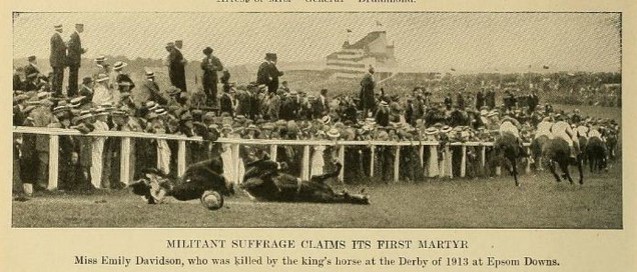

Emily Davison: The Derby Day Martyr

Posted on 19th June 2021

In many ways Emily Wilding Davison was to become the epitome of a Suffragette born as she was into a respectable suburban middle-class family in Blackheath, London on 11 October 1872. She was cosseted, educated and deeply frustrated by the lack of opportunities available to an ambitious young woman.

Her father, Charles Davison had died in 1893 and as a result Emily, who was studying for a degree at Royal Holloway College, was unable to graduate because her mother could no longer afford to pay the fees.

It was an early setback for Emily though she did eventually complete her studies and for a short time work as a teacher, but it was the social attitudes that prevailed in Edwardian Britain not family misfortune that were to prove the most difficult to overcome.

Women were perceived to be and treated as second-class citizens, and it was only as recently as the 1882 Amendment to the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act that women had been recognised as entities separate and not subordinate to their husbands. Even so divorce from a violent or abusive spouse remained a difficult and humiliating process.

Such inequalities permeated much of society and the notion of the woman independent of a man remained far off. There had been advancements of course, and women could be found working as nurses and as teachers and were even permitted to study at Oxford and Cambridge Universities, though they were forbidden from graduating.

Work of the more menial kind whether in domestic service or elsewhere remained available as was the fulfilment of more traditional roles but the professions remained strictly off-limits but the most glaring omission of all was that they were not permitted a say in the making of the law or a vote in national elections.

On 10 October 1903, the Women’s Social and Political Union or W.S.P.U was formed by six women meeting in a suburban house in Manchester. Among them were Emmeline Pankhurst who along with her daughter Christabel would soon assume the new organisations leadership.

It was not the first Women’s Suffrage Movement as six years earlier in 1897 Millicent Fawcett had formed the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies or N.U.W.S. S. Its policy was to achieve female suffrage by democratic means, and it perhaps more truly reflected the views of women than the always smaller and more militant W.S.P.U.

The W.S.P.U launched their campaign for social reform and women’s suffrage in conjunction with the recently formed Independent Labour Party and frustrated at the intransigence encountered by the N.U.W.S.S they were determined to adopt a more direct approach.

They lobbied individual MP’s often in the most strident of tones, harassed Ministers on their own doorstep and organised petitions but even they could little have imagined just how steadfast the opposition to female suffrage would be and the Government’s refusal to even debate the issue saw their campaign turn violent. But by adopting direct action as a tactic, they played into the hands of those opposed to female suffrage who argued that women were too emotional and unstable to be trusted in matters of great importance such as the formation of governments.

TThe Suffragettes as they were soon to become known did not behave as women were expected to, they marched through city centres, protested outside town halls, disrupted political meetings and even chained themselves to the railings outside Buckingham Palace; and the more the Government ignored them the more radical they became ceasing merely to disturb the peace instead committing overtly criminal acts. They smashed shop windows in Oxford Street, dug up golf courses and committed many acts of arson including the torching of post boxes. A particular target was Church property, the Church being a leading advocate of continued female disenfranchisement. They even physically assaulted leading politicians behaving as one journalist put it like ‘feral beasts.’

Increasing numbers of women were being arrested and imprisoned and in response the more dedicated among them would often go on hunger strike. This provided the Authorities with a dilemma for they could not afford the spectacle of women from respectable backgrounds starving themselves to death under their watch, but neither could the law be seen to buckle before intimidation so any female prisoner who refused to eat would be force fed.

This was a painful and humiliating process with the woman being held or tied down and either a nasal tube would be inserted, or the mouth would be forced open with a steel or wooden gag and a tube thrust down the throat. Liquid nutrients would then be poured in.

The nurses present would then sprinkle scent about the place to disguise the smell of the constant vomiting.

Once the process involved in force-feeding began to circulate and become public knowledge this too became an embarrassment for the Government and so a new way had to be found. In 1913, Parliament passed the Cat and Mouse Act:

Those Suffragettes who were arrested and consequently chose to go on hunger strike would be permitted to do so. However, once sufficiently weak from a lack of sustenance for it to prove a risk to their health they were released on licence. It was assumed that once they were home with their families, they would start eating again which they invariably did. If they then went on to break the terms and conditions of their licence then they would be rearrested and the whole process would begin again.

Emily Davison was undoubtedly one of the more militant of the Suffragettes:

A strikingly tall, thin-faced and slender woman with red hair, green eyes and a permanent half-mocking smirk that made her stand out in a crowd she had joined the W.S.P.U in 1906 and was aggressive in her manner from the outset. Her personal motto was, ‘rebellion against tyrants is obedience to God,’ and she took it literally.

Humourless and quick tempered she would labour the point on any issue and was never held in any great affection by her colleagues but her devotion to the cause was never in doubt.

In October 1909, she was jailed for a month for stone throwing and a year later in November 1910 she was jailed for another month for smashing windows at the House of Commons. On 2 April 1911, she hid overnight in a cupboard at the Palace of Westminster thereby trying to force the National Census to give it as her official address.

In January 1912, she was imprisoned for 6 months for setting light to mailboxes and in November of the same year was again jailed for 13 days for assaulting a vicar she mistook to be the Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George. She would later plant the bomb that partially destroyed his recently purchased house in the country.

Emily was no less obstreperous whilst in prison and during one of her many periods of confinement she went on hunger strike and force fed responded by barricading herself in her cell and was only forced out when the Prison Authorities flooded it with freezing cold water.

Fanatical to the point of unreasonableness it seemed there were few outrages that Emily would not be willing to perform to achieve female equality particularly if they garnered publicity for the cause and June 4, 1913, was Derby Day:

The horse race was one of the biggest events on the summer social calendar and not only would thousands of the public be in attendance but so also would, be the great and the good of British society including the King and Queen. Emily knew this and so she would be in attendance too.

It is unlikely that when Emily arrived at Epsom Downs on that bright summer day, she did so with the intention of becoming a martyr. She had not told anyone that she was attending the race and she had on her person a W.S.P.U banner and rosette, a race-card, and a return train ticket. Rather, it seems likely that knowing the race would be shown in cinemas the length and breadth of the country she merely intended to pin the rosette to the bridle of the King’s horse Anmer as it passed by - to do so would be a great propaganda coup.

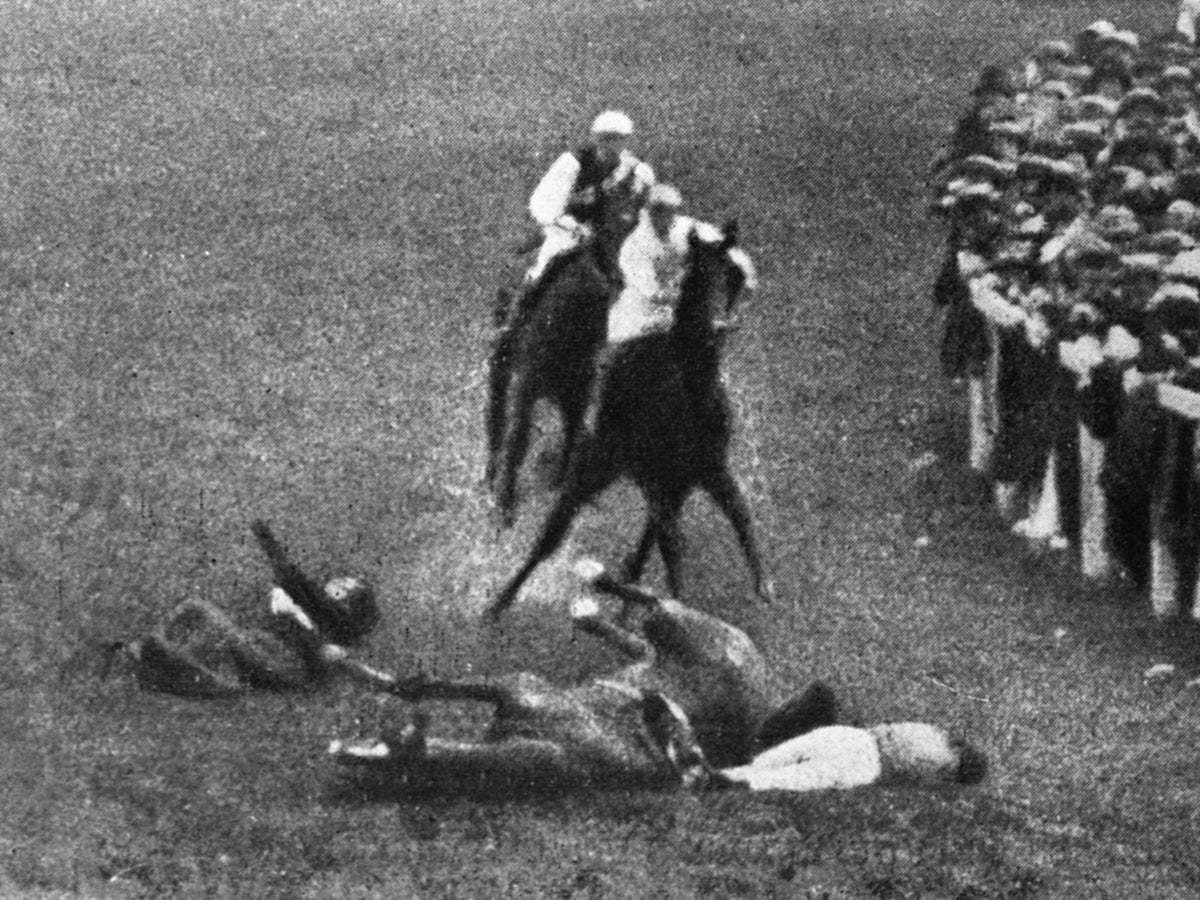

As Anmer came around Tattenham Corner and into the straight it was lying in second from last place and most of the other horses had already passed so most people’s focus was elsewhere. Even so, as Emily was about to dip under the rails a man noticed and tried to stop her but she struggled free shouting as she did so – No, I will.

As Emily stepped out in front of the horse, she may have expected it to rear up or veer away but it did neither and as she went to grab the bridle it ploughed straight into her trampling her underfoot causing the horse and its jockey, Edward Jones to crash violently to the ground. Emily was taken to hospital where great efforts were made to revive her but she never regained consciousness and died four days later.

The country was appalled and outraged but not at Emily’s fate, but rather at what she had done. There was little sympathy for her either in the press or among the public generally. She was considered a fanatic, another example of an emotionally unstable woman. Far more attention was given to the condition of the horse and its jockey.

Anmer, despite falling heavily survived and would race again but Edward Jones who suffered a slight concussion was traumatised and would later say how the face of that woman haunted him every day of his life. He wrote a letter of condolence and sent a wreath to her funeral – 38 years later he would take his own life.

Emily Davison’s funeral procession took place in London on 14 June 1913 and was a propaganda coup for the Suffragette Movement. It became the occasion for a massive rally, thousands line the route of the cortege, and a banner was draped across her coffin with the slogan “Deeds not Words.” She was buried in a more sedate ceremony in Morpeth the following day.

Emily’s sacrifice made little immediate impact other than to reinforce the prevailing prejudice against women being trusted with making decisions of any great importance.

It seemed that for all the many years of argument, the criminal acts, the violence and Emily’s own sacrifice women were no nearer getting the vote than they had been when the campaign began.

It would take four more years of social dislocation and war for women to get the vote and even then, it would be qualified. In 1918 the House of Commons passed the Representation of the People Act by 385 votes to 55 but only extended the franchise to women 30 years of age or over. Ten years later in 1928 the Equal Franchise Act gave the vote to all men and women aged 21 or over and without any property qualification.

Would this have been achieved without the sacrifice of Emily Davison? Yes, it would,

Share this post: