Death in Europe in Past Centuries

Posted on 30th November 2021

How have attitudes changed towards death in Europe down the centuries? They most certainly have but any attempt to answer this question requires the need to differentiate between familiarity and resignation.

Certainly, the inhabitants of early modern Europe would have had a familiarity with death far beyond our own for it was not only commonplace among old and young alike but highly visible. The rigours of poverty, pestilence, famine and war, the lack of hygiene and high infant mortality rates unimaginable today made death an almost everyday occurrence for the living.

It might then be fair to assume that there was an acceptance of death but if so, it is not indicated by the reaction to death being any less painful or traumatic on those who had lost a loved one. But death was viewed not so much as the tragic end of an individual life but understood more as part of the collective destiny of the species, that death was a part of the natural order as in ‘et morie mur’ or – we shall all die. As such, death could often be treated dispassionately and not necessarily as a time for tears but for ritual, a ritual that would often be organised by the dying person themselves.

A strict routine would be followed both Christian and traditional and it was considered important to be amply forewarned of one’s impending doom so that the appropriate arrangements could be made. The prospect of a sudden death was always greatly feared.

The individual’s progression towards death would be a public occasion with relatives, friends and sometimes even neighbours present at the bedside to witness the dying persons last moments. Any children would also be present, and it was not until the eighteenth century that it was thought right and proper to shield children from the sight of death.

It would appear from the often-complicated funerary rites that death was the cause of little emotional trauma or heartache. This was not so but it was a controlled and restrained grief. Death was always close at hand, so the dying was a time for prayer, religious devotion, and a belief in God and the afterlife. In death the prevailing thought remained how the dying had lived their life and would be considered on the Day of judgement.

Familiarity with death was reflected in the disposal of the corpse and the attitude of the Church towards human remains. It was felt that so long as the corpse was interred within the confines of a Church, or buried in consecrated ground, then how it was then disposed of wasn’t important. Thus, Charnel Houses where the bodies of the dead were piled up and the bones and skulls often used for decoration and adornment became common.

Indeed, at this time the living and the dead co-existed in a manner that we would now consider disrespectful with Churchyards often used as places of public recreation and commercial activity. In the thirteenth century the dying believed trusting their remains to the care of the Church alone was enough to ensure they would simply be at rest until the time of the Second Coming of Christ.

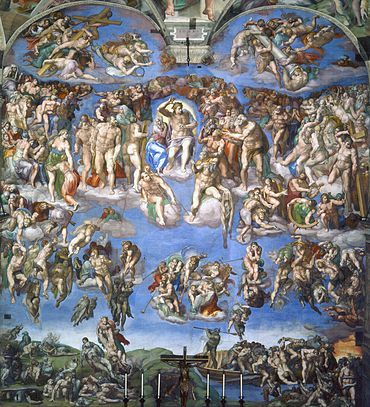

By the beginning of the fourteenth century this had been largely displaced by a belief in the Last Judgement. This was to burden the dying with the responsibility for securing their passage to heaven, and the fear of death itself was supplanted by extreme anxiety over what might follow. So, in its application death remained a collective rite but the idea of the Last Judgement had now made it peculiar to each individual and ritual alone would no longer suffice to ensure the eternal repose of the soul. God would bear witness to the merits or otherwise of the stricken at their moment of death.

By the middle of the fourteenth century the Day of Judgement had become more vivid and fearful in the form of the Final Test whereby the dying would endure visitations by little demons and evil spirits known as the incubi and the sucubi which invisible to others would tempt the dying to abandon God and embrace Satan. A vigorous spiritual struggle would now ensue, imagined or otherwise, and the ritual solemnity of the deathbed had assumed a greater emotional burden.

The increased individualisation of death had altered irrevocably the commonality of long-held religious assumptions. These assumptions were thrown into even greater confusion by the onset of the Reformation where even the notion of the ‘Good Death’, that is a virtuous life redeemed, no longer remained valid.

For example, Calvinism with its belief in predestination and the notion that the individual by his actions could not influence who God decided to save undermined the belief in a general resurrection and denied the possibility of a period in purgatory for those as yet unredeemed before eventual salvation.

After all, Martin Luther, the father of Protestantism’s original argument with the Catholic Church centred upon his opposition to the sale of indulgencies and remittance of sin after death. The very idea that salvation could be bought and sold was irreligious in the extreme and he doubted the jurisdiction of the Church to interfere in matters that could only be determined by God, and it certainly did not correspond with his idea of Justification by Faith Alone. According to the new Protestant faith God alone was the saviour and the individual, including members of the clergy, played no part in salvation collectively or otherwise.

These new religious controversies along with the changes in society that resulted from them went well beyond the boundaries of theological dispute and only added to the anxieties and uncertainty of the dying.

Following the scourge of plague, the ‘Black Death’ that descended upon the European Continent in 1347, we begin to see the emergence of the horror of death and the overt depictions in popular culture of illness, decay, decrepit old age, death, and decomposition.

For example, the Danse Macabre first enacted by the victims of plague and famine and those destined to endure a slow, ugly, and lingering death. Its vivid illustrations of the decomposition of the body, its skeletal figures and sepulchral images for the first time indicate a resignation to one’s eventual demise, that death was inevitable for all men whether pauper, peasant, pontiff, or king, and that the physical consequences of it were the same for all.

This was also reflected in the growing popularity of the Transie Tomb. These were two-tier, sometimes three-tier tombs that would show the sculpted image of a noble in his armour or a bishop in his clerical robes, sceptre and orb in hand beneath which would lie the image of him decayed and eaten by worms. This was the time when death became the Great Leveller.

By the sixteenth century depictions of the Danse Macabre had become more erotic almost to the point of hysteria and death became associated with fornication and the sexual act. Both were viewed as moments of ecstasy and of orgasm and finality. So death had become linked to the creation of life itself. Even today, death and sex are the two subjects most likely to evoke a hysterical response.

In the eighteenth century, the so-called Age of the Enlightenment cast doubt upon the validity of God for the first time and what became important was no longer just the preservation of the soul for eternity but life itself.

The death of a loved one now became a deep personal trauma for those left behind and it was a grief considered both right and proper to express. The death of a child was to be particularly mourned and for which there could never be enough wailing. It was also around this time that major charitable works and organisations designed to secure the preservation of life for the more vulnerable first came to the fore.

The familiarity with death remained but the resignation to it diminished as the preservation of life became more important than the security and comfort of the soul. Indeed, the Victorian era has often been referred to as a Cult of Death.

It was a period of both increased agnosticism and religious revivalism and an obsession with the afterlife as expressed in the fascination with and popularity of spiritualism, but it was also a time of rigid rules of behaviour and of a strict moral code.

Victorians expected a significant period of public mourning for the deceased to be observed and the burden of this mourning fell invariably upon the women of any household with the widow and daughters of the deceased expected to wear only black in both public and private, sometimes with a veil. Smiling and laughter during the period of mourning was also frowned upon.

The bereaved were expected to be distraught but the grief had to be self-contained and despite it being public it was to be a sullen mourning. Nevertheless, the outward display of public grief was thought essential before the healing process could begin not just for the

individual concerned but society at large.

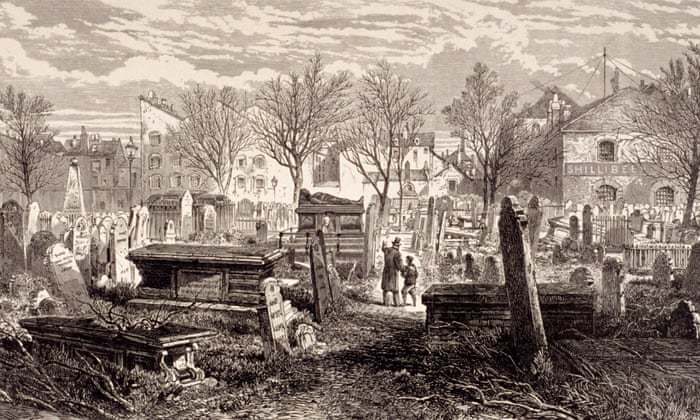

This was also a time that saw the introduction of the large park cemeteries beyond the usual confines of the Churchyard providing the opportunity for expressions of grief to be displayed in ever greater and bolder ways often in the form of ever more elaborate tombs and headstones. Sometimes it could be a large statue of the deceased in their pomp or of angels reaching up to the sky or in the case of children of siblings embracing or of them descending to heaven.

Epitaphs would often take the form of a poem, a brief summary of a man’s life his success and his failures. It also saw the return of the ritual of death.

With doors shut, the black curtains drawn, and the clocks stopped, once more family and friends were encouraged to gather at the bedside of the dying. Once death had been confirmed the body of the deceased would be placed in an open casket in a room in the house for neighbours to file past and pay their last respects.

The funeral itself would also be a time for display. Depending on the wealth of the individual a horse-drawn hearse, the horses adorned with ostrich feathers, would carry the deceased to the cemetery with a retinue of mourners following in its wake. Upon the arrival of the corpse a Minister of some denomination or other, regardless of the deceased own views in life, would preside at his death and burial. It was considered the duty of those still living to ensure that the dead had communion with God.

In the modern era people have distanced themselves from the process of dying. We rarely witness the event nor make elaborate preparation for it. We attend the funeral only which has become a hurried affair of little rite and few blessings, and we preserve no set period of mourning. As a result, death has become sanitised, it is something to be ignored, to be forgotten.

Grief is no longer a collective experience but has become individualised rarely extending beyond the boundaries of the immediate family. We have ceased to be familiar with death as a part of life but merely remain aware of its inevitability. We have come to fear it like nothing else and consider as something best not thought about.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: