Charles II's Great Escape

Posted on 16th March 2023

On 1 January 1651, the twenty-two-year-old Charles Stuart, eldest son of the executed King Charles I and heir to the English Throne was crowned King of Scotland at Scone. The previously exiled Charles had in fact been declared King by the Scots in February 1649, just a week after his father’s death but it had taken two years of painful negotiation to make it a reality.

Much to his irritation he’d had to sign the Solemn League and Covenant which authorised Presbyterian Church governance throughout the Island of Britain. This was the same Covenant that his father had refused to sign and as a result the Scot’s had allied with the forces of Parliament thereby guaranteeing his defeat in the Civil War.

Charles hated the Covenanters but if he was to retrieve his Crown and avenge his father he needed the support of the Scots.

In August 1651, Oliver Cromwell, the de-facto ruler of England though not yet Lord Protector was campaigning in the north of Scotland. Charles was eager to seize the opportunity provided by Cromwell’s absence and so contrary to the advice of the experienced Sir David Leslie in command of the Scottish Covenanter Army he decided to make a dash for London hoping that as his army advanced south English Royalists would rally to his cause.

The prospects of success may have appeared good to the impetuous young Charles, but the invasion came as no surprise to Cromwell who had already made provision for just such a move. Three separate armies had been formed to meet the threat under the experienced Civil War Commanders Thomas Harrison, Charles Fleetwood, and Thomas Fairfax. Upon hearing news of the invasion Cromwell, leaving Sir George Monck in command of the army in Scotland, made haste for England.

Ordering the cavalry of John Lambert to harry the Covenanter Army, Cromwell had also taken the precaution of having the most prominent known Monarchists either arrested or put under close surveillance while most common people rather than rally to the Royalist cause viewed the Scottish Army as the invading force it undoubtedly was and stayed at home. At the same time Cromwell was happy to allow the Scots to penetrate deep into England and far away from their home base.

Finally, on 3 September, with his army exhausted and short of supplies, Charles was forced to take refuge in the town of Worcester. In no time he was surrounded and with his army of 15,000 men hemmed in by forces twice the size of his own the ensuing battle was a foregone conclusion even though for a time the Scots fought well. That was until Cromwell arrived and provided the impetus for final victory.

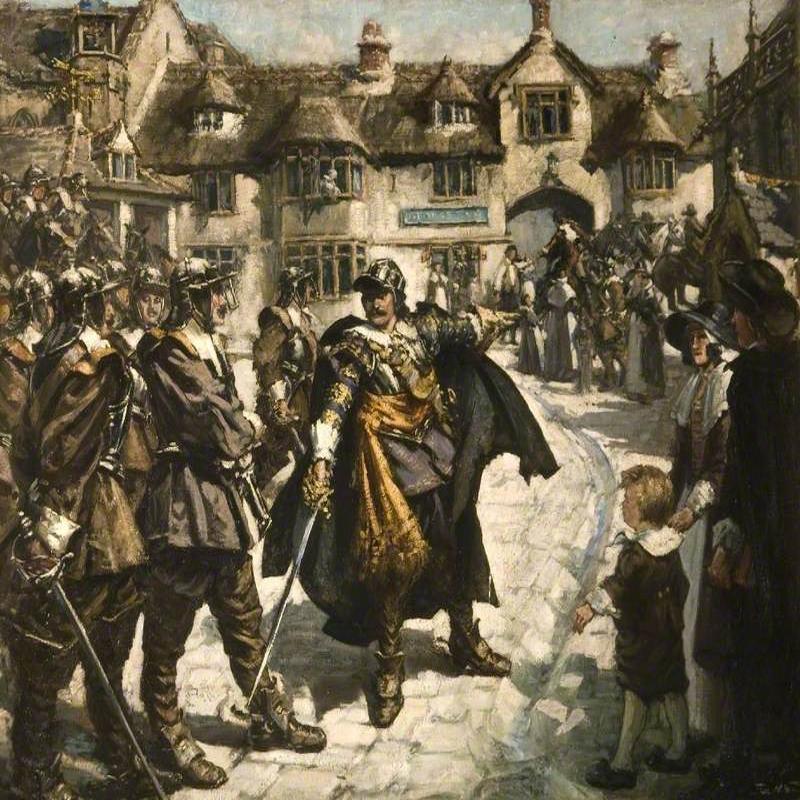

As the light began to fade with Parliamentary troops in the streets of the town and the fighting hand-to-hand the Earl of Cleveland led a last desperate charge down Worcester High Street to provide the opportunity for Charles and a few others to make their escape through the unguarded St Martin’s Gate.

The Battle of Worcester had cost the Scots 3,000 dead and 10,000 prisoners to Parliament’s much lighter casualties of 300 killed and 600 wounded. It also left Charles Stuart King of Scotland and heir to the English Throne a fugitive in his own country and a hunted man.

Parliament immediately offered a reward of £1,000 for the capture of the rogue Charles Stuart. He knew that if he was caught, he would suffer the same fate as his father. He also knew that anyone caught helping him would likewise be executed.

Charles had fled Worcester accompanied by Lord Derby, Lord Wilmott and a small number of others. They decided to head for Shropshire, a County that was known to contain many Royalists and had remained loyal to his father. Stopping off at an Inn it was decided that the group should split up with Charles travelling alone except for Lord Wilmott and one attendant. It was a wise decision for the other larger party was soon after intercepted and captured.

On 4 September, Charles and Lord Wilmott arrived at Boscobel House, the Estate of Charles Gifford who had been with Charles at Worcester. In the absence of its master the Estate had been run by the five Catholic Penderell brothers who were eager to help. The first thing they had to do was disguise Charles which was easier said than done.

At 6’2″ at a time when the average height of a man was barely 5’8″and with long dark hair set in ringlets, a pinched face and swarthy complexion he was an easily recognisable figure. Still, they did their best and provided with a common man’s clothing he had his hair cut and was advised to stoop.

Charles remained in the Priory of the house until he and Richard Penderell decided that it would be more advisable to hide in the woods. A little later a company of troops arrived at the Estate and ransacked the Priory before searching the grounds. Charles later said:

“In this wood I stayed all day and all night without meat or drink, and by very great fortune it rained all the time which I think hindered them.”

On 5 September, Charles tried to make it into Wales but found the crossing over the River Severn too closely guarded. Returning to Boscobel they found the Estate still crawling with Parliamentary soldiers and Charles was forced to hide in a nearby Oak Tree, the famous Boscobel or Royal Oak. Later that night he returned to the house and hid in one of its many priest holes.

On the evening of 7 September, taking the advice of Lord Wilmott, Charles left Boscobel for Mosely Old Hall and in the darkness his horse stumbled throwing him to the ground and Humphrey Penderell who was with him joked, “It is not to be wondered at that it stumbled it has the weight of three Kingdoms on its shoulders.”

While at Mosely Old Hall he was visited by Father John Huddleston who provided him with some much-needed spiritual comfort. That night Charles slept in a bed for the first time since his flight from Worcester. Early next morning he was woken by a noisy fracas. When he looked out of his window, he could see it was a party of his Scottish soldiers in running through the grounds. They had good reason to flee for it had just been announced that 8,000 of their captured comrades were to be transported to the Americas as indentured slaves.

Parliamentary soldiers arrived not long after and Charles only just managed to hide in time. It was no longer safe to remain at Mosely Old Hall and on 10 September he travelled onto Bentley Hall.

John Lane, who owned Bentley Hall, had been a Royalist Officer and had remained loyal to the Stuart cause and his sister, Jane Lane, had recently received a permit to travel to Somerset to visit a friend who was soon to have a baby. It was decided that Charles should accompany her in the guise of her servant William Jackson. He was provided with a servant’s attire and his face was covered in butternut to make it appear more weather-beaten.

As a servant Charles was made to walk most of the way but he did occasionally get to ride with Jane on her horse, something he no doubt enjoyed. Travelling with them were Jane’s sister Withy Petrie, her husband John, and a Royalist Officer Henry Lascelles.

Lord Wilmott, who was also present refused a disguise saying that he was no common man and would not dress as such, or affect the mannerisms and language of such. Therefore, it was decided that he should ride a mile ahead of the party and act as a decoy. If he was stopped, he was to say that he was out hunting.

During the journey Jane’s horse lost a shoe and as her servant Charles was obliged to go to a blacksmith to get it re-shod. Feigning a common accent Charles engaged the blacksmith in conversation. He later related the story to the diarist Samuel Pepys:

“As I was holding my horse’s foot I asked the smith what news? He told me that there was no news he was aware of, since the beating of those rogues the Scots. I asked if there was none of the English taken who had joined with the Scots. He answered that he did not know if that rogue Charles Stuart were taken but some of the others were, he said. I told him that if that rogue Charles Stuart were taken he should be hanged. I talked as an honest person does, and we parted.”

Charles was to acquire a taste for this sort of banter even discussing what should be done with the rogue Charles Stuart with Parliamentary soldiers in local taverns. While such daring may have amused the future King of England it did nothing for the already shredded nerves of his companions.

Charles and his party were heading for Bristol in the hope of finding a ship to take them to France. On the way they stayed over at the home of the Norton family who were old friends of Jane’s. They did not however share either her politics or her loyalties so Charles’s true identity was kept secret from them but they became suspicious of this servant who was so tall, spoke so little, and appeared so grand.

Charles recognised one of the Norton’s servants to have been a member of his personal bodyguard at Worcester and so to allay any suspicions he boldly asked the servant to describe the King’s appearance. The servant paused for a moment before replying, “He is at least three fingers taller than you.”

Unable to take ship from Bristol, Charles and his party now headed south.

On 16 September, Charles and Lady Jane travelled to Castle Cary before moving onto Trent House the home of Colonel Francis Wyndham, another Royalist Officer. It was while at Trent House that he witnessed the bizarre spectacle of the local villagers celebrating the reported capture and execution of Charles Stuart. He was eager to join in but was instead persuaded to lie low. In the meantime, Wilmott and Wyndham had been to the ports of Weymouth and Lyme Regis to try and negotiate a passage to the Continent.

On 22 September, Charles narrowly escaped capture when travelling with Jane’s young niece they encountered a company of Parliamentary troops. Questioned as to their identity they posed as a runaway couple and were released but the troops had obviously been tipped off for they soon returned and as they began to close in Jane’s niece, very scared, began to cry. Charles managed to calm his young companion down and they managed to evade capture by moving from hedgerow to hedgerow, sometimes when the troops were almost upon them.

Despite this lucky escape it was becoming increasingly evident that the refugee King would not remain at liberty for much longer.

The following night Charles and his party stayed at the George Inn. Late in the evening the local Constable with forty troopers arrived with orders to search the premises. It had been reported that the Rogue Charles Stuart was hiding nearby. As luck would have it in all the excitement a pregnant young woman went into labour. In the ensuing confusion Charles and his companions made good their escape but the noose was becoming ever tighter. I t was also clear that someone was betraying them.

Finally, on 7 October a deal was struck with Captain Nicholas Tattersall of the Surprise sailing out of Shoreham to take certain anonymous people to France for a fee of £80.

Charles immediately set out for Shoreham where he again stayed at a tavern called the George Inn. Here he met Captain Tattersall and it was during their discussion that the Innkeeper recognising the heir to the throne fell to his knees in supplication. This act spontaneous of deference did not in any way diminish his business sense however and upon realising who his anonymous passenger was he immediately demanded a fee of £200. The money was only found with great difficulty and even then, the plan was almost scuppered when Tattersall’s wife realising what he intended to do and fearing for his life, locked him in his room.

At last on 15 October, Charles, Lord Wilmott, and a number of others set sail for France. As expected, the incident at the Inn had been reported and just two hours after they had departed for France a company of troopers arrived to arrest them.

Nine years later, on 29 May 1660, the day of his thirtieth birthday, Charles Stuart crossed from the Netherlands on another ship once the Naseby now renamed the Royal Charles in his honour and returned to London as King of England. In the end he had received the Crown from a Parliament that had once hunted him like a wild beast.

The languid and always affable King Charles II never forgot the people who had put their own lives at risk to save his, and they were all amply rewarded. He had also acquired during his time on the run a healthy respect for the courage and dignity of the common man.

Tagged as: Monarchy, Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: