Cawnpore: Massacre at the Bibighar

Posted on 19th March 2021

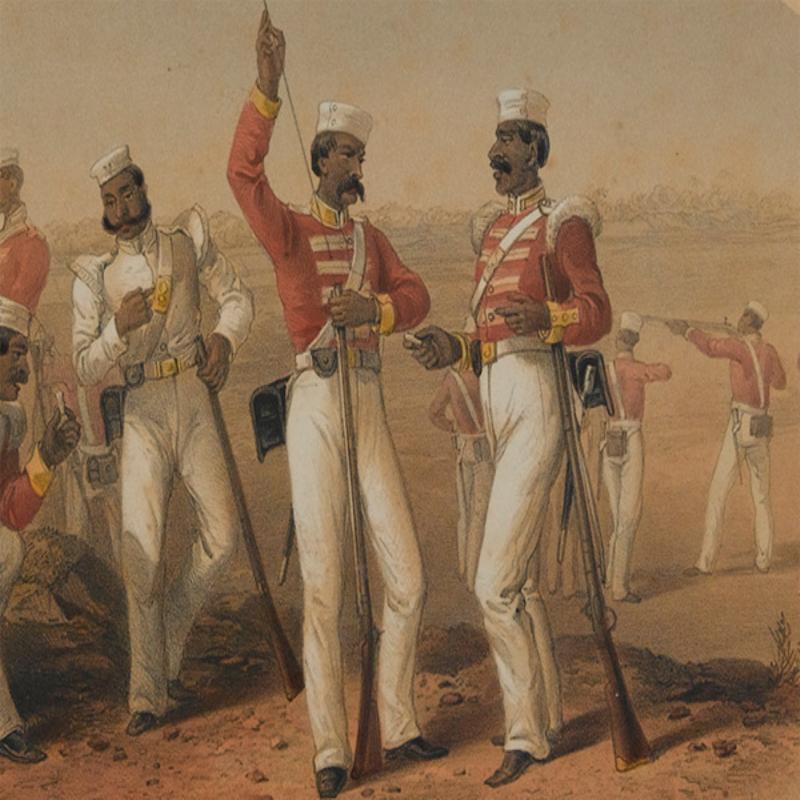

Trouble had been brewing in British India for some time though no one in a position of power seemed to notice. The country was governed by the East India Company through a combination of graft, corruption, and physical force. It co-opted local officials and dignitaries to do its dirty work and backed them up with a private army of 40,000 British and 200,000 Native Indian Sepoys.

Earlier in its history officials of the East India Company had assimilated into local culture and many had taken Indian wives but in recent decades this had changed. Those coming over from England now often saw India to make quick money and little else. They were uninterested in Indian traditions, dismissive of its religions and heedless of the needs of its people. It should have come as no surprise when the powder keg that was British India erupted into open rebellion but through a combination of ignorance and hubris it was to come as a complete surprise to everyone.

The Indian Army which was largely made up of the warrior peoples of the north were often from the higher castes and had once been a well-disciplined and highly respected military force but it had since been degraded by years of neglect and the grievances of the soldiers themselves were manifold. The pay was poor, their quarters often insanitary and promotion almost impossible. Also, the arrogance of many of the British officers and their lack of respect was also a cause of great resentment.

The soldiers of the Indian Army had recently been issued with the new Lee-Enfield rifle. It had been rumoured that the paper covering the cartridges which had to be bitten off before use were greased with beef and pork fat, anathema to both Hindus and Muslims. To touch them would violate the individual who did so.

In fact, the order had already been issued to leave the cartridges ungreased so that the Sepoys could later grease them as they wished but it had not been circulated.

On 24 April 1857 Lieutenant-Colonel George Carmichael-Smyth, a brutal and unsympathetic martinet, ordered the men of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry to form for a fire drill. There had been no expectation that a fire drill was to be called and on a swelteringly hot day the order to parade put the men in a foul mood and they readily believed the rumour circulating that the drill had been called to test the new cartridges. Fearing that they would have to use these cartridges greased with beef and pork fat 85 of the 90 men present on the parade ground refused to obey orders. Carmichael-Smyth red-faced with rage at such wilful disobedience ordered that all the men be placed under arrest.

On 9 May the entire Meerut garrison was assembled to witness their court-martial and they were dealt with drummed out of the service, sentenced to ten years hard labour and deprived of their pensions. Their comrades then had to watch as publicly humiliated they were stripped and shackled. As they were led away to the cells, they noisily berated their fellow Sepoys for not supporting them.

In the early hours of the following morning the remaining Sepoys broke into the prison where their comrades were being held and released them. On breaking open the prison gates they also released hundreds of thieves, bandits and murderers who took their revenge on any white man, woman or child they could find. Christian missionaries were hacked to death, off-duty soldiers attacked in the bazaar and prostitutes slit the throats of their white clients.

The reaction of the Sepoys to the sudden outbreak of violence was mixed some remained loyal while others though no longer willing to obey orders escorted the families of Officers they trusted to safety. But there could be little doubt that many were now in a state of open rebellion.

The British had earlier been warned that an attempt might be made to release the prisoners, but nothing had been done about it. After all, the Indians were always grumbling about something or other and it was a Sunday the day of rest - their complacency would cost them dear.

A few junior Officers who tried to restore order were killed by their own men. The Officers’ Quarters were then attacked, and sixteen women and children killed. A further fifty or so white soldiers and civilians were lso hunted down and murdered. The intensity of the violence shocked everyone.

The British garrison nearby was ordered to stand-to but received no instructions to act until the following day. By the time they moved on to the city of Meerut the rebels had gone.

The news of the rebellion spread like wildfire and before long it had reached Delhi where the rebels demanded that the elderly Mughul Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar become their leader.

Bahadur Shah was an old man who simply wanted to be left alone in quiet splendour to write poetry and translate ancient Persian texts. He was reluctant to get involved but had little choice yet despite the rebel’s insistence he lead them he had no authority and was to be little more than a figurehead. When he tried to protect the white community of the city he was simply ignored, and they were all massacred.

The rebels gathering forces as they went were soon laying siege to the city of Lucknow, but the rebellion was to take a little longer to reach Cawnpore.

The British Commander at Cawnpore was General Sir Hugh Wheeler, who at 67 years of age could have been expected to retire long ago but his experience garnered from 50 years in India made his presence particularly welcome so contrary was it to many who now served within the army and administration. He had taken an Indian wife, spoke several of their languages was popular with his Sepoys. Described as being “a short man, spare of habit, very grey with a quick and intelligent eye, not imposing in appearance except by virtue of a thoroughly military gait,” he was respected and admired in equal measure.

He had heard news of the events at Meerut and Delhi but remained confident that his Sepoys would remain loyal; he was after all not your typical British Officer having adopted many of his adopted country’s customs and traditions. Indeed, so confident was he in the loyalty of his men that he had sent two Companies to help in the defence of Lucknow. His confidence however was to be tragically misplaced and when many of his Indian troops did indeed rebel, he was genuinely shocked and dismayed.

Even so, he had taken some precautions: a small area in the white part of town was fortified though few thought it necessary.

The British community in Cawnpore, along with their Indian servants, numbered around 900 of whom 300 were military personnel and General Wheeler now quickly discovered how poorly displaced his forces were. The fortified area he had created for their protection had only one source of water and it was largely in open ground that provided little cover or shade from the searing heat while the troops found it difficult to dig trenches deep enough in the hard, rocky, ground. With the prospect of a siege General Wheeler now made the difficult decision to dismiss those Indian troops from the compound who had earlier expressed their loyalty.

The rebellion at Cawnpore began on the night of 5 June but there was no all-out assault on the compound. There was a brief exchange of small arms fire and the occasional artillery shell, but it seemed as if no one knew who was shooting at whom and by the morning it appeared that most of the Sepoy Regiments had fled. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief as it appeared that the compound might be spared a prolonged siege, after all.

Soon after sunrise on 6 June Nana Sahib arrived on the scene. He was the adopted son of the Maharatha Peshawa, Baji Rao II and was well-known to General Wheeler with a reputation for being particularly ingratiating and in the past, there had never been enough he could do for his British friends.

Unknown to General Wheeler however, the unctuous Nana Sahib was a bitter man for upon the death of his adopted father he had expected to inherit his title, privileges, wealth and more importantly his generous pension from the East India Company. Indeed, he had even sent a representative to London to petition the Company on his behalf.

Despite lavishing gifts on those he thought men of influence the East India Company found against him on the grounds that he was not Baji Rao’s natural heir. He would not receive the pension and he would not even be permitted to inherit the title. He was furious that he had been denied what he believed was rightfully his and as he was soon to show he was not a forgiving man.

A little after his arrival at Cawnpore he approached General Wheeler in all civility asking if he could be of any assistance. At the same time as he was once again pledging his loyalty to the British, he was rallying the departing rebels and returning them to the city. He had effectively taken charge.

The subsequent rebel attacks on the British entrenchments were half-hearted and easily repulsed; but then it wasn’t necessary to take the compound by storm as its openness made it easy prey to sniper and artillery fire both of which soon began to take their toll. Disease had also broken out within the compound and medicines, along with food and water were all in short supply while it remained relentlessly and insufferably hot.

A week into the siege, General Wheeler’s son Lieutenant-Colonel Godfrey Wheeler was decapitated by an artillery shell. The loss of his son seemed to break the spirit of the old General and when Nana Sahib approached him with an offer of safe conduct for all those within the compound, Wheeler was at first inclined to accept but then his resolve would stiffen, and he would refuse any surrender terms. There was also considerable disagreement among his Officers as to whether or not Nana Sahib could be trusted, and many wanted to continue the siege. General Wheeler told them he had long been acquainted with Nana Sahib’s and knew him to be a friend of the British. Finally, he overruled them and made the decision to surrender. He would place his trust in Nana Sahib., he said.

Nana Sahib had lain on carts for the transportation of the women and children and permitted the soldiers to retain their firearms but as they marched out of the compound on the morning of 27 June it was an ominous sign that the entire rebel army was present to escort them.

They arrived at their departure point at Satichaura Ghat around eight o’clock in the morning and were relieved to see that boats had been provided for their use. It did not go unnoticed however that many of them were far from the shore perched on sandbanks while others seemed to be in a state of some disrepair.

Tatya Tope, Nana Sahib’s Military Commander now arrived to take personal charge of the escort. The atmosphere was tense, and a strange silence descended upon the scene until it was broken by the sound of firing. No one knows for certain who fired the first shot or whether the attack had been prearranged though it seems likely that it was, and that Tatya Tope was responsible.

The British who had by this time scrambled aboard the boats now came under artillery fire. Some of the boats were holed beneath the waterline and began to sink while others were simply blown apart and as the bedraggled survivors waded ashore, they were cut down by the waiting Indian Cavalry.

General Wheeler’s boat which had been the first to leave struggled to make it to safety but kept becoming stranded on the sandbanks; some of the British soldiers among the sixty or so on board made sorties against the rebels to try and buy the others time. Four of them who had become stranded from the boat would later escape making them the only male survivors of the massacre.

General Wheeler’s boat managed to stay afloat through the night but in the morning and with the coming of daylight he was forced to surrender. All those aboard including General Wheeler were executed on the orders of Tatya Tope along with any other men taken prisoner.

The 120 women and children taken captive were returned to Cawnpore where they were incarcerated in the Bibighar, or The House of the Ladies. There they joined those Indian women who had remained loyal to their British masters.

The women were placed in the care of a prostitute, Hussaini Khanum, a brutal and unsympathetic woman who took pleasure in humiliating her charges sometimes slapping them or forcing them to strip and putting them to menial tasks.

Nana Sahib, wanted to use the women as bargaining chips for his own safety. He was aware that an army had been dispatched to the relief of Lucknow under the command of General Henry Havelock and that the troops he had sent to oppose him had been defeated.

General Havelock was determined to punish those who put innocent women and children to the sword and the Indians he encountered were dealt with harshly. His path to Lucknow was marked by burning villages and littered with corpses. He was clearly not a man to be negotiated with and a frightened Nana Sahib knew the women he had in his custody could not be ransomed and if rescued could tell of the massacre and of his part in it.

Along with Tatya Tope he now made the decision to kill the prisoners, but those Sepoys assigned the task refused to carry it out. They were soldiers and would not murder women and children. Tatya Tope threatened to execute those who refused but they remained unmoved. Hussaini Khanum now berated them as cowards. Some of the Sepoys agreed to fetch the women and children from the Bibighar but they refused to leave tying the door handles so they could not be opened and barricading themselves in.

In frustration the Sepoys fired through the windows of the Bibighar but hearing the screams and seeing the women huddled together for their own protection they soon stopped. When ordered to do so again they fired their rifles into the air.

Hussaini Khanum, despairing at the soldier’s lack of manliness took it upon herself to hire some local butchers to do the job. They did not share the Sepoys scruples and soon battered down the doors and went about their jobs with relish dragging the women and children out of the house and slaughtering them with meat cleavers.

Nana Sahib had earlier excused himself so that he did not have to witness the scene. The following morning the bodies were gathered up and many of them disposed of down a nearby dry-well.

Not all the women had been killed in the initial massacre and had feigned death in an attempt to hide some of the children. When the Indians came to collect the remaining bodies the following morning, they told the children to run for their lives and six managed to escape but they were later hunted down and decapitated. The women were simply thrown into the well, still alive.

British troops under the command of General Napier arrived at Cawnpore on 16 July and quickly recaptured the city.

They had expected to find the imprisoned women and children still alive but instead they found the Bibighar a slaughterhouse soaked in blood with brain spattered walls, severed limbs, discarded clothing and great tufts of female hair. When they later discovered the bodies of the victims thrown unceremoniously into the well the outraged British troops went on the rampage looting homes and massacring civilians - there was no attempt to stop them.

The Massacre at Cawnpore, particularly that at the Bibighar, was to have a profound effect on the British response to the Mutiny. It appeared to confirm many in their view of Indians as little more than savages and those rebels who fell into British hands were shown no mercy.

Many of the captives were forced to strip naked and smear beef and pork fat onto their bodies and though most were hanged some were tied to cannons and quite literally blown apart. Those Sepoys who were taken prisoner at Cawnpore were made to lick the blood from the walls of the Bibighar before being executed.

There were those among the British troops who complained at the treatment of the prisoners, but they were always a minority and whenever they did so they would be drowned out by the cries of – Remember Cawnpore!

Tatya Tope was to go onto lead a guerrilla campaign against British forces that was to earn him the grudging respect of his foes before he was finally captured by the troops of General Napier and hanged on 18 April 1859.

Nana Sahib, who had made good his escape from Cawnpore briefly remerged to assist in the campaign of the Rani of Jhansi but once the defeat of the rebels became inevitable, he disappeared never to be seen or heard of again.

Share this post: