Churchill Ousted

Posted on 4th June 2021

Tuesday, 8 May 1945, was designated V.E or Victory in Europe Day.

It had been a long hard struggle, but the defeat of Nazi Germany had been anticipated for some time and people had been preparing for this day with most department stores long having sold out of flags and bunting though the many hawkers who infested the streets of London and other major cities more than made up the difference selling all kinds of celebratory memorabilia at exorbitant prices.

A public holiday had been announced at very short notice which left some employers disgruntled and many workers unable to attend the planned celebrations but nevertheless the people were out on the streets early on what was a beautiful, sunny and unseasonably hot day at 75% Fahrenheit with cloudless skies and only the lightest of breezes.

Singing and dancing soon broke the early morning calm, and the celebrations were to go on all day with people quick to slake their thirst and most of the pubs and taverns had run out of beer by early evening but by this time many were already the worse for wear, and some of the behaviour would have made Satan blush.

Earlier that day, the Prime Minister Winston Churchill had lunched with the King before briefing the House of Commons and broadcasting to the nation, now the crowds massing on the streets of London wanted to see him – Winnie, the man who had won the war.

At 5.40 pm, along with other members of his wartime Coalition Cabinet he stood on the balcony of the Ministry of Health in Whitehall as thousands of people thronged the streets below clamouring to hear him speak. They roared their approval and chanted his name but fell silent as made to address them: “This is your victory,” he said, “It is not a victory of any party or any class. It is a victory of the great British nation as a whole.” Three cheers immediately followed before Churchill exuberantly joined in the singing of “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.”

A little later he repeated the performance alongside King George VI, Queen Elizabeth and the rest of the Royal Family on the balcony at Buckingham Palace and little could he have imagined at this moment of supreme triumph that just eight weeks later he would be out of Office.

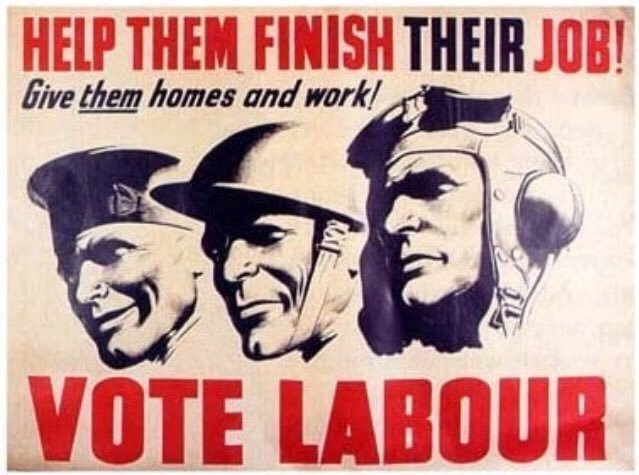

Not long after the V.E Day celebrations the Labour Party withdrew from the Coalition Government bringing it to an end. It had been decided that traditional party politics should resume as soon as possible and that the future direction of post-war Britain should be decided through the ballot box. The election date was set for 5 July, the first General Election in ten years.

Few people doubted that Churchill, the Great War Leader, the man who had led Britain through the darkest period in its history would win. Indeed, it was unthinkable that he would not but during the election campaign the old perceptions of Churchill began to re-emerge – Churchill the strike-breaker, the arch- imperialist, the military adventurer. Recent history did not erase the collective memory and it wasn’t necessarily a positive one.

Even during the 1930’s when he had been one of the few siren voices that had warned of German militarism and of the need to re-arm, he had been speaking at a time when the carnage and horror of the First World War remained fresh in the memory. He was thought by many to be a warmonger; and hadn’t he sent tanks onto the streets of Glasgow and ordered troops to shoot dead striking miners in Tonypandy? Many believed he had, and that he was no friend of working people that’s for sure.

The Labour Party had a plan for rebuilding Britain, though with the country almost bankrupt with what exactly remained a moot point; but they had adopted as policy many of the welfare reforms suggested in the Beveridge Report along with the creation of a National Health Service that would provide free healthcare for all at the point of delivery. They also intended a gradual withdrawal from British possessions overseas while Churchill remained firmly wedded to the concept of Empire. But it was homes that most concerned the people and was to be the dominant issue of the election.

During the war 3.25 million buildings had been destroyed, 92% of them residential dwellings and many millions of people were living in cramped conditions with relatives, in temporary accommodation or in low rent properties that bordered on the squalid. Labour had a plan to build cheap prefabricated homes for rent, the Conservatives did not.

Churchill’s insistence that economic growth long-term would see the domestic housing sector revive simply failed to convince those who were in desperate need of help in the here and now. He was also his own worst enemy and he made the campaign against his old coalition partners deliberately bitter and divisive as if he was fighting yet another military campaign.

His claim in a radio broadcast that for Labour to implement their plans they would have to create a political police force, a Gestapo, went down particularly badly even among traditional Conservative supporters. The very idea of comparing the uncharismatic Labour leader Clement Attlee, who had been Churchill’s deputy throughout the war with Heinrich Himmler was palpably absurd. Churchill however failed to heed the advice of both friends and supporters not to compare Labour’s plans for reform to the building blocks of a totalitarian State and continued to bang on about it throughout the campaign.

Warning against the implications of socialism was one thing but not having an alternative of his own was another and it seemed to many that all he was offering was a return to the conditions of pre-war Britain and that once again, just like after the First World War, those who had endured so much would be left fend for themselves.

Now 70 years of age the once vigorous wartime leader suddenly seemed old, the soaring rhetoric that had so lifted British spirits during the darkest days of the war had gone and his speeches were often lethargic and uninspired. He appeared tired and like a man out of step with his time who would be unable to provide the change, the new beginning that so many people desired.

Churchill should have been warned that all was not as it seemed after he was heckled and booed during a speech at the White City. Even so, he remained heedless of the advice he was being given to change his campaign strategy appearing distracted by the preparations for the invasion of mainland Japan and the forthcoming Potsdam Conference with Josef Stalin and the new American President Harry S Truman (Roosevelt had died in April).

In his final election broadcast on 30 June, after once more warning against the dangers of socialism he put to bed a rumour circulating that regardless of how the people voted he would still be retained as Prime Minister. He made it plain that if people voted for his political opponents they were also voting for his dismissal.

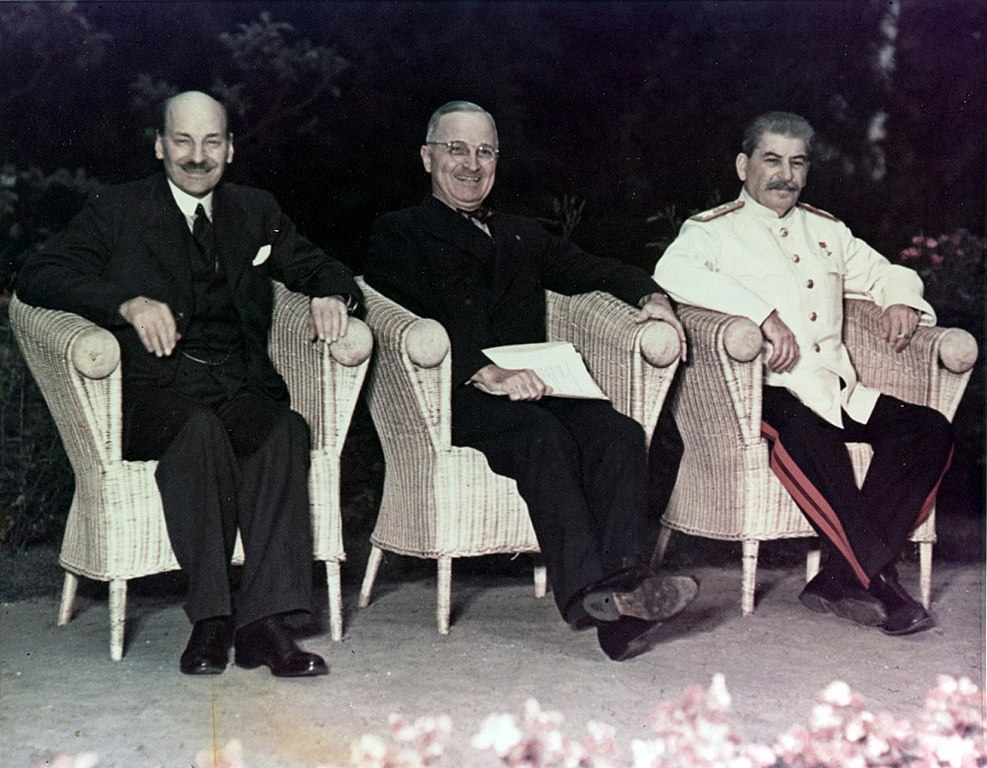

On 15 July, he travelled to Germany taking the Labour leader Clement Attlee with him. He was looking forward, he said, to masterminding the final victory over Japan and re-fashioning the post-war democratic world.

The result of the election was to be delayed for three weeks to allow ballots cast by servicemen still serving abroad to be returned to Britain and counted. As a result, the Khaki Election as it became known wasn’t expected to be completed earlier than the 26 July and so provided adequate time for Churchill to once more be the Statesman. While he was in Potsdam, he received regular reports of the count back in Britain and was reliably informed that he could expect a comfortable 80 seat Conservative majority. This was diluted over the next few days but never diminished to below at least a working majority.

The Potsdam Conference was still not over when Churchill and Attlee flew back to London for the election result. Upon his arrival he was reliably informed that he could still expect a 30 seat Conservative victory. If so, it was hardly a ringing endorsement of the man who had led the country through six years of hardship and war, nonetheless it would suffice.

As the individual results began to filter through and leading war time Tories such as Leo Amery, Harold McMillan, and Brendan Bracken lost their seats it became increasingly apparent that even this estimate was way too optimistic. Even Churchill’s son-in-law Duncan Sandys, lost his seat – it was an ominous sign. In Churchill’s own constituency of Woodford where out of respect neither the Labour nor Liberal Party had selected a candidate, 25% of the vote was won by a local farmer with no political experience running as an Independent the writing was on the wall.

When late on the 26 July, the BBC announced the final election result it was the culmination of Churchill’s worst nightmare. The British people had not just rejected him they had done so overwhelmingly handing the Labour Party a landslide victory.

Labour had won 393 seats and 47.8% of the vote to the Conservatives 213 seats and 39.8% of the vote and they had not only consolidated their hold in their traditional urban heartlands but had made great in-roads into the Home Counties and had won rural constituencies once considered way beyond their reach.

The deciding factor had it seemed been the Khaki vote for though only just over 50% of servicemen overseas returned ballots more than 60% of them voted Labour and it seems certain that if more of them had done so then the majority against Churchill would have been even greater. This time unlike the unfulfilled pledge of 1918, they really did want to return to homes fit for heroes.

In barely time to clear the bunting from the streets and with the war against Japan still not won Winston Churchill, the man whose name had been on everyone’s lips just a few weeks before had been unceremoniously booted out of Office with fewer than 4 out of every 10 of the electorate voting for him. After the glory of victory, the humiliation of defeat was total, and a pall of resignation descended upon a dumbfounded Churchill. When his wife Clementine dared to suggest that it was perhaps a blessing in disguise he somewhat snappily replied that if so then it was a very well disguised blessing but despite his disappointment in general he took the defeat well and when one of his advisers railed against the ingratitude of the British people he replied they’d had a hard time and that: “They are entitled to vote as they please. That is democracy. That is what we’ve been fighting for.”

When the British delegation returned to Potsdam with Clement Attlee as Prime Minister, Churchill remained at home.

The immediate post-war period remained a time of austerity and extreme hardship and the worst winter since records began almost brought the country to a standstill. Rationing continued and now included bread which hadn’t even been rationed during the war and it was to continue until 1955.

The new Labour Administration had a great deal to do and little money with which to do it, the war may have been won but it had left the country bankrupt.

Excluded from receiving help under the American Marshall Plan to re-construct war-torn Europe the Labour Government was forced to go cap-in-hand to Washington for a loan simply to prevent the country from disappearing into the financial abyss. They were to receive help, but the loan was for less than half of what they had asked for and believed they required. Regardless, they forged ahead with their plans for the Welfare State, the National Health Service, their House Building Programme and the Nationalisation of the Coal, Steel and Railway industries.

In the meantime, Churchill broiled in opposition as Attlee’s Labour Government changed the fabric and face of British society forever and even more to his chagrin began to dismantle the Empire, he so cherished and had fought for so long to preserve. Still, he remained a great hero and would often travel abroad to great acclaim warning of the threat posed to Free Europe by the Soviet Union and of an Iron Curtain dividing the Continent. He was also one of the more forward thinking men of his time suggesting the creation of a Federal Europe (Britain excluded) and the establishment of a European Army. The trouble was that he could only suggest he could no longer do.

But while he focussed on foreign affairs his domestic policy remained a wasteland of tired ideas and failed laissez-faire economics. And despite all the hardship the British people had been forced to endure in the years immediately following the end of the war on 23 February 1950, Labour was elected once more.

Though its majority had been reduced its share of the vote had increased and the British people had shown little enthusiasm for having Churchill back. Still, he regularly mocked Attlee as “a modest little man with much to be modest about.” But it was the undemonstrative Clement Attlee who was re-fashioning Britain not the Great War Leader.

Much to the annoyance of his senior colleagues the 76-year-old Churchill refused to resign his leadership of the Conservative Party. He knew that the Labour majority in the House of Commons would be whittled away overtime and that another election would have to be held not too far down the road.

He was right and on 25 October 1951, the country once more went to the polls and despite Labour receiving more of the ballots cast the country’s first-past-the-post electoral system worked in the Conservatives favour and they won a slim 26 seat majority. It was a personal triumph for Churchill, if a somewhat muted one.

As a great many people suspected his second term as Prime Minister was dominated by foreign affairs, and little was done to improve the lot of the British people. His Premiership was not deemed a success as often ill he struggled to cope with the minutiae of administration and on 23 June 1953, he suffered a massive stroke. It was kept a secret from the British people and many close to him thought he would die but miraculously and displaying the bulldog spirit that during the war he had come to epitomise he recovered sufficiently to be back at work within a few months. But his time at the forefront of British political life was drawing to a close.

On 5 April 1955, at the age of 81 Churchill resigned as Prime Minister in favour of his Foreign Secretary and long-time heir presumptive, Anthony Eden.

Always the maker of his own destiny Winston Churchill drew the veil over a political career spanning almost 60 years, though some might justifiably argue that the British people had effectively done this for him ten years earlier in that seminal election when they denied him any role in their future.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: