Charge of the Light Brigade: Somebody Blundered

Posted on 19th May 2021

For its courage and sheer bloody mindedness alone, the Charge of the Light Brigade has sealed for itself a special place in the annals of military history but it still remains a single engagement in a much broader conflict.

The Crimea War was to have its origins in a row over who was responsible for the protection of Christian sites in the Ottoman controlled Holy Land. France had long seen itself as this protector, but Russia disputed this and now threatened the Turks with military action if they did not acquiesce to their demands for greater influence in the affairs of their Empire.

The once mighty Ottoman Empire which had by the 1850’s become the "Sick Man of Europe’, economically backward, administratively inept and militarily weak had little choice but to comply.

The recently crowned French Emperor Louis Napoleon seeking to assert himself on the world stage responded by sending a warship to the Black Sea looking to likewise intimidate the Turks. It worked, and they now agreed that the Roman Catholic Church would be the supreme Christian Authority in the Holy Land and should be presented with the keys to the Church of the Nativity previously in the hands of the Greek Orthodox Church.

Russia which had for a long time greedily eyed those parts of the Balkans still under Ottoman control now used their defence of the Orthodox Church as an excuse to wage war and so in July 1853 they invaded the Danubian provinces of Moldova and Wallachia with the aim of forcing them to cede territory by force of arms.

Russian expansion at the expense of its weak Turkish neighbour had long been a concern of the other Great Powers of Europe and both Britain and France now rallied to the Ottoman’s, but they stopped short of war. The Turks now tried to force the hand of their new allies by formally declaring war on Russia themselves.

In late November, 1853 the Russians destroyed the Turkish Fleet at the Battle of Sinope and tensions mounted as it seemed Constantinople might fall and the Russian Black Sea Fleet would gain access to the Mediterranean.

An ultimatum was now presented to the Russians to withdraw its forces from Moldova and Wallachia immediately and enter peace negotiations or face military intervention. By late March 1854 when no response had been received, war was declared.

The Allies did not land at the ominously named Calamita Bay on the Crimean Peninsula until September. Much to their surprise given the long delay between the declaration of war and the beginning of operations on the Russian hinterland the landing went unopposed, and the Allies were able to establish a camp at Balaclava which quickly became their main port of supply.

The landing at Calimita Bay was followed a week later by a surprise, Allied victory at the Battle of Alma which cleared a large Russian Army from the heights above Sebastopol leaving them able to lay siege to the city the capture of which was their primary aim.

Prince Menshikov, the Russian Military Commander, who had declined to fully engage the Allies since the shock defeat at Alma, now gathered his forces for an all-out assault on the port of Balaclava itself. If he could capture the Allies only access to supplies, then they would be stranded and would have to either abandon the peninsula or starve.

The attack began in the early morning of 25 October and the initially outnumbered Allies were taken completely by surprise as the Russian infantry swept down from the hills and captured a series of Redoubts (large, fortified pits defended by artillery) due in large part to the poor performance of the Turkish troops manning them. With the Redoubts abandoned the Russian Cavalry were able to advance unopposed.

Chaos reigned in the Allied camp as no one seemed to know what was happening or what to do. The attack was only stalled by the quick thinking of General Sir Colin Campbell who led the troops of the 93rd Highland Brigade into the fray and held up the Russian attack at bayonet point in what became famous as "Thin Red Line."

The Highlanders had provided the Allied Commanders with enough time to organise. The Russian Cavalry were now counter-attacked by General Scarlett's Heavy Brigade. They were eventually pushed back following a ferocious struggle that surprisingly resulted in few fatalities due to overnight rain having sodden uniforms and blunted swords, but a catastrophic defeat had been avoided.

However, much to their frustration the bulk of the British Cavalry under the command of Lord Lucan had been left to watch events from the side-lines. They could see that the Russians were in disarray and there was an opportunity to act decisively and possibly end the war there and then. But the order to attack never came.

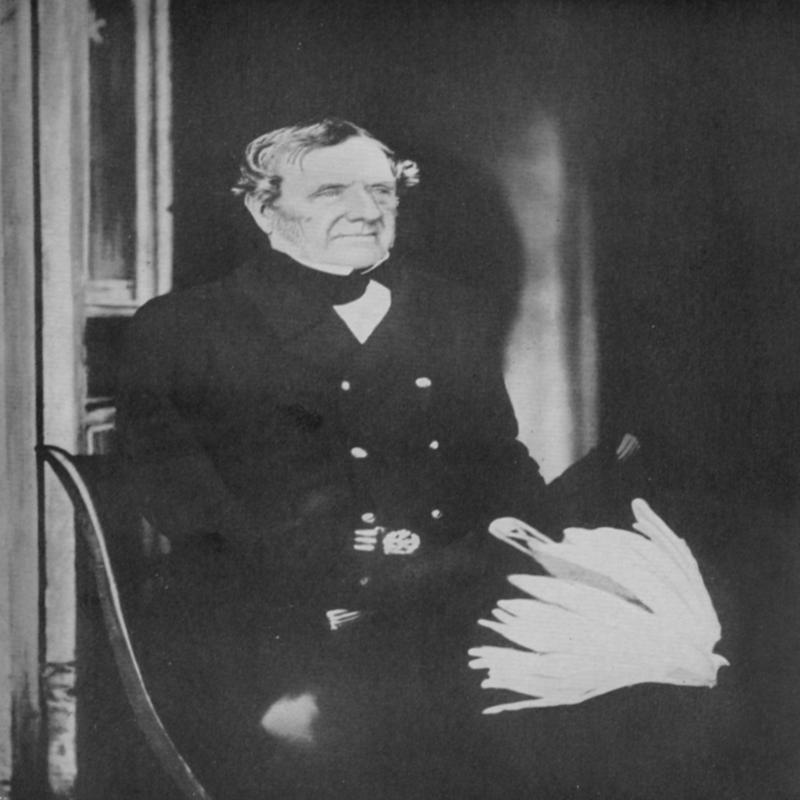

Lord Raglan, Commander of the Allied forces in the Crimea had displayed a disinclination to commit his cavalry ever since the beginning of the campaign remembering all too well it was said the decimation of the Scots Greys at Waterloo forty years earlier. He had been a close associate of the Duke of Wellington and ever since his death had been the pre-eminent Officer in the British Army, few had been opposed to his appointment as Commander-in-Chief. But he was sixty-six years old and had not seen action since he had lost his right-arm at the same aforesaid Waterloo in 1815.

He was known to be indecisive, rambling in his speech and vague with his orders. He often didn't seem to grasp what was going on and rather embarrassingly kept referring to the French as the enemy and to the increasing frustration of his subordinates he yet again seemed to be allowing a battle to peter out into a stalemate. Some rather sarcastically suggested that he might be enjoying his regular afternoon nap.

Reports soon began to reach the Allied Command that the Russians were removing the guns from the abandoned Redoubts. Not only would their removal be militarily damaging but to lose one’s guns to the enemy was considered shameful. Such a thing could not be tolerated, and something had to be done and quickly.

Lord Raglan leisurely surveying the battlefield through his telescope hastily scribbled a note and handed it to his Aide-de-Camp Colonel Airey. The note was for the attention of Lord Lucan, and it read: "Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance rapidly to the front, and try to prevent the enemy from carrying away the guns. Troop of Horse Artillery may accompany. French Cavalry is on your left. Immediate."

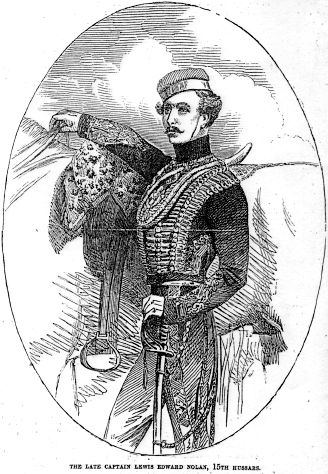

Airey now looked around for someone he could rely upon to deliver the note safely. A young Officer of Irish descent Captain Lewis Nolan now volunteered.

Lewis Nolan was a brash, excitable and often insubordinate young man who had written a book about how cavalry should be used in warfare and was desperate to see his theories put into practice. He was a brilliant horseman himself but was also arrogant and opinionated. He was delighted to be given the opportunity to play a role in such momentous events and rode with haste as if the future of the Empire depended upon it the words of Lord Raglan ringing in his ears – tell his Lordship to attack immediately.

Nolan delivered Raglan's note with great urgency thrusting it into Lucan's hands who seemed confused by the order. From his position low in the valley, he could not see any guns. He asked, Nolan: "What guns, where? Attack, sir! Attack what? What guns, sir?" An exasperated Nolan desperate to see action thrust out his arm and pointed towards the Russians at the other end of the valley and shouted, "There is your enemy! There are your guns!”

Lucan appeared uncertain whether to trust Nolan, but he could see no other guns and he had his orders. He rode over to his brother-in-law Lord Cardigan, the Commander of the Light Brigade who seemed as confused by the meaning of the orders as Lucan had been. Turning to Lucan he said: "Allow me to point out to you that there is a battery in front and on each flank." His remarks were greeted with silence.

James Thomas Brudenell, the 7th Earl of Cardigan, was no doubt brave but he was also an arrogant, rakish, insensitive, stubborn and often very stupid man. His life had been mired in scandal and controversy and he was notorious for a series of sexual and drunken escapades going back many years. Often brought to book for his behaviour his response would be to challenge those who criticised him to a duel and as a result he was often in the newspapers. .

Like most British Officers Cardigan had purchased his Commission as Commander of the 11th Hussars, or the Light Brigade, and had kitted them out at his own considerable expense and as such treated the Regiment as his own personal fiefdom issuing arbitrary and often brutal punishments to those who stepped out of line. He was deeply unpopular with both his Officers and men and seems to have been heartily disliked by almost everyone who ever met him. Despite all this however he had trained his men relentlessly and they were considered the best and the most dashing Regiment of Cavalry in the British Army, if not in the whole of Europe, and all those concerned revelled in their reputation.

During his time in the Crimea, he declined to camp with his men but remained on his private yacht moored in the bay where he partied late into the night enjoying the best champagne and it was said the pleasure of a number of his Officer’s wives. Indeed, his debauched life had taken its toll and he looked older than his fifty seven years and an Officer who saw him at the time remarked: “Lord Cardigan arrived today, he looks very old. I do believe we need younger men.”

Lord Lucan and Lord Cardigan may have brothers-in-law, but they had not been on speaking terms for many years and would often avoid the same functions merely to avoid having to look upon one another, and on the rare occasion they did speak it would invariably result in a furious row. The appointment of Cardigan as Lucan’s subordinate had been an error of judgement by Lord Raglan, and everyone knew it.

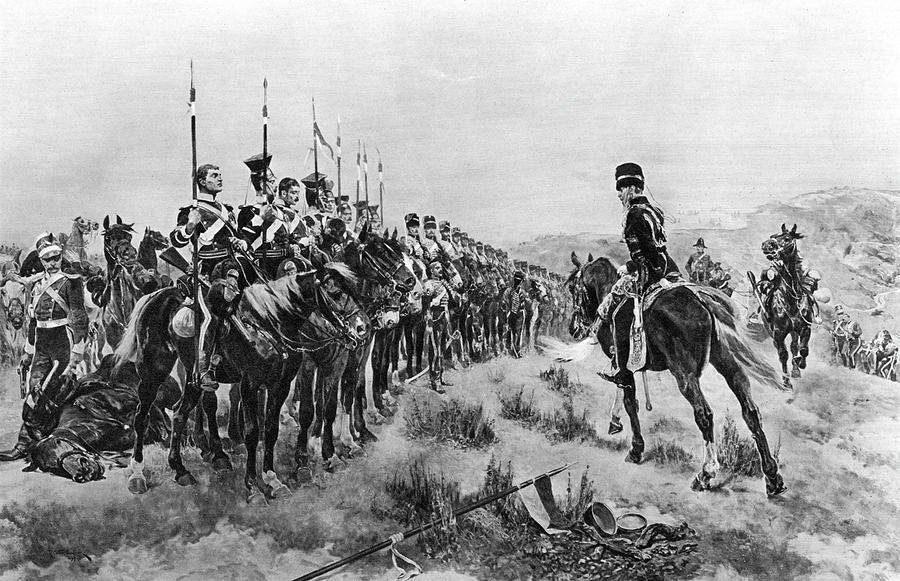

Lord Cardigan, having made it clear to his superior that cavalry assaulting artillery without infantry support flew in the face of all military precedent and after exchanging the usual insults assembled his Brigade, prepared them for battle and set off down the valley at a slow orderly trot.

As they advanced however it soon became apparent to those watching that they were going the wrong way. The orders had been misinterpreted by someone for weren't they supposed to be advancing up the valley towards the Causeway Heights to retrieve the guns taken by the Russians not advancing down the valley to attack the Russian guns themselves.

Lewis Nolan, who had enthusiastically taken up his position in the front-line also realised this. He raced ahead of the Brigade shouting at the top of his voice that they had gone the wrong way and must turn back. Lord Cardigan appalled that any Officer should have the temerity to ride in advance of his General deigned to ignore him. At that moment a shell exploded above Nolan's head riddling his body with shrapnel and killing him instantly. He was the first casualty of the Charge of the Light Brigade.

Lord Lucan, who could also see what was happening and knew full well what would result, was not going to come to the assistance of his hated brother-in-law and held his Heavy Brigade back. Lord Cardigan and his Cherry Bums as he liked to call them were on their own.

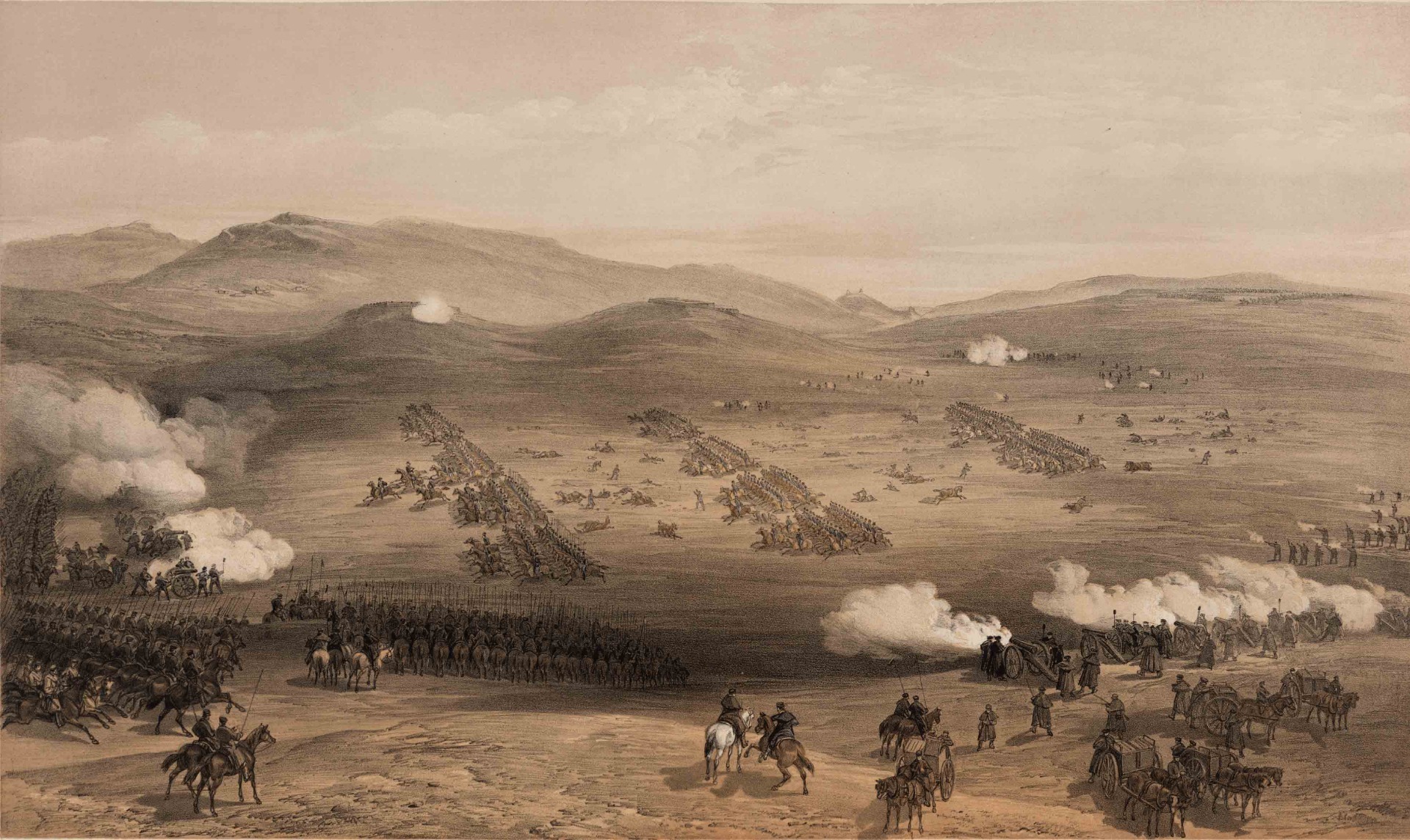

With cannons in front and on either flank the Light Brigade continued their advance. Shells were bursting among them, and swathes were being cut in their lines. Snipers were taking pot-shots from the hills and casualties were mounting but Lord Cardigan maintained a steady trot and it wasn't until he was only 200 yards from the Russian guns that he ordered the charge.

Those troopers of the Light Brigade still remaining lowered their lances and yelling at the top of their voices spurred their horses to charge into the Russian guns at full pelt. After a short furious fight, the guns were taken but it was to be a short-lived success. Russian cavalry stationed behind the guns now counter attacked. The ensuing fight was desperate and deadly. A Russian, Lieutenant Koribut Kubitovich wrote: "The English fought with outstanding bravery, and when we approached their dismounted and wounded men, even these refused to surrender and continued to fight until the ground was soaked in their blood."

With nowhere else to go and no hope of support the survivors of the charge had little choice but to simply return from whence they had come. Lord Cardigan who had been the first to arrive at the Russian guns had simply turned his horse around and rode back alone, again at a steady trot. He was completely unscathed and upon his return said to the first Officer he met, "I appear to have lost my Brigade."

In the meantime, his men had to run the gauntlet once more as pursued by the Russian cavalry and under heavy fire they were only saved from complete annihilation by the timely arrival of French Curassiers who cleared the Russian cavalry from the field.

From an original complement of 650 or thereabouts only 195 returned up the valley, many on foot. Official figures at the time put the number of dead at 121 but it has since been estimated that as many as 247 were killed with many more wounded and captured.

The charge had lasted less than 20 minutes, and fighting had ceased elsewhere as people took time to watch the spectacle from afar. What they had witnessed was the destruction of the Light Brigade. The French General Bousquet was heard to say, "C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas le guerre," (It is magnificent, but it's not war).

Upon his safe return Cardigan informed Lord Lucan that he had carried out his orders as instructed and wished to know of the whereabouts of that damnable Nolan who had dared to ride before him during the charge only to be informed that he had just ridden past his dead body. He then asked if anyone had seen his Regiment.

The recriminations for the terrible blunder started almost immediately. Lord Lucan was the first to be blamed for not coming to the support of his brother-in-law. It was suggested that his tardiness was the result of their mutual loathing for one another. He demanded a court-martial to clear his name. This was denied but he was cleared of any responsibility in a later Inquiry. He was particularly upset that aspersions had been cast upon his courage when he had always been a soldier’s soldier, dining with his men and sharing their hardships; so unlike his brother-in-law who had spent his time in the Crimea frolicking with various women upon his private yacht, and he had also certainly saved the Heavy Brigade from a similar fate by refusing to commit them to battle.

Lord Raglan only avoided criticism by dying in 1855, though he was to be largely blamed for the fiasco following his death.

At first the response to the gallant Charge of the Light Brigade was only positive despite the implied criticism of military incompetence that resonated in William Howard Russell’s dispatches to The Times newspaper which, were followed not long after by Alfred Lord Tennyson’s epic poem.

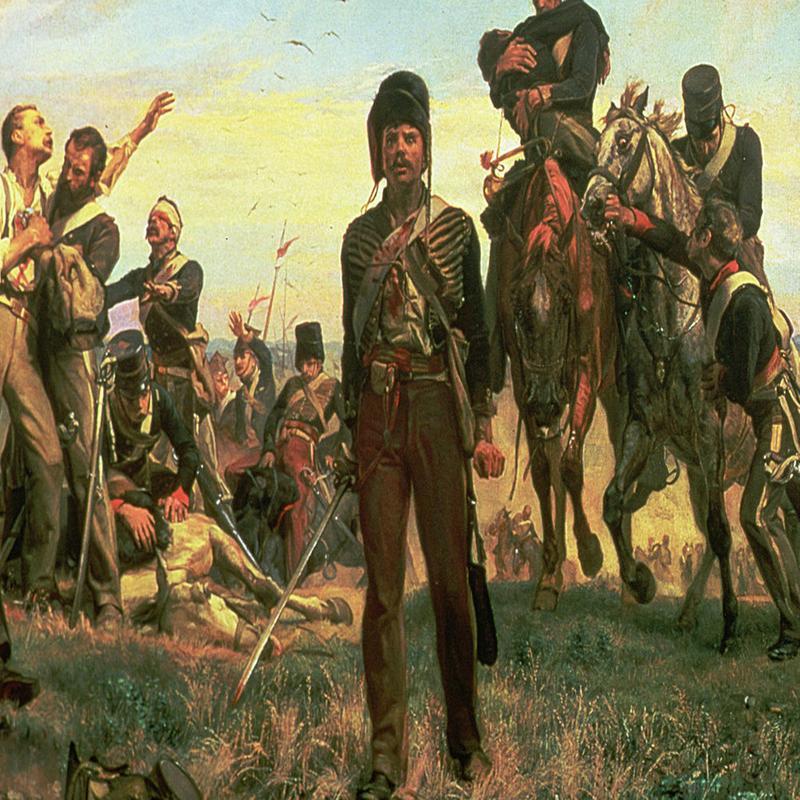

As a result, Lord Cardigan returned to England a national hero and he was applauded and cheered wherever he went. When a painting was commissioned of the charge, he had insisted that it be changed to show him riding well out in front of his men and so it was. There was very little England wouldn’t do for its new national hero.

He enjoyed nothing more than telling stories of his role in the charge and demanded that mention be made of it at any public meeting or function he attended.

As the conflict in the Crimea dragged on for a further two years and the appalling litany of death not in battle but from sickness and neglect mounted public opinion turned against the war and the fiasco that was the Charge of the Light Brigade came to be seen as the prime example of the aristocratic arrogance, amateurism and incompetence that had seen so much pain and death inflicted on so many for so very little gain.

None of this impacted upon Lord Cardigan who was insensitive to criticism whether implied or otherwise. He dined out on his heroic status for the rest of his life. He was to die in 1868, aged 71 after falling from his horse, drunk some said.

Share this post: