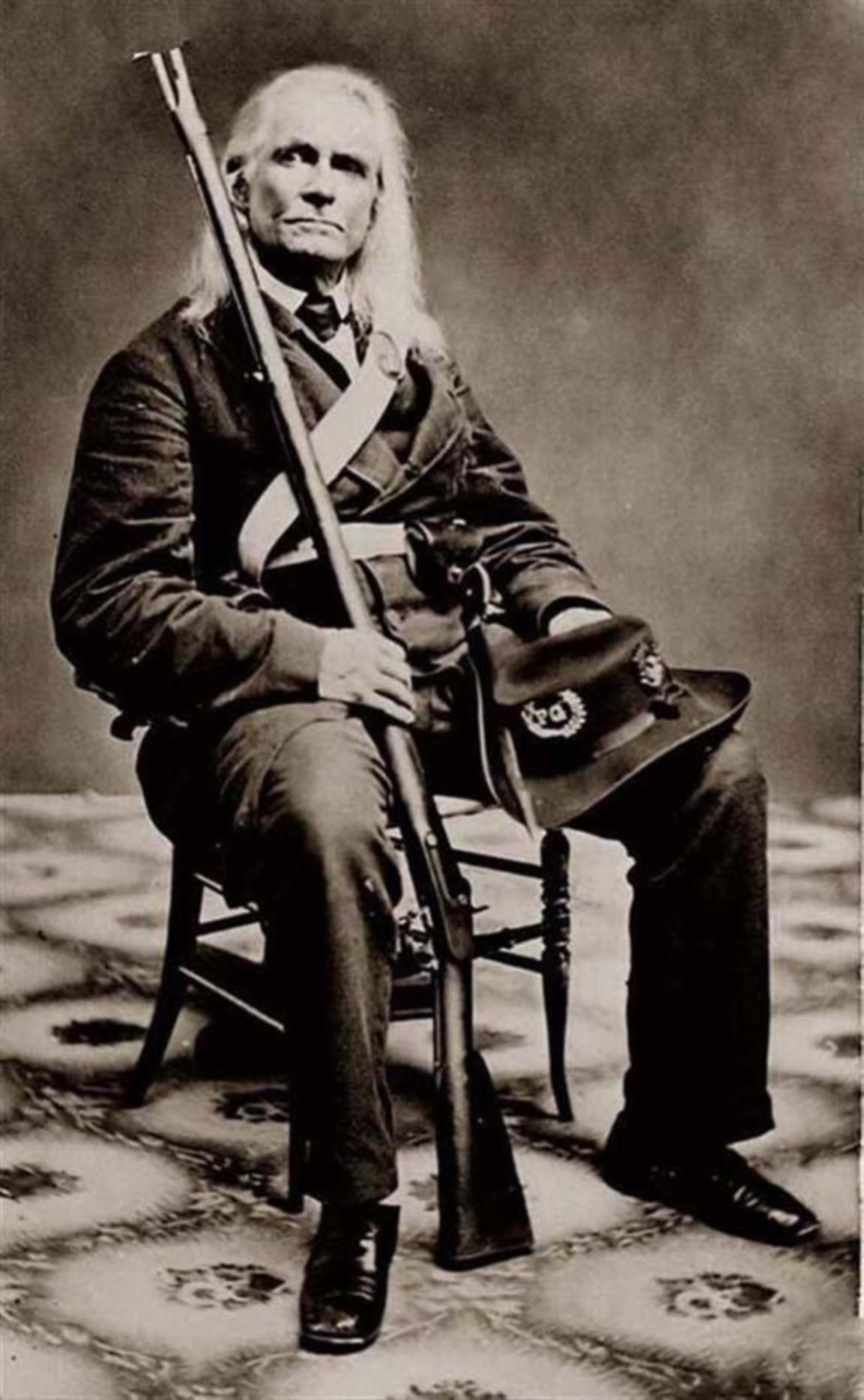

Edmund Ruffin: Firing the First Shot

Posted on 1st August 2021

Rarely in a war is it known who fired the first shot but in the conflict between the States we know exactly who it was. Edmund Ruffin would write for himself a page in American history by unleashing the cannon ball upon Fort Sumter that began a war which like so many before and since was expected to be over with quickly but was in fact to last four long years, take over 700,000 lives, and change the country forever.

But for Edmund Ruffin on that chilly April morning, it was the fulfilment of a dream, the culmination of a lifelong mission.

Born on 5 January 1794, in Prince George County, Virginia, the son of a pro-slavery plantation owner he was raised in comfort but despite being recognised as a bright and intelligent young man he neglected his education and left College early to follow more personal interests namely the pursuit of his future wife, Susan Travis.

In 1812, he volunteered to fight against the British but was disappointed not to see action before peace was concluded and was at something of a loss with what to do with his life, but all this was to change when he inherited his father's plantation at Tidewater and suddenly began to take life very seriously indeed.

Convinced of the inferiority of the Negro race he believed slavery to be their natural condition and that gratitude should be forthcoming to the white man who had taken upon himself the responsibility for their well-being. Others, mostly in the north thought otherwise and it would be the so-called ‘peculiar institution’ that would divide the country north from south and provoke the future conflict

Already a southern nationalist Ruffin thought his study and deep understanding of agriculture could be utilised to help make the slave states self-sufficient so helping to free them of the northern yoke. He had already written several books and pamphlets on agronomy advocating a more scientific approach to farming and was an adviser to the Virginia State Legislature.

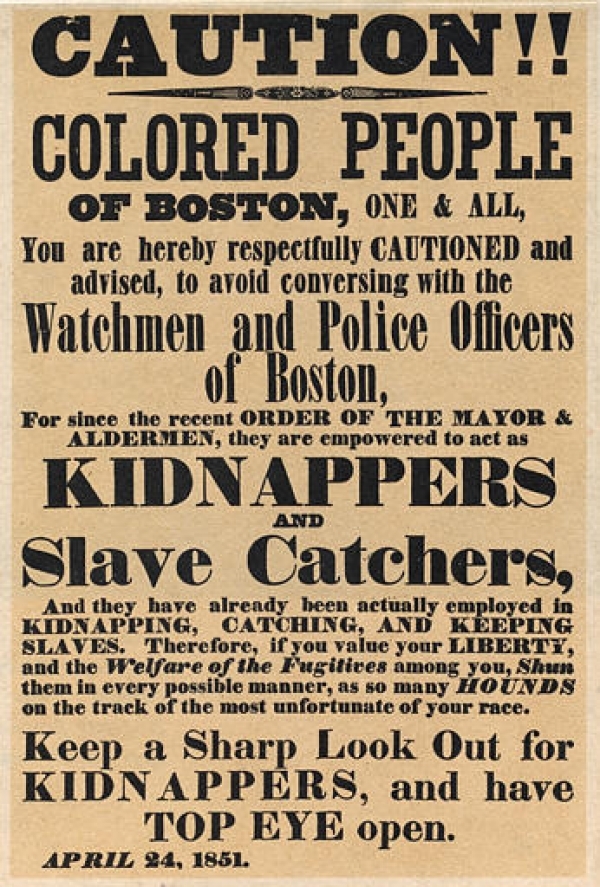

During the 1840's the arguments for and against slavery became more and more heated and a strong abolitionist movement had emerged in the North which had been busy organising the Underground Railway an escape route for runaway slaves and establishing safe havens for them in Northern cities.

In response to the activities of the abolitionist movement on 18 September 1850, the United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act that obliged Law Enforcement to identify and return runaway slaves at their owner’s request.

Edmund Ruffin opposed any attempt to change the Southerners right to own slaves which he saw as property and believed the abolitionists sought to impoverish the South and destroy their way of life. If the South wished to survive it must secede from the Union and he campaigned vigorously in his home State of Virginia for just such an outcome. By the 1850's the arguments over slavery had turned violent.

The Mason-Dixon Line was widely acknowledged as the marker on the map that divided North from South and no region north of that line could claim Statehood with slavery in place. Kansas, yet to be recognised as a State straddled this line and it was decided that before it could receive statehood the people resident must decide whether it should be free or slave.

This was a formula for chaos and the situation soon descended into violence as the Abolitionist Movement provided grants for anti-slavers to settle in the region whilst pro-slavers in neighbouring Missouri known as Border Ruffians invaded the territory with the intention of driving them out. "Bleeding Kansas", as it was shortly to become known erupted into open warfare and the situation was only calmed following Federal intervention and the threat to use troops to restore order.

On 16 October 1859, the abolitionist John Brown who had fought in Kansas, along with 21 followers, seized the Federal Armoury at Harper's Ferry, Virginia. He intended to capture the arms that would be required for a general slave insurrection. But no such insurrection occurred and two days later he was forced to surrender to troops led by Colonel Robert E Lee.

Despite the failure of his plan, to many Southerners this was all the proof they needed that Northerners intended to arm the slaves to murder them in their beds.

On 2 December 1859, John Brown was hanged, and Edmund Ruffin attended the execution where he was impressed by the calm with which Brown met his fate but he remained in no doubt that he deserved to die.

Discovering that Brown had been provided by supporters with pikes with which to arm the slaves he insisted on having one of them, and he was to carry it with him for the rest of his life. He also procured others and sent one to each Southern Senator with a letter explaining they were the weapons upon which Northern Abolitionists intended to impale Southern women and children.

Following John Brown's intervention Southern Secessionists at last found an audience and Ruffin, who had long despaired of the constant prevarication was spending more and more time in South Carolina, a hotbed of secession, where he could be guaranteed a more sympathetic audience as one of the growing number of "Fire Eaters" or those who demanded secession even at the expense of war. These, he would later say were the happiest days of his life.

On 20 December 1860, South Carolina became the first State to secede from the Union and over the next two months they were to be joined by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas. On 4 February 1861, the Confederate States of America was formed and Edmund Ruffin was delighted - his lifetime ambition had been achieved.

The recently elected Republican President, Abraham Lincoln, was determined that the Union would not be dissolved and that there could be no compromise on this issue. He would do his best to resolve the situation peacefully but if it came to war then so be it. The crisis was to come to a head in Charleston, South Carolina.

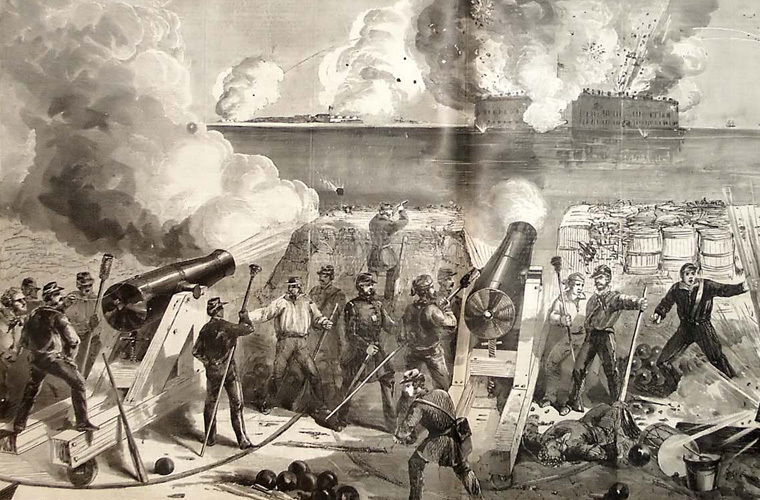

On 26 December 1860, Major Robert Anderson had removed his garrison of 127 men from the town and into Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbour. By March 1861, the newly independent State of South Carolina was demanding its evacuation, but President Lincoln ordered Anderson to remain where he was promising to both re-supply and reinforce him.

The clock was ticking, either Fort Sumter must fall or South Carolina's sovereignty and that of the recently formed Confederacy, would be fatally undermined.

On 11 April 1861, General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard in command in Charleston sent emissaries to Anderson demanding his surrender by 04.00 the following morning or he would order the shore batteries to open fire. Anderson did not respond but instead removed his troops to places of shelter within the fort.

On 12 April, Edmund Ruffin was summoned to the site of the city's coastal defences where in recognition of his many years’ service in the cause of Southern Independence he was granted the privilege of firing the first cannon at Fort Sumter. He was only too happy to oblige.

With the discharge of his cannon the American Civil War had begun, five days later his home State of Virginia also seceded from the Union.

On 21 July, the first major engagement of the war took place some 25 miles from Washington at Bull Run Creek also known as Manassas Junction. Despite his advanced age, he was 67, Ruffin was permitted to serve in a South Carolina Regiment in what would be a resounding Confederate victory. It seemed to Ruffin that he had fought in the decisive battle that would see Southern Independence become a reality and he was proud and honoured to have been a part of it - but it wasn't to be.

For the rest of the war Ruffin was to continue to write and exhort his fellow countrymen to ever greater effort and sacrifice but as the military campaign began to sour, casualties rose, shortages increased, and inflation soared the Fire Eaters became ever more marginalised.

In 1864, he returned to his plantation at Tidewater which had for a time been under Union occupation to find it partially destroyed, its crops untended, his slaves gone, and his house looted its walls covered in profane graffiti. The few Negroes who had remained were surly, uncooperative, and unwilling to work. His lifelong dream it seemed had become a nightmare.

On 9 April 1865, General Robert E Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia at Appomatox Courthouse and with Lee's surrender the Civil War effectively came to an end even though there were still other armies in the field and hostilities were to continue for several weeks.

As long as Confederates continued to fight then so would Edmund Ruffin and he contemplated travelling to Texas to participate in a guerrilla war, but the news just kept getting worse. On 26 April, the Army of Tennessee under General Joseph E Johnstone surrendered, on 10 May, the Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured, and on 26 May, General Kirby Smith surrendered his 43,000 troops, the last significant Confederate Army still under arms.

Earlier, on 13 May, the last engagement of the Civil War had been fought at Palmito Ranch in Texas. It had been a Confederate victory, but it was too late - for Edmund Ruffin it was all over.

On 17 June 1865, the 71-year-old Ruffin wrote these last words in his diary:

"And now with my last writing and utterances, with what will be my last breath, I here repeat and willingly proclaim my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule - to all political, social, and business connections with Yankees, and the perfidious, malignant, and vile Yankee race.”

Moments later he draped himself in the Confederate flag, placed the barrel of a rifle into his mouth, and blew his brains out. He had fired the first shot of the American Civil War. He may well have fired the last.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: