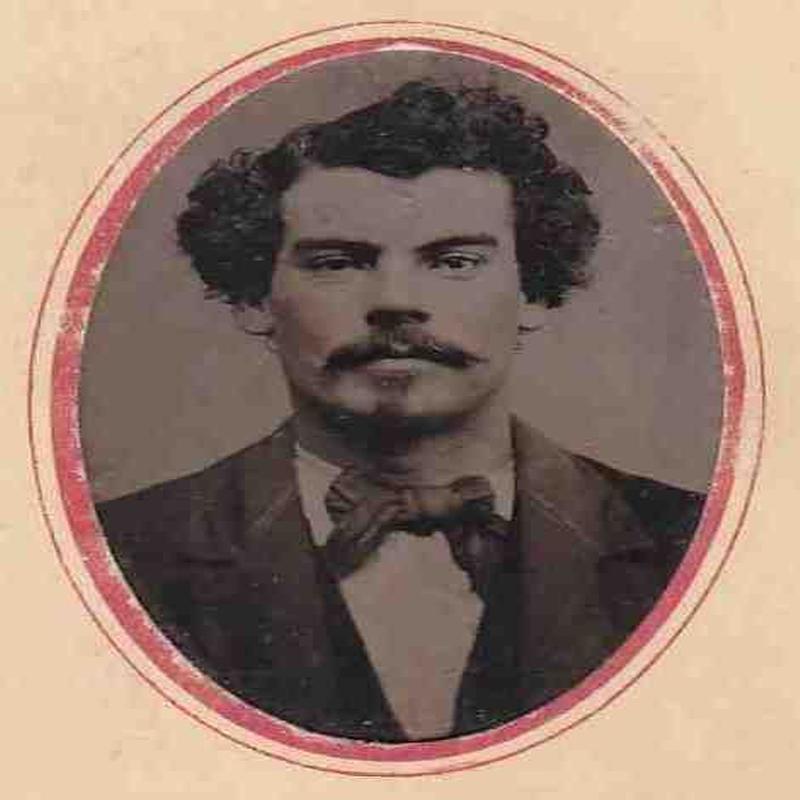

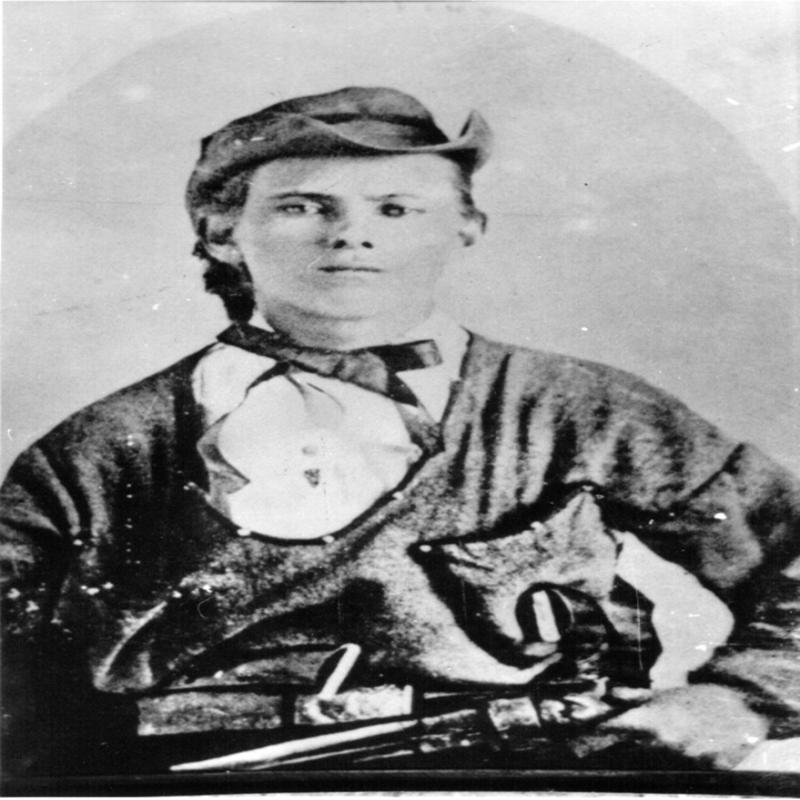

Bloody Bill Anderson

Posted on 19th March 2021

William Thomas Anderson was born in Randolph County, Missouri in 1837, the exact date and location of his birth, remain uncertain. He was the son of a hatter who an enthusiastic pro-slavery man would often abandon his family for long periods to go gold prospecting. As a result, it became the responsibility of the young William, known as Bill and his brothers to take care of the family.

It was a large and insular family and bonds of affection rarely strayed beyond it. When his mother was killed in 1860 after being struck by lightning, Bill took it upon himself to tend to the needs of his three younger sisters of whom he was particularly fond.

By 1858 the Anderson’s had moved to the town of Council Grove in Kansas, a predominantly slave holding region. The family soon earned a reputation for cattle rustling and horse theft. Bill, who described himself as a horse trader found it far more lucrative simply to steal them. Indeed, the Anderson boys soon became feared for their violence and late in 1858, Bill’s older brother Ellis was forced to flee the area after he was accused of killing an Indian.

In March 1862, his father who had always been vocal in his pro-slavery views and in his support for the Confederacy was shot and killed by an anti-slavery neighbour.

Bill and his brothers were quick to avenge their father’s murder and not only was the man responsible killed but also a Union soldier who had tried to intervene. Now a wanted man Bill made the decision to flee and join up with William Clark Quantrell’s Confederate guerrillas operating in Missouri. This was not his first attempt to do this. On a previous occasion he was thwarted when along with his brother James and a friend Judge Baker, they were intercepted by Union troops. Bill and James managed to escape but Judge Baker did not. He was later released after having professed his loyalty to the Union but fearing that he would lose his position Judge, Baker now turned against his friends issuing a warrant for their arrest. In revenge the Anderson brother’s lured Baker and a colleague to a local store where ambushed the two men were forced to seek shelter in the cellar. Bill ordered the store set alight and both men were burned to death.

Following the murder of Judge Baker, Bill and his brother James went into hiding until in July 1862 along with another friend Bill Reed they formed their own gang and embarked upon a spree of robberies. It would prove a lucrative new career but he still desired to fight for the Confederate cause. At last, in January 1863, he crossed over into Missouri to join up with Quantrell’s Raiders.

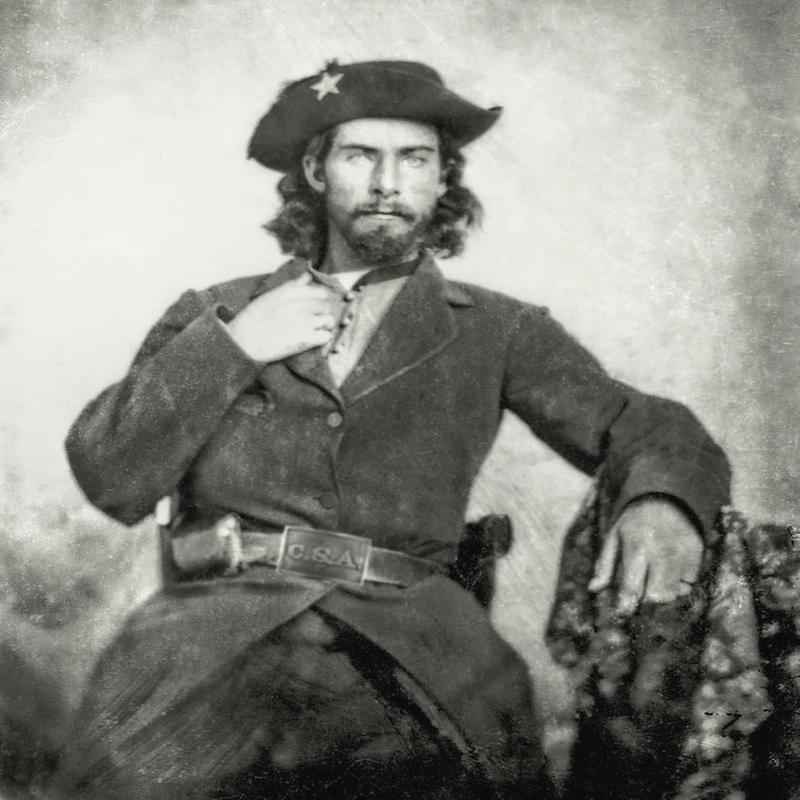

Since July 1861, when General Sterling Price’s advance into Missouri was repulsed there had been no Confederate military presence in the State and defence of the Rebel cause had fallen to bands of guerrillas known as Bushwhackers and the most notable of these was that led by William Clark Quantrell.

He and Anderson had encountered one another before. Indeed, Quantrell, who did not consider himself a guerrilla and did in fact hold a commission in the Partisan Rangers, had previously rebuked Anderson for robbing known Confederate as well as pro-Union supporters. He had done this in front of others, and it had caused a great deal of resentment, since when the two men had grown to dislike each other intensely.

The Confederate guerrillas had a great deal of support in Missouri especially in Jefferson County where they were provided with supplies and a network of safe houses. Anderson’s sister’s, along with many of the other women in the County were active in providing them with information.

To deprive the guerrillas of succour in the summer of 1863, the Union Commander in the State, General Thomas Ewing issued Order No 11 which saw the arrest of the female relatives of known Confederate guerrillas. The women were imprisoned in a rickety three-storey building on Grand Avenue in Kansas City. Not long after their incarceration the building collapsed killing several the women one of whom was Bill Anderson’s sister, another of his sisters was maimed.

The rumour soon spread that the building had been deliberately sabotaged and that Union troops were murdering their women. Upon learning of the fate of his sisters Anderson went into a rage that it was said never left him. From that point on he would respond to criticism by saying, “I enjoy killing, I can never kill enough.”

Quantrell, who had long been planning an attack on the pro-Union town of Lawrence now used the death of the women in Kansas City to whip his men into a frenzy of vengeance.

Lawrence was the centre of the anti-slavery movement in Kansas and since the beginning of the Civil War it had grown rich on the plunder of stolen Southern property and goods. It also served as the base from which pro-Union guerrillas, or Jayhawkers, operated, and was the home of Senator James Lane a particular Southern hate figure much reviled for his anti-slavery views and for the forced removal of Southern sympathisers from their homes and the confiscation of their property.

Quantrell also had a personal score to settle, prior to the outbreak of the war he had been wrongly accused by the town authorities of murder and had been forced to flee leaving all he possessed behind. Lawrence then was a thorn in the side of the Confederate cause and Quantrell was determined to eradicate it.

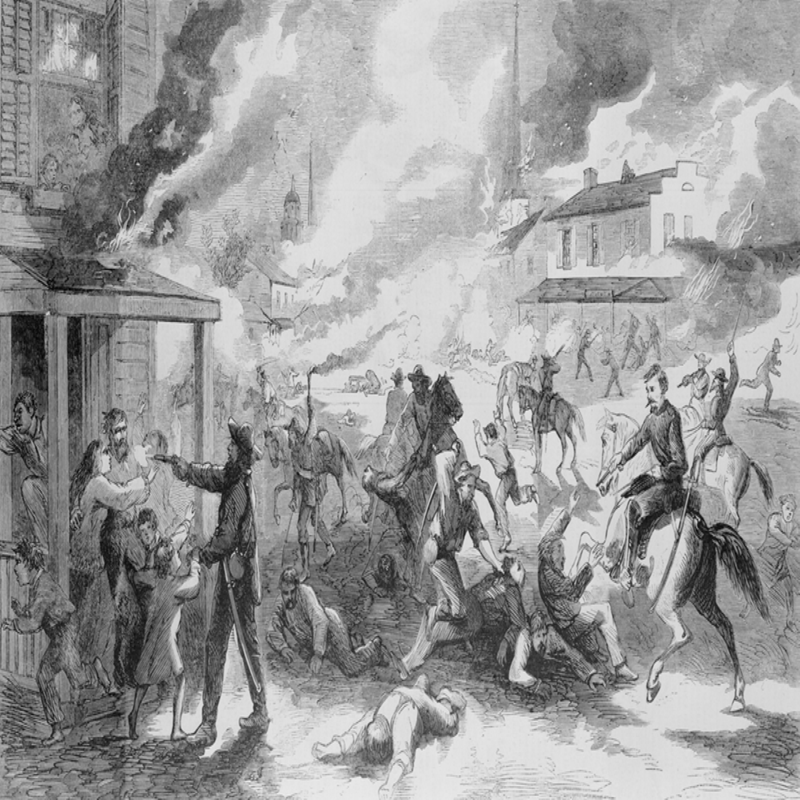

In the early hours of 21 August 1863, following a forced night march, Quantrell led 450 men in a well-co-ordinated attack upon the town. The small Union garrison stationed there was taken completely by surprise and quickly overwhelmed.

What followed was an orgy of violence as any black man encountered was killed out-of-hand. Quantrell then ordered all the men and boys rounded up before having them shot and clubbed to death as their women were forced to look on.

Quantrell had specifically ordered that no woman was to be harmed but they were roughly handled, and many were ravaged. The bodies of the murdered were then piled in the main street and set alight before the bank was robbed, homes looted, and the town torched. Some 183 men and boys had been killed, the youngest aged just seven.

Senator Lane had barely escaped with his life fleeing in his nightshirt into a cornfield where he remained until the raid was over.

Anderson, who despite their antipathy toward one another Quantrell had made one of his lieutenants had been personally responsible for killing 14 men and boys at Lawrence, and as usual he took their scalps as a memento.

Quantrell and his men were closely pursued by Union cavalry following the attack on Lawrence and were forced to fight a series of pitched battles in which 40 men were killed. The pressure was building and when the Union flooded the Kansas-Missouri border with thousands of troops the Confederate guerrillas were no longer able to operate and Quantrell and Anderson were forced to flee with their men to Texas.

On their march to Texas, they stopped off at Baxter Springs in Kansas. Quantrell was aware that Fort Blair nearby was garrisoned by 70 or so negro soldiers, this he considered an affront to the white man’s dignity and determined to expel them. His attack upon the fort was repulsed however and he was forced to withdraw but during their retreat they stumbled upon a unit of black Union soldiers on their way to the fort. In a quickly organised ambush they killed 100 of 103 men, and those few who were captured and disarmed were summarily executed.

In the wake of the ambush Bill Anderson’s blood was up, and he demanded they resume the attack on Fort Blair. Quantrell disagreed saying they did not have the time and ordered him to withdraw. A clearly disgruntled Anderson demurred but he was getting tired of being told what to do.

During their time in Texas the relationship between Quantrell and Anderson worsened as they argued repeatedly with Quantrell accusing Anderson of being little more than a thief and a murderer and spreading the rumour that he alone was responsible for the worst misdeeds of the Missouri-Kansas guerrilla war.

The dispute between the two men might have spiralled out of control had Anderson not been distracted by the attentions of a saloon girl named Bush Smith whom he was to later marry.

In early October 1863, Quantrell expelled one of Anderson’s men for theft and when he later tried to return Quantrell had, him shot. It was the final straw.

On 12 October, Anderson met with General Samuel Cooper to whom he accused Quantrell of ordering the death of a Confederate Officer. Quantrell was promptly arrested though he was later released following inquiries.

By the spring of 1864, Anderson was back in Missouri in command of his own band which he named the First Kansas Guerrillas. It was over the next few months that Bill Anderson would acquire his reputation for brutality and write his name in blood upon the history of the American Civil War.

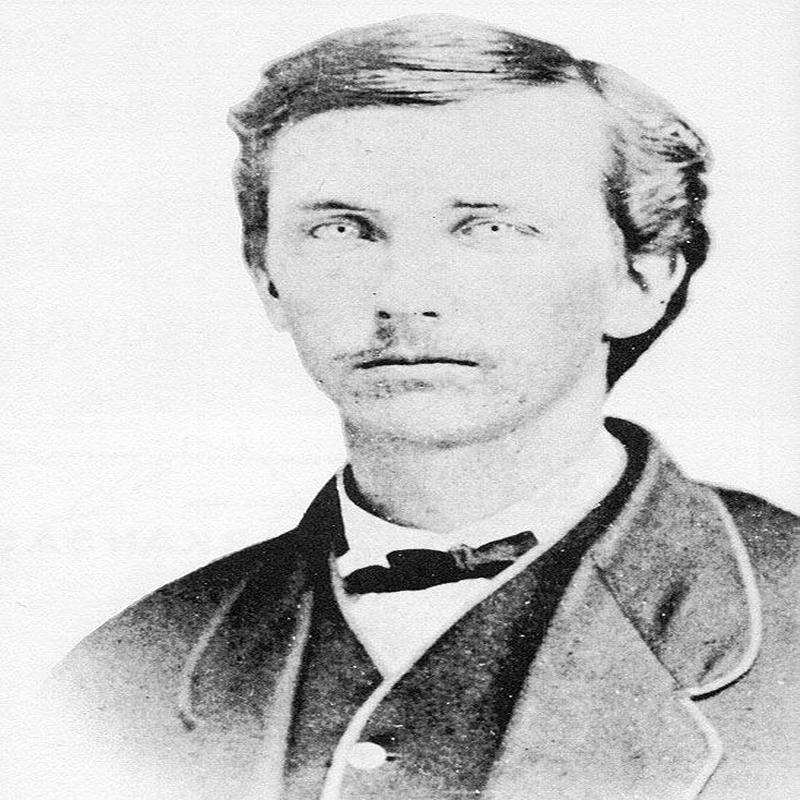

On 12 June 1864, he ambushed 15 men of the Missouri State Militia killing 12. The following day he attacked a Union wagon train killing 9 soldiers. On both occasions the dead men were robbed, scalped, and their bodies mutilated. His chief lieutenant, eighteen-year-old Archie Clement, known as “Little Arch” because he was only 5 feet 2 inches tall, was particularly fond of mutilation and liked to torture captives by slowing slicing off their ears.

It was around this time ‘Little Arch’ recruited to the gang his boyhood friend, the sixteen-year-old Jessie James and his older brother, Frank. When there were not Union troops to engage Anderson and his men busied themselves robbing and looting the homes of known anti-slavery men and executing their male occupants. It wasn’t long before Anderson was the most feared guerrilla leader of them all. He was referred to in the press as the Devil and soon acquired the name “Bloody Bill” Anderson.

On 15 July, Anderson entered the town of Huntsville with the intention of robbing the bank and killing the pro-Union Sheriff there. He proceeded to do both making off with $40,000 though in a rare act of generosity he returned some money that had been stolen from a friend. On 23 July, they raided the town of Renick, tearing down telegraph wires before moving onto Allen, Missouri, to confront the small Union garrison there. They refused to fight however instead barricading themselves in the small fort, so Anderson had to settle for shooting dead all their horses.

In an attempt to halt Anderson’s activities a force of 800 men was gathered to track him down. In response Anderson abducted the Union Commander’s elderly father who he had tortured close to death before releasing him as an example of what would happen to others if they continued their pursuit. The mostly State Militiamen who had been assigned the task of hunting Anderson down lacked resolve, they had no desire to see their own families fall victim to such terror. So Anderson was able to continue his raids.

On 30 August he captured a steamboat and used it to attack other vessels bringing river traffic to a standstill.

But in a series of engagements he lost 11 men in a single week and it had put him in a dark mood.

On the afternoon of 27 September 1864, Bloody Bill and his men arrived at the town of Centralia, primarily to forage for supplies, tear up railway lines, and destroy the station and telegraph office.

As his men went about brutally dispossessing the town’s populace, he noticed the railway timetable indicated a train was due. He decided to remain longer than he had originally anticipated so as to rob it.

Aboard the train were 25 unarmed Union soldiers on their way home on furlough. The Officer commanding Lieutenant Peters recognised Anderson standing on the station platform as the train drew up. Without thinking and certainly without regard for the safety of his men, Peters threw a blanket over himself and as soon as the train stopped leapt off and hid underneath it. Sadly, for the unfortunate Peters he was spotted and Anderson’s men pulled him out from beneath the carriage, laughing and jeering as they did so. Yelling and struggling furiously Peters managed to break free. Now he was running for his life. Anderson called his men off from the pursuit and taking careful aim pumped six bullets into the back of the desperate, terrified, fleeing Peters. It was a portent of what was to come.

Boarding the train Anderson could hardly contain his delight as he laughed and exchanged jokes with his men. The Union soldiers were ordered off the train, lined up, and made to strip. The guerrillas regularly wore stolen Union uniforms to confuse the enemy during their raids. Anderson then walked over to where his horse was tethered and removed a rifle and a bag of pistols. He then proceeded to stroll up and down the line of helpless prisoners randomly shooting each one between the eyes. Witnessing this the prisoners began to panic, some fell to their knees and begged for their lives, others made supplications to their God, many simply cursed. It was all to no avail, Anderson shot them all dead except one, who was severely beaten but kept alive to be used as a hostage, he later escaped. Once they had been killed the mutilations began.

One particularly eager participant it was remembered by those present was the young Jesse James who along with his brother Frank and the Younger’s would later make up the notorious James Gang.

After the murders Anderson robbed the male civilian passengers on the train but permitted them to go free and then set the train alight. Railway tracks were then torn up derailing a freight train coming up behind.

Having been alerted of the events taking place at Centralia by late afternoon 150 men of the 39th Missouri Volunteer Infantry had arrived. Surveying the grisly scene and seeing some guerrillas in the distance they immediately set off in pursuit, but they were being led into a trap. Forced to attack a guerrilla defended position uphill they were unaware that Anderson had led his men around their flank, and he now assaulted them from the rear. It was another massacre as 125 Union soldiers were cut down and killed for the loss of just 5 of Anderson’s men.

As before, the mutilations began once the killings had ceased with the dead men being scalped, castrated, and having their ears and noses cut off to be kept as trophies. In some cases, they were even decapitated. The few survivors were tortured but left alive as an example to others.

The savagery of the events at Centralia and in its immediate aftermath shocked the North, some people even suggested the area be abandoned and for a time rail traffic in Missouri ceased altogether. Unionists in the State wanted to exact revenge and several known civilian Confederate sympathisers were murdered, and the pro-slavery town of Rocheport burned to the ground. The Union Commander in the State General Clinton Bowen Fisk with some difficulty managed to curtail the reprisals, however.

Instead of abandoning the State the Union response was to flood it with even more troops and these were no longer green volunteers and State Militia of before but soldiers who were veterans of the war in the East. They were also provided with artillery for the first time and had appointed the experienced army scout Samuel P Cox with the specific task of hunting Anderson down and provided him with an elite unit of troops with which to do it.

Following Centralia, Anderson travelled to meet with General Sterling Price whose recent attempt to invade Missouri had once again been repulsed. Despite being appalled at the sight of the scalps that adorned Anderson’s saddle he endorsed his actions and issued him with instructions to continue to disrupt Union rail communications. He also commissioned him a Captain in the Confederate Army which delighted him.

Upon leaving camp Anderson ignored his orders and instead travelled to the town of New Florence where he sought to kill some wounded Union soldiers he had learned were being treated there but he was prevented from doing so by Confederate soldiers stationed in the town.

Frustrated he moved onto Glasgow where he took captive the wealthiest man in the town, a known pro-Union man who had many years before freed his slaves. He beat the man severely and publicly humiliated him before going on to rape his 13-year-old female black servant. Paid $5,000 by the townspeople he agreed to release the man, but he later died of his injuries. His men then returned to his house to rape his other female servants.

A woman who was resident in Glasgow and had known the Anderson family from before the outbreak of war and despised them now rode in haste to the camp of Samuel P Cox. She breathlessly informed him that not only had Anderson been in Glasgow but that she knew where he and his men would be resting. Cox was at first suspicious of the report but reassured by others of the woman’s good character he set off in pursuit.

Samuel P Cox was a proficient scout and veteran Indian fighter who had ridden the trails with the legendary Kit Carson. He knew the Missouri terrain well and he understood guerrilla tactics. He travelled to within half a mile of Anderson’s camp near the town of Orrick where he deployed his men at the end of the road leading to it, and along either side. He then sent a small detachment under a Lieutenant Baker to advance upon the camp and lure Anderson’s men out. The plan worked like a dream. In no time at all Baker was seen to be fleeing down the road with Anderson in hot pursuit.

Unlike in other engagements when State Militiamen and raw recruits had so often panicked and ran, Cox’s troops were veterans who maintained their discipline and held their fire until Anderson’s men were well within range and had no prospect of escape.

Once the firing began Anderson quickly realised that he had been lured into a trap but nonetheless ordered his men to continue the charge and cut their way through. Instead, they retreated with as always Anderson himself the last to leave the field. It seemed for a moment that he might make his escape but suddenly his horse slowed, he bent double, and slowly fell from the saddle. He had been shot below the right ear and death would have been almost instantaneous.

For such a perfectly laid trap the brief engagement that followed had wreaked little havoc with only two guerrillas and one soldier being killed but Cox had got his man.

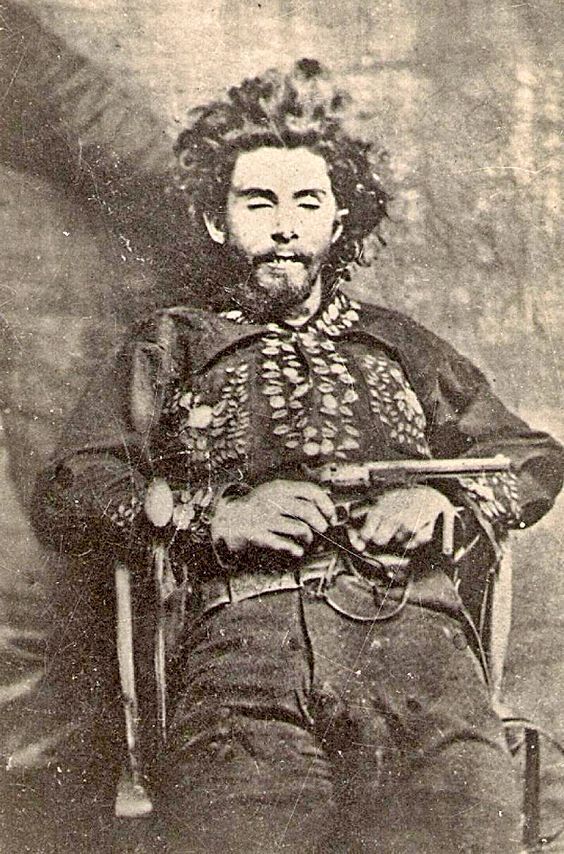

Anderson’s body was taken to the nearby town of Orrick where it was photographed before being decapitated with a knife. His head was then placed on a telegraph pole as a warning to others and his body urinated upon before being tied to the tail of a horse and dragged through the streets of the town.

The bitter, fratricidal and internecine warfare that took place in the Border States and elsewhere is an aspect of the American Civil War that is now too easily overlooked in favour of the manoeuvrings of great armies. But it was a war that divided families, set neighbour against neighbour and destroyed communities; and as all civil wars do it provided the opportunity to pursue grudges, avenge sleights and right perceived wrongs.

In the Missouri-Kansas region alone it accounted for 25,000 deaths most of them civilian.

Rumours have persisted since that Bloody Bill Anderson survived the ambush at Orrick and that he may in fact have escaped to and settled in Salt Creek, Texas. A man fitting his description died there on 2 September 1927. On his bedside table was a photograph of three young women later identified as Anderson’s sisters. If so he would have been 89 years of age. The likelihood remains however that if it was an Anderson at all it was one of his brothers.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: