Coventry Patmore: The Angel in the House

Posted on 1st March 2021

The Angel in the House is arguably one of the most influential poems ever written but then it was always intended to be more than just a poem. It is a long, sentimental and sometimes rambling love song to woman, the ideal woman and the perfect wife as seen through the eyes of her admiring husband. She was devoted, obedient and subordinate to her husband in all things.

Dependent upon his wise counsel in matters unrelated to hearth and home and with no thought or ambition to do other than serve him. It is of course never as simple as that and there is a journey to be followed and a relationship to be formed but the Angel’s wings are true and it is the spiritual role of the woman to bring man closer to God - She is the butterfly fluttering in the breeze, beautiful to gaze upon but fragile in one’s hands, to be protected, cherished, and adored.

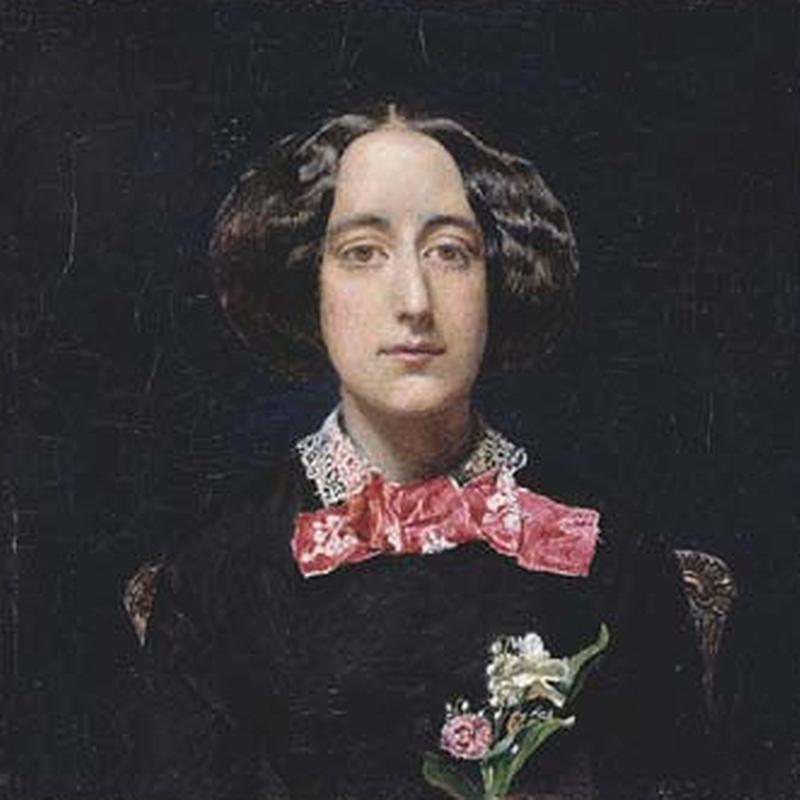

It was written in 1854 in tribute to his wife, Emily, whom Patmore believed to be the best a woman could be and an example for others to follow. Her portrait was later painted by John Everett Millais. Patmore who worked at the British Museum often frequented by William Morris and Dante Gabriele Rossetti among others was a close friend to many of the pre-Raphaelite artists and contributed several of his poems to the movement.

The Angel in the House was largely ignored at the time of its publication but grew in popularity in the decades following and came to represent the model of Victorian womanhood by which all women were to be judged though whether the poem reflects common attitudes towards women at the time or served to develop and cement them remains a matter of conjecture.

The Angel in the House for good or ill has certainly become synonymous with and a by-word for the role and status of women in Victorian society.

What follows is an extract from the poem both apt and telling:

The Paragon (Book One)

But when I look on her and hope

To tell with joy what I admire,

My thoughts lie cramp'd in narrow scope,

Or in the feeble birth expire;

No skill'd complexity of speech,

No simple phrase of tenderest fall,

No liken’d excellence can reach

Her, the most excellent of all,

The best half of creation’s best,

Its heart to feel, its eye to see,

The crown and complex of the rest,

Its aim and its epitome.

Nay, might I utter my conceit,

'Twere after all a vulgar song,

For she's so simply, subtly sweet,

My deepest rapture does her wrong.

Yet is it now my chosen task

To sing her worth as Maid and Wife;

Nor happier post than this I ask,

To live her laureate all my life.

The Wife’s Tragedy (Book One)

Man must be pleased; but him to please

Is woman’s pleasure; down the gulf

Of his condoled necessities

She casts her best, she flings herself.

How often flings for nought, and yokes

Her heart to an icicle or whim,

Whose each impatient word provokes

Another, not from her, but him;

While she, too gentle even to force

His penitence by kind replies

Waits by, expecting his remorse,

With pardon, in her pitying eyes;

And if he once, by shame oppress’d,

A comfortable word confers,

She leans and weeps against his breast,

And seems to think the sin was hers;

Or any eye to see her charms,

At any time, she’s till his wife,

Dearly devoted to his arms;

She loves with love that cannot tire

And when, ah woe, she loves alone,

Through passionate duty love springs higher,

As grass grows taller round a stone.

Jane to Her Mother (Book One)

Mother, it's such a weary strain

The way he has of treating me

As if 'twas something fine to be

A woman; and appearing not

To notice any faults I've got!

Share this post: