribe. This he did handing over some 700 head of cattle to the Zulu leader in person. It seemed the deal was done, all that remained was for Dingane to sign the treaty and the land would be available for settlement, and Retief was invited to the Royal Kraal to do just that.

He had however, been warned that Dingane who had come to power following the murder of his half-brother Shaka was not someone to be trusted but being a man of honour himself, he assumed Dingane was also.

On 6 February 1838, Retief and his party of 100 men including coloured servants visited Dingane to formalise the treaty between them. Both men appeared pleased with the agreement and following the ceremony Dingane, who had earlier persuaded his visitors to put aside their rifles and other weapons invited them to witness performance by his warriors. Lulled into a false sense of security by Dingane’s more than generous hospitality, Retief agreed.

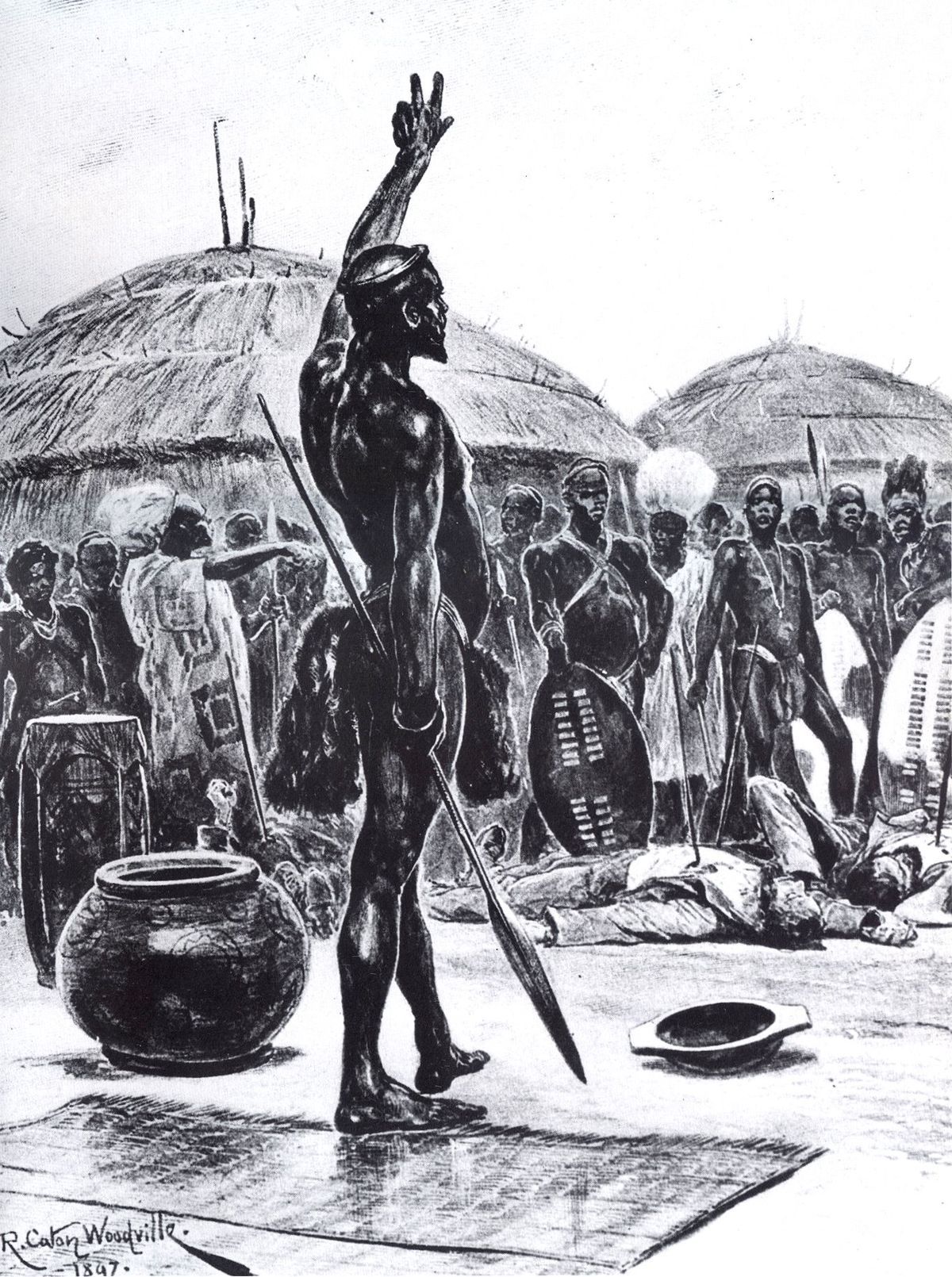

It was to prove a tragic error of judgement for no sooner had they gathered than Dingane rose to his feet and accusing them of witchcraft ordered his warriors to take the sorcerers and kill them. They were then dragged to a nearby hillside and brutally clubbed to death. Retief was the last to die forced to watch not just his friends but his own son’s death, a slow, agonising death. The bodies were then left unburied to be pecked at by vultures. Except Retief’s corpse that is, which Dingane had mutilated so his heart and lungs could be removed and delivered up to him in his enclosure.

Having disposed of Retief and his party Dingane now intended to do the same to the Boers on whose behalf he had been negotiating. He ordered his warriors to attack their encampments which they proceeded to do with great violence and without mercy killing 534 Boer men, women, and children.

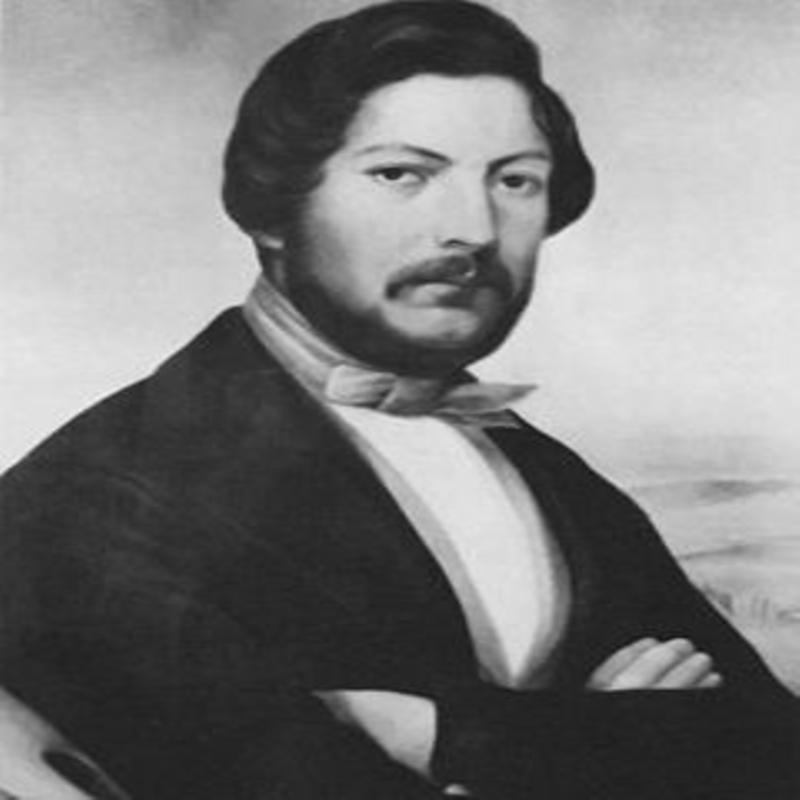

The so-called Weenen Massacre had left the remaining Voortrekkers frightened and in some disarray. When Andries Pretorius, a scion of one of the most respected Boer families and a man who had long agitated for the Boers to establish their own republics and was leading his own column towards the Modder River agreed to come to their assistance they were only too happy to cede control to him. It was a wise decision for he not only exuded confidence but having lost their own leaders in the murder of Retief and his party they had nowhere else to turn. He was also determined to take the fight to the enemy.

Pretorius was careful to first arrange an informal alliance with Dingane’s great rival the Prince Mpande who had earlier fled the Zulu nation with around 15,000 warriors. He now had on his side a man with whom he could replace Dingane, but to first oust him remained difficult. Various attempts to assassinate him had failed while penetrating the Royal Kraal heavily guarded as it was and protected by terrain difficult to navigate and overcome had failed.

In any case, Pretorius wanted to defeat Dingane’s Impis in battle not only to avenge the massacres they had been responsible for but to undermine their leader’s

authority but he had neither the manpower nor firepower to do so in the open. He had to coax them into attacking him behind a strongly fortified defensive position. But Dingane was no fool and knew this too. He ordered that his Impi not attack the Boers when encamped but instead lure them into an ambush.

Pretorius organised a column to march on the Royal Kraal at UmGunddlovu. He had under his command 464 Boer commando armed with muzzle loading rifles, 2 cannon, and 200 coloured servants who though not armed would assist in the reloading of guns and distribution of ammunition. There were also a small number of women and children present of which one Paul Kruger, the future President of Transvaal during its war with the British would like to remind people of at official functions.

Pretorius would threaten the Royal Kraal but not attack it; to do so would mean fighting in open country and the possibility of being outflanked and overwhelmed - the Zulu, he insisted, must attack them. His Officers were divided as to the strategy. Some fearing the prospect of a static battle preferred the mobility of cavalry believing they could disperse the Zulu and put them to flight before they could organise and form up, but this tactic had failed in the past. He, unlike them, understood the effectiveness of concentrated firepower against the massed ranks of an enemy. So did the Zulu, but their blood was up. They had failed to lure the Boers into an ambush now they would fall into their enemy’s trap.

The Zulu General was Ndlela KaSompisi who had previously led an unsuccessful attack on a fortified laager and knew the difficulty it entailed but his relationship with Dingane was a troubled one. His commitment to the cause of victory may not have been all that it should.

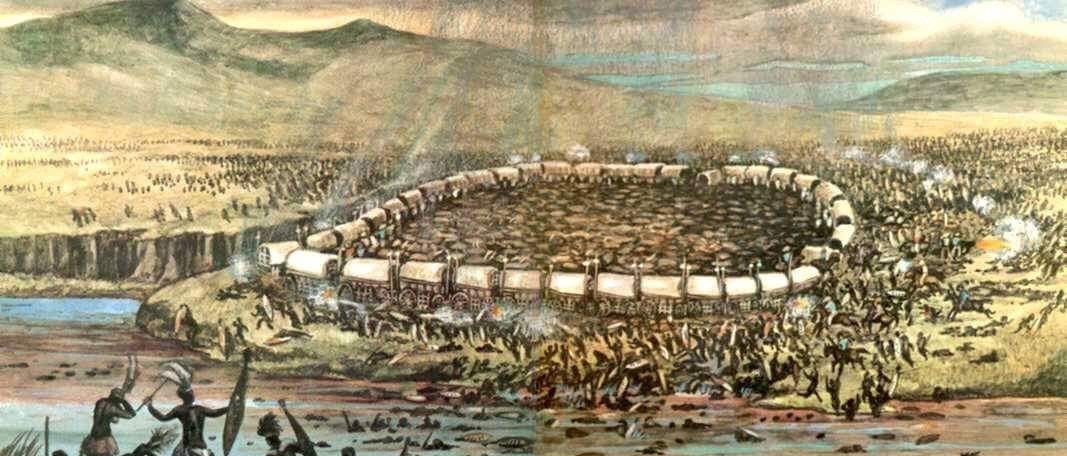

Aware that large Zulu formations were present in the area and monitoring his movements on 15 December, Pretorius, laagered his camp on the banks of the Ncome River; the position was well chosen, it was on the bend of the river where both his rear and flanks were protected by water while the ground over which any attacking force would have to advance was flat and open.

Pretorius had his 64 heavy wagons pulled closely together until so tightly packed there was barely any daylight between them, where there was a gap, wooden barriers were erected to prevent any incursion but in such a way they could be removed quickly if required. The cannons were placed at either corner of the laager.

The Zulus were indeed massed near the laager, as many as 15,000 of them and for them it made an irresistible target. Meanwhile, the Boers fearing a night attack ensured their camp was well lit with oil lamps, a mixture of the darkness and the mist that soon descended made it an eerie sight.

As the new day dawned it was clear battle was imminent, Jan Gerritze Bantjes a close associate of Pretorius described the scene:

“Sunday, December 16 was like being new born for us – the sky was clear, the weather fine and bright. We hardly saw the twilight of the break of day or the guards, who were still at their posts and could just make out the distant Zulus approaching. All th patrols were called back into the laager by firing alarm signals from the cannons. The enemy came forward at full speed. Their rapid approach (though terrifying to witness due to their great numbers) was an impressive sight.

The battle now began, and the cannons unleashed, such that the battle was fierce and noisy, even the discharging of small arms fire from our marksmen on all sides was like thunder.”

The Zulus came on, wave after wave of them, but unable to penetrate the laager and come to grips with the enemy they found their assegais or short stabbing spears, an excellent weapon in close quarter combat, worse than useless. Still, they swarmed around the laager but for as long as they did so the Boers mowed them down in their hundreds.

Four times the Zulus attacked and four times they were repulsed yet it appeared they had no other strategy than to continue doing so; with the bodies piling up despair began to set in and increasingly exhausted each attack was less furious than the last.

Pretorius also had problems of his own; he knew ammunition was running low and that if the rate of fire was not sustained they could still be overwhelmed, so he ordered a mounted assault to blunt the enemy attack, one he would lead himself. It was a risk but a necessary one and he knew the Zulus were nervous of horses – he was right. There was little resistance as the horsemen approached and they soon began to flee first hesitatingly and then in great haste. The Boers would pursue them for many hours and some distance from the camp.

The confidence Pretorius had displayed in the effectiveness of a well-fortified laager and the courage and marksmanship of his men had been borne out. He had achieved an astonishing victory against overwhelming odds; and for the Boers at least the Battle of Blood River had been an almost bloodless affair, just three men wounded among them Pretorius himself, stabbed through the hand with an assegai.

For the Zulus who had also displayed great courage, it was very different. They had paid a fearful price; some 3,000 dead lay around the laager with a similar number wounded and incapacitated. How many were killed in the pursuit remains unknown.

Prayers were said that night in the Boer camp for their triumph and their deliverance. They were a chosen people and they thanked God for making them so. The Battle of Blood River would be commemorated annually thereafter as the ‘Day of the Covenant.’

Dingane was furious, he had warned against attacking the Boers in laager and not just his advice, but his orders had been ignored with disastrous consequences. When Pretorius arrived at the Royal Kraal four days later, he found it abandoned. On 2 1 December, they recovered and buried the remains of Retief’s party. They also found the treaty signed by Dingane, their anger at the betrayal was palpable.

Dingane would not be deposed until January 1840 when in alliance with the Boers his half-brother Prince Mpande defeated him at the Battle of Maqongqe. Dingane escaped with his life though it would be a temporary reprieve only. Before fleeing into Swazi territory he had Ndlela KaSompisi strangled to death in a last act of vengeance. He was himself murdered soon after.

On 10 February 1840, the new Zulu Chieftain Mpande and Pretorious signed an agreement that saw the land west of the Tugela River become the Boer Republic of Natalia with the victor of Blood River as its first President. It would not survive long, three years later it was annexed by the British and the Boers were forced to move on once more.

They would in time find their place but the events surrounding Blood River, the deception, the betrayal, the murder, and the sense of Divine Mission confirmed by their triumph would create a legacy that not only solidified as the determinant of future events but remains to this day like the ashes of dead martyrs strewn upon the altar of thwarted dreams and ambitions.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, War

Share this post: