Custer's Last Stand

Posted on 17th March 2021

For a century after his death George Armstrong Custer was an American hero, vain and reckless perhaps but a determined and courageous soldier who met a noble end. In the post-Vietnam era, he has been demonised as an Indian hating adventurer interested only in glory and careless with the lives of his men.

The truth is rarely so complex and temporarily promoted to the rank of Major-General during the Civil War it was said he charged the enemy and trusted to luck. On 24 June 1876, on the blood-soaked banks of the Little Bighorn River his luck ran out.

He was born in New Rumley, Ohio on 5 December 1839, one of five children sired by the blacksmith. It was said his family were descended from a Hessian soldier who had fought for the British during the War of Independence and that this had never been forgotten. He was to remain close to his family even though for much of his young life he was raised by relatives in the nearby town of Monroe but this fact aside he had a fairly conventional upbringing.

Known as Autie from the problem he had pronouncing his middle name he was a show-off, and prankster with the reputation as a bully. Often in trouble he didn’t perform well academically at school and the prospect of a career of any substance appeared unlikely.

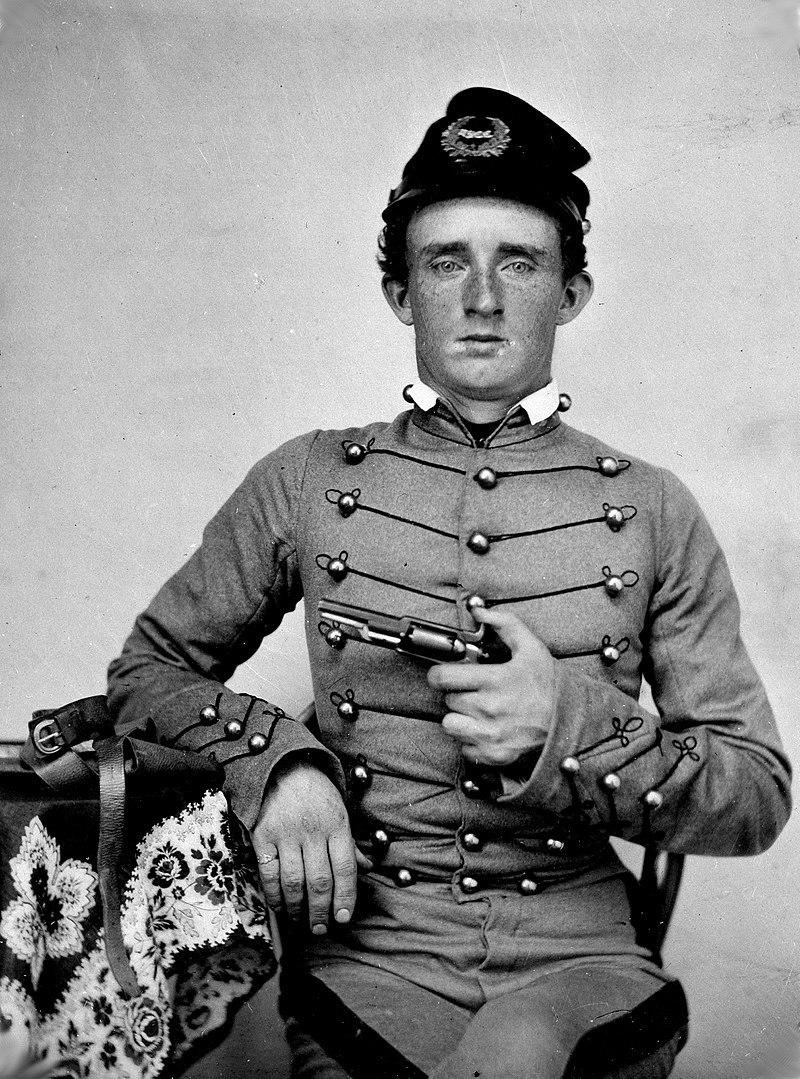

His father, who had wanted him to join the clergy was disappointed but young George had already made it clear that he desired a career in the military and given his failure to impress at school this seemed the best option, but it was difficult for someone of such humble background to gain admittance to Officer Training School. The Custer’s were politically active however, and it was through their political connections and their acquaintance with the local Republican Senator that in the summer of 1857, George was able to enrol at West Point Military Academy in Virginia. He was to prove a poor Cadet and performed no better at West Point than he had at school. He lacked concentration, rarely listened, and was ill-disciplined. Indeed, he was to acquire more demerits that any Cadet ever had and came close to expulsion on several occasions.

When he finally graduated in early 1861 it was as bottom of his class, but he was fortunate that his graduation coincided with the outbreak of the Civil War otherwise a career of military obscurity would have appeared to beckon.

In the years immediately preceding the Civil War, Custer, a fervent Democrat had been vocal in his support of the Southern cause. Never shy to express an opinion he was a fervent pro-slavery man and most of his friends at West Point had been Officers from the Southern slave-owning States. Even so, he did not believe in the break-up of the Union and when war was declared he remained loyal.

He was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the United States Cavalry joining the 3rd Michigan Brigade also known as the Wolverines and his wartime career was to be one of considerable self-promotion, no little glory, and rapid promotion. He was to be involved in some of the most significant engagements of the war and serving under General Philip H. Sheridan in his Shenandoah Campaign he fought at the battles of Brandy Station, Trevillian Station, Yellow Tavern, and Five Forks. He also led the charge that halted a flanking movement by Jeb Stuart’s Confederate Cavalry at the Battle of Gettysburg which proved pivotal in the Union victory something he was to make much of this in future years. That he survived such bloody engagements when he was an advocate of the headlong charge was a miracle, even if many of his men were not so fortunate.

By April 1865, he had been promoted to the temporary rank of Brevit Major-General and at the age of just 24 the youngest in American military history.

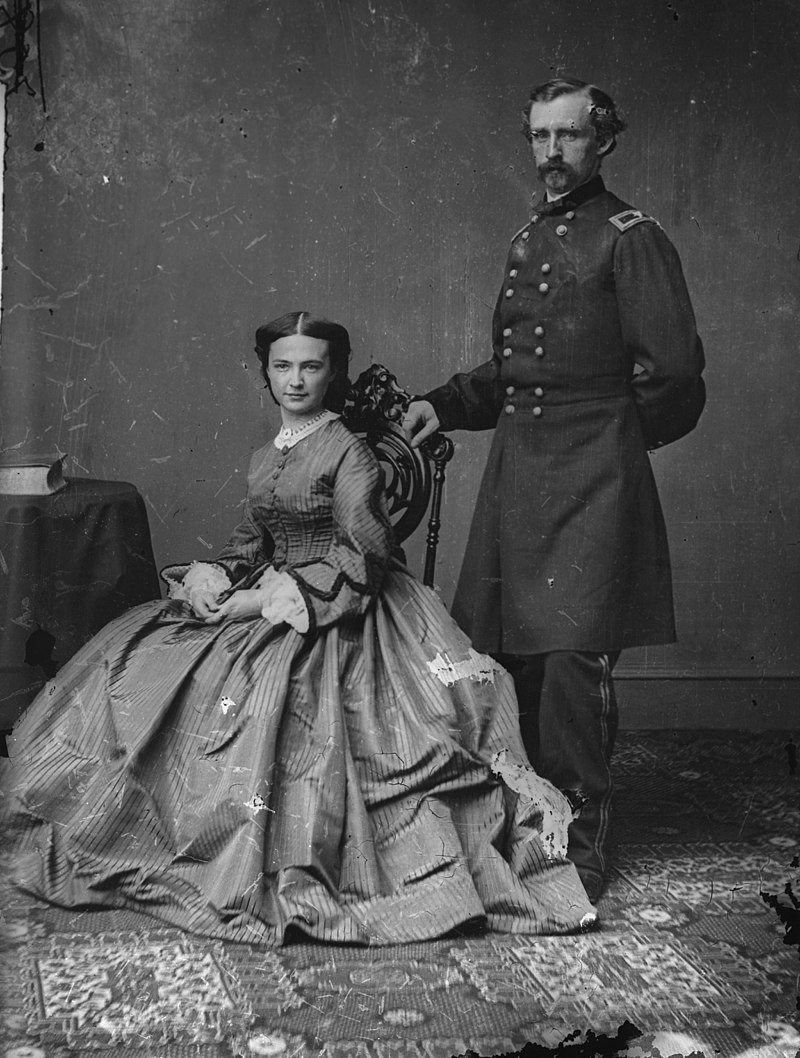

On 9 February 1864, he married Elizabeth ‘Libby’ Bacon, the daughter of a prominent Judge who had at first refused her permission to court Custer until he reached a rank appropriate to his family’s status. But it was a love-match and the Judge finally relented and though Custer often strayed, after all the distractions of being the dashing boy-General must have been great, he remained devoted to Libby for the rest of his life.

Libby, who had insisted upon accompanying her husband on his campaigns was to outlive him by more than half-a-century devoting her time to spreading his fame and securing his reputation. She wrote many books about her life with Custer that became instant bestsellers and was also highly litigious threatening legal action against anyone who dared impugn his legacy. By doing so she hampered serious research into the events at Little Bighorn at a time when many of those involved were still alive.

Despite her long-life Libby never remarried and was to see he husband’s heroic death replayed time and again on both stage and screen. She died in New York City on 4 April 1933, aged 90.

Upon the conclusion of the Civil War Custer was thrashing around looking for things to do. Reduced to his earlier rank of Captain he considered a career in mining, in the railways and not for the last time, in politics but the pull of the army was always too great.

In 1867 he solicited President Andrew Johnson for a Commission in General Winfield Scott Hancock’s forthcoming campaign against the Cheyenne Indians, and it was in this campaign and subsequent Indian Wars that he was to find fame and become a part of American folklore.

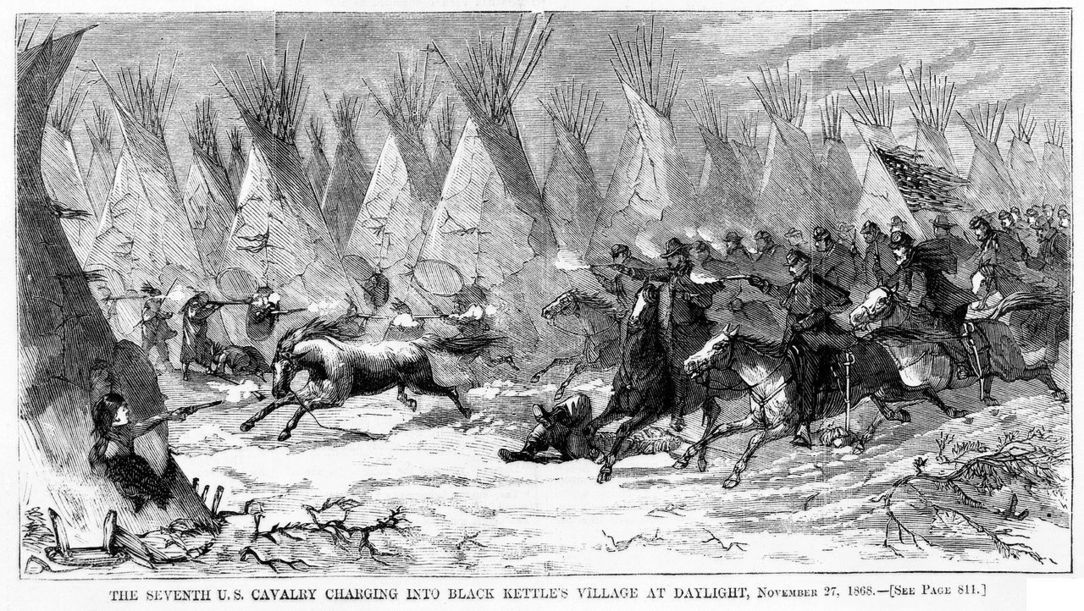

He was promoted and appointed Commander of the recently formed 7th Cavalry and soon assumed the reputation as the great Indian fighter, though most of his battles were in truth little more than skirmishes and one-sided skirmishes at that. His most famous victory came at the Battle of the Washita River on 27 November 1868, when he led his 7th Cavalry in an attack on the camp of the Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle.

There were few warriors in the camp, and it was an easy victory with Black Kettle and his wife being shot in the back as they tried to flee. Unknown to Custer however there were a great many warriors in the hills around the camp and he soon found himself in a perilous position being both surrounded and heavily outnumbered. He now adopted a tactic that would prove significant many years later at the Little Bighorn. He decided to take the women and children hostage.

After looting the camp of anything that might be of value and killing the more than 600 horses and ponies that had belonged to the Indians, he led his troops out of the camp using the women and children as a human shield, seeing this the Indians withdrew and let him pass. He then kept the women and children prisoner until the warrior’s agreed to return to the reservation.

The victory at the Washita River secured Custer’s reputation as the man who the Indians feared more than any other, and he was quick to enhance his fame by claiming that it had been a brutal struggle in which he had killed more than 100 Cheyenne warriors.

The truth was that of the 104 Indians who were killed only 18 could be described as young men of fighting age, most were the elderly, the very young, and women.

But his victory was not without controversy.

A detachment of 21 men under the command of Major Joel Elliott had been cut off and massacred and their bodies horribly mutilated. Custer, who had been less than two miles away, did nothing to come to their assistance. When this was reported some months later to the newspapers he came in for considerable criticism.

Custer was hated by the Indians for his arrogance and his willingness to target women and children, though they respected him as a formidable enemy who did not shrink from combat.

As a man he was unsympathetic and ruthless in pursuit of his ends. He also killed without pity those who did not comply with his demands and to the Plains Indian he was a breaker of oaths and a killer of children. Yellow Hair they believed would pursue them relentlessly until there was not one of them left. His own troops had no great love for him either, they thought him arrogant, self-serving, and brutal but they admired his courage and revelled in the kudos he brought them.

Rumours had been circulating during the Civil War that gold had been discovered in the Black Hills of Dakota and along the Powder River Country of Montana. These were the traditional hunting grounds of the Sioux and Cheyenne Indians who did not take kindly to trespassers, and it was a place that most white men had the common sense enough to avoid.

Despite this the rumours ensured an influx of miners heading along the Bozeman Trail into Montana and towards the town of Virginia City from where they could easily infiltrate Indian land to mine for gold. As a result, tensions rose and attacks upon the miners, though sporadic and ill-organised, became more frequent.

The response of the United States Government to the increasing violence wasn’t to demand the miner’s departure but to build forts the length of the Bozeman Trail to protect them. This outraged the prominent Sioux Indian Chief Red Cloud who believed that the building of the forts made the Indians virtual prisoners in their own land. Unifying the tribes under his command he soon turned their anger into all out resistance.

In a brilliantly fought campaign Red Cloud totally outfoxed the Army Commanders on the ground, forts were besieged, isolated army units attacked, wagon trains harassed, and miners killed.

Red Cloud’s War, as it become known, culminated in the Fetterman Massacre. The worst defeat suffered by the army at the hands of native warriors to that point.

On the 21 December 1866, Captain William Judd Fetterman, who had sometime earlier boasted that he could defeat the entire Sioux Nation with just a single company of troopers, left Fort Kearney with 80 men on a punitive expedition against Indians who had the previous day attacked a detachment out collecting wood.

Just a few miles from the fort he encountered a small band of warriors led by a young War Chief named Crazy Horse. Before fleeing the warriors bared their bottoms to the troopers. Furious at the insult Fetterman gave chase and rode straight into the trap that had been set for him. Surrounded and outnumbered he along with all his Command were killed.

The conflict was to drag on for almost another eighteen months before the U.S Government sued for peace and in the ensuing Treaty of Fort Laramie of November 1868, the Black Hills and the Powder River Country was ceded to the Sioux and Cheyenne Indians. It was to be their land exclusively and no white man was to be permitted to enter. It also established the Great Sioux Reservation. Red Cloud, however, refused to sign until all the forts along the Bozeman Trail had also been dismantled.

Chief Red Cloud’s resistance was to be the only war won by the Native Indian Tribes against the United States Government. But Red Cloud himself recognised that any further resistance would be in vain and that the best way to secure the survival of his people was to adopt the white man’s ways. He was to retire to the Reservation where he spent the rest of his life struggling to improve the living conditions of his people. He died in 1908, a Reservation Indian.

For the next five years an uneasy peace settled upon the territory of the Plains Indians. For them their land was sacred, it was the essence of the Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit or Mystery. The Sacred Entities that were in all things, making the food you ate, the ground you stood upon and the very air you breathed sacred. To trespass upon the sacred land of the Sioux Indian was a violation of everything they held dear and a deep insult that could not go unpunished.

In 1873, Custer was sent to Dakota Territory to protect the railway that was being built across Sioux Indian land. The following year on the pretext that it was a scientific and geographical study he led an expedition into the Black Hills with 1,000 men under his command, 100 wagons, a coterie of reporters, and President Ulysses S, Grant’s son Fred, who spent most of the expedition drunk.

He was venturing into territory never seen by a white man before and the expedition soon became a great media event with Custer as its star turn.

The dashing Colonel had himself photographed upon a horse, conversing with his staff, and posing with the bodies of the grizzly bears he had shot with his favourite Crow Indian scout, Bloody Knife. The expedition was declared a great success and more significantly upon his return he announced that he had found gold. According to the Sioux Indian Chief Black Elk it didn’t matter whether there was gold in the Black Hills or not because he had no right to be there. The Sioux had been told that the land was theirs “as long as the grass should grow and the water flow.” He later said: “I heard that Long Hair had found there much of the yellow metal that sends Waischus (White People) mad. Long Hair had told them about it with a voice that went everywhere. Later we killed him for doing that.”

Within two years of Custer’s announcement more than 25,000 gold prospectors were working within Sioux territory.

Rather than provoke another war the Indians moved farther north to try and avoid the white man’s encroachment, but this was proving increasingly impossible to do and with the Government ignoring their protestations some Indians began to take matters into their own hands and increasing numbers of prospectors were being killed. One of those responsible was, Crazy Horse.

Crazy Horse was a Sioux warrior of immense reputation. As a young man he had spent much of his time in quiet contemplation and has been described by those who knew him as a loner but on the battlefield and as a leader of men he was formidable.

Born sometime in the early 1840’s he had earned his reputation in numerous engagements against the traditional enemies of his people, the Crow, Shoshone, Arikara, and Pawnee. He had also fought against the U.S Cavalry at the Battle of Platte River Bridge Station, led the attack against the Wagon Box which left five soldiers dead and many more wounded, been pivotal in the defeat of Fetterman and his men and had fought alongside Chief Sitting Bull at the Battle of Arrow Creek.

In 1866, he had been made a Shirt Wearer or War Chief. Now he would disappear from the Sioux Camp for weeks on end and whenever he did so white men would end up dead their bodies carefully laid out within a circle of arrows.

In 1876, the U.S Government announced that they wanted the Black Hills and the Powder River Country back and that they expected the Lakota and Hunkpapa Sioux along with the Cheyenne to sign a new treaty ceding the territory to them. Many of the Indian Chiefs initially agreed to do so but Chief Sitting Bull refused saying that: “What Treaty has the white man made that he has ever kept.”

He knew that the White Man’s Government had no respect for his people’s traditions and beliefs and merely wanted the land back so they could get the gold and told their representatives: “You are fools to make yourselves slaves to a piece of fat bacon.”

He would not sign the treaty, would remain in the Black Hills, and invited the other tribes to join him.

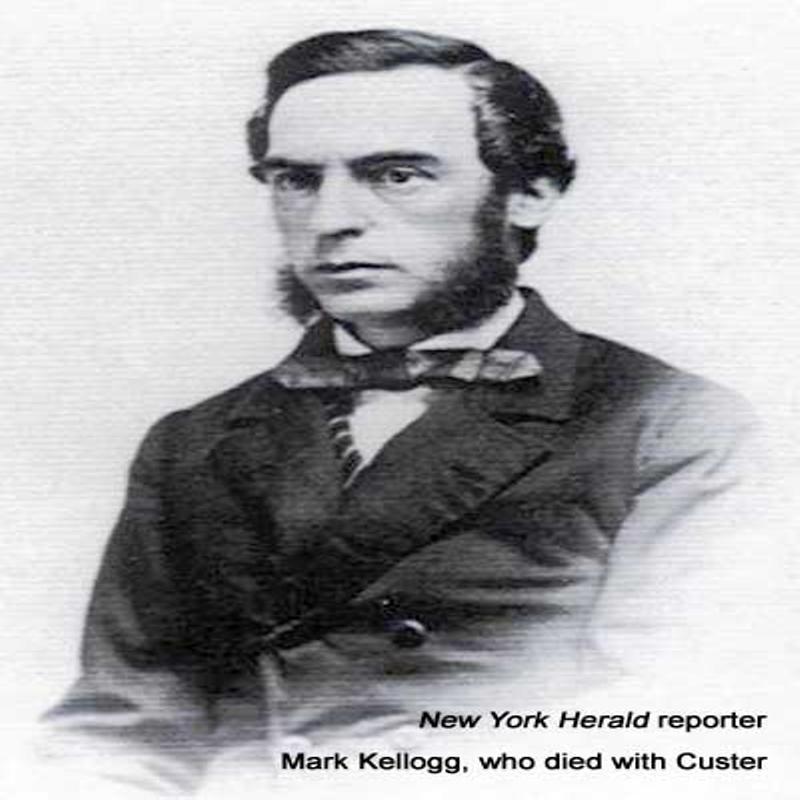

Custer, always the consummate self-publicist invited correspondents of the press to accompany him on all his campaigns and if they failed to praise his endeavours sufficiently, he would supplement their work by writing for the press himself under the pseudonym of Nomad.

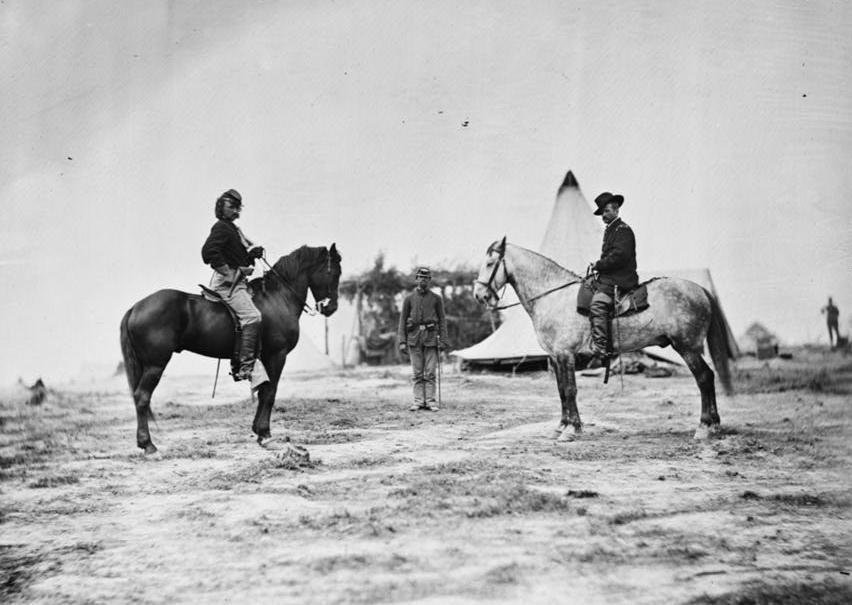

He also dressed to impress wearing a wide-brimmed slouch hat, tight olive coloured corduroy trousers, a black velvet jacket and a sailor’s collar emblazoned with silver stars. His blond hair he wore long in ringlets and scented with cinnamon. Though by the time of his final campaign he’d had his thinning hair cut short and had taken to wearing buckskin.

Custer, who had always had political ambitions, was flattered by all the attention that was being showered upon him by the leading members of the Democratic Party. They may have been grooming him as a future Presidential Candidate and certainly Custer thought so. But he was hampered by a reputation for being less than honest and had the unfortunate habit of bad-mouthing his political opponents in public. He also had a fractious relationship with his superiors.

On 15 March 1876, he was summoned to Washington to testify under oath in the corruption scandal that was engulfing the U.S Secretary of War William W Belknap. During his testimony he was both outspoken and accusatory being particularly scornful of President Grant’s brother Orville, whom he implicated in the corruption.

Custer was political point scoring and seemed to be trying to cement his position as the Democratic challenger to the incumbent Republican President but much of what he said were downright lies. Indeed, his views were so, partisan that his testimony was considered worthless, and he was deemed less than trustworthy. He quickly became the victim of a campaign of vilification in the Republican press.

He had hoped that he would be given command of the major military campaign being planned against the Sioux, but he had been hoist by his own petard and under no circumstances would President Grant countenance any such thing.

He begged for a personal meeting with the President, but this was denied and it took considerable lobbying by his friend and mentor Philip H Sheridan and William Tecumseh Sherman for Custer to be reinstated to the command of his old Unit the 7th Cavalry.

The campaign itself then, would be led not by Custer the great Indian fighter but by General Alfred Terry. Custer, however remarked to an Officer on General Terry’s Staff, Captain William Ludlow that he would cut loose from Terry at the first opportunity he could get. He was determined, he said, to restore his reputation and win the campaign single-handedly if he could.

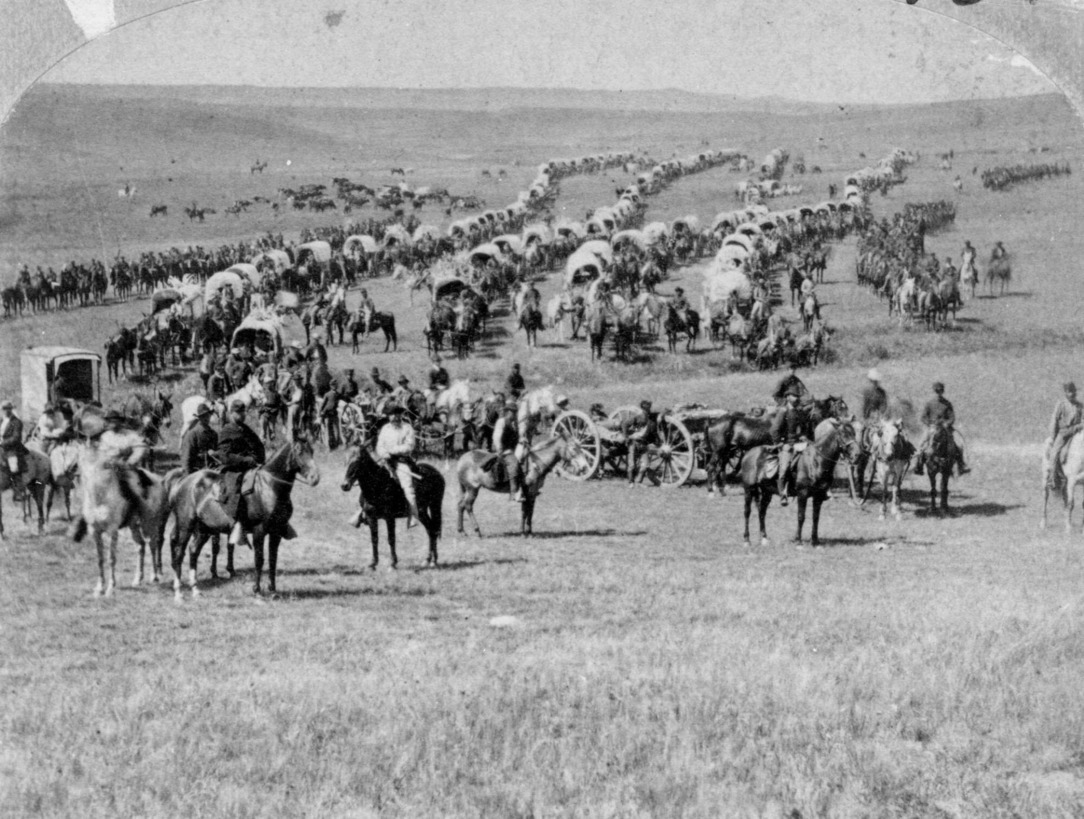

The plan of campaign was for three separate Columns led by General’s Alfred Terry, John Gibbon, and George Crook, some 6,000 men in total, to advance from different directions before converging on the main Sioux encampment at the same time. Custer’s 7th Cavalry were to form the mounted element of the army, to act as reconnaissance and be the first point of contact and so on 17 May 1876, 617 men of the 7th Cavalry departed Fort Abraham Lincoln in North Dakota in the direction of the Black Hills.

Custer, who was seeking a swift victory before the rest of the army arrived had declined to take along any wagons opting instead for a mule train meaning that he left a great many extra supplies behind including several quick firing multi-shot Gatling guns. He also refused the offer of a few infantry companies as reinforcements wanting only mounted troops for speed and mobility.

His troopers themselves were not necessarily the well-trained soldiers of legend. Though he had a few veterans in his unit most of them were recent immigrants from Europe many of whom spoke only a few words of English and had been sent to join the 7th Cavalry in the months immediately preceding the campaign having received only the most rudimentary training in how to ride a horse and fire a weapon. With an average age of 22, some were as young as 16, legally too young to be in the army at all. Custer nevertheless remained confident of victory, so much so that he had arranged to do a speaking tour following the successful conclusion of the campaign.

He had also invited along Mark Kellogg, a reporter for the local newspaper the Bismarck Tribune whose reports were to be reprinted in the New York Herald and who made little effort to disguise his admiration for the subject of his dispatches: “And now a word for the most peculiar genius in the army. The dashing Custer is ready for a hell-whooping fray with the hostile red devils, and woe to the village of scalp-lifters that comes within reach of Custer and his brave companions who would freely follow him into the jaws of hell.”

On 17 June 1876, Sioux and Cheyenne Warriors under the command of Crazy Horse attacked General George Crook’s column of 1,200 men near the Rosebud River in Montana. In a hard fought battle that left 32 of Crook’s advance guard dead and a further 21 seriously wounded a catastrophe was only averted by the courage of Crook’s Crow and Shoshone scouts. Still, in control of the battlefield at the end of the day, Crook was to claim a victory but he not long after withdrew back to his base camp at Goose Creek ensuring that he would be unable to support Custer in any attack upon the Sioux village as had been planned.

It was clear that Crook had been badly shaken by the ferocity of the Indian attack and the Battle of the Rosebud River and the withdrawal of Crook’s Column had in fact been a great and vital strategic success for Crazy Horse.

In the months preceding the campaign to force him back onto the Reservation, Sitting Bull, the admired warrior now turned respected Holy Man, had been trying to form a united front among the Indians Tribes to oppose the white aggressor. In this he had been largely successful gathering together a great many Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors.

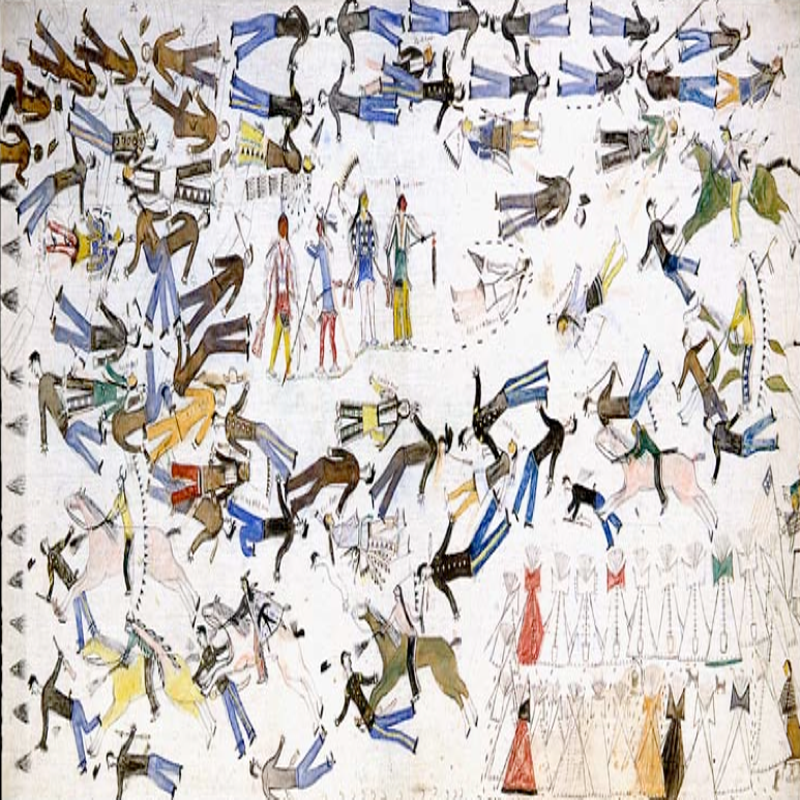

In the days before the Battle of the Little Bighorn or The Greasy Grass, as it is known by the Sioux, the tribes held a Sun Dance, an exclusively male affair that was an ancient and sacred ritual, a summoning of the spirits of their ancestors to seek a vision of what was to come.

Sitting Bull, painted in ceremonial yellow had a piece of flesh cut from his arm followed by more and more until he was covered in blood. He then danced for two whole days accompanied by the other Chiefs until at last he went into a trance. After many hours he awoke to announce what he had seen, and drew a picture of many dead white soldiers:

“The whites had wanted war and we will give it to them. The Indians will have a great and bloody victory.”

Sitting Bull had received many visions in the past and had never been wrong and the Indians took great heart from his words. But he also warned them not to take anything from these dead soldiers for to do so would bring great hardship upon them. Custer, in the meantime, pushed his men ever harder in pursuit of their goal.

By riding through the night and not pausing to eat they reached their destination in the Little Bighorn Valley around mid-morning on 25 June 1876. His men were exhausted but even now he didn’t relent. Scouts were sent ahead to find the main Sioux encampment whilst he rode on determined to ensure that no Indian should have the opportunity to escape the 7th Cavalry.

Around 2.30 in the afternoon his Crow Indian scouts reported they had found the Sioux encampment and that it was the biggest they had ever seen. Custer advanced to the top of a nearby ridge to see for himself. They were not exaggerating, the Sioux village stretched for miles along the banks of the Little Bighorn River.

One of Custer’s Crow Indian scouts, Man Runs In, said later that upon seeing the camp Custer “Went white, even whiter than usual,” and that he had never seen him like that before. He said to Custer: “We are all going to die this day.”

The Indian scouts began to strip off their clothing and chant their war songs in preparation for battle.

Custer’s Chief Scout, the half-Indian Mitch Bouyer aware of the fate that would befall them if they fell into the hands of the Sioux dismissed them from further service and ordered them to leave. He had earlier discovered the evidence of the Sun Dance and he knew that the Sioux, Cheyenne, and others were going to fight this day.

It has been estimated that there were at least 10,000 Indians in the Sioux village with perhaps as many as 3,000 of them warriors.

Custer however, had seen only women and children carrying out their daily chores. It was possible that the young braves were away on a buffalo hunt, they had after all seen many buffalo carcasses on their ride to the Little Bighorn Valley. If this was the case then it provided him with the perfect opportunity to achieve a swift victory, and without having to do any serious fighting at all. He would do just as he had done eight years earlier at the Washita and take the women and children hostage. He turned to his men and shouted:

“Hurrah boys, we’ve got them! We’ll soon finish them off and return to our station.”

His words were greeted with a chorus of cheers.

Custer had some 617 men under his command, around 100 of whom were guarding the slow-moving mule train to the rear of his column. The rest of his forces he now fatefully decided to divide up into three columns without fully knowing the strength of his enemy. This was something that even the most basic military manual warned against doing.

He first ordered Major Marcus Reno, an Officer whose liking for the of the bottle often clouded his judgement to take 175 men and attack the Sioux village from the north. Custer would support him with an attack from the east. He then ordered Captain Frederick Benteen to take around 120 men and scout the hills to the west while also preventing any Indians from escaping south.

Benteen challenged the logic of the order, surely, he would need every man he had available for the attack? Custer would not have his orders questioned and certainly not by Benteen.

They had a barely disguised loathing of one another and to say their relationship was a fractious one would be to understate it. More than once they had almost come to blows, and it had been Benteen who had leaked to the press the fate of Major Elliott and his troops at the Battle of the Washita. As a result, Custer did not trust Benteen who in turn thought Custer a vainglorious self-publicist heedless of the lives of his men.

It seems possible now that Custer ordered Benteen on a seemingly pointless scouting mission merely to prevent him from being able to share in the glory that he felt sure would accrue from his forthcoming victory – whatever the reason it was to prove a fatal error.

A little after 3 o’clock Major Reno crossed the Little Bighorn River and began his assault on the Indian village but very quickly had a loss of nerve and instead of charging it as expected he stopped short of the village itself and ordered his troops to dismount and form a skirmish line from where they kept up a sustained but indiscriminate fire.

Unknown to Reno and indeed to Custer himself there were a great many warriors in the village who had been sleeping in late. Among them was Crazy Horse, and as the women and children fled along the riverbank and away from the fighting, he began to rally the warriors.

At the same time old men were shouting, “White soldiers attack us young men go and fight them.” Many did just that and hundreds now began to file out of the village led by Crazy Horse his words, “It is a good day to die,” echoing in their ears.

As more and more Indians began attacking Reno’s force, he quickly became aware that he was heavily outnumbered and in danger of being outflanked. He now ordered a retreat across the Little Bighorn River and to the shelter afforded by the woods and timber on the other side. But as the number of Indians attacking them continued to multiply – as if they were emerging from the very ground itself – panic began to set in.

The Crow Indian Scout Bloody Knife who had been fighting alongside Major Reno and upon whom he had become increasingly reliant was shot through the head his blood and brains splattering the side of Reno’s face. Panicking, he now lost all control of the situation ordering his men to mount and retreat to a nearby hill, then to dismount, and then to mount again. Eventually he shouted that anyone who wished to survive should follow him.

What had been a retreat now turned into a rout as soldiers desperately scrambled for the relative safety of the hill as the Indians swarmed among them and many soldiers were shot or dragged from their horses and hacked to death. Some had not heard the order at all and were left behind in the timber to fend for themselves.

Whilst Reno was engaged in the fight of his life and with his command close to collapse, Custer who should have been supporting him had been distracted by an Indian decoy he now gave chase to. He failed to catch them, but the chase had taken him to a position where he could now see the Indian women and children fleeing west along the riverbank.

He ordered Captain Myles Keogh to take 120 men and form a protective left flank on nearby Calhoun Hill whilst he would pursue the women and children and take them prisoner.

Custer trailed the fleeing women and children down Medicine Ridge Coulee on the other side of the river while 40 men of the so-called Grey Horse Company tried to find a place to ford it.

At this point Custer was still confident of victory but the men he had sent to find a place to cross the river could not do so. The Indians, however, knew exactly where to ford the river and now began to do so in their hundreds. At last realising what he was up against Custer scribbled a hasty note: “Benteen, big village, be quick, bring pacs. P.S Bring pacs.” He handed the note to the bugler Giovanni Martini telling him to take it to Benteen, and quickly.

Captain Benteen was less than five miles from Custer’s position when he received the note and could have been there in twenty minutes at the gallop; but he showed little urgency and insisted that he could not bring any ammunition packs until the mule train arrived.

Ignoring his orders, he instead moved to support Major Reno who remained under attack on the hill where he had now taken up a defensive position. Meanwhile, on Calhoun Hill Captain Keogh’s troops rested in the hot June sun their rifles on their laps unaware that Indians on foot concealing themselves behind the bluffs and in the undergrowth were rapidly advancing towards them.

Custer had by now been forced to curtail his pursuit of the women and children by the sheer number of Indians who were attacking him. He also appeared confused by the topography withdrawing towards an exposed position that has since become known as Last Stand Hill. He was losing control of the battlefield.

One of the first men to die on the retreat to Last Stand Hill was Mark Kellogg. He had been unable to get his horse to move until finally it turned and started to trot towards the pursuing Indians. His last dispatch had been sent four days earlier, it read:

“By the time this reaches you we would have met and fought the red devils with what result remains to be seen. I go with Custer and will be there at the death.”

His notebook was found beside his dead and mutilated body. He is believed to be the first War Correspondent to die on active service.

In the meantime, those Indians who had been stalking Captain Keogh’s troops on Calhoun Hill emerged from their hiding places and began to rapidly advance upon his position. Keogh hastily ordered the formation of a skirmish line. The inadequacy of his trooper’s weaponry quickly became apparent, however.

They were armed with single shot Springfield Rifles, a powerful, accurate weapon effective at almost 700 yards but they were not fighting at such distances and many of the Indians had purchased Winchester and Henry repeating rifles from the Reservation which though only effective from 200 yards or less could fire 13 rounds every thirty seconds to the troopers 4 at most. Once the Indians got within range the troopers found themselves heavily outgunned. Also, their fire power was diminished by 25% because of the need for horse-holders with one in every four men being assigned to this role.

The Indians were swarming down a nearby ridge and the bluffs on either side of Keogh’s position and he was not just taking heavy casualties but was in danger of being outflanked. In an attempt to reverse the situation, he led 40 mounted men in desperate charge to try and disperse those Indians attacking his front. The charge was repulsed and as the fleeing cavalrymen returned to their own lines panic began to set in. The Indians were close now and the combat was becoming personal and hand-to-hand. Worse was to follow as most of the remaining horses were scared away by Indian women waving blankets. The few who were still mounted now began to ride towards Custer’s position on Last Stand Hill.

The skirmish line broke as those on foot also began to run towards Custer. Captain Keogh who was trying to maintain some semblance of order was knocked from his horse and killed and the retreat soon became a rout as those troops still alive now fled for their lives.

Indians present were later to describe the scene: “The troopers were beside themselves, they were firing wildly into the air, some threw up their hands and tried to surrender, others feigned death.”

It was a massacre and only around 20 of Keogh’s men made it to Last Stand Hill.

While Custer and his men were fighting for their lives, Captain Benteen had joined Major Reno’s beleaguered force where they could hear the firing in the distance but did nothing. When some of the Officers present suggested that they ride towards the sound of the guns, Major Reno insisted that he first had to find his good friend Minnie Hodgson. He was to absent himself for thirty minutes looking for Lieutenant Hodgson’s body. When those same Officers approached Captain Benteen, he told them that it was not his command and there was nothing he could do. Finally, Captain Weir frustrated by their inaction disobeyed orders and led his company in the direction of the fighting.

Custer was on Last Stand Hill with around 70 men and just like Keogh before him most of his horses had been scared off. He would have to remain where he was, and bugle calls could be heard and orders shouted as a desperate reorganisation was attempted.

By this time Crazy Horse had broken off his attack on Reno to join the fray around Last Stand Hill. He had already cut-off any possibility of Custer retreating south and now he was everywhere exhorting his braves to ever greater efforts and warriors speak of him single-handedly charging a line of troopers.

Custer now ordered that the few remaining horses be shot to create a defensive buffer, but they afforded little cover to the rain of bullets and arrows that were showering down upon them. The shooting of the horses also created panic however, and 9 mounted men now fled towards a place called Deep Ravine in a desperate attempt to escape the fighting to be quickly followed by 28 men on foot. Custer could do nothing to prevent them from fleeing and it is likely it was around this time he was killed for not long after the rest of his command began to fall apart and Indians later described a man in buckskin crawling on all fours, blood pouring from a wound to the chest.

The Sioux Indian Chief Gall now led his braves on a frontal assault against those few troopers still resisting and within moments it was all over. None, of those who had fled Last Stand Hill escaped the battlefield, though one man very nearly survived.

Sergeant Foley had taken flight much earlier in the fighting and his horse appeared to be outrunning the Indians who were pursuing him. Indeed, they were later to say that they had effectively given up the chase. Foley obviously didn’t think so for he suddenly pulled up and shot himself through the head. The Indians, who were superstitious regarding suicide, left his body unmolested.

Captain Weir arrived on a ridge overlooking the battlefield at around 5.20 pm. The fighting appeared to have ceased except for the occasional gunshot and the whooping of the many Indians who were still present. A little later he was joined by Reno and Benteen but fearing an Indian attack, they didn’t remain long and returned to their defensive position on what is now known as Reno Hill. There they continued to be assailed by the Indians and were subject to sniper fire throughout the rest of the night.

The following morning learning of the approach of General Terry’s Column from the north the Indians withdrew. That afternoon Major Reno and Captain Benteen returned to the site of the previous days fighting to be greeted by a horrific sight.

The Little Bighorn Valley was littered with the bodies of dead troopers. They had been stripped naked and horribly mutilated. Some had their eyes gouged out, others their tongues removed, ears severed, and genitals cut off. Hands and feet were missing, sticks had been rammed down throats, and all had been scalped; the fact that most had also had their faces smashed in by the many squaws who accompanied the warriors and were tasked with finishing off the badly wounded troopers. The state of decomposition in the hot June sun also meant that identification for the most part was almost impossible. Indeed, only 56 were positively identified either from birthmarks, tattoos, or from personal items left lying nearby.

Still fearing that the Indians might return the bodies were hastily buried where they lay, and the Little Bighorn battlefield is unique in this respect. The Indians had already removed their dead.

The mutilations had been committed not just for reasons of bloodlust but because the Indians believed that to do so would impair their enemies in the afterlife. As far as White America was concerned the desecration of the bodies extended to the looting of personal items such as wedding rings, religious icons, and family mementoes. The behaviour of the Indians in the immediate aftermath of the battle was considered an outrage and convinced them that they were dealing with little more than heathen savages who needed not to be civilised but exterminated, just as Sitting Bull had warned they would.

It is now thought that perhaps as many as 231 men died with Custer at the Little Bighorn and that all the bodies have not yet been recovered. A further 58 were killed and 55 wounded, 5 later dying of injuries sustained in the fighting from Major Reno’s command.

Among those killed with Custer were his brothers Tom and Boston (Boston had in fact rushed from the slow-moving mule train at the rear of the Column upon hearing the first shots fired to be with his brother) his cousin Henry Armstrong Reed and his brother-in-law James Calhoun.

The only living thing found on the battlefield was Major Myles Keogh’s horse ironically named, Camanche. It was to be buried upon its death many years later with full military honours.

Indian casualties remain unknown but the oral evidence of those warriors who were present suggest between 60 and 120 with Sitting Bull himself indicating that it was nearer the former.

The American people had of course got used to learning of much higher casualty figures in the recently fought Civil War between the States but nevertheless the impact of Custer’s defeat was so great that it became almost a national trauma. The thought that a modern army could be defeated by Native American Indians in a set-piece battle simply wasn’t credible. Rumours began to circulate that Sitting Bull wasn’t an Indian at all but a renegade white man who had been trained at West Point, but the focus soon shifted to finding someone to blame.

An investigation into the events surrounding the Battle of the Little Bighorn found that Custer had exceeded orders and acted hastily in going onto the attack before adequate support had arrived. Blame for the defeat however was initially directed at Captain Benteen with the antipathy between him and his Commanding Officer a topic of much debate. Had he deliberately refused to come to Custer’s aid because of the hatred he had for the man?

In a later Court of Inquiry, he declared that to have obeyed Custer’s order was impossible because to have done so would have been suicide. Benteen, who had often expressed his sympathy for the plight of the American Indian and was to go onto say: “We were at their hearth and home, their medicine was working, and they were fighting for all the good God gives anyone to fight for.”

He was initially found guilty of disobeying orders though he was to be cleared of the charge upon appeal. Most of the blame for the defeat was to fall on Major Reno, at least as far as public opinion was concerned. He was widely reported to have been drunk at crucial times during the campaign and to have displayed cowardice during the battle itself. Believing that he had been made a scapegoat for the disaster he demanded a Court of Inquiry to clear his name which was held in Chicago in November 1879.

It cleared him of responsibility for the disaster, but it was plain that during the battle he had been ineffective, lost control of his command, and that the survival of his troops had been largely down to the courage and leadership displayed by Captain Benteen. Many of those who testified on his behalf were later to say that they had been coerced into doing so.

Captain Frederick Benteen was to continue his career in the army being promoted to Major but in 1887 he was dismissed from the service for being drunk whilst on duty. This was later reduced to a year’s suspension. Retiring for reasons of ill-health he died in Atlanta, Georgia, on 22 June 1898, of heart disease.

Major Marcus Reno’s drinking got progressively worse in the years following the events at the Little Bighorn and just a year after his acquittal at the Court of Inquiry he was again court-martialled for drunk and lewd behaviour unbecoming an Officer. Found guilty he too was dismissed from the service. Plunged into poverty, so much so that he could not even afford the train fare to attend his own son’s wedding, he tried to sell his memoirs but was unable to find a publisher. He died in Washington on 29 March 1889, aged 54.

When in 1926 a proposal was made to build a memorial to Major Reno on the site of the battlefield, Custer’s widow, Libby, objected, there should be no memorial, she said, to the only coward in the regiment.

The Little Bighorn was never truly Custer’s Last Stand but that of Sitting Bull and the Northern Plains Indians.

The United States Government was now determined to resolve the Indian problem once and for all. They would either be forced onto the Reservation or be eliminated altogether, and a massive army equipped with the latest repeating rifles, Gatling guns and artillery were dispatched West for that very purpose. The Indians had little option but to flee.

The always fragile unity of the tribes soon broke down and Sitting Bull with his Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux people were forced to flee north eventually crossing over the border into Canada, but they were no more welcomed or accepted in Canada than elsewhere. They longed to return home even if it was into what they considered little better than captivity.

On 19 July 1881, Sitting Bull, having taken his people back into the United States surrendered himself to the Authorities promising to remain on the Reservation. Instead, he was to become a celebrity touring for four months with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show that would always culminate in a dramatic re-enactment of Custer’s Last Stand. Though Sitting Bull’s role was small it was the star turn.

He was paid $50 a week for riding a horse once around the arena to the applause of the audience whom it was said he cursed in his native tongue as he did so. His short stage career made him a wealthy man, posing for photographs and selling his autograph – though much of the money he later gave away to beggars and the homeless. Following his retirement, he returned to the Reservation.

Sitting Bull remained an honoured and highly respected Medicine Man and Chief to his people, so much so that the Authorities continued to fear his influence and the power of his name.

On 15 December 1890 fearing that he was about to join the resurgent Ghost Dance Movement that would end so tragically at the Massacre of Wounded Knee, the Authorities set out to place him under arrest. When Sitting Bull refused to go quietly and objected to being manhandled those Sioux present, outraged at his treatment, opened fire on the arresting officers. In the ensuing fire fight 8 Policemen and 7 Sioux were killed, including Sitting Bull, shot in the back of the head by Red Tomahawk, a Sioux Indian Policeman.

Crazy Horse tried to remain on the plains, but he and his people were mercilessly pursued by the U.S Army. His last significant engagement with the army came at Wolf Mountain, Montana, in the late winter of 1877 but with his people starving he had little choice but to yield to the inevitable. He surrendered to the Red Cloud Agency near Fort Robinson in Nebraska.

Crazy Horse never reconciled himself to life on the Reservation and rumours persisted throughout his four months there that he was about to lead his people back out onto the plains. Finally, orders were issued to take him into custody and on 5 September he was escorted to the Guardhouse. There, struggling with his guards he managed to escape outside only to be stabbed in the back with a bayonet. He died later that same night.

His body was then handed over to his elderly parents who had it buried in secret and the whereabouts of his burial place remain a secret to this day.

There is also no surviving image of Crazy Horse as he refused to have his photograph taken believing that the camera would steal his soul.

A memorial to the dead of the 7th Cavalry now sits on Last Stand Hill. A similar memorial is planned for those Native Americans who also died.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, War

Share this post: