Emperor Hadrian

Posted on 12th June 2021

Hadrian was the first Emperor of Rome to acknowledge that there were limits to is territorial conquests first shoring up its borders and then bringing an end to further expansion, the most famous example of which is Hadrian’s Wall in England, the 73 mile long fortification which stretched from the River Tyne to the Solway Firth and marked the northern limit of the Roman Empire.

The future Emperor Hadrian was born Publius Aelius Hadrianus on 24 January AD 76, in Italica near modern day Seville in Spain. He came from a well-established but decidedly provincial family that had little direct contact with Rome, but he was a distant cousin on his mother’s side of the future Emperor Trajan.

Both of Hadrian’s parents died when he was aged 10, and as Trajan was his nearest male relative, he became his ward travelling to Rome for the first time some four years later in AD 80.

At the time of Hadrian’s first visit to Rome his cousin Trajan was a successful Army General but in October AD 96 had been adopted by the childless and unpopular Emperor Nerva to curry favour with the army and secure his own position. When he died on 27 January AD 98, just two years into his reign, Trajan succeeded him.

Over the years Trajan was to become increasingly reliant upon Hadrian’s support but even so never adopted him as his son or formally named him as his successor. Even so, he worked hard and accompanying the Emperor on his military campaigns rose rapidly through the ranks of both the military and the Imperial Administration earning a reputation as an able and trusted politician and adviser; but accrued little kudos as a result and it was only persistence and the support of Trajan’s wife, Pompeia Plotina that he was to place himself in the line of succession.

It was said that as Trajan lay dying, he at last adopted Hadrian as his son and designated heir but the document of succession that resulted was not signed by the Emperor but by his wife. Nevertheless, when Pompeia Plotina delivered the clearly falsified document to the Senate, they accepted it without protest.

At the time of Trajan’s death on 9 August AD 117, Hadrian was serving as Governor of Syria and did not return to Rome immediately but instead appointed Publius Acilius Attianus, who had been his co-guardian along with Trajan and would be his future Prefect of the Praetorian Guard, to rule in his absence. He believed that his absence would provide the opportunity to flush out those in Rome who might oppose his succession, and he was right.

Not long after Attianus informed Hadrian that he had uncovered a plot against him, and he demanded the Senate order the execution of the conspirators without recourse to a trial. Fearing the worst, they reluctantly complied. But such ruthless and arbitrary use of power was not to be indicative of Hadrian’s reign.

His first major policy decision was to curb any future expansion of the Empire.

The continued acquisition of vast territories, often wastelands of little commercial value that had to be governed, administered and policed was proving ruinously expensive. His own experience of war had convinced him that Rome was becoming dangerously overstretched. Much of its army was now made up of foreign troops recruited from the provinces and conquered territories whilst its enemies, particularly in the East, were becoming increasingly more powerful and better organised.

Instead of going to war with Rome’s enemies he now made peace treaties with them, and he built fortifications that marked the boundaries of the Empire such as Hadrian’s Wall in Britain and the wooden forts that lined the eastern banks of the Rhine. In the meantime, Roman troops were withdrawn to the Euphrates and west of the River Danube where the only bridge spanning it was destroyed. But this was a dangerous strategy, and Hadrian knew it.

To forego the prospect of further conquest not only restricted the opportunity for glory of the ambitious but deprived the common soldier of valuable booty. He had to secure his support within the army and to do so he would not only prove he was one of them, but the best of them.

Visiting the Army on the Rhine he determined to keep them occupied ordering them to remain on alert and training them relentlessly. He also forewent Imperial grandeur to live the life of the ordinary soldier dressing simply, eating alfresco and sleeping out at night.

A physically imposing man tall and broad shouldered the troops admired and respected their new Emperor who as an avid hunter possessed extraordinary powers of endurance which he showed off by besting his troops in training. He also remained careful to reward them whenever possible.

But despite his many years in the military, Hadrian never really considered himself, a soldier but rather as a scholarly man, a man of culture. He loved Greek architecture, literature, philosophy and was an enthusiastic poet who grew a full beard and wore it in the Greek style. This despite the fact Romans prided themselves on being clean-shaven to distinguish themselves from the Barbarians. He also enjoyed nothing more than indulging in philosophic debate with the leading academics of his day though he was not a man to be argued with:

“Although he was adept at prose and at verse and very accomplished in all the arts, he used to subject the teachers in these arts to ridicule, scorn, and humiliation.”

Those who were invited to his scholarly soirees were wary of his temper. When the philosopher Favarinus yielded to the Emperor on a minor linguistic point even though he was right his colleagues criticised him for doing so. In response he said:

“You are urging the wrong course my friends when you do not allow me to regard the most learned of men the one who has thirty legions.”

Hadrian was married to Vibia Sabina but he was homosexual and showed little interest in her either physically or emotionally and though she was to accompany him on his many journeys throughout the Empire the marriage was never a happy one. Indeed, she was to say that she would never have children by her husband because as “monsters they would harm the human race.”

Vibia Sabine would never forgive her husband for being in love with a 19 year old Greek youth named Antinous whom he constantly referred to as his beautiful boy, and although he never flaunted his homosexuality he took no steps to conceal it either. Affection between the men was displayed openly and Antinous was his constant companion.

In AD 130, Hadrian embarked upon an artistic tour of the Eastern Provinces. He visited Greece before moving onto Egypt where on a journey down the River Nile Antinous tumbled from the boat, got caught in reeds and drowned.

Hadrian who was so devastated and grief stricken it was said that he wept like a woman in floods of tears proceeded to build temples in Antinous’s honour, found cities in his name and even had him deified as a God but it did little to assuage his pain and in the years following the loss of his great love, he became an increasingly bitter and vindictive man. He did not return to Rome however but continued on to the province of Judea.

Having taken a guided tour of the ruins of Jerusalem which had been destroyed during the First Roman-Jewish War of AD 66-73 he decided it should be rebuilt as a Greco-Roman city.

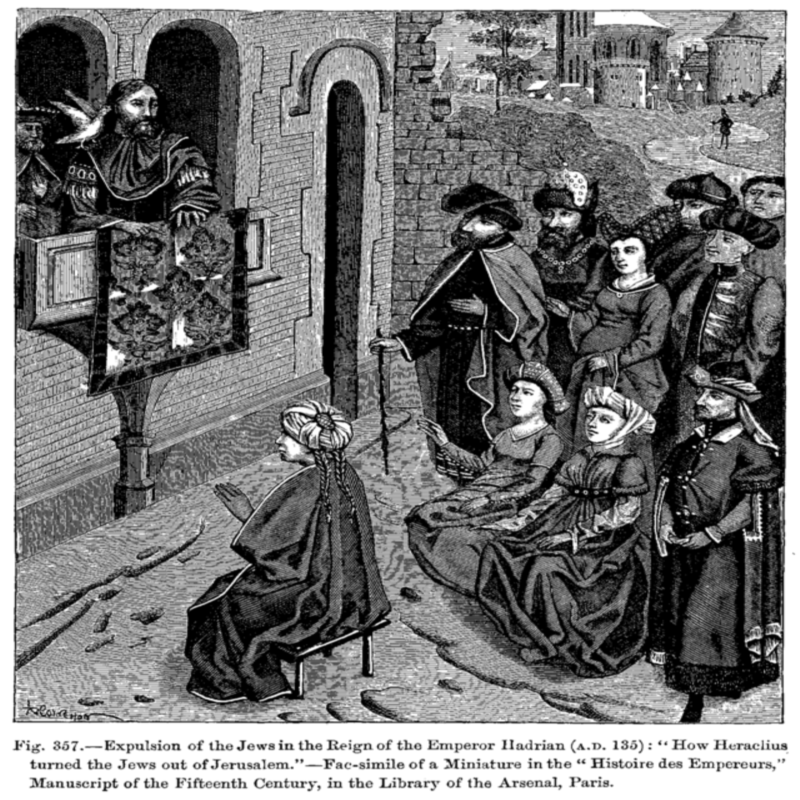

He constructed a large temple to the Goddess Venus on the site that would later be venerated as the Tomb of Christ and rebuilt by the Emperor Constantine as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; and demolished all the remaining Holy Jewish Sites building instead temples to the Roman Gods across the city. He then abolished the ritual of circumcision which he considered a barbaric act of mutilation, banned Jews from living within the confines of the city, and renamed it Aelia Capitolina.

Having spent his reign assiduously avoiding conflict Hadrian now brutally trampled upon Jewish sensitivities to the point where a violent reaction became inevitable but when Judea rose in open revolt astonishingly the Romans were taken completely by surprise.

Unlike the earlier rebellion against Roman rule when three separate Jewish armies were still fighting one another for control of Temple Mount as the Romans advanced through the streets of Jerusalem towards them, they were united and organised.

The XXII Legion was ambushed and routed while others were badly mauled as under the leadership of Simon bar Kokhbar and Akiba ben Joseph the Jews out-manoeuvred and out-fought the Romans who badly shaken were forced to abandon Judea altogether.

In some desperation Hadrian had been forced to call upon reinforcements from across the Empire and had ordered his leading General, Sextus Julius Severus to return from Britain to take command.

Rather than confront the Jewish forces in open battle he adopted a scorched earth policy destroying crops and slaughtering livestock, and some 50 fortified towns and 985 villages were raised to the ground and the population forced to flee with those who failed to do so in time killed without exception. Finally in AD 135, after a year of bitter warfare the will of the Jewish people was broken.

After losing control of Jerusalem, Simon bar Kokhbar withdrew what remained of his army and a number of refugees to the fortress of Betar. When it to fell to Roman assault shortly after all within were killed and as vengeful in victory as they were determined in defeat, they were not to permit the Jews to bury the bones of the dead in Betar for seventeen years.

In the aftermath of the Jewish revolt, Hadrian was also to prove himself as ruthless as any Emperor before.

It has been estimated that as many as 500,000 Jews were killed during the rebellion, some in the fighting but most slaughtered at its end. But this was not considered punishment enough and tens of thousands more were sold into slavery while his persecution of those Jews who remained also proved relentless: the Judaic Calendar was abolished, the preaching of the Torah prohibited, and the Judaic Scholars rounded up and executed. The Sacred Scroll was ceremonially burned on the Temple Mount as the Jewish population was forced to look on, and the Province of Judea was renamed Syria Palestina. Jews were also banned from entering Jerusalem and from practising their own religion. Even today when Jews mention the name of Hadrian the sentence will often end with the words, “may his bones be, crushed.”

For Hadrian however his suppression of the Jewish revolt was a pyrrhic victory with his legions having been humiliated and his peace policy undermined. He took no pleasure in it and declined his right to have a Triumph through the streets of Rome.

In his final years Hadrian was a lonely man caught in a loveless marriage, with no children, and never having fully recovered from the loss of his beloved Antinous, he spent much of his time alone in quiet reflection, reading and writing poetry.

He died on 10 July AD 138, aged 62, after a protracted illness that had often left him bedridden it being said that he simply stopped breathing after his heart gave out – his broken heart.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: