Catherine de Medici: Madame Snake

Posted on 8th May 2021

Caterina Maria Romula di Lorenzo de Medici was born on 13 April 1519, her parents were Lorenzo de Medici, Duke of Urbina and Madeleine de la Tour de Auvergne, Countess of Boulogne. She was then, no fault of her own, a child of one of the most loathed families in Europe the Medici, who did not just govern Florence, provide Popes and patronise the arts but also when not making war on their neighbours fleeced the people to line their own pockets. Worse in the eyes of many they were the descendants of money-lenders with no status other than that purchased with gold coin.

In 1527, when Catherine was aged just eight the Medici were temporarily overthrown by the mob and forced to flee Florence in some haste and to make good their escape, they were willing to leave Catherine behind as a hostage.

The rebellion was soon crushed by the forces of Giulio de Medici, the recently elected Pope Clement VIII and Catherine’s parents were restored to their previous position but although she had remained unharmed it had been a frightening experience and one she never forgot.

CCatherine was sent to Rome to be under the protection of her uncle the Pope and there she remained until 1533 when aged 14 she was betrothed to Henry of Orleans the second son of King Francis I of France. Catherine’s appeal as a bride was political and little else for even as a young girl she was considered plain and somewhat dull. A contemporary wrote of her: “She was so very small and slender with fair hair, and thin but not pretty in the face, with the eyes peculiar to all the Medici.” They were said to protrude, and the bug-eyed Medici slur was an insult commonly heard in the Royal Courts of Europe.

Even so, despite her physical disadvantages Catherine was determined to make a good impression on a hostile, French Court and employed an Italian artisan she knew well from her time in Rome to devise something that would disguise her lack of stature and make her appear grand. What he designed were the first high-heeled shoes which not only caused a sensation but changed the course of fashion forever.

Nonetheless, being an Italian and even worse a Medici she was not popular in France, and she did little to endear herself to the people by often speaking in her native tongue, scorning French manners and refusing to eat French food instead employing Italian cooks. Little wonder that she soon became known as “that Italian Woman.”

In 1536, the King’s eldest son died making Catherine’s husband heir to the throne but despite her elevation in status her marriage was not a happy one. She was not loved by a husband who often neglected her and as a result she became ever closer to the elderly King Francis. When he died in 1546, she was devastated and the fact that she was now Queen did little to lift her mood.

Her husband Henry spent most of his time with his mistress Diane de Poitiers who at 38 was almost twice his age and with whom he was utterly besotted. She allowed him to be free with her body including perching upon her lap and fondling her breasts in public. Indeed, it was said that she treated the King like a child and ruled him with a rod of iron.

Henry had an infirmity of mind it was said, and it was not he who ruled in France but his mistress. It was a mental lassitude that was to infect all of Catherine’s children, and she was to bear ten during her lifetime but then it was her Royal duty to do so, and she did it with aplomb. The humiliation of being side-lined in her husband’s affections she bore with a quiet fortitude.

On 1 July 1559, Henry was severely injured in a jousting tournament when the lance of his opponent pierced his helmet, and he was knocked from his horse. When his helmet was removed such were his injuries, splinters had pierced both his eyes and brains and blood covered his face, that both Diane whose colours he had been sporting and Catherine fainted. His wounds were dressed but despite showing signs of recovery over the next few days he finally succumbed to his wounds dying on 10 July.

Catherine had earlier read the prophecy of a doctor named Nostradamus who had appeared to predict the tragedy: “The young lion shall overcome the older one, on the field of single combat in a single battle, he shall pierce his eyes in a golden cage, and then he shall die a cruel death.” She was impressed and not long after appointed Nostradamus Court Physician and unofficial soothsayer. Henceforth, she would regularly consult the seer in matters regarding her family.

Following Henry’s death their son Francis, aged 15, was crowned King Francis II with Catherine as Regent, but within a year he too was dead. It now fell to her second son to be crowned Charles IX; few however could be in any doubt who was really in charge. Catherine dominated the French Court though she did so through cunning and guile rather than the charm and force of personality that so marked out the reign of her contemporary Elizabeth I in England.

She never acquired the love of the people and only the grudging respect of many of those at Court, the Italian grandeur of which she was so often accused did little to enhance the already most glittering Court in Europe, and she was criticised for squandering the Royal Purse on patronising the arts with little to show for it.

France in the 1560’s was blighted by the bloody wars between the majority Catholic population and the Huguenots or French Protestants.

Catherine had no love for the Huguenots, but she was first and foremost a pragmatist who was prepared to endure even further unpopularity if by agreeing a peace deal with them it strengthened her position at Court against her enemies, and she had many.

The Peace of St Germaine signed in 1570 brought the most recent conflict to an end but it was to be a tenuous peace. The proposed marriage of Catherine’s daughter Marguerite de Valois to the Huguenot Prince Henry of Navarre was intended to seal the peace but to a great many Catholics in France the mere presence of Protestants in their country was intolerable and a marriage between the two respective Royal Households simply unthinkable. Catherine however remained determined that the marriage should go ahead.

Most of the leading Huguenots were in Paris for the wedding including their military commander Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, a formidable enemy who had long been a thorn in the side of the Catholic majority. Catherine was put under great pressure particularly by the powerful Guise family to use this opportunity to eliminate their most dangerous opponent, but she remained noncommittal.

After the wedding ceremony the most prominent Huguenots remained in Paris to discuss outstanding aspects of the peace treaty. On 22 August, whilst these negotiations were still taking place de Coligny was shot in an assassination attempt. He survived but had been severely wounded. Whether she had planned to murder de Coligny or merely panicked remains uncertain but Catherine, fearing that her complicity in a plot might be discovered urged her nobles to kill all the Huguenots still in Paris but the nobility who had long resented Catherine’s pre-eminence now refused to do so insisting that only the King had the authority to order such.

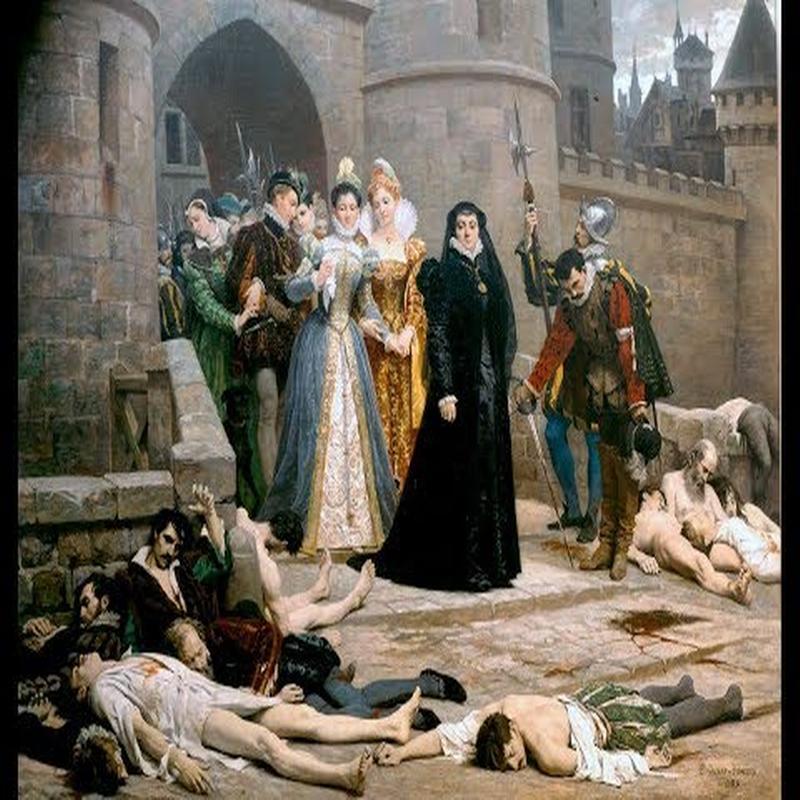

On the evening of 23 August, she visited her son Charles and begged him to order the death of all the Huguenots and it was an indication of how hard she pressed him that eventually he shouted in exasperation: “Well then, so be it! Kill them! Kill them all! Don’t leave a single one alive to reproach me." Years of enmity and hatred were now unleashed in a terrifying orgy of violence and murder.

Huguenot homes throughout the city were burned, shops looted, and those areas of Paris known to be populated by both Protestants and Jews were cordoned off and their inhabitants butchered. More than 4,000 people were killed in Paris alone but the killings did not stop there and had already begun to spread throughout the country.

Catherine realising the enormity of what she had started issued a Royal Decree ordering that the killing should cease but no effort was made to enforce it and the massacres soon spread to other major towns such as Rouen, Bourges, Orleans, Lyons, and Bordeaux.

The killings were to continue for another three months with as many as 50,000 Huguenots slaughtered while thousands more fled abroad mostly to England.

On 24 August, Gaspard de Coligny who had survived the first attempt on his life was dragged from his bed and butchered his naked body thrown from the window onto the street below.

As the killings continued Henry of Navarre, unable to do anything to help his people and fearing for his own life was forced to convert to Roman Catholicism. As he knelt before the altar in supplication Catherine was heard to laugh. It was an incident widely reported by those foreign Ambassadors present further cementing her reputation as that now 'Wicked Italian Woman.' The Catholic world meanwhile rejoiced at what was to become known as the St Bartholemew’s Day Massacre and Pope Gregory XII ordered that Te Deums be sung and medals struck to commemorate the event.

Catherine was delighted to take the plaudits especially as despite her half-hearted attempts at peace-making she had more than once displayed her hostility towards the Huguenots having previously withdrawn all their rights of worship and forced their Ministers to flee the country on pain of being tried as heretics; but then the fact she faced both ways at once came as no surprise to most for she flattered to deceive, lied when it suited her and regularly manipulated others to do her bidding. Already disliked by her people her artifice and cunning only increased their mistrust and antipathy. Her nickname of Madame Snake had been well earned.

But her constant wavering between open hostility and reconciliation with the Huguenots only alienated the powerful Guise family who were posing a serious threat to her grip on power and their hard-line Catholicism was winning them support within the country, so much so that they were effectively establishing a State within a State.

Despite having effectively ruled France for almost thirty years Catherine began to flounder as she struggled to understand the depth of hatred so many felt towards her personally, and she never could grasp the complex theological issues that dictated so much of French policy. For the first time perhaps, she began to think herself out of her depth.

In 1574, Charles IX had died, and her third son Henry succeeded to the throne. It came as a relief to Catherine for he was not a child but 23 years old, and far and away her favourite but he also suffered from the same mental fragility that had blighted the lives of all her children and he was to prove indolent, lazy, often distracted and all too easily swayed.

Indeed, as time wore on it became increasingly apparent just how foolish a young man Henry was. When he wasn’t dressing up and promenading for the benefit of his many courtiers, he was playing frivolous games with his friends. He would often be found in prayer, though no one was able to quite ascertain exactly what he was praying for? Perhaps a child, for though he had been married for a number of years there was little indication that he was about to add to the dynastic brood.

No doubt urged to do so by his ambitious friends, Henry would seek to assert his authority from time-to-time and make a pretence at being a working King of France. His interference however only served to prevent Catherine from being able to adopt a coherent policy and increased the power and influence of the Guise family.

Catherine’s long struggle to sustain and preserve the Valois Dynasty was under serious threat and beginning to unravel. Only her youngest son, Francis, Duke of Alencon, showed any promise but this was often in opposition to his mother’s policies. He had allied himself to the cause of the Huguenots as a bulwark against the ambitions of the Duke of Guise and as a result of his support on 6 May 1576, Catherine was forced to sign a humiliating peace deal that damaged her prestige but at least brought some stability to the regime.

Throughout the years following Francis was to continue to plot and scheme against his brother’s rule but despite his disloyalty he remained the best hope for the Valois Dynasty. When he died of consumption in June 1584, Catherine was devastated. She wrote:

“I am so wretched to live long enough to see so many die before me, though I realise that God’s will must be obeyed, that He owns everything, and that he lends us only for as long as he likes the children whom He gives us.”

Under Salic law a woman could not inherit the throne and so with her youngest son dead and the King unable, or uninterested, in siring children the next in line was her son-in-law and former enemy, Henry of Navarre. But it was not her relationship with Henry, which had improved somewhat since his conversion to Catholicism and the dark days of late summer 1570, but the behaviour of his wife, her daughter Marguerite that was the problem.

Marguerite of Valois had no great affection for her husband and appeared incapable of fulfilling the role of dutiful wife and future Queen. She would frequently elope with a lover before returning to the Royal Court as if nothing had happened before then proceeding to embarrass and humiliate Henry at every turn. In 1585, she abandoned her husband once again this time vowing never to return.

Ensconced in one of the many chateaus she had received as a wedding gift, Marguerite wrote to her mother begging for money. Catherine replied that she would provide only food for the table.

Catherine now demanded of her son that he arrest and execute his sister’s most recent lover, force her to return and cease her scandalous behaviour. Henry complied but he refused Catherine’s further demand that Marguerite be made to witness the decapitation. An exasperated Catherine instead disinherited her daughter and never spoke to her again.

As it became increasingly apparent that Henry of Navarre would succeed to the throne upon the King’s death so the opposition to it grew and at the forefront of those determined to prevent it was the Duke of Guise. Catherine was reluctant to go to war but saw it as the only option available to prevent Guise, now in command of the Catholic League, from rallying the whole of France against them. She told Henry: “Peace comes with a big stick.”

The war, though brief, was a disaster for the Valois and Henry was forced to concede almost all the Leagues demands.

Sickened by defeat and unable to cope with the vagaries of politics, Henry retired to his private chapel rarely to emerge leaving his mother to tie up the details, sort out the mess, and secure his throne. The fragile peace that Catherine now so painstakingly pieced together was torn asunder when her son feeling safe to do so emerged once again to assert his Royal authority.

He now invited the Duke of Guise to meet with him on 23 December at his palace in Bloise in an act of Christmas reconciliation but after convivial evening of drinking and feasting he had Guise and all his companions murdered.

Catherine, who was sick at the time and had taken to her bed only found out about the event when her son rather sheepishly informed her of it during a visit. Catherine was in despair remarking: “Oh wretched man, what has he done, he is rushing towards his ruin." When she later visited the Duke of Guise’s brother to apologise and offer her condolences, he told her: “Your words, Madam, have led us all to this butchery.” Catherine departed in tears.

Old and tired just four days later on 5 January 1589, aged 69, she died.

The sudden death of the woman who had ruled France for thirty years was little mourned. Indeed, it was said that her passing caused no more commotion than the death of a goat.

She had done her best to do what she considered her duty and preserve the Valois Dynasty for posterity whether this be through artifice, flattery, force or ultimately reconciliation but had been undone by the imbecility of her own children. Her one-time enemy but later friend Henry of Navarre was to say of her:

“I ask you what could a woman, do? Left as she was by the death of her husband with five little children and two families of France seeking to seize the crown – our own and the Guises. Was she not compelled to play strange parts to deceive first one and then the other, in order to guard, as she did, her sons, who successfully reigned through the wise conduct of that shrewd woman. I am surprised that she never did worse.”

King Henry now allied himself with Navarre to oppose the Catholic League, but he was to outlive his mother by only a few months. On 2 August, whilst receiving messages he was stabbed to death by a disgruntled Dominican friar. It marked the end of the Valois Dynasty and the beginning of the Bourbon.

He was succeeded as King by Henry of Navarre who though forced to convert to Catholicism now thought it wise to remain so, better to serve his country.

Henry was considered a just man of resolute good humour and he now made it his policy to enshrine in law toleration for all religions and his Edict of Nantes of 1598, did just that promising freedom of worship, conscience, and civil rights for all. He publicly declared:

“We are all Frenchmen and fellow citizens of the same fatherland; therefore we must be brought to agreement by reason and kindness and not by strictness and cruelty.”

Despite his popularity with the people, Navarre was never afraid to rule with a rod of iron and it is not surprising that he admired the qualities of Catherine de Medici, a woman he had got to know so well and from whom he had learned so much. His rule stood in stark contrast to the effete worthlessness of the Valois Kings who had preceded him.

But there were those who could never reconcile themselves to his religious policies and on 14 May 1610, whilst travelling in his carriage along the Rue de la Ferroniere in Paris he was attacked and stabbed to death by the Catholic fanatic, Francoise Ravaillac.

Many things have been attributed to Catherine de Medici, that she refined French cuisine, introduced the high heeled shoe and brought ballet to France. She certainly entertained lavishly, and her patronage of the arts saw many of the leading sculptors and painters of the day attend the French Court. But she was also accused of involvement in the occult with the presence of Nostradamus among others only adding to the rumour that she dabbled in the dark arts. If so, then it wasn’t as an alchemist or a necromancer but as one of the earliest practitioners of the Machiavellian art of politics.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, Women

Share this post: