Defending the Alamo

Posted on 29th January 2021

On 2 October 1835, Mexican Troops arrived at the town of Gonzales in Texas to retrieve a cannon that had been provided for the local townspeople to protect themselves from marauding Indians. At the time Texas was a province of Mexico and because of an increasingly unstable political situation the Governor had decided to remove a deadly piece of ordinance from potentially untrustworthy hands; but a militia had been hastily formed to prevent them from doing so and after a short firefight that left two Mexicans dead the troops withdrew – the Texan Revolution had begun.

In the years immediately preceding the outbreak of hostilities Texas had witnessed a large influx of American migrants, some of them were genuine settlers, others adventurers, but they were all hungry for land. They were also not willing to be dictated to by a largely absent power and disobedience of Mexican law was not only widespread but talk of independence from Mexican rule commonplace. In no time at all militias began to be formed and following the incident at Gonzales it began to be felt that perhaps the Mexicans would not resist any serious an attempt to break away. If this was the case then they had badly misjudged the man who ruled Mexico.

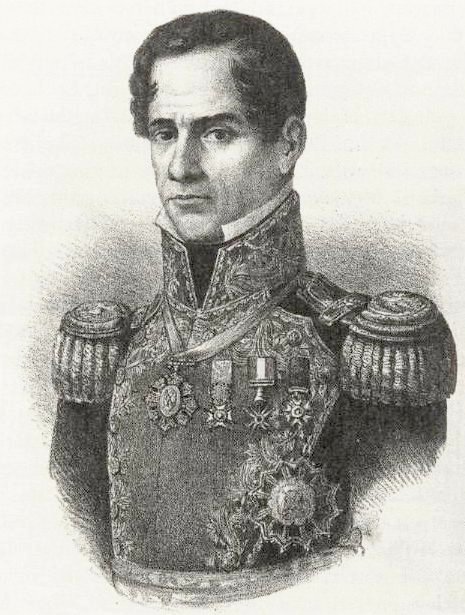

Antonio Maria Severino Lopez de Santa Anna, or, the Napoleon of the West, as he preferred to be known had abolished the Mexican Congress and assumed for himself dictatorial powers. He was a man who revelled in the grandeur of his position and never doubted for a moment his right to rule. He now set out to impose his will in every province of the country and those who resisted, or defied him in any way, he was determined to crush.

Following the incident at Gonzales, Santa Anna sent his brother-in-law Martin Perfecto de Cos, with reinforcements to San Antonio de Behar in the hope that their presence would help restore order but many of these troops were reluctant conscripts unwilling to confront an enemy willing to fight back. By October they found themselves surrounded and besieged by a larger force of Texian militia. Several unsuccessful but costly attempts to break the siege saw desertions mount until finally in early December four companies of cavalry, some 175 men in total, deserted. With his position increasingly untenable on 11 December, General Cos ordered those troops remaining in the town to surrender.

In their most significant victory so far more than 100 Mexican troops had been killed for the loss of just 4 Texians. Jubilant at their success the Texians now set about removing the few Mexican garrisons remaining in the province and within a few weeks of the defeat all had indeed been withdrawn from Texas. It just seemed to reinforce the view that they were not willing to fight. Santa Anna, however, was merely biding his time.

He believed that the United States Government was behind an attempt to absorb Texas and he did not want to risk a diplomatic incident and possible direct interference by the U.S Military. So, he acted with caution while in the meantime, he formed his Army of Operations to retake the province by force.

At the town of San Antonio de Behar was a ramshackle old Catholic Mission Station with a Church that had previously been used as a fort known as the Alamo; though no longer considered adequate for defence the Texian forces in the town did their best to fortify it.

Little could they have known as they dug trenches and put-up ramparts in their little Mission Station that it would not only provide a pivotal moment in the rebellion but the rallying cry for the liberation struggle to come.

Political moves towards an independent Texas had been led in large part by Steve Austin, a Virginia lawyer who had done more than anyone to encourage Americans to settle in Texas and to lay the legal framework for the declaration of a Sovereign Republic. But how to do so when Santa Anna refused to negotiate, and the United States Government refused to intervene posed a problem. They could fight of course. After all, America had won its independence by force of arms, but they had no army. One had to be organised from scratch.

All they had in the meantime were some hastily formed militias and a handful of volunteers.

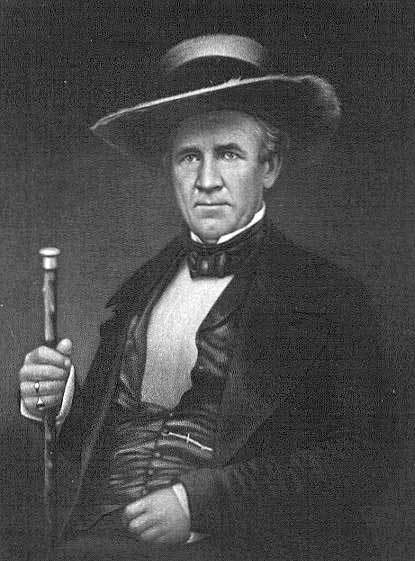

The task of recruiting, forming, and training an army ready to fight would fall to Samuel Houston, a heavy drinking, hard living, plain speaking Virginia born, ex-Congressman from Tennessee who did not suffer fools easily. He was also an experienced soldier, ambitious, determined, and single-minded.

The Siege of the Alamo itself, however, would always be associated with the names of three men: David Crockett, James Bowie, and William Barret Travis. Two were already legends in their own lifetime the other would become so after his death. They were also very different men who shared no great love for one another but were to be thrown together as comrades in a life and death struggle which perhaps none of them at the time could have foreseen.

Davy Crockett was born on 17 August 1786, in East Tennessee, to poor parents who carved out a precarious existence in the wilderness, and he was to learn the arts of the backwoodsmen, to hunt, trap, and skin animals from an early age. Fearing expulsion from the school his father had saved hard to send him to for beating up another child he ran away from home; though only 13 years old at the time he was to stay away for three years and much of his legend was born during this time as the young boy surviving alone in the wilderness.

In September 1813, he enlisted in the Tennessee Volunteers and served with distinction in the Creek Indian War. With his reputation enhanced as a brave and audacious man deadly with a musket and ruthless with a knife, upon his discharge he was promoted to the rank of Colonel in the Tennessee State Militia. By this time his life was being written up and sensationalised in Dime Novels, some financed by, himself; and a successful stage show based on the story of his life was touring the country. All kinds of heroic deeds were now being accredited him, almost all of them mythical such as being able to ride a lightning bolt, leap the Mississippi in a single bound, or kill a bear in unarmed combat.

With his legend firmly fixed in the public imagination a career in politics now beckoned.

In 1826, he was elected to Congress for the first time as Representative for the State of Tennessee. He lost his seat in 1830 but won it back again two years later; though always much more than the simple backwoodsman he liked to portray himself as he was always a better hero than he was a politician. When it became inevitable that he would lose the forthcoming election he told his constituents: "You may go to Hell, I'm going to Texas." He did just that, his destination - the Alamo.

Jim Bowie, the legendary knife-fighter, was born in Kentucky in 1796, the ninth of ten children. Unlike Crockett, Jim Bowie's upbringing was both comfortable and conventional.

His father was a prosperous farmer and slave-owner who ensued that his children were provided with a good education.

Young Jim was then both literate and articulate and could speak French and Spanish fluently. He also befriended the local Indians and learned to hunt, trap, plant, and become proficient in the use of the knife and the gun. By 1812, the family had settled in Opelousas, Louisiana and the sixteen-year-old Jim had grown to be a resourceful and in many ways unscrupulous young man.

In 1818, he and his older brother Rezin developed a relationship with the pirate Jean Laffite for the illicit importation of slaves. This made them both rich and they were to use their money to move into land speculation.

Jim Bowie was to become a hard drinking short-tempered man utterly ruthless in business who, made enemies easily and knew how to hold a grudge. When the Sheriff of Rapides Parish, Louisiana, Norris Wright, who was also a Bank Governor had been instrumental in refusing Bowie a loan he vowed revenge. They had already had more than one physical altercation when on 19 September 1827 they both attended a duel on a sandbar just outside Natchez, Mississippi. Though they were not the protagonist they soon would be.

The duel itself ended amicably enough with neither of the competing parties being hurt but a fight soon broke out among the attendants, gunfire was exchanged, and Bowie was shot in the hip but drawing his knife went for his assailant. Wright seeing this, intervened, and hit Bowie so hard over the head he broke his pistol. A stunned Bowie fell to the ground and Wright now fired at him but missed. He then drew his sword cane and thrust it into Bowie's chest but as he went to remove it from the body of his seemingly helpless victim Bowie dragged him to the ground and disembowelled him with his knife. As Bowie rose to his feet with the sword still protruding from his chest he was stabbed and shot again by the now dead Wright's associates. He somehow miraculously survived.

The fight at the Sandbar made Jim Bowie famous, and the knife he used that day designed by his brother Rezin, with its blade more than 9 inches long and one and a half inches wide, became even more famous. In 1828, a year after the fight at the Sandbar, Jim Bowie moved to Texas.

Very much a man on the make and was determined to assimilate himself into Mexican society and culture. As Roman Catholicism was the only permitted religion he converted and in 1830, he applied for and received Mexican citizenship. He then married into the Mexican aristocracy when he wed Maria Ursula de Veramendi, the 19-year-old daughter of his business partner.

By 1832, he owned more than 700,000 acres and had an estimated personal fortune of $225,000.

On 2 September 1831, he set out with his brother Rezin and nine others to find the legendary silver mine of San Saba. On 1 November they were attacked by a party of 150 Indians and in a sustained 13 hour fire fight they killed more than 30 of the Indians forcing them to withdraw.

News of the attack had leaked back to San Antonio de Behar, and no one had expected to see any of the party alive again. When they returned a few days later everyone was astounded.

The incident only served to reinforce Bowie's reputation as a fierce fighter but even he was not immune to tragedy. Between the 6th and 14th of September 1832, his wife and young children all died in a cholera epidemic. He had earlier sent them away to what he thought was a place of safety. He was consumed by the guilt he now felt, and the death of his family affected him greatly. His ill-temper worsened, and he was now rarely seen sober.

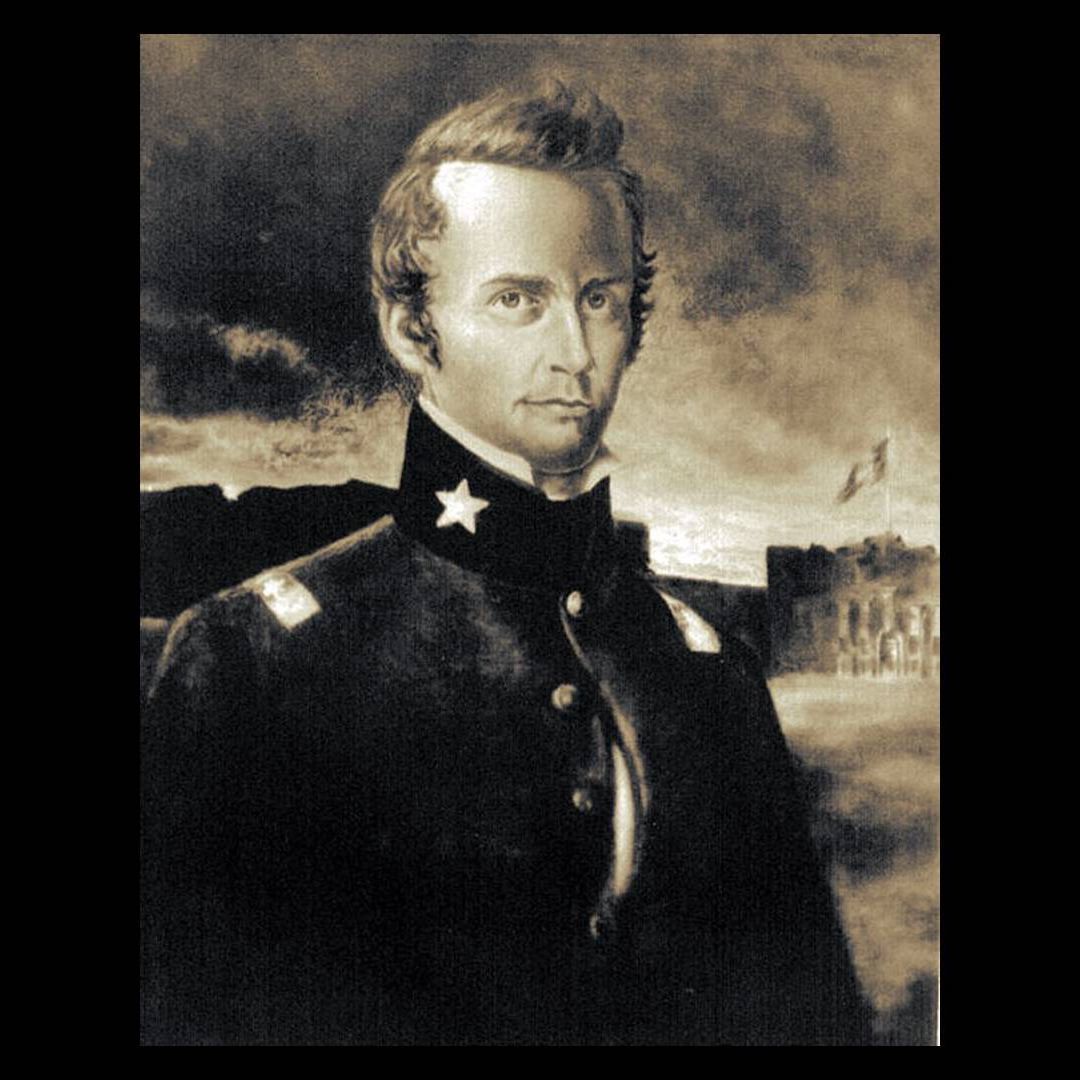

William Barret Travis, who would command the Texian forces at the Alamo, was born in South Carolina on 9 October 1809, though he was actually raised and educated in Alabama. He was from a comfortable background and had already qualified as a lawyer by the time he was 19. On 26 October 1828, he married Rosanna Cato, but the marriage was not a success and early in 1831 he abandoned his wife and two young children and fled to Texas.

Travis was an arrogant and pompous man who certainly had a high opinion of himself even if it was not an opinion shared by many who knew him. He considered himself to be the quintessential southern gentleman, though he barely behaved like one as the detailed diary of his sexual exploits he kept would appear to indicate.

In January 1835, he was commissioned Lieutenant-Colonel in the Texian Cavalry, the problem was that there wasn't a Texian Cavalry and Travis soon found himself responsible for finding people to serve in one. By the time of the outbreak of hostilities with Mexico he had built it into a force of 384 Officers and men.

In 1835, the Alamo was garrisoned by fewer than 100 men and provided a weak defensive position considered to be of little or no strategic significance. It did, though, have 19 cannon, and Sam Houston, in command of the Texian Army who had neither the men nor resources to sufficiently reinforce the Alamo, did want the cannons. He sent Jim Bowie with 30 men to dismantle the Mission and bring away the guns. The Alamo's Commander Colonel James Neill argued vehemently that the Alamo stood directly in the way of Santa Anna's march into the heart of Texas. Defending it would buy valuable time for Sam Houston - Bowie, agreed.

On 3 February, Travis arrived at the Alamo with 25 soldiers of the Texian Army. Five days later to great fanfare Davy Crockett turned up with 14 men of his Tennessee Mounted Rifles.

On 11 February, Colonel Neill announced that he had to leave his post temporarily to sort out some legal problems at home and handed over command to Travis as the senior ranking Officer remaining at the Mission. The volunteers however refused to serve under Travis and elected Jim Bowie to lead them. Bowie immediately celebrated his election by getting drunk with his men and going on the rampage in nearby San Antonio de Behar. The always sober Travis deplored Bowie's behaviour and told him so.

There had always been a great deal of friction between the two men, Travis considering Bowie a lout, Bowie considering Travis a pompous dandy. No doubt Bowie would have preferred to sort out their differences man-to-man. Travis, understandably perhaps, thought otherwise. So, they instead agreed to joint-command of the Alamo.

Any internal disputes and personal rancour became secondary when to everyone’s surprise on 23 February, 1,500 troops of the Mexican Army occupied San Antonio de Behar.

Panic ensued, as Travis ordered the abandonment of the town and surrounding area, His troops, gathering up their belongings and some bringing their families with them retreated into the Alamo. Later that same day the Mexicans raised the ‘Bloody Flag’.

Santa Anna had declared all those in a state of rebellion in Texas to be pirates and outside the normal rules of war. There would be no quarter given. In response, Travis ordered the firing of the Alamo's largest cannon.

A furious Jim Bowie, who knew the Mexican Army's senior commanders and had been trying to negotiate a settlement, believed Travis had acted hastily, and confronted him over the issue. When he was informed, however, that Santa Anna would only accept an unconditional surrender and that the treatment of prisoners would be at his discretion, he stood firmly by Travis. The following day, Travis wrote his famous Open Letter to the People of Texas and all Americans in the World:

"Fellow citizens and compatriots - I am besieged, by a thousand or more Mexicans under Santa Anna - I have sustained a continual bombardment and cannonade for 24 hours and have not lost a man. The enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion, otherwise the garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is taken - I have answered that command with a cannon shot and our flag still waves proudly from the walls. I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call on you in the name of liberty and patriotism and everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid with all dispatch. The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily and will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible and die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his honour and that of his country - Victory or Death."

It is estimated that there were 189 defenders at the Alamo Most of whom, originated from the Southern States but 34 also came from overseas including 27 from Britain. Only 9 could be described as natives of Texas and most of these were of Mexican descent. Almost all were volunteers.

For the first few days of the siege there was very little activity except for a near continual bombardment. At first Travis answered like with like but then decided to conserve his ammunition for what he knew would be the inevitable assault. At times he would call upon Crockett's Tennesseans to fire upon the Mexican lines. Such was their accuracy of shot that he considered it to be as good as any artillery bombardment.

On 24 February, Jim Bowie collapsed from an unknown illness, though probably tuberculosis, and was confined to his bed. Travis was now in sole command. Later in the day the Texians made a sortie from the walls to force 200 Mexicans who had taken shelter in some nearby huts to withdraw. The huts were then burned.

Travis was constantly sending out couriers with messages pleading for assistance. As a result, news of the siege quickly spread. Volunteers began to gather in Gonzales hoping to join up with Colonel James Fannin. He was garrisoned at Goliad, some 90 miles from the Alamo, with 450 men and it was expected that he would embark on a mission to relieve the Alamo.

On 26 February, he ordered 320 men with 4 cannon to march for the Mission Station.

They had travelled no more than a mile from Goliad when Fannin revoked the order, and they were forced to return. The men in Gonzales unaware of this continued to the Alamo. They arrived on 27 February, all 32 of them. Travis could barely disguise his disappointment.

It was becoming increasingly clear to Travis that there would be no Relief Column. He had earlier sent Crockett on a scouting mission to see if there were any signs that Fannin was on his way, there were none. He had tried to maintain morale by telling his men, most of whom were volunteers that Sam Houston would not allow them to die in the Alamo. He now had to face the reality, and his men would have to do so also.

On the afternoon of 5 March, Travis ordered his men to assemble. He told them that no reinforcement was likely, that an attack was imminent, a Mexican victory inevitable, and that no quarter would be given. He then drew a line in the sand and said that any man who wished to remain with him at the Alamo should cross the line. Those who wished to make their escape as best they could, would be allowed to do so without repercussions.

Only one man refused to cross the line, Louis ‘Moses’ Rose, an illiterate Frenchman who spoke barely a word of English and was a veteran of Napoleon's invasion of Russia. He was to later escape over the Alamo's walls before the final battle began and has been known ever since as the coward of the Alamo’. Later that day Travis sent his last courier, James Allen, little more than a boy, with dispatches and letters from the men to their families.

At 05.30 on 6 March, while it was still dark, the Mexican Army began its assault on the Alamo. The Texian sentries posted outside its walls had their throats cut as they slept before suddenly the garrison were awoken by cries of Viva Santa Anna! Viva Mexico!

Travis rushed to his post shouting as he did so "Come on boys, the Mexicans are upon us, let's give them hell." As he passed his Mexican volunteers he said "No rendirse, muchachos" (No surrender, boys). The Texians loaded their cannon as quick as they could and with anything they could find, nails, bolts, horseshoes. It all made for effective grapeshot, good at close range. Travis, however, was one of the first men to die when leaning over the wall to fire upon the advancing Mexicans he was killed by a single bullet to the head.

The fighting was fierce as the Texians pushed away the Mexican scaling ladders and forced those already on the walls to retreat, and with little time to reload much of the fighting was hand-to-hand. Even so, the Texians repulsed not just one but two Mexican assaults. But they quickly regrouped for a third and final assault.

The simple fact was the Texians did not have the manpower to effectively defend all of the ramparts and as casualties mounted gaps began to appear and the Mexicans soon began to flood into the Alamo's interior. As had earlier been agreed, once the walls had been breached the Texians withdrew to the barracks and the Chapel for a last stand.

Those who could not reach the inner defences now began to try and flee the battle. Some made for the San Antonio River, others for the East Prairie but Santa Anna had ringed the Alamo with 500 cavalry with the express purpose of preventing any such attempt to escape - the fleeing men were cut down and killed.

The last group still defending the outer-walls were Davy Crockett and his Tennesseans.

The accuracy of their fire had taken a terrible toll on the advancing Mexicans but now with no time to reload they were reduced to using their rifles as clubs and fighting with knives. It was a desperate struggle, but by now the battle was nearing its denouement.

Meanwhile, Jim Bowie, barely conscious, was propped up in his bed against the wall. As the Mexican troops burst into his room, he fired the pistols that had been placed in his hands and was bayoneted to death as he reached for his famous knife. An eyewitness said that they thrust the bayonets so hard and deep into his body that they were able to lift him up by them.

The Battle for the Alamo, with little organised defence remaining, had descended into a massacre. Many Texians fought on, others tried to flee, and some tried to surrender, all were killed. Such was the fury and bloodlust of the Mexicans that they continued to fire at and bayonet the bodies of the Texians long after they were dead.

Some now believe that Davy Crockett and a small number of his Tennesseans were taken prisoner and executed after the battle on the express orders of Santa Anna; and that after pleading for the life of his men and it becoming evident that his pleas would be ignored he faced his death with fortitude and courage.

A former slave named Ben however, who was working as a cook in the Mexican Army, reported seeing the body of Davy Crockett amidst the bodies of numerous of his foes.

It had been a fierce and bloody struggle but now it was all over. There were just a handful of survivors. One was believed to be Henry Wardell, who escaped over the wall during the assault and managed to hide long enough to make his escape. Another was Brigido Guerrero, a deserter from the Mexican Army who had joined Juan Seguin's volunteers. He had locked himself in one of the Alamo's cells and made out to the invading troops that he had earlier been taken prisoner.

A number of women and children, who had been hiding in the Sacristy, also survived. Among these were Jim Bowie’s two sisters-in-law and Susanna Dickinson (the wife of Almaron Dickinson, one of the last to die in the fighting) and her daughter. She was to be one of the more reliable witnesses to events, until the bottle took hold of her in later life.

Both Bowie's slave Sam, and Travis's slave Joe, were also spared.

Santa Anna, who had shown little respect for the fallen enemy denying them a Christian burial and instead having the bodies piled in heaps and burned was at least more gracious towards the survivors and after interviewing each one provided them with a blanket, two silver pesos, and had them escorted from the camp.

Some 220 Texians had been killed at the Alamo. Mexican casualties were probably not as high as legend suggests but even so are believed to have been around 250, though no precise figure exists. This suited Santa Anna however, for as he saw it the more blood spilt, the greater the victory.

News of the defeat at the Alamo shook the Texians confidence in ultimate victory and worse news was to follow when less than three weeks later the man who had failed to come to the Alamo's assistance, James Fannin, now found himself in his own life and death struggle.

He had been forced to withdraw from Goliad but during his march north had been caught in the open and attacked by a superior Mexican army. Having suffered around 150 casualties unlike the defenders of the Alamo he decided to negotiate surrender. Believing that he had secured an assurance that none of his men would be harmed they laid down their arms.

On 27 March, Palm Sunday, 1836, the 342 survivors of his force, including Fannin himself, were marched back into Goliad and executed.

In what now became known as the "Runaway Scrape", Sam Houston withdrew all his forces to avoid any contact with Santa Anna's army. He also gave up most of Texas in doing so. As far as Santa Anna was concerned the war was as good as won and he became complacent. The ambitious, determined Houston, however, was just waiting for the right time to strike.

At around 17.00 on 21 April 1836, Sam Houston ordered his army, some 900 men, to attack the Mexican encampment across open ground in broad daylight. It was as brave as it was audacious, but Houston knew that the Mexicans would be taking their siesta. He was right. Some of the Mexican troops were washing their clothes in the river but most were asleep, Santa Anna, who had posted no guards, was taken completely by surprise.

What was, to become known as the Battle of San Jacinto was in fact a massacre as bloody and brutal as anything that had occurred at the Alamo and Goliad. The fighting for what it was lasted barely 20 minutes, but the killing continued long after with some 600 Mexicans losing their lives and a further 730 captured, the remainder fled. The Texians had lost just 9 dead and 30 wounded.

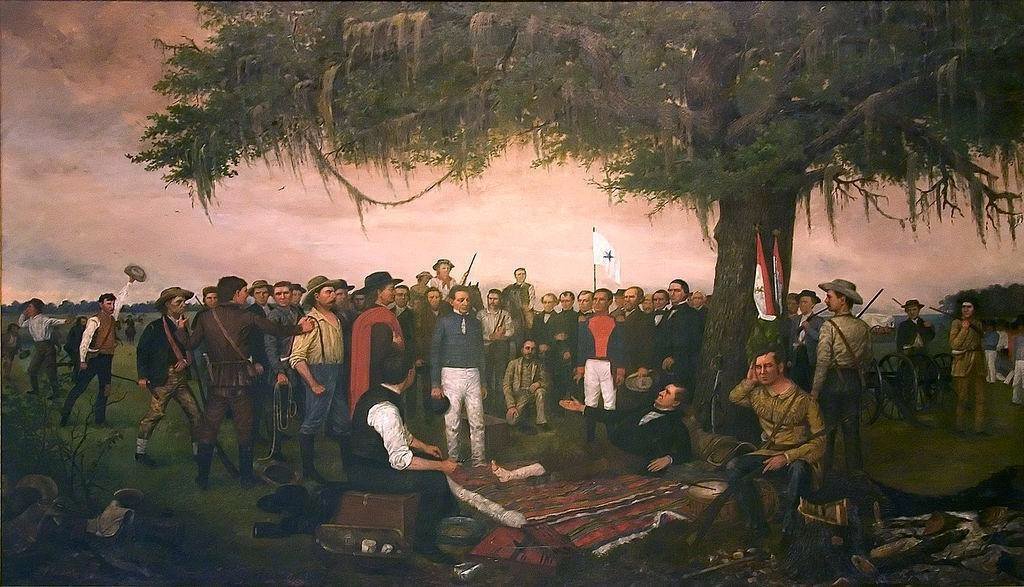

Santa Anna was captured the following day having shed his grand uniform for that of a private soldier, but his ruse didn’t work for when captured and brought to the Texian camp he was recognised by those prisoners who saluted him. His silk underwear only confirmed his identity.

Taken before Sam Houston he said: "That man may consider himself born to no common destiny who has conquered the Napoleon of the West; and now it remains for him to be generous to the vanquished." To which Houston replied: "You should have remembered that at the Alamo."

Despite demands for Santa Anna to be hanged from the nearest tree his life was spared, Sam Houston needed him to negotiate a proper legal separation of Texas from Mexico which under sufficient duress he did.

The Republic of Texas had been declared on March 2, 1836, the month before the Battle of San Jacinto now it was official; and like all nations it also had its martyrs and its creation myth. Under its first President Sam Houston it would exist as an independent State for ten years before by agreement being absorbed into the United States of America.

Santa Anna, like the proverbial bad penny he was just would not go away and would be President of Mexico on a further seven occasions – still the Napoleon of the West.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, War

Share this post: