Empress Elisabeth (Sisi): Another Habsburg Tragedy

Posted on 31st January 2021

Considered one of the most beautiful women of her age Elisabeth Amalie Eugenie, Empress of Austria-Hungary, known as Sisi, was born in Bavaria on 24 December 1837, the second daughter of the eccentric Duke Maximilien and the distant and aloof Princess Ludovika.

With their father often away pursuing his obsession with the circus and their mother taking little or no interest in them the children were allowed to roam free with the energetic Sisi often neglecting her studies for horse riding, sports and long walks in the country. She also began a life-long friendship with her cousin the future Mad King Ludwig of Bavaria with whom she indulged her love of fairy tales and opera. But her greatest love, her obsession, was herself.

Her carefree lifestyle was to be abruptly curtailed however, when in the summer of 1853 her aunt the Archduchess Sophie visited Possenhoffen Castle with her 23-year-old son Franz Joseph, the Emperor of Austria-Hungary. It was the Archduchess Sophie’s intention to find a bride for her bachelor son and she had set her gaze upon Elisabeth’s older sister Helene but when they met Franz Joseph was not impressed by his intended who he found to be lifeless and dull. Elisabeth was another matter however, she was pretty and vivacious if a little shy, but in a coy manner that only added to her attractiveness. He told his mother, "I will not marry Helene, but I will marry Elisabeth."

The Archduchess Sophie, who considered Sisi a rather silly young woman tried to dissuade her son, but he remained adamant. She made it plain she thought it a mistake but just wanting her son married and with an heir in the end relented and by the time they departed five days later Franz Joseph, and the 15-year-old Elisabeth were engaged.

On 24 April 1854, the two cousins were wed but it was never a happy marriage

On their wedding night Sisi who had been taught nothing of sex was so traumatised by her husband’s advances that she locked herself in her bedchamber refusing to emerge or speak to him again for three days. Yet despite the initial distress caused by the intimacy of the marriage bed Elisabeth was soon pregnant and on 5 March 1855, she gave birth to a daughter. She was however, through no fault of her own to be an absent mother as the baby was removed from her care by the always domineering Archduchess who then proceeded to name it after herself. When she gave birth to a second daughter the following year it was similarly taken away.

Elisabeth soon began to feel isolated at an Imperial Court so different to the informality of her childhood home with its strict protocols and rigid formality which saw attendance at dinner by invitation only and where written permission had to be sought merely to take a carriage ride. She was also not shy in expressing liberal views that were not widely shared especially within the environs of the Hofburg Palace and was frowned upon for not only meddling in politics but for being a woman and having the temerity to do so.

The early years were particularly difficult, her husband bored her, and she was subject to the whims of her mother-in-law who sought to dictate every aspect of her life. Moreover, despite having proved her fecundity she had still not produced a male heir. Not long after giving birth to her second daughter she returned to her room to find a book opened on her desk with the following words:

The natural destiny of a Queen is to give an heir to the throne. If the Queen is so fortunate as to provide the State with a Crown-Prince this should be the end of her ambition, she should by no means meddle with the government of an Empire, the care of which is not a task for women... If the Queen bears no sons, she is merely a foreigner in the State, and a very dangerous foreigner, too. For as she can never hope to be looked on kindly here and must always expect to be sent back whence she came, so will she always seek to win the King by other than natural means; she will struggle for position and power by intrigue and the sowing of discord, to the mischief of the King, the nation, and the Empire.

Elisabeth was in no doubt that the Archduchess Sophie had been responsible, and it did little to lighten her mood.

Coming from a family, the Wittelsbachs who had a deep strain of non-conformity, some might say insanity, her inherited eccentricities required an outlet; but in the confines of an Imperial Court that stifled all emotional and intellectual expression no such thing existed. As a result, she became increasingly withdrawn and her failing health imagined as much as real reflected her deep unhappiness. Suffering from migraines and stomach pains she took solace in the preservation of her beauty, a process that came to dominate her life.

Determined to maintain her figure she exercised obsessively and would often starve herself for days on end so that even at 5’8 tall she never weighed more than 7st 12Ibs. Her staple diet was soup and eggs washed down with milk though it was reported that on occasion she would binge, eating meat and drinking champagne to excess.

Despite her already lean appearance she disavowed underclothes believing they distorted the wasp-like waist of which she was so proud and would instead wear a leather corset so tight that she would often have it sewn into her clothes to accentuate her slender figure even further. Her rooms she had adorned with full-length mirrors in which she could check her posture from every conceivable angle.

Her grooming regimen was equally as rigorous relentless:

She would take a cold bath every morning believing that it helped to tighten and tone the skin, steam baths for weight loss, and a warm bath every evening later to soften and make it glow. Her waist length hair was set every morning taking many hours during which, making the most of her time, she would have a tutor in attendance to school her in languages or any other subject that may have taken her fancy.

Franz Joseph remained deeply in love with his beautiful wife even if it wasn't a love affection shared. Not that Elisabeth disliked her husband she simply found him dull - he liked to hunt wild boar when she was interested in ideas. She would discuss politics with him at the dinner table and tried to influence him in affairs of state which appalled his advisors who reported it to the Archduchess, and though Franz Joseph would listen attentively to his wife it was his mother’s advice he heeded. As a result, Elisabeth became even more isolated but on 21 August 1858, she gave birth to a son and heir they named Rudolf, she had at last done her duty.

Rudolf was to be his mother’s son and he was to share not only her unconventional views but also her often irrational behaviour infuriating his father with his liberalism and outraging the Imperial Court with his libertine lifestyle.

As the only person who seemed able to reason with him Rudolf became the means by which Elisabeth could assert herself, he was her conduit of expression she the conciliator of his mood. Although, he was to prove a constant concern and be the cause of many a sleepless night he was the child she could relate to and express a love for so long subdued.

As the years passed Elisabeth became increasingly estranged from the Imperial Court and her almost constant state of malady saw her retreat to the country sometimes for months on end. During these periods of self-imposed exile Elisabeth devoted herself to issues she believed mattered, her health, her looks, and the common people she declared a love for but showed no interest in associating with. She spoke in favour of good causes, helped financially when she could, and bequeathed large sums of money to charitable organisations in her Will.

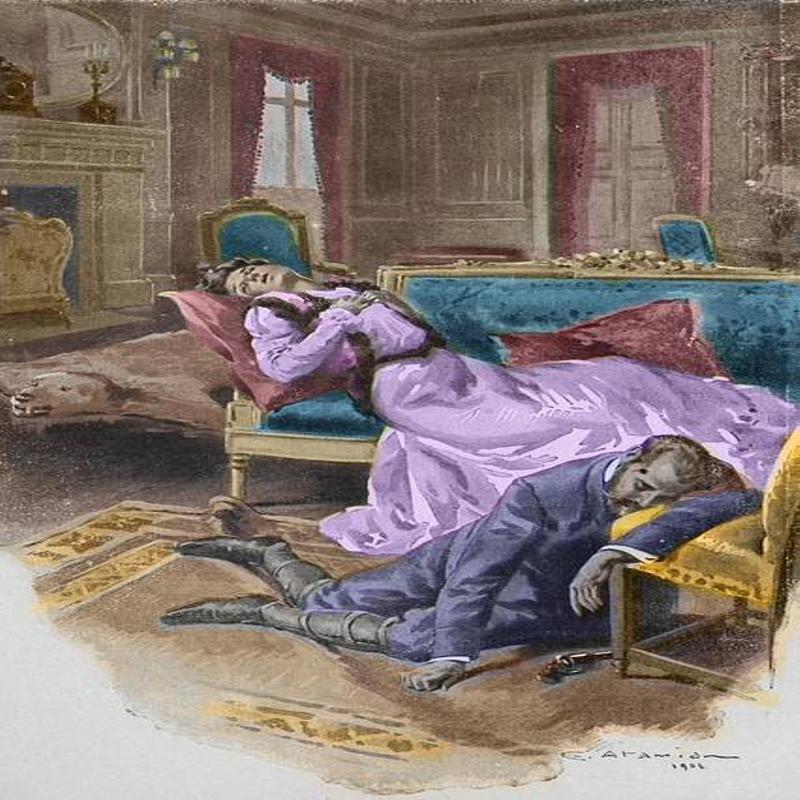

But tragedy always lurked in the shadow of the Hofburg and on 31 January 1889, Elisabeth received the news that the always unstable Rudolf and his young lover, Mary Vetsera had been found dead at the Mayerling Hunting Lodge in what appeared to have been a bizarre suicide pact. It had been Rudolf who infused his mother with a confidence she had previously lacked, and which saw her become a public figure appearing regularly in newspapers and magazines as one of the most talked about women in the world. Now overwhelmed with grief she descended into a deep melancholia from which it was said she never truly recovered.

Elisabeth had already taken to travelling abroad before Rudolf’s death now she did so more than ever rarely seeing the emperor and her other children.

Concerned at the prospect of ageing her exercise regime became ever more rigorous and her diet even stricter and she began to wear high-neck dresses and carry a parasol to conceal her face - time is rarely kind.

In the summer of 1898, a gaunt and thin but still graceful and not unattractive Empress Elisabeth travelled incognito to Switzerland with a small entourage and her lady-in-waiting Countess Irma de Sztara Nagymihali. In the early afternoon of 10 September, unaware that their identity had been revealed in the newspapers the previous day, Elisabeth accompanied by the countess were strolling along the shore of Lake Geneva on their way to catch a boat when a man suddenly appeared before the Empress pushed aside her parasol and appeared to grab her. He said nothing and soon ran off, and the Empress though somewhat shaken seemed otherwise unhurt.

The countess wanted to return to the hotel but Elisabeth insisted they proceed to their destination but they hadn’t walked far when the Empress began to lose her balance and the Countess had to take her arm.

With the colour draining from her cheeks and her breathing already heavy and deep the countess suggested they rest awhile but Elisabeth was adamant they continue. But she was right to be concerned as no sooner had they boarded the boat than Elisabeth lost consciousness and collapsed. A distraught Countess demanded that the captain attend to her at once but sworn to secrecy she was loath to reveal the Empresses true identity and it wasn’t until she did so that a doctor was sent for but vital time had been lost.

As they unlaced Elisabeth’s corsets to ease her breathing a small wound gently oozing blood was discovered beneath her left breast and with some urgency she was carried to a cabin and laid upon a bed but before she could be treated, she took two deep breaths and died.

The Empress of Austria-Hungary had been killed by a single wound made with a sharpened 4-inch nail file that had punctured her lung wielded by the Italian anarchist Luigi Luccheni.

It was yet another Hapsburg Tragedy.

Share this post: