Edgar Allan Poe: An Eternal Mourning

Posted on 8th October 2021

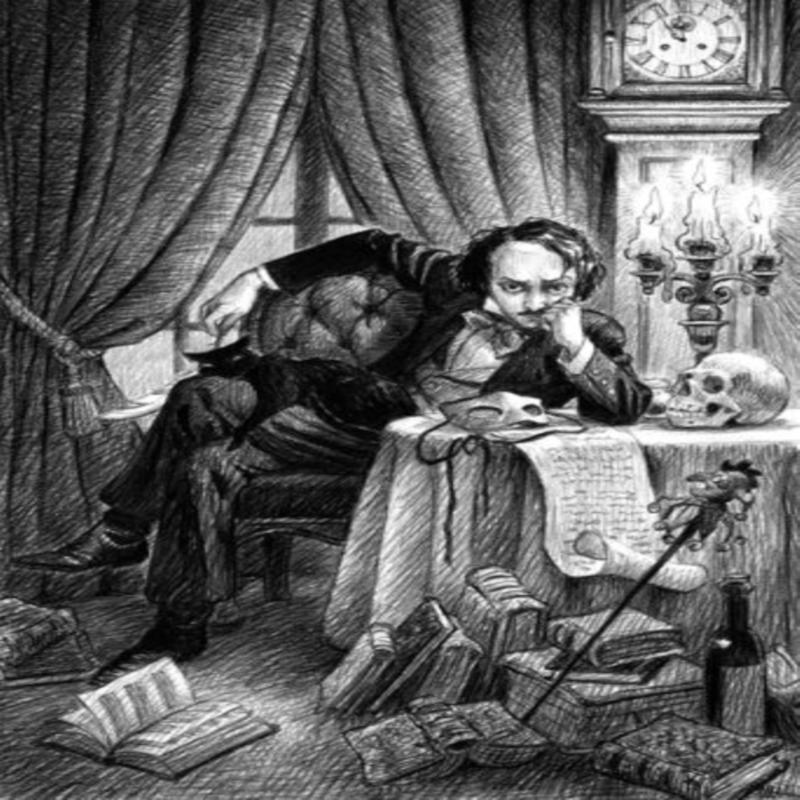

Long considered the master of mystery and suspense, the herald of horror, and with creating the first fictional detective Edgar Allan Poe’s own life, and indeed death, was no less beset by torment and shrouded in uncertainty than those who were the figment of his often-fevered imagination.

He was born plain Edgar Poe on 19 January 1809 in Boston, Massachusetts, to actor parents neither of whom he would ever know. His father, David Poe, abandoned the family before Edgar was a year old and his mother Eliza died of bronchial tuberculosis a little more than a year later, so baby Edgar and his siblings Henry and Rosalie were farmed out for adoption.

Edgar was taken in by the Allan family from Richmond, Virginia, seemingly at the insistence of Frances Allan and only reluctantly by her husband John, hence the adoption was never made official and in law at least they were to remain his foster-parents.

Frances Allan showered the young Edgar with affection ensuring that he lacked for nothing but John Allan a caustic and hard-headed businessman maintained his distance providing for him and treating him like a son when in public but otherwise rarely thinking of him as one. Even so, for his support he expected gratitude which was rarely forthcoming, and their relationship was to remain a fractious one only getting more so as the years passed.

Baptised into the Episcopalian Church at the age of six, Edgar was never a regular churchgoer and for all the tragedy in his life religion never dominated in either thought or deed thereby providing little solace.

In 1815, the Allan’s travelled to Britain where they were to remain for five years during which time Edgar attended Boarding School where he readily added the name Allan to his own in tribute to the foster-mother he adored and as a boy he was very different to the man of popular imagination – he was athletic, participated enthusiastically in sports, and was an outstanding swimmer though he was later to denounce all such activity as a nonsense easily imitated by apes.

Raised to be a southern gentleman in this respect he didn’t disappoint being always courteous and polite exuding bonhomie and a predictable charm.

Aged 15, he became besotted with the mother of a friend who was to be his first great love and when she died in 1824 of the dreaded consumption that had taken his own mother it was his first experience of the deep grief and sense of loss with which he was to become all too familiar.

An avid reader Edgar’s love of storytelling manifested itself in his desire to be a writer and more particularly a poet, an unmanly pursuit according to his foster-father who could not understand his disinterest in business, a grubby profession shorn of any beauty or romance.

As far as John Allan was concerned if his foster-son required money he should work for it and they argued frequently and it seemed only Frances Allan could placate the ire of both, and she was dying.

Edgar was distraught but not seemingly John Allan for even as his wife lay bed-ridden and struggling for life he was having sexual relations with other women often bringing his lover’s home. A distressed Edgar publicly criticised his foster-father widening even further the rift between them and for no better reason than to get Edgar out of the house in February 1826, John Allan paid for him to attend the University of Virginia, but he would provide for nothing else – no books, no clothes, and no food.

Even so his time at university was a joy to Edgar whose natural grace and eloquence charmed the other students and more than made up for his dishevelled and unkempt appearance as he entertained them with stories of the imagination and readings of his poetry. But as the months wore on his penurious condition worsened and he was reduced to burning his own meagre furniture for fuel.

Eventually what money he had he decided to gamble but rather than providing the path out of poverty it left him $2,000 in debt and he wrote often to his foster-father pleading for support but receiving nothing back. It seemed clear to Edgar that with the death of his wife pending, John Allan no longer wanted anything to do with him. In despair he wrote:

“Richmond and the United States are too narrower a sphere and the world shall be my theatre. If you determine to abandon me here, I take my farewell, neglected I will be doubly ambitious and the world shall hear of the son who you have thought unworthy of your notice.”

Needing to escape his creditors he travelled to Boston where he enlisted in the army under the assumed name of Edgar J Perry. It was not his intention to embark upon a military career he still harboured ambitions to be a writer the army merely facilitated a means of escaping his creditors, but he took surprisingly well to military discipline and was to prove a good soldier.

Aged 20, he paid to have published two volumes of his poetry which were neither reviewed nor much read, and he made a loss, but he could at least now consider himself a Man of Letters.

On 28 February 1829, Frances Allan died, and it was at her funeral, perhaps out of a sense of guilt that John Allan agreed to support the clearly distraught Edgar’s application to attend West Point Military Academy for Officer training. But his heart was never really in it and in February 1831 he was court-martialled and dismissed from the service for non-compliance with the rules and behaviour unbecoming an Officer. It was to prove the final breach between Edgar and John Allan.

Following his ejection from West Point, Edgar moved to Baltimore to live with his aunt Maria Clemm, her young daughter Virginia, and his older brother Henry where he at last decided to dedicate himself to his chosen profession.

A literary career was a precarious one for a man of few means and he was one of the few who tried to live off what he could earn by writing alone for with no effective copyright laws in place any written work however highly regarded rarely provided financial security and the poorer a writer the more he was at the mercy of his publisher.

Not long after arriving in Baltimore his brother Henry, to whom he had been particularly close, died of liver failure. It was another loss to endure but saddened though he was he would not be diverted from his chosen course even if he embarked upon his literary career more in hope than expectation. Even so, he did get some prose works published in local newspapers and periodicals.

In 1833, he achieved a breakthrough when his short story MS in a Bottle won an award which brought him to the attention of prominent people in the arts who provided him with access to literary circles.

It was in MS in a Bottle that he first gave expression to the theme that came to dominate not only his writing but his life: “It is evident that we are hurrying onwards to some exciting knowledge, some never to be imparted secret whose attainment is destruction.”

Death, it seemed was not merely his fascination and his greatest dread but also his partner in life, and the melancholia it induced the leitmotif of his existence, overwhelmed him.

In time he was to become a respected and admired, if rarely popular writer; for many his work was dark and impenetrable offering no prospect of salvation or redemption even to those worthy of God’s blessing, and this at a time of religious revivalism when hope not despair infused the soul of man; his analysis of the human condition without the intervention of the Divine was simply unthinkable to many, perhaps even cruel.

His literary contacts helped him to get the job of assistant-editor of the Southern Literary Messenger.

Edgar’s easy-going southern manner belied a savage pen, and he was to accumulate enemies from among those who fell-foul of his incisive and unremitting literary criticism including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, then America’s favourite poet who he dared to accuse of plagiarism.

His harsh words for those whose work failed to meet his very high standards sold magazines however, and he was to work as a reviewer for many other publications, but the hours were long and the pay poor.

By 1834, John Allan lay on his deathbed and learning of this Edgar as his foster-son though not legal heir felt it was his responsibility to be in attendance, but he was greeted with such hostility that not long after arriving he departed.

If he thought reconciliation might be possible and he might receive an inheritance as a result, then he was sorely disabused. His foster-father died a very wealthy man, but he left Edgar nothing.

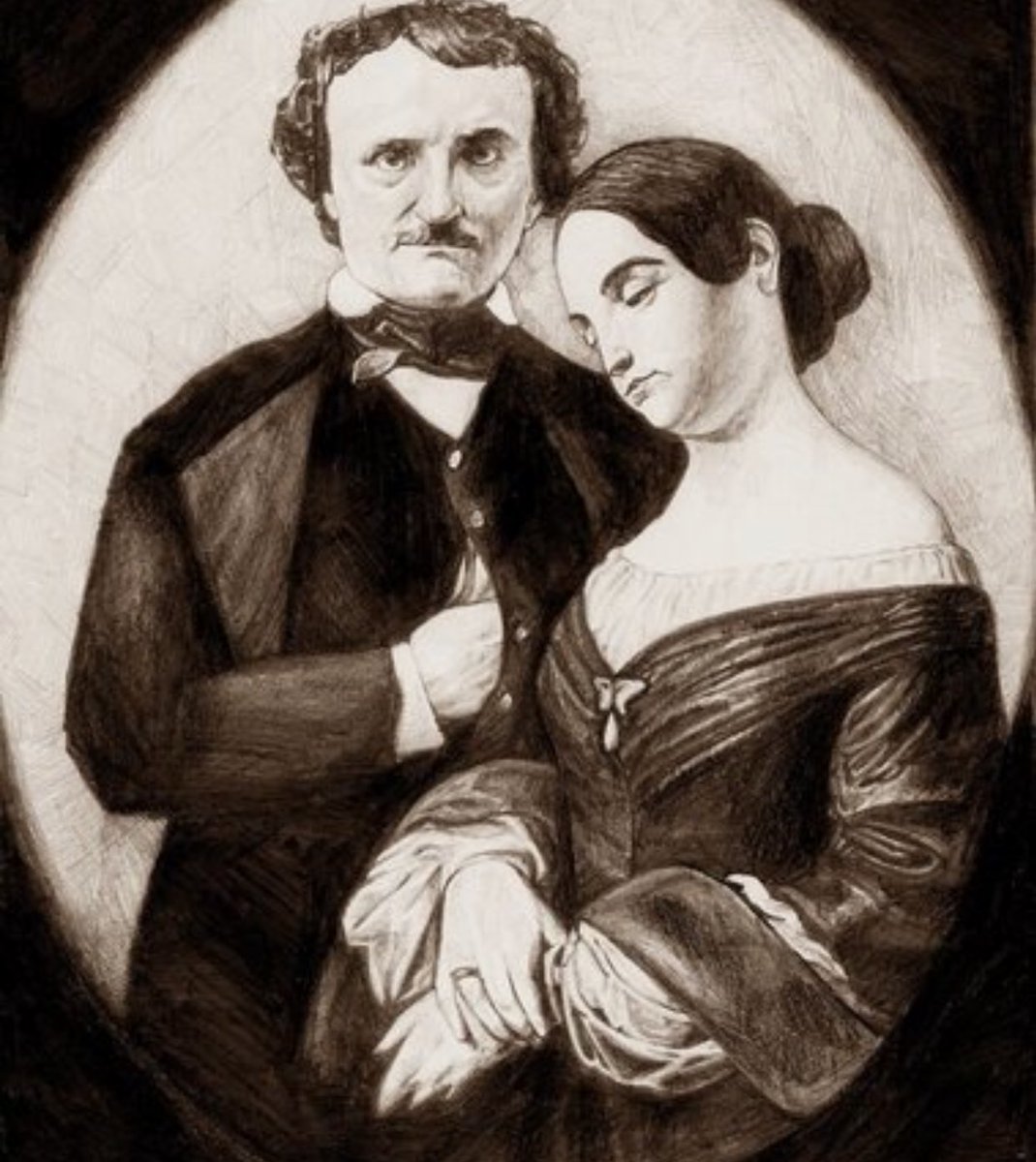

On 16 May 1836, Edgar married his cousin Virginia Clemm even though she was only 13 years of age, and he was 26. To try and avoid scandal the marriage certificate was falsified to show her age as 21 and witnesses were called to testify that despite her youthful looks this was indeed the case.

It was by all accounts a happy marriage but whether they had a sexual relationship remains a matter of conjecture. Certainly, Edgar did not so much love as worship the women in his life and sex would no doubt sully the perfection, and he often referred to Virginia as a maiden or his sister, but his letters to her despite an often child-like tone do not lack in passion.

Edgar and Virginia delighted in each other’s company and the Clemm household took on a playful aspect as they would romp in the garden and regularly entertain at night but in truth Edgar was struggling to provide for the family and the light-heartedness that prevailed hid a great deal of anguish which he overcame by drinking heavily.

In 1839, he published a collection of his work Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, but it sold few copies.

One night in January 1842, Virginia was playing the piano as she would often do for the entertainment of Edgar and Maria when she began to cough violently and uncontrollably. By the time she recovered her composure blood had appeared on her lips and was trickling down her chin – Edgar knew what his meant, his beloved Virginia had consumption – she was going to die.

Tuberculosis was not immediately fatal and the young and vigorous Virginia would take a long time dying and years of torment would follow for Edgar as periods of apparent recovery when Virginia would once more sing for him and tend to the roses in the garden filled him with hope only for her to lapse once more into a pitiful figure unable to stand, shivering from the cold, needing to be fed, and in great pain.

Edgar’s reliance upon alcohol to see him through the day now accelerated and he was a bad drunk unable to disguise its effects or control his behaviour.

Indeed, needing a more secure income to provide for Virginia’s medical care he had used his connections to arrange a meeting with President John Tyler at the White House to apply for a government post but the drinking had taken such a hold that he arrived dishevelled, disoriented, and clearly the worse for wear and had to be sent home. A second appointment was arranged but his behaviour was barely less erratic than it had been at the first – he did not get the job.

On 29 January 1845, his poem The Raven was published in the Evening Mirror newspaper. It proved a sensation and made Edgar Allan Poe almost overnight one of the most well-known literary figures in America but he had been paid just $9 for its publication and though it was widely syndicated it only ever made him $14.

But at last, he had an audience for his work and he revelled in the fame it brought him embarking upon a series of public readings that proved hugely popular and provided a valuable source of income but life at home remained unremittingly sad as Virginia’s illness began to overwhelm her and in the final months of her life Edgar began to seek affection elsewhere seemingly with her approval, though she was in little state to argue otherwise.

On 29 January 1847, Edgar wrote to a friend: “My poor Virginia still lives, although failing fast and in much pain.” The following day she died, aged just 25.

Five years earlier Edgar had published a short story Masque of the Red Death in which there could be no escape from the unavoidable sickness marked by blood.

He had mourned for his mother as an orphan does, he had mourned for his foster-mother as a son does, he had mourned his beloved Henry as a brother does, and now he mourned for his wife as a lover does. The dreaded scourge of consumption had struck once more, and the shadow of his melancholy would never leave him and he drank and took drugs to desensitise its bony fingers.

He had always believed that woman was the soul of man and for him life without female companionship was simply not worth living but his attempts to court women met with only limited success. His life it seemed reflected his art and was to do so unto death.

On 3 October 1849, the noted poet and author Edgar Allan Poe was discovered wandering the streets in a ‘state of some distress and in need of immediate assistance.’ Unaware of his surroundings, incoherent of speech, without trousers and wearing clothes too large and clearly not his own he was incapable but not drunk.

Taken to a local medical centre by concerned citizens he died four days later having never fully recovered consciousness and unable to explain what had happened to him. He left few clues other than the oft repeated name Reynolds and the constant refrain of Oh dear.

A post-mortem arranged by his enemies to destroy his reputation failed to do so but his own behaviour, marrying his 12 year old cousin and being frequently seen drunk in public, had done little to enhance it but The Raven and shortly after his death the publication of Annabelle Lee secured his fame and popularity, and though he didn’t create the gothic novel he became its most outstanding exponent with stories such as Pit and the Pendulum and The Fall of the House of Usher among many others.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: