Clive of India: Making an Empire

Posted on 8th May 2021

As a young man he had been a bully and a thug, in later life he was accused of being venal and corrupt; but he was also a brave, audacious, cunning and resourceful man who against seemingly impossible odds and almost single-handedly would snatch for the British Empire what was to become its Jewel in the Crown.

Robert Clive was born in Styche, a small village near the town of Market Drayton in Shropshire into an old and well-established family of the Shires and his father, a lawyer, had for many years been the local Member of Parliament.

From the beginning Robert was a young man on the make and though he had been raised in some comfort in a Manor House he remained determined to make his own fortune, a fortune that for him could never be too big.

He was by any modern definition a tearaway, even a delinquent who was expelled from every school he ever attended and spent his time terrorising the local population even running a protection racket where he and his adolescent enforcers demanded money from local merchants as the price for not vandalising or burning down their premises. It was the case that most paid up and he was making a tidy packet. But as far as his family were concerned, he was an embarrassment and no amount of punishment seemed able to deter him from his actions or change his behaviour. In their desperation his family secured employment for him with the East India Company. They told him that in India he could make his fortune, but in truth they just wanted rid of him. So, in 1744 aged 18, and somewhat reluctantly, he set sail for the Indian sub-Continent.

The life expectancy of Europeans exiled to India was not high with more than 50% dying within three years of their arrival in the country and the young Robert Clive soon came to understand why. His was a life of drudgery, he worked for long hours in extreme heat for very low pay and the tedium of the work drove him to distraction. He was not considered a good worker and was in constant trouble with his employers.

He was also a manic-depressive who soon took to opium as an escape from the grim reality of his life and it was to become an addiction which he never shed. Bored beyond all measure and in a dark place from which there seemed no escape he resolved to kill himself. He put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger, but it failed to go off. He repeated the exercise but the same happened again. He later said that he took this as a sign from God that he was being saved for something special. So, he continued in his post, bored, lazy, and irascible; dreaming of riches and of how to make them. But it was to be events far away in Europe that were to determine Robert’s future when the War of the Austrian Succession was carried overseas and an opportunity presented itself for those audacious enough to take it, and Robert Clive was nothing if not audacious.

On 4 September 1746, the city of Madras was attacked by the French and quickly surrendered. During the lull between its surrender and the French occupation of the city Clive organised the escape of himself and his colleagues to the nearby Fort St David. His courage was duly noted and he was granted a commission in the East India Company’s Army but much to his disappointment following the restoration of peace in 1748 he was returned to the tedium of his office and a period of sustained depression soon followed.

But Clive’s willingness to take the initiative and chance his arm had not been forgotten and he was soon to make his mark again at the Siege of Arcot in 1751.

Although Britain and France were officially at peace, they continued to wage war by proxy in India and Chanda Shahib, an ally of the French had laid siege to the city of Arcot. Clive in an act of shameless self-promotion now declared that provided with the means to do so he would raise the siege. Considering the events at Madras the East India Company agreed though they could not provide him with very much. His army would consist of just 200 European troops, 300 Indian sepoys, and 3 cannon.

Clive bided his time and captured the fort at Arcot under the cover of a thunderstorm. He was then besieged himself for 50 days before a relief force of 2,000 Maratha Cavalry under the command of Madina Ali Khan, an ally of the British, lifted the siege. Clive’s capture of Arcot and his successful defence of it brought to an end the campaign in the Carnatic region of India securing both a favourable peace for Britain while also increasing her possessions in southern India.

He returned to Britain in 1753 a national hero and was even praised in the House of Commons by the then Prime Minister William Pitt as a ‘Heaven sent General.’ But he was not to remain in Britain very long, still ambitious he knew that there was much more glory and money still to be made on the Indian sub-Continent.

Robert Clive returned to India in 1755, no longer a lowly clerk but as Deputy Governor of Fort St David. His return also happened to coincide with the accession of Siraj-ad-Daulah as the new Nawab of Bengal. The newly enthroned Nawab made no attempt to disguise his contempt for the British and was determined to assert control over his own territory and on 20 June 1755, he attacked and took the British held city of Calcutta.

By the time of its fall most of the European inhabitants had already fled but those who remained, some one hundred and forty-six souls, were rounded up and imprisoned in a tiny cell just fourteen feet by eighteen feet with one small window for air. According to one of those imprisoned the surgeon John Zepheniah Holwell: “By nine o’clock several had died, and many more were delirious. A frantic cry for water now became general, and one of the guards, more compassionate than his fellows, caused some to be brought to the bars, but in their patience to receive it nearly all was spilt, and the little drank only seemed to increase their thirst. Self control was soon lost, those in the remote parts of the room struggled to reach the window, and a fearful tumult ensued, in which the weakest were trampled or pressed to death. They raved, fought, prayed, blasphemed, and many fell exhausted to the floor, where suffocation brought an end to their torments.”

In the heat of an Indian High Summer many did indeed die from heat exhaustion or were trampled to death in their desperate attempts to find some air. By the time Siraj-ad-Daulah ordered their release the following morning 123 of them were dead.

We only have Zepheniah Holwell’s account for what really happened but even taking into account his tendency for exaggeration the “Black Hole of Calcutta” was a cruel and brutal act.

An outraged Britain cried out for vengeance and Robert Clive was just the man to provide it and his reputation was such that he was immediately put in command of operations to recapture Calcutta. Again, his army was small, just 2,000 infantry, but this time he was supported by a naval squadron commanded by Admiral Charles Watson.

Clive wasted little time taking the fight to the Nawab’s much stronger army and his aggressive tactics worked forcing him to abandon Calcutta on 5 February 1757.

Siraj-ad-Daulah remained unperturbed by his defeat however and was determined to renew hostilities with the British but this time with French support. Clive had also not been idle and unknown to the Nawab had been in negotiations with the commander of his army, Mir Jafar, who was opposed to his alliance with the French.

Mir Jafar was extremely ambitious something that Clive was quick to exploit, and he agreed to consent to him replacing Siraj-Ad-Daulah as Nawab of Bengal in return for his support in any ensuing conflict. Mir Jafar would also make substantial payments totalling hundreds of thousands of pounds to the East India Company, its army, its officials and to Clive himself. This treaty, which was kept secret both before and after it was signed has since been used against Clive condemned as he later was for his greed and duplicity.

Aware that long and tiresome negotiations between the East India Company and Siraj-ad-Daulah had broken down and that the renewal of hostilities was imminent, Clive decided to take the initiative. He advanced his army (the Europeans in boats down the River Hooghly, his Indian sepoys made to walk) to confront the army of the Nawab. He established his headquarters in a hunting lodge in the mango groves of Plassey and awaited the Nawab’s response.

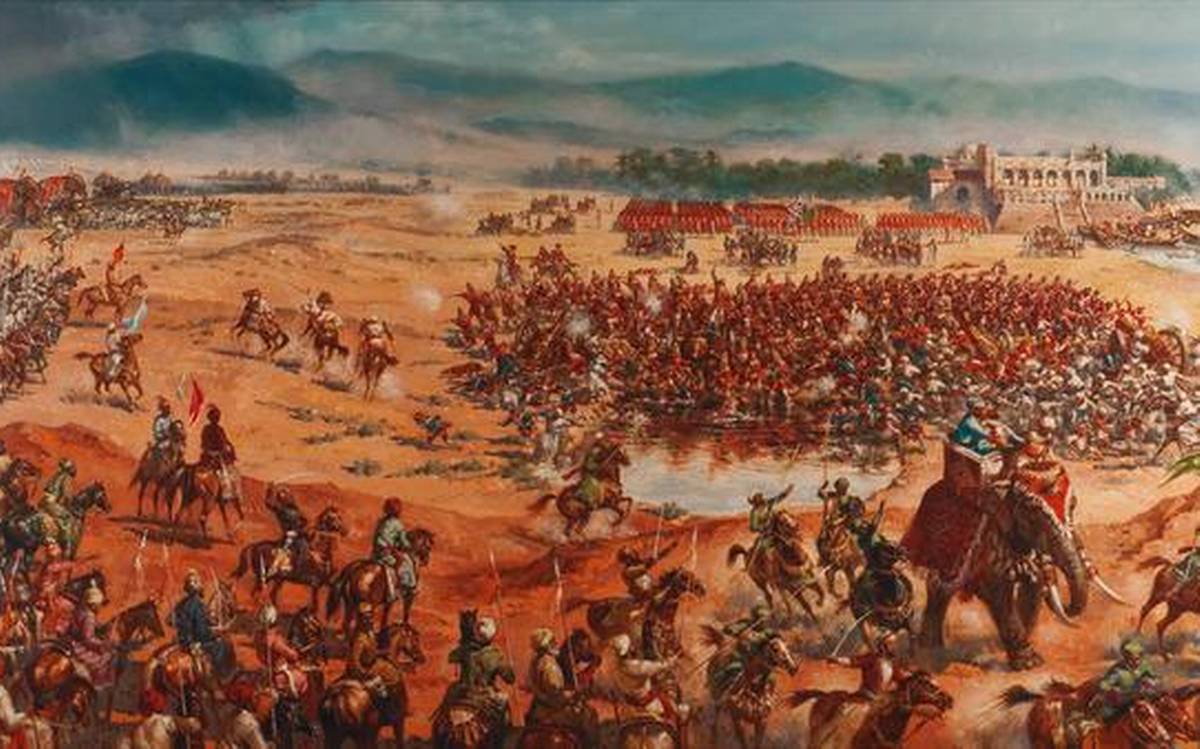

As usual his forces were slight 1,100 European troops supported by 2,100 Indian sepoys and 9 cannon. The Nawab’s army was massive by comparison, and he could put in the field 50,000 infantry, 18,000 cavalry, War Elephants and 53 cannon manned by French gunners.

Seeing the forces arrayed against him Clive for the first time in his life demurred – to attack such an overwhelming force would be madness and that night he held a Council of War and told his Senior Officers that they were to decide: “Whether in our present position without assistance it would be prudent to attack the Nawab or whether we should wait to be joined by some other power?”

A vote was taken, and Clive supported those who counselled caution. The outcome of the ballot was 9 to 7 against an immediate attack but Admiral Eyre Coote who was adamant they must strike first and quickly, berated Clive for his loss of nerve.

Sometime during the night Clive had a change of heart. He was to say it came to him in a dream, others have suggested that he was concerned for his reputation as a man of courage, or maybe he just trusted in Mir Jafar. Whatever the reason, on the morning of 23 June 1757, he advanced his army to confront Siraj-ad-Daulah.

In swelteringly hot conditions and with an almost impenetrable haze hanging over the battlefield both sides manoeuvred and exchanged artillery salvos, but very little actual fighting took place. Late in the day Mir Jafar led his forces from the field of battle and witnessing this the remainder of the Nawab’s army simply disintegrated.

Robert Clive had won one of the most decisive battles in world history for the loss of just 22 sepoys killed and 50 wounded. The Miracle of Plassey marked the beginning of British control of the Indian sub-Continent and the creation of the Raj, the Jewel in the Crown of the British Empire. Though there would still be much hard work and much hard fighting to be done.

Following his victory at Plassey, Clive was made Governor and continued to advance and consolidate British rule in Bengal and beyond. Yet at the age of just 35 he was already suffering from constantly failing health and his bouts of depression were becoming more regular and sustained. Neither of which prevented him from continuing to accumulate great wealth and by the time he returned to England in 1760 his personal fortune was estimated to be worth no less than £300,000.

Back in London he was greeted as the all-conquering man of genius, the Hero of the Empire who subdued continents, and he was showered with accolades and honours. He was also praised repeatedly in Parliament, was received at Court and ennobled Baron Clive of Plassey.

In his absence from India however the efficient Administration he had left behind had been become mired in sleaze and corruption, and by April 1765 he had once again set sail for India.

The first thing he learned upon his arrival three months later was that Mir Jafar, who after Plassey had murdered Siraj-ad-Daulah and replaced him as Nawab of Bengal, had died leaving him £70,000 in his Will. After receiving and pocketing the bequest he passed a law banning the acceptance of gifts by civil servants from native Indians. His attempts to clean up the Administration were largely unsuccessful however, and though he did his best to reform the army, reduce the extortionate levels of taxation imposed on the peasantry and tried to stamp out smuggling by the time he left India for the last time in February 1767, very little had changed.

Though he had been away for less than two years he was to find the atmosphere in England very different to the one he had left behind. The praise previously lavished upon him had turned to criticism. His fame, great wealth and inflated status had induced feelings of envy and mistrust in many of those who mattered. That a man of no background should fly so high went against the grain of the established order. The qualities required for so great an elevation simply could not exist in a man of such common stock.

From 1772 onwards he was forced to defend himself from attacks upon his honesty and integrity from all sides of the political spectrum. He was pilloried in the press for his greed, accused of taking bribes, placed under investigation, and made to justify his actions in the House of Lords. When questioned in Parliament about the vast wealth he had acquired in India he replied: “By God, I am astonished at my own moderation.”

Despite being cleared of all charges the constant hounding from those he had previously considered friends, their jealously, snobbery and lack of gratitude, had taken its toll on the always emotionally fragile Clive. Depressed and suffering from acute abdominal pains he was found dead in his home on 22 November 1774. He had slit his own throat.

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: