Darien Expedition

Posted on 12th June 2021

In the 1690’s an economic slump followed by four consecutive failed harvests led to widespread famine in Scotland with farms abandoned, the land depopulated, and the towns and cities becoming choked with the destitute and starving. Following on from decades of war and civil strife the ‘Ill Years’ as they were known had not only decimated agriculture but left what remained of Scottish commerce unable to compete with its more powerful English neighbour and doubts were being expressed that Scotland could survive at all as an independent nation. But one man thought he had a solution to the nation’s problems.

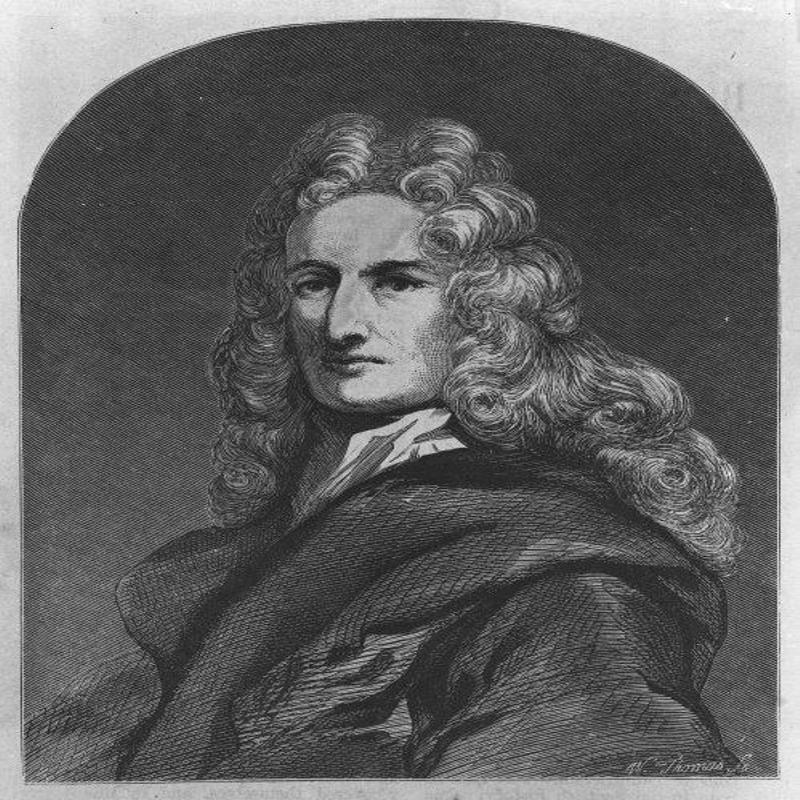

William Paterson was born in April 1658, in the village of Tinwald in Dumfries and Galloway but though he was Scottish by both birth and parentage he had mostly been raised in England and knew little of his homeland making his fortune as a young man in the Bahamas dealing in the in the trans-Atlantic commodities trade only returning to England in 1694, a very rich man; the same year he helped found the Bank of England created to service the growing national debt, and it was also in London that he came up with the scheme he claimed would make Scotland not only rich again but restore its pride and national prestige.

Trade with the Pacific markets could be extremely lucrative, but it could also be ruinously expensive as all merchant ships had to make the long and hazardous journey around Cape Horn on the southernmost tip of South America and many were lost along with their valuable cargoes as a result. Needless to say, the cost of insurance was punitive and the distance that had to be traversed added months to the journey.

Paterson envisaged a Scottish colony at Darien on the Isthmus of Panama where goods loaded on the Pacific shoreline could be ferried the 40 miles overland to the Atlantic coast where they could be reloaded onto waiting ships, a service for which the Scots would charge a not insignificant commission.

The Darien Venture, as imagined by Paterson seemed genius in its simplicity but he had done little in the way of research and his only real source of information regarding Darien as a location was a ship’s surgeon named Lionel Wafer who had assured him that he knew the area well. It was a paradise he explained to an excited Paterson, it had a sheltered bay, the climate was mild, the land fertile, the rivers clean while the natives were vain, harmless, and welcoming.

Paterson took Wafer at his word, and even though he may not have known much about Darien he could find it on a map, and it seemed ideal. The fact that it had already been claimed by the Spanish didn’t seem to occur to anyone.

Paterson at first tried to raise the money for his scheme in Germany and on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange but the English who had got wind of the scheme and were vehemently opposed to it brought pressure to bear forcing potential investors to withdraw their support. They would always oppose any scheme that threatened their own trade links with the Americas and the Far-East.

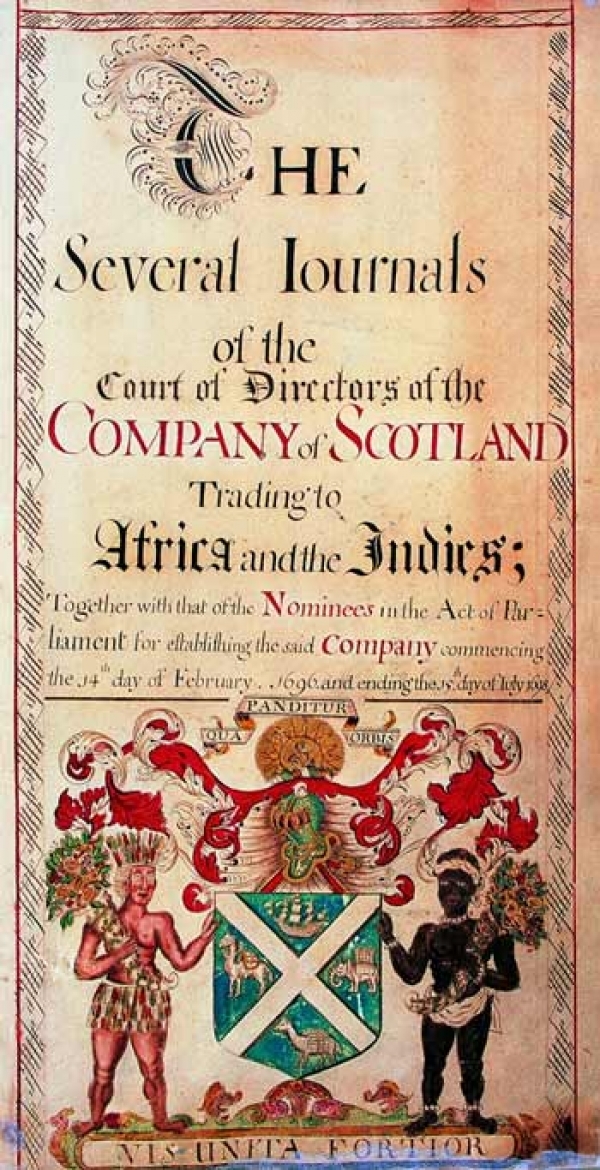

Thwarted in his ambitions by English interference, Paterson relocated to Edinburgh where he badgered and bullied the Scottish Parliament into endorsing his scheme and their support helped greatly in raising the profile of his newly formed Company of Scotland and the scheme fired the imagination of the Scottish people.

Soon it was being described as the last best hope for Scotland as people rushed to subscribe and in just six months more than £400,000 was raised, or 25% of Scotland’s total liquid assets. Indeed, so enthused were the Scots by the talk of this idyllic paradise that was a cash-cow waiting to be milked that some invested their entire life savings, others mortgaged their farms to do so.

Paterson, who was by now close to penury himself having squandered his fortune on various other schemes, was provided with £25,000 with which to purchase supplies and fit out five ships for the voyage. The excitement in Scotland was palpable and the 1200 colonists chosen to make the initial voyage were considered to be the luckiest people alive.

But the ship’s manifest for the journey told its own story: it included a sizeable number of combs to placate the vanity of the natives, Bibles with which to convert them and powdered periwigs for those inevitable social occasions that would become a feature of life in idyllic Darien - it suggests they did not really know what they were letting themselves in for.

The Darien Fleet set sail from Leith on 4 July 1698.

The English had attempted to blockade the harbour and the ships initially became dispersed in the dense sea-mist that had been used to shield them from the prying eyes of the English warships awaiting their departure.

Only Paterson and Captain Robert Pennecuik knew their exact destination, the passengers had been provided with letters revealing the precise location of the colony but with orders that they were only to be opened once they were at sea.

The Fleet did not arrive at Darien until 2 November and during the arduous four month voyage some 70 passengers and crew had died, with many more were sick. Nevertheless, upon their arrival the survivors enthusiastically went about building a settlement on the Isthmus which they now named New Caledonia, but they were not building upon the rich fertile soil they had been expecting but instead upon a boggy morass. Indeed, it was little better than a malaria infested swamp that was not only unfit for cultivation but barely firm enough underfoot to build a mud hut on.

The Native Indians as it turned out were neither friendly nor vain and were not interested in their combs or any other worthless trinkets that the colonists had to offer them. The Spanish were also none too pleased at what they saw as an unscrupulous land grab and their hostile attitude forced the colonists to withdraw behind a hastily constructed stockade, they named Fort St Andrew.

By March of the following year torrential rain and high winds had destroyed many of their makeshift shelters and more than 200 of the colonists had died of exposure and disease while those ships that had been sent out to trade returned empty-handed.

The colonists unable to bargain for goods with the Spanish had become reliant upon the English colonies nearby for support but orders were soon received from London that forbade them from trading with the Scots and the colonists were soon reduced to a diet of fish, mouldy bread and boiled flour that they could make into a thin gruel invariably infested with maggots.

They were also forced to work tirelessly sometimes as many sixteen hours a day in intense heat simply to maintain the settlement. It was too much and sick, weak and malnourished they were dying at a rate of ten a day.

Paterson and the other leaders of the expedition who lived separately from the other colonists and recoiled from manual labour causing much resentment tempered their anguish with ample supplies of wine and rum as they argued over the best possible course of action – should they stay, or should they go? If they remained, they may all die, if they returned it would be to penury and public humiliation - neither prospect was an attractive one.

As it turned out the decision was made for them.

Learning that the Spanish were planning an all-out assault on the settlement, they had little choice but to flee and the four ships that returned to Scotland in haste had just 300 survivors aboard. One of these was William Paterson, though he had left his wife dead in the swamps of New Caledonia. But as the first expedition was returning a second had already set sail.

They had departed in August 1699, with 1,302 excited future colonists who had no idea what had happened to the original settlers and were shocked upon their arrival to find nothing but hundreds of unmarked graves. Nevertheless, they remained determined to make the best of a bad situation.

Alas, it wasn’t long before disease again began to take its toll and they were soon dying at the same rate as before but this time when the Spanish attacked, they did not flee but resisted, and did so successfully for many months even at one point inflicting a serious defeat upon the Spanish. But the outcome was never in doubt and besieged by the Spanish in Fort St Andrew they were finally forced to surrender in March 1700 - the Darien venture was over, and it had proved to be a disaster.

The nightmare that had been Darien traumatised Scotland, a country which was already reeling financially, and it was a body blow from which few felt it would ever recover. Those who had participated in the Expedition and survived were now ostracised by their own communities for being the people who were responsible for bringing a once proud nation to its knees.

They now tried to deflect blame for its failure onto the English who they claimed had deliberately sabotaged an opportunity for Scotland to prosper and this resentment was to spill over into violence with several English sailors in Scottish ports being lynched.

The bitterness felt towards the English also helped to fuel a rise in Jacobitism and a longing on the part of many for a return of the Stuart Monarchy. The Government in England also feared a return of a Stuart Monarchy north of the border and now began to press the weakened and vulnerable Scots into agreeing to political union.

The Government in Westminster promised to compensate the Scots for the exact amount that had been lost in the Darien disaster. They also offered to reduce the tariffs on their goods, promised to provide opportunities for them to trade in English markets abroad and made it clear that in future Scotland’s debt would be Britain’s debt. If they refused, however, the border between the two countries would be closed and a trade embargo would be enforced.

One of the prime movers for a political union between the two countries was William Paterson who now argued vehemently that without political union Scotland was doomed to become a primitive, poverty stricken agricultural backwater economically subservient to its more powerful English neighbour.

The dispute within Scotland was bitter and prolonged but nevertheless Commissions were established in both countries to negotiate terms. The members of the two Commissions never met face-to-face but worked through intermediaries.

It took two weeks of often heated debate to force the issue through the Scottish Parliament during which there were riots in many towns opposed to any Union with England.

In attendance throughout the debate was the author and spy Daniel Defoe who reported back to his masters that there was barely one in a hundred Scots in favour of this Union. Even so, when the vote came it was overwhelmingly in favour of signing away Scottish independence with 106 for and only 69 against. On 1 May 1707, the Act of Union was signed.

England and Scotland, who had previously been united under one Crown, would now, along with Wales and later Ireland be a part of a single unitary State – Great Britain. A short time later £398,000, the exact amount that had been lost in the Darien Expedition was deposited into the Scottish Treasury.

Many Scots were unable to reconcile themselves to their loss of independence and felt that they had been ridden rough-shod over by the money men, the rapacious men of commerce, those Lowland Scots who looked south rather than north.

The poet Robert Burns was one of those who lamented what had been done:

“We were bought and sold for English gold.

Never were there such rogues in a nation.”

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: