Countess Markiewicz

Posted on 15th September 2021

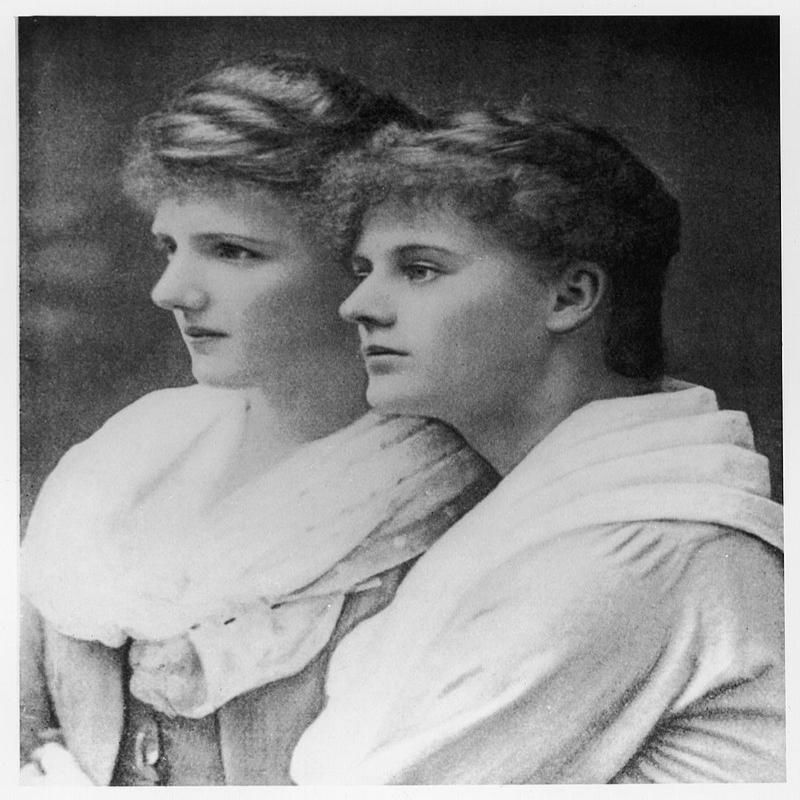

Born on 4 February 1868, Constance Georgine Gore-Booth was an English aristocrat raised in Ireland who as beautiful and graceful as one might expect could have lived a decorous life; that she chose not to can be worthy of praise but the manner of her choosing no less worthy of criticism for she took up arms in the cause of Irish freedom thereby conspiring against the country of her birth and committing treason.

Her parents Sir Henry and Lady Georgina Gore-Booth were of Anglo-Irish stock and owned estates in County Sligo where unlike many of the English landowning class in Ireland they enjoyed a good relationship with their tenants and were well respected locally. Liberal in their politics they also allowed their daughters a freedom to roam which Constance took full advantage of indulging her passion for the outdoors learning to ride, hunt, and fish. Indeed, she loved her childhood in Sligo, its landscape, the fresh air and all the other myriad attractions of a carefree life in rural Ireland. It was a privileged existence, and she no less enjoyed being the pampered young lady as she did the self-indulgent tomboy of her daytime meanderings.

As she grew older and became increasingly accomplished, she attracted a great many male admirers and even impressed the not always amenable Queen Victoria when presented to her as a possible paramour for her grandson the future King George V, but she had no relish for the ornamental life. She wished to achieve things in her own right, though what exactly remained a mystery.

Whatever it might be it certainly didn’t appear to involve politics for she showed little interest in the social movements of the day and would yawn her displeasure whenever her more engaged younger sister Eva discussed such issues as labour reform, improved living conditions, and even women’s suffrage.

So she rejected political activism for art studying first in London and later Paris and it was in Paris that she first met Count Casimir Markiewicz, a Ukrainian aristocrat of Polish descent and not very successful playwright and theatre director who nonetheless was a familiar figure among the artistic milieu of the city introducing Constance to a bohemian lifestyle of which she neither approved nor disapproved but did think decidedly un-English.

Even so, able now to live outside the rigid social conventions of the day while still attending the Ambassador’s Ball suited her well, and it helped her relationship with Casimir blossom, that was until they married in September 1900.

Constance gave birth to a daughter not long after the wedding and in 1903 the now Countess Markiewicz and her husband returned to Ireland but despite being back in more familiar surroundings she could not adapt to domestic life; she was not equipped to be a mother neither was she a dutiful wife. It was not enough, she needed some purpose, some reason to exist, and her frustration was placing an intolerable strain on the marriage. In 1905 she wrote: “Nature should provide me with something to live for, something to die for.”

It was this dissatisfaction with life that led the Countess Markiewicz into politics.

By 1905, she and Casimir were living in Dublin where working as a theatre director he staged a number of plays in which Constance acted alongside Maud Gonne the unreciprocated love interest of the nationalist poet W.B Yeats. It was Maud who was to introduce Constance to radical circles where the promotion of the Gaelic language and preservation of Irish culture dominated literary output and was always the prevailing topic at any dinner party worthy of attendance.

Constance soon became an advocate for this resurgent Ireland, but it wasn’t until the following year having read many of the pamphlets then circulating which called for Irish independence from Britain that her cultural nationalism became political.

In 1908, she joined Maud Gonne’s radical Daughters of Ireland and a little later the recently formed nationalist party Sinn Fein – at last she had found that elusive purpose for life, a cause to fight for, and yes, to die for.

Not that she was entirely trusted by her new colleagues. She was after all a lady, English, and a Protestant. Turning up for her first party meeting in a ball gown and a tiara having just attended a party at Dublin Castle the seat of British power in Ireland, didn’t help; but she was soon to prove the sceptics wrong and that she was more than a merely decorative fellow traveller.

She had been radicalised, and soon after travelled to England to harass Winston Churchill during the Manchester North by-election campaign over his refusal to support women’s suffrage. Her impact was minimal, but this did little to diminish her delight at his defeat. There was always something about Churchill that brought out the worst in his opponents.

But this was just the beginning for Constance as she threw herself into the cause she now believed in utterly working assiduously at every level from distributing leaflets, to sitting on committees, and addressing rallies. In 1909, she helped found Fianna Eireann, a front organisation for providing young men with military training and for which she made land available on the family estate. Her social connections would indeed prove of great value to the movement and by 1911, she had been drafted onto the Sinn Fein Executive.

The situation in Ireland which so often appeared like a powder keg ready to explode was only inflamed further by the Liberal Government in Westminster introducing a Home Rule Bill intended to establish a bi-cameral Irish Parliament elected by Irishmen to administer Irish affairs. It was the third attempt in as many decades to secure a settlement for Ireland, but it was to prove no less problematic than the previous two.

Protestant Unionists in the north of the country refused to be governed by a Catholic dominated Parliament based in Dublin. Under the leadership of Sir Edward Carson (who earlier as a barrister had prosecuted Oscar Wilde) they founded an armed militia the Ulster Volunteers, and on 28 September 1912, he presided over the ceremony that saw 500,000 Ulster Unionists sign the Solemn League and Covenant which vowed to oppose the attempt to introduce Home Rule by any means possible.

In response to the belligerency of the Ulster Unionists in the north nationalists in the south also formed their own armed militia, the much larger Irish Volunteer Force. Ireland seemed on the brink of civil war.

Unlike on previous occasions the Government appeared ready to face down the Unionist opposition to Home Rule by force, if necessary, but doubt was cast upon their ability to do so when in May 1914 letters were received indicating that senior Officers of the British garrison based at the Curragh in County Limerick would resign their commissions if ordered to act against the Unionists in Ulster. The Curragh Mutiny as it became known sent a shiver down the spine of the British Establishment and it seemed as if an impasse had been reached. But while the Navy was being prepared to sail to Belfast and do if necessary, what the Army could not be trusted to do war broke out on the Continent.

The Great War changed everything, or so it seemed, and when the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party John Redmond agreed to the shelving of the Home Rule Bill for its duration (expected to be a year) and called upon Irishmen everywhere to support Britain’s war effort it seemed that the crisis was at an end. But it had only been stymied and passions continued to run high. Redmond’s commitments had served to split the nationalist movement and more militant elements now came to the fore with their hopes raised rather than quashed by events.

Home Rule aside Ireland was no more immune to the rural unrest and industrial strife that beset mainland Britain in those turbulent months before the outbreak of war with Constance active in the many of the disputes. She worked closely alongside the trade unionist leader James Connolly in setting up soup kitchens in Dublin and organising collections for the strikers.

Times were tough yet despite this and the continuing rancour and division caused by the proposed Home Rule Bill there was little enthusiasm for independence. But the war provided an opportunity for it weakened Britain and made the prospect of finding allies among her enemies willing to support Irish independence more likely.

Germany had indicated it would provide arms and ammunition in preparation for an uprising. Should such a rising prove successful they might even invade. It was enough to convince the nationalist leadership to make their bid and strike for freedom.

On 24 April 1916, Padraig Pearse, leader of the Irish Republican Brotherhood stood upon the steps of the General Post Office in O’Connell Street, Dublin, and read out his Proclamation of the Irish Republic: “In the name of God and the dead generations from which she receives her tradition of nationhood, Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag and strikes for freedom.”

The operation had been carefully planned and he had 1200 armed men behind him willing to fight but with little popular support Pearse knew the chances of success were slight; Still he was convinced that a blood sacrifice was required and that Britain’s response to any rebellion would be swift, harsh, and vengeful – he was right. In the midst of a foreign war, they were not about to countenance rebellion at home. Troops were despatched from the mainland to reinforce the local garrison and when the demand the rebels lay down their arms was refused the hostilities began.

The fighting was fierce with the determination of the rebels was more than matched by the anger of the British and Constance was in the thick of it. Stationed at St Stephen’s Green it was said she had been appointed second-in-command which may not have been entirely accurate, but she was certainly prominent overseeing the positioning of troops, the building of barricades, and the distribution of ammunition before taking up arms herself. A nurse who was taking shelter nearby later described in her diary:

“A lady in a green uniform holding a revolver in one hand and a cigarette in the other was standing on the footpath giving orders to the men. We recognised her as the Countess Markiewicz. We had only been looking a few minutes when we saw a policeman walking down the path. He had only gone a short way when we heard a shot and saw him fall forward onto his face. The Countess ran triumphantly into the Green shouting – I got him!”

If the writer’s account is accurate, then she had just shot an unarmed man without warning who later died of his wounds.

It had been hoped, forlornly perhaps, that once news of the armed insurrection in central Dublin spread it would create in its wake similar events elsewhere in Ireland but no reports of such reached the rebels and while Dubliners ventured to look, they chose not to participate. The rebellion then had not been the spark that would set Ireland ablaze, that would rouse the people to rise up and expel the foreigner from its blood soaked but sacred soil, to revive and restore once more the freedom and liberty of the Gaels sojourned for so long in the mists of time. Such was the rhetoric of romance, the romance no doubt that drew an English Countess to the cause of Irish nationhood. But there is little romance in the crash of an artillery shell and he rat-tat-tat of the machine gun.

By establishing themselves in fixed positions that were easily cordoned off and surrounded the rebels had foregone any freedom of movement and could not be reinforced or resupplied. Without support from outside the end was inevitable. Even so, the ferocity and determination with the Irish fought surprised the British who having seen their attempts to storm their positions repulsed would resort to siege and high calibre explosive shells – the rebels would either starve or die in the rubble

.

After six long days and with the British poised to use even heavier artillery, maybe even warships moored on the River Liffey, to which the rebels had no answer and with ammunition running low and casualties mounting on 29 April, in order to avoid further bloodshed and needless loss of life, Padraig Pearse agreed to an unconditional surrender.

This would not be the end of his intended blood sacrifice, however.

As the captured rebels were marched through the streets of the city they were shocked to find themselves jeered at and spat upon by a people hostile to their aims and unsympathetic to their plight – they had expected better. The Easter Rising as it was soon to become known was not after all a terrorist attack or an incident of guerrilla warfare, nor was it intended to be. They had announced who they were, declared their aims, had a command structure, some wore uniform, and they all acted under orders - they were an army, a citizen army, an Irish Republican Army, and had fought the enemy in the open after a formal declaration of intent. They had expected to be treated as prisoners-of-war but were in fact to be considered traitors to the crown.

During the first two weeks of May 1916, a series of military tribunals sentenced 90 of the captured rebels to death among them the seven signatories of the proclamation and the Countess Markiewicz. Unlike the 15 who were to be executed by firing squad in the courtyard of Kilmainham Prison, Constance, who’d had the dubious honour of being able to surrender to her own cousin and was the only one of the more than 70 women taken prisoner to be kept in solitary confinement, to preserve her dignity it was said, was to be spared such harsh treatment. Her sentence was commuted to life imprisonment on the grounds that she was a woman, not a factor that seemed to trouble the criminal courts greatly in passing judgement on capital cases.

The decision of the military authorities in Ireland to execute the leading rebels was obtuse and counter-productive in effect making the rebel’s case for them by rallying an apathetic Irish people behind the cause of national independence.

The Government in Westminster soon realised its mistake and Constance, along with the other prisoner were released just a year later following a general amnesty. But it was to prove too little too late.

Despite her work on behalf of the nationalist cause and participation in the Easter Rising there were always those within Sinn Fein who viewed Constance Markiewicz as an outsider and not an entirely trustworthy one. As such, she often felt the need to re-assert her credentials and so upon her release from prison she converted to Roman Catholicism despite having not previously expressed any deep religious faith.

She also immediately re-entered the political fray and was briefly imprisoned once again this time for opposing the Military Service Bill which sought to extend conscription to Ireland but was released in time to campaign for the seat of St Patrick’s Dublin in the General Election of December 1918 which she duly won thereby becoming the first woman elected to the British Parliament.

She wasn’t to be the first woman to serve in the House of Commons however, for like the other 72 members of Sinn Fein elected she refused to take the Oath of Allegiance to the Crown and so was unable to take her seat. That honour would later go to the American born Nancy Witcher Langhorne or Viscountess Lady Astor.

The Election which had seen Sinn Fein take 73 of 105 Irish seats provided them with a political legitimacy and moral force unimaginable just two years earlier and they were determined to use it. Having chosen to ignore the Parliament at Westminster they now established their own the Dail Eireaan (Assembly of Ireland) which met for the first time on 21 January 1919.

The issue of Home Rule which had so dominated politics prior to the Great War was by now a dead letter and there seemed no possibility of Britain relinquishing its control over Ireland or tolerating any notion of dual power. A tense stand-off ensued which following a series of terrorist incidents descended into an undeclared war of independence between the British Armed Forces and the Irish Republican Army led by Michael Collins.

Such was Countess Markiewicz’s fame she was unable to play an active role in the war and remained for the most part in hiding but she stood firmly by the activities of the I.R.A and its elusive and charismatic leader. Her admiration for Collins wouldn’t last, however.

The war, though not the violence, would end with the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

Michael Collins had headed the Irish delegation sent to London to negotiate the end of the conflict but the treaty he signed which detached the six Protestant dominated northern counties from the rest of Ireland and kept the new Free State within the Commonwealth was simply unacceptable to many within the nationalist movement and their de facto leader, President of the Dail, Eamon de Valera.

The treaty was ratified at a stormy meeting of the Dail on 7 January 1922 but only just by 64 votes to 57. The violence of the debate made it clear there was little room for reconciliation and Constance argued furiously with Collins accusing him of being a traitor to which pointing at her he responded more than once, “You are English! You are English!” The anti-treaty faction then walked out – Civil War would follow.

Though it would cost Michael Collins his life the war between the newly constituted Irish Free State and the anti-treaty forces would be an uneven struggle. Constance, who sided with the rebels, would again find herself imprisoned, this time by people she had previously fought alongside.

The Civil War was a sad denouement to the long struggle for Irish independence but in the end an Irish State would exist, not over the entire island perhaps, but over those parts which wanted and had voted for it.

Following the end of the Civil War, Constance joined Eamon de Valera’s Fianna Fail Party for whom she was elected to the Dail in 1927, but she was not fated to serve as a peacetime politician. On 15 July following a short illness she died, aged 59.

The Countess Markiewicz had been a steadfast figure on the left of the nationalist movement at a time of great uncertainty and often discordant debate even if some doubted her commitment and were never convinced that it was more than a fad or the distraction from bored nobility. Those who worked closely alongside her knew otherwise however, and Eamon de Valera was present at her bedside as the end neared.

Her contribution then was acknowledged even if the obituaries were often less than flattering. But even among her enemies there was a grudging respect, as the playwright Sean O’Casey, not always an admirer wrote: “One thing she had in abundance – physical courage, with that she was clothed as if in a garment.”

Reconciled though she was to the Free State by the time of her death there was to be little official commemoration of her passing and certainly no State Funeral as had been requested. She was instead buried in a private ceremony at Glasnevin Cemetery with some of her previous colleagues in attendance, but certainly not all.

Share this post: