Christopher Marlowe: Poet, Playwright, Heretic, Spy

Posted on 19th March 2021

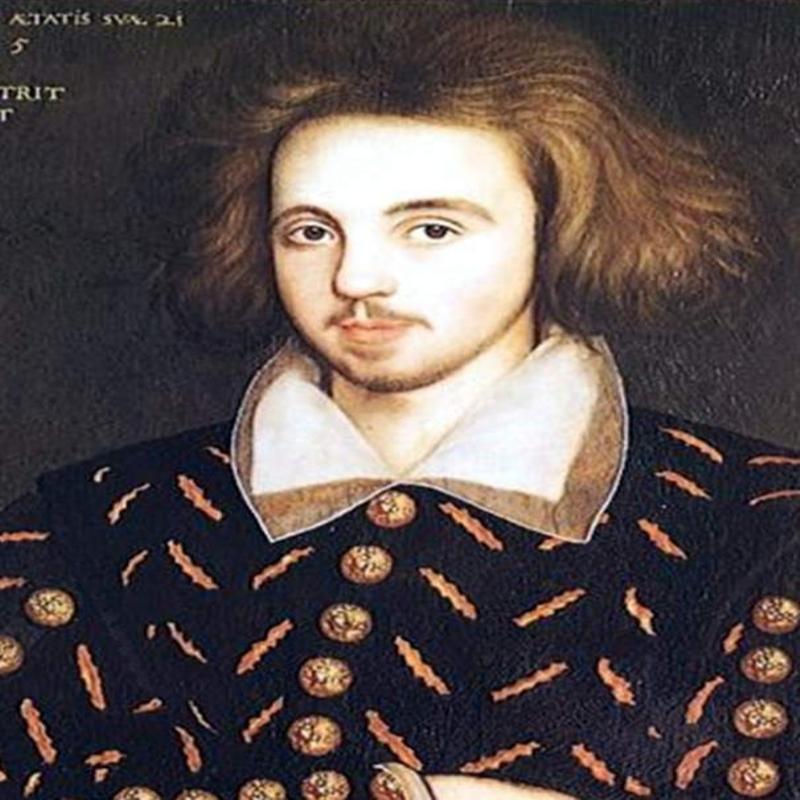

Christopher Marlowe was a great Elizabethan playwright whose short life was clouded in controversy and shrouded in mystery. In a prolific career that spanned a mere six years he was the most brilliant and imaginative writer of his time, and his plays were even more popular than those of his contemporary, William Shakespeare.

Yet he was cut down in his prime, the victim of either murder or pre-determined assassination and thus remains one of the great enigmas of English literary history.

Christopher Marlowe’s exact date of birth is unknown, but he was baptised in Canterbury, Kent, on 26 February 1564, just two weeks before Shakespeare himself was similarly baptised in Stratford-Upon-Avon.

Though he was only the son of a low-born cobbler his father managed to scrape together the money to send his son to the local School where he so impressed academically that he obtained a scholarship to attend Corpus Christi College in Cambridge.

From the outset of his academic career his life was the subject of rumour absent as he was from his studies for extended periods of time, far longer than those permitted by the College, and which normally would have led to his expulsion but no action was ever taken against him. He also lived extravagantly and well beyond his means, but few people questioned where he got his money.

Despite his frequent absences and poor record of study he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in 1584, but three years later the University refused to grant him his Master’s Degree following rumours that he had secretly converted to Roman Catholicism and it took an intervention by the Privy Council in London who informed the College Authorities of his “faith and good service to the Queen,” to make them relent.

There seemed little doubt that Marlowe was working as an agent for Sir Francis Walsingham’s Intelligencer Service and that the story of his conversion to Roman Catholicism had almost certainly been circulated to help him infiltrate dissident circles abroad for the very idea that the notoriously blasphemous Marlowe who was known to refer to Christ as a bastard, the Virgin Mary as a whore and advised people not to believe in Biblical hobgoblins had undergone a religious conversion struck those who knew him as absurd.

Marlowe was not a man who at first glance would appear the perfect material for a spy. He was loud, garish, quick-tempered, and always up for a fight either verbal or otherwise with the one often leading to the other. He lived life to the full, he was a heavy drinker who frequented the local taverns well into the night and an enthusiastic participant in the recent fad of smoking. When he wasn’t distracted by his writing or on Government business, he spent his time chasing young men telling anyone willing to listen: “He who loves not tobacco and boys is a fool.”

He also loved to write, it was something that came naturally to him, and the intensity of his writing reflected the intensity of his life. His first play staged in London was “Tamburlaine the Great” and it was a huge success. It was followed by a sequel, Tamburlaine Part Two.

Marlowe had discovered that writing was not just satisfying in its own right but also a means by which to make money. For him it was never art for art’s sake, having had a commercial success he was desperate to follow it up with another. Even so, he could never be accused of merely writing for the satisfaction of his audience tackling controversial issues such as the Barbarous Jew of Malta, the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of Protestants in France and the homosexuality of King Edward II.

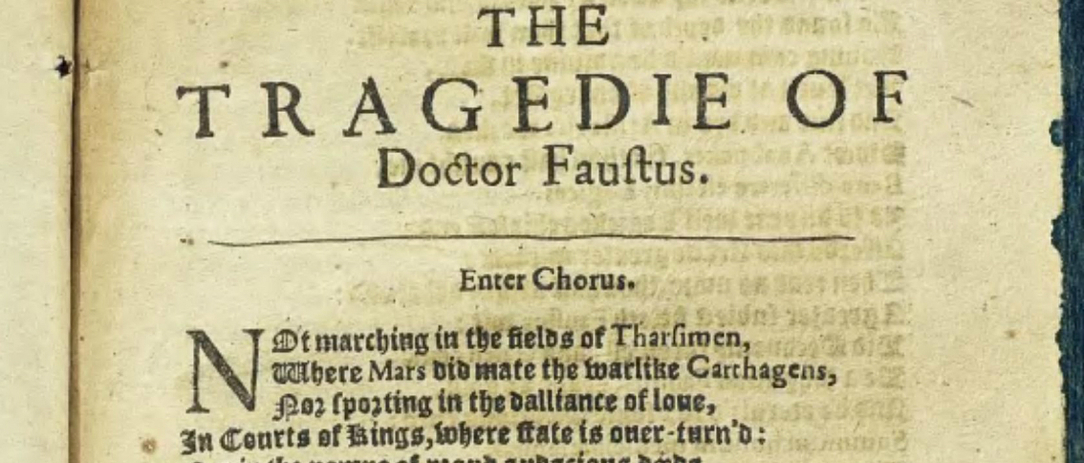

In the Tragical History of Doctor Faustus his protagonist who had sold his soul in a pact with the Devil is unable to repent forgiveness from God but is instead cast down into the bowels of Hell. His enemies, and by all accounts he had many, might have said that it was more biographical than at first appeared.

Marlowe was also one of the first English playwrights to write in blank verse, a style that was to be adopted by William Shakespeare and indeed it has long been suggested that Marlowe either wrote, or at least collaborated on many of Shakespeare’s plays. His experience of foreign travel, international espionage and political intrigue lends credence to this view. After all, Shakespeare is never recorded as having left the country and as a secret Catholic very wisely kept his distance from the political controversies of the day. But that is as far as the evidence goes.

In many respects it hardly mattered whether Marlowe collaborated with Shakespeare or not his plays were a great commercial success. This was in part due to the stage presence of William Alleyne, the outstanding actor of his day. Strikingly tall and with a voice that carried to the farthest reaches of any auditorium he was the actor that everyone wanted to see, and his collaboration and that of his Company – The Admirals Men – played a big part in Marlowe’s success. But away from the London stage Marlowe’s life remained as turbulent as ever.

In 1589, he was accused of murdering a man in a brawl and spent two weeks in Newgate Gaol before he was acquitted of the charge following an intervention by an unknown Government source; the same source no doubt that had previously prevented prosecution for various incidents of brawling, sodomy, and heresy.

In 1592, he was arrested in the town of Flushing in the Netherlands on a charge of counterfeiting. He had in fact been part of a plot to infiltrate dissident Catholic circles by providing them with coin and thereby winning their trust. Marlowe never faced trial after yet another intervention by a government source and was instead returned to England where all charges were subsequently dropped.

Marlowe whose errant behaviour was closely monitored now found that his fame as a playwright precluded his usefulness in the game of espionage. It was also possible that he knew too much.

In 1593, posters began to appear on the streets of London written in the style of Marlowe and many of which referenced his plays threatening the safety of Protestant refugees from the Continent who had settled there.

On 11 May, Thomas Kydd, a fellow playwright and close associate of Marlowe’s was arrested and seditious material that was found in his lodgings appeared to have been written in his hand. A week later on 18 May, a warrant was issued for his arrest.

On 20 May, he appeared before the Privy Council fearing the worst. But much to his surprise he was released and merely ordered to: “Give his attendance on their Lordships until he shall be licensed to the contrary.”

His relief was tempered by the fact that he was now a marked man and could be detained at any moment. He would have to be on his guard.

By 30 May 1593, Marlowe was staying at a house in Deptford owned by the widow, brothel-keeper and fellow spy, Eleanor Bull. He was sharing a room with three other men, Nicholas Skeres, Robert Poley, and Ingram Frizer, all of whom were known to have worked for Sir Francis Walsingham’s Intelligencer Network and to have had underworld connections.

They had been drinking all afternoon and Marlowe was lying on a couch when he and Frizer began to argue over who was expected to pay the bill. Marlowe, whom it was not difficult to rile, leapt from the couch and snatching a knife attacked Frizer causing a cut to his head. Frizer fought back and in the ensuing struggle stabbed Marlowe through the eye killing him instantly.

At least this was the version of events presented at the Coroner’s Inquest held two days later and as a result Frizer was deemed to have acted in self-defence and no charges were brought against him and after less than a month in confinement he was released.

In the meantime, Marlowe’s body was buried in an unmarked grave.

A great many people believe that Marlowe was assassinated, that his increasingly erratic behaviour had made him unreliable, that he knew too much and had become a security risk. Rather than risk the prospect of secrets being revealed it was easier to have him murdered.

Either way, at the age of just 29, the brilliant young playwright was dead and his mantle as England’s foremost man of letters passed to another, a contemporary, sometime collaborator, and no doubt rival – William Shakespeare.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: