Erwin Rommel: The Desert Fox

Posted on 3rd July 2021

By January 1942, the war in the Western Desert was not going well for the Allies, so much so that the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill chastened by failure felt compelled to address the House of Commons thus:

We have a very skilful and daring opponent against us, and may I say across the havoc of war, a very great General – what else matters than beating him?

It is unusual for an enemy to be praised in the midst of a conflict but then Erwin Rommel was that rarity in war, a hero to both sides – but why?

As a soldier of audacity and daring he would fight as he put it a ‘war without hate’ who in a conflict of unparalleled brutality toward combatant and civilian alike victory on the battlefield remained his one and only priority.

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel was born in the town of Heidenheim in southern Germany on 15 November 1891, the son of a schoolteacher who though he had served in the army, compulsory at the time, was not a military man; but in a Germany, which had only existed as a unified nation since 1871 and remained very much an extension of Prussia, a place that Voltaire had described as an army with a state, the military enjoyed an elevated status and so becoming a soldier was considered a good career move.

In 1909, aged 18, he enlisted in the 124th Infantry Regiment soon after enrolling For Officer Cadet Training School in Danzig. Commissioned 2nd Lieutenant in January 1912, the young Rommel was excited to be a soldier and like many others greeted the declaration of war in August 1914 with enthusiasm. Here was the opportunity to put what he had learned into action, and of course it would all be over by Christmas.

The early months of the war on the Western Front was one of mobility and manoeuvre where the opportunity to display initiative remained and Rommel, a Platoon Commander, took full advantage undertaking a series of daring flanking attacks which penetrating far beyond the enemy front-line brought him considerable success. He was promoted to 1st Lieutenant and awarded the Iron Cross Second Class for his belligerence and courage in seeking out and attacking the enemy, something that would soon become his standard modus operandi often bewildering both enemy and ally alike.

In September 1914, the German plan to bring France quickly to heel was thwarted on the River Marne and the Western Front quickly descended into stagnant trench warfare and Rommel, much to his relief, was transferred East where joining the Alpenkorps he continued to impress his superiors in the campaign against Rumania but it was to be in Italy on the Isonzo Front that he was to make his name.

On 24 October 1917, a combined German/Austro-Hungarian Force launched a massive assault on the Italian 2nd Army in and around the small town of Caporetto. The Italians who had been relentlessly attacking the Austro-Hungarian positions on the River Isonzo for more than two years were taken completely by surprise, and though the flanks of their army held firm against the Austrians the centre of the line where the Germans spearheaded the attack simply collapsed.

Utilising recently developed infiltration tactics that saw specially trained Storm-trooper Units armed with grenades and flame throwers advance ahead of the main army the confusion they sowed was absolute and huge gaps in the line soon appeared as Italian resistance melted away.

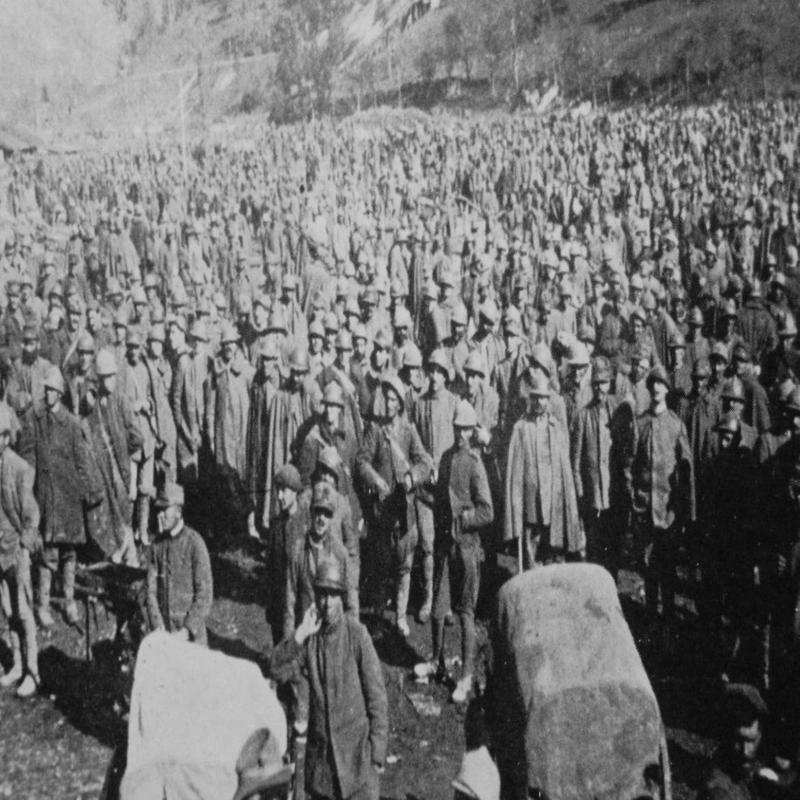

Even without these new tactics the mere sight of Germans on the horizon was often enough to cause the Italians to panic, desert their posts and surrender in droves. This was warfare to Rommel’s liking and as the Italian centre crumbled, he took full advantage. In a little over two days of fighting near Mount Matajur his company of just 150 men captured more than 9,000 Italians and 81 guns for the loss of just 6 men killed and 30 wounded; again, when he assaulted the town of Langarone he took a further 10,000 Italians prisoners with barely a shot being fired. But such was the speed of the German advance (15 miles on the first day alone) they soon outstripped their lines of supply and communication and were further hampered by the vast amounts of materiel and prisoners taken, more 275,000 men in just a few weeks.

Reinforced by 11 French and British Divisions hastily despatched from the Western Front some 120,000 men in total, the Italians after a long and humiliating retreat finally regrouped and established a new line on the River Piave, a mere 15 miles north of Venice.

The assault at Caporetto would eventually peter out but regardless of its failure to knock Italy out of the war, Rommel, an ambitious career soldier was delighted with his personal contribution as also were his superiors who awarded him the Pour le Merite for his actions at Matajur. He was also promoted to Captain and transferred to the General Staff.

But his experiences at Caporetto left him with a life-long disdain for Italian soldiery, their willingness to surrender without a fight and then unashamedly fraternise with their captors left him bewildered, even embarrassed. In the Desert War to come his barely disguised contempt for the Italians who were now his ally would have serious consequences as he became over-reliant on the scant manpower and resources of the Afrika Korps.

Rommel, who had earlier married 17-year-old Lucia Maria Mollin while on leave in Danzig despite having already fathered a child by another woman, remained in the much reduced German Army at the end of the war. Here he shared with many of his fellow Officers his bemusement that a conflict in which he had experienced only victory had ended in such abject defeat since when the Germany he loved had been plunged into chaos and revolution.

By October 1920, he was in Stuttgart where as a Company Commander he helped quell civil unrest acting with moderation where others had been brutal. It was not work to his liking, he had never been interested in politics and where some relished the opportunity to crush the ‘Reds’ he baulked somewhat at inflicting violence on his fellow countrymen.

Promoted to Major, in 1929 he was appointed an instructor at the Military Academy in Dresden where with more time on his hands he wrote ‘Infantry Tactics’, am account of his experiences in the Great War and of the lessons learned with his strong advocacy of the offensive, of infiltration, of rapid deployment and swift and decisive action bringing him to the attention of another former soldier Adolf Hitler who possessed his own much-thumbed copy.

The admiration was mutual, and Rommel was to display an almost child-like devotion to the person of the Fuhrer often writing in the most glowing terms to his wife Lucie of the man who had been sent by Providence to rescue Germany from the abyss: "He (Hitler) has been called by God to lead the German people up to the sun. He radiates a magnetic, hypnotic power."

When in January 1933, Hitler became Chancellor he wrote: “What a stroke of luck for Germany.” And in November 1938, following a failed assassination attempt: "It has only strengthened his will. It is a joy to see. The idea that it could have succeeded doesn’t bare thinking about."

Promoted to Colonel, Rommel was serving as Head of the Military Academy at Wiener when in October 1938, at Hitler’s personal request he was appointed to command the Fuhrer’s Escort Battalion.

To be charged with the protection of the Fuhrer, the man who had re-occupied the Rhineland, achieved Anschluss with Austria, annexed the Sudentenland and had not just expanded Germany’s borders but restored her pride, achievements some said surpassed even those of Bismarck, was a very great honour indeed – now he was able to observe the great man at close quarters.

BBut being responsible for the personal safety of the Fuhrer was to prove an impediment to ambition when in September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Deeply frustrated by his inability to participate in the campaign he was determined not to miss out on the looming conflict in the West and he used his relationship with Hitler to lobby hard for the command of a Panzer Division.

He had no experience of armoured warfare and had never commanded beyond Battalion level and many of his colleagues were angered by his manipulation of the Fuhrer to secure a command over those who were better qualified to do so, particularly when he declined the opportunity to lead an Infantry Division.

His loyalty to the Fuhrer was to be rewarded however, and in February 1940 he was given command of the 7th Armoured Division.

The now General Erwin Rommel, whose last task had been to organise the victory parade through the streets of Warsaw now had command of an army, and a formidable army it was: 218 tanks, 2 Regiments of Infantry, a Motorcycle Battalion, a Battalion of Engineers and an anti-Tank Regiment. But could he lead it effectively?

On 10 May 1940, the German Army invaded the Low Countries but as the French Army and the British Expeditionary Force advanced into Belgium to meet the perceived threat the main thrust of the German attack, circumventing the Maginot Line defences, came through the heavily forested Ardennes Region of Eastern France.

Believing the Ardennes to be impassable to mechanised transport the French had subordinated it to a secondary front and left it weakly defended and so meeting little resistance the Armoured Divisions under the overall command of General Heinz Guderian made rapid progress and in the vanguard of the attack was Erwin Rommel and 7th Panzer.

Racing ahead at such breakneck speed that they were soon across the River Meuse and advancing on Sedan it was often difficult for his superiors to determine exactly where Rommel was and the 7th Panzer soon earned the nickname the Ghost Division – it was not necessarily a compliment.

Meeting little resistance on 17 May he took 10,000 prisoners for the loss of just 36 men – it was Caporetto all over again.

But Rommel worried his superiors as much as he impressed his subordinates. They believed his determination to maintain the momentum and not wait for infantry support left him vulnerable and that without proper reconnaissance he could be heading into a trap. Indeed, his haste could have contributed to Hitler’s notorious Halt Order of 24th May that provided the invaluable breathing space the British needed to evacuate its Expeditionary Force from the beaches of Dunkirk. He wasn’t permitted to resume his advance until 5 June and the implementation of Case Red, the second phase of the conquest of France.

Although resistance on the ground stiffened any fears of greater resolve among the French High Command were soon dispelled as the Panzers continued much as before cutting a swathe through the French countryside and often advancing as much as 50 miles a day.

By 10 June, 7th Panzer had reached the coast at Dieppe from where Rommel was ordered to advance of Cherbourg which surrendered just three days before the Armistice was signed on 22 June.

Yet again Rommel had enjoyed a good war and Hitler’s favourite General had proved himself worthy of the faith placed in him but not without criticism – it was said he was impatient, often more reckless than daring, did not always see the bigger picture and displayed an ad hoc attitude to orders.

Some also considered his evident self-confidence to be little more than arrogance on his part and often ill-founded. Indeed, there would always be an element of mistrust even among those who were his admirers. But his cavalier spirit would prove propaganda gold.

On 10 June 1940 to the cheers of the thousands of his black shirted supporters gathered in the Square below Benito Mussolini, II Duce, declared war on Britain and France from the balcony of the Palazzo Venezia in Rome.

Italy had so far remained neutral in the conflict but believing German victory imminent he declared that he only needed a thousand Italian dead to be able to sit at the conference table and reap the spoils of war. He told them: "People of Italy! To arms, show your spirit, your courage, your valour!"

With much of central and western Europe already under German occupation Mussolini now eyed conquests of his own, namely the expansion of Italy’s Mediterranean and North African Empire.

Following the capitulation of France and with Britain apparently destined to do the same Mussolini hastily reinforced the Italian garrisons in Libya and Abyssinia in preparation for a two-pronged assault on British controlled Egypt.

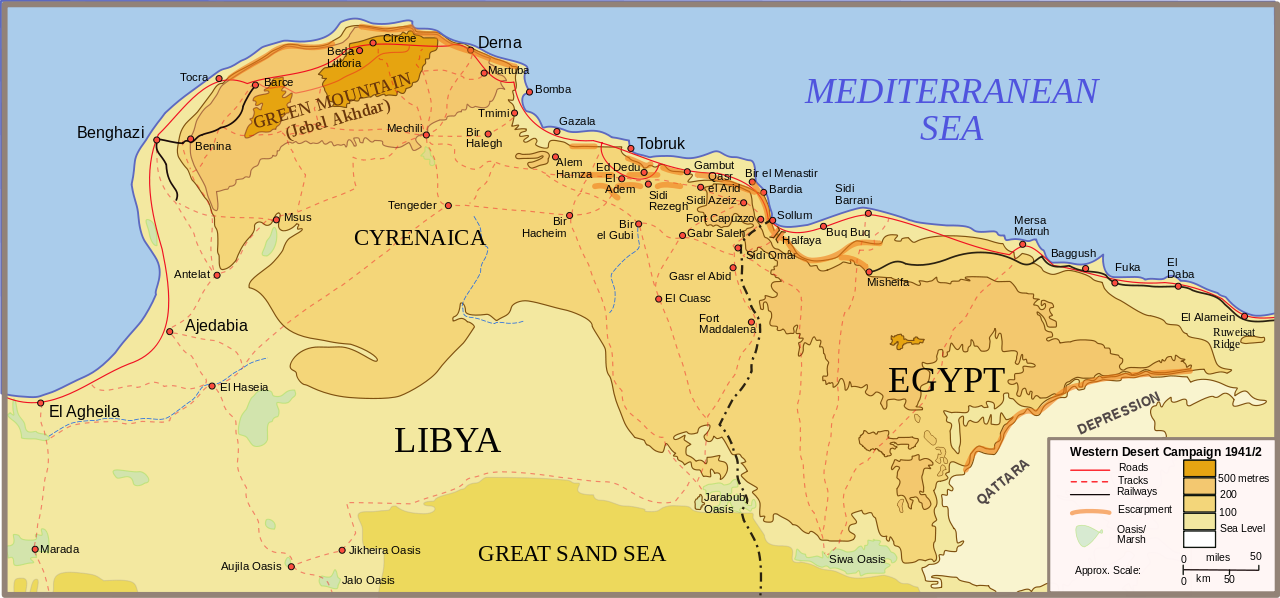

The Italian Army in Abyssinia would soon become bogged down in an East African campaign that would result in its defeat and eventual surrender in April 1941, but regardless of events elsewhere the invasion of Egypt would go ahead. On 9 September, 250,000 Italian troops in three great columns set off across Cyrenaica for Egypt making rapid progress as the 36,000 men of the British Western Desert Force confronting them had little choice but to beat a hasty retreat.

Despite his huge numerical superiority the Italian Commander General Rodolfo Graziani, an ardent fascist who had earned the name ‘Butcher’ for his brutal suppression of rebellion in Libya doubted that his ill-equipped, half-trained, poorly motivated army could succeed and had already delayed the advance a number of weeks Yet unopposed in just four days they reached Sidi Barrani, 60 miles inside Egypt but still some 400 miles short of Cairo.

Here with his line of communications stretched and vulnerable to attack from the air he called a halt and ordered the building of numerous fortified camps where he waited allowing the British time to regroup and re-think their strategy. In November 1940, under the command of General Richard O’Connor they counter-attacked.

The Italian camps had been built too far apart to offer each other any support and in the desert terrain it was easy for the British armour to go around and attack them from the rear. This they did with startling success as what had been intended as little more than a reconnaissance in force with limited objectives turned into a full-scale offensive as out- manoeuvred and overrun the fortifications fell one-by-one with great rapidity and often little resistance in what resembled mopping up operations rather than pitched battles.

By February 1941, with the Italians in full retreat the British had re- taken Sidi Barrani, Tobruk, Beda Fomme, Benghazi, and were advancing on Tripoli.

The Italian Tenth Army had been smashed in just three months of fighting with 5,700 troops killed and 133,298 taken prisoner along with 420 tanks and 845 guns.

At the cost of fewer than 2,000 casualties it seemed as if O’Connor was on the verge of chasing the Italians from North Africa altogether but Prime Minister Winston Churchill believing the war in the desert as good was won called off the offensive withdrawing troops and mechanised units for his planned campaign in Greece – a great triumph had become an opportunity lost.

Mussolini’s dream of Mare Nostrum, a great Italian Empire dominating the Mediterranean and a military victory to compare with any of his ally Adolf Hitler’s had been shattered and as he hastily reinforced what remained of the Tenth Army he pleaded with the Fuhrer to come to his support. Hitler, unwilling to see his ally humiliated did indeed ride to his rescue and who was better equipped to fight a desert campaign than the master of mobile warfare, his favourite General, Erwin Rommel.

RRommel arrived in Tripoli on 12 February 1941, to take charge of the recently formed Panzer Armee Afrika, or Afrika Korps. He had not been the choice of the German High Command but Hitler’s alone, yet even with the Fuhrer’s endorsement it was intended that his freedom of action should be restricted and so he was made subordinate to Italian command, a decision which also went some way to restoring II Duce’s wounded pride. But this would prove less of an impediment than first thought in large part because he simply chose to ignore it.

Rommel’s Afrika Korps was by no means a large army, just two Divisions, some 45,000 men and 120 tanks, but then it was only intended that they should shore up the Italian Tenth Army and remain on the defensive.

There was little prospect of Rommel doing either and impatient as ever he was already planning for the campaign ahead ordering his tanks even as they were being unloaded onto the dockside to drive repeatedly around the block to deceive the prying eyes of British spies whilst instructing his Chief Engineer to build dozens of fake canvass tanks to fool aerial reconnaissance.

His Afrika Korps were already taking up position in the front-line even before their equipment had been fully disembarked and as ordered they made as much noise and kicked up as much dust as possible – British Intelligence reported large German formations heading east.

On 24 March, Rommel advanced into the Cyrenaican Desert totally wrong-footing the British who had not been expecting a major offensive for many months and stripped of three of their best Divisions for operations in Greece they were ill-equipped and even less prepared to meet one.

El-Agheila, Bardia, and Benghazi all quickly fell as mesmerised by the speed of the advance the British response was little less than shambolic. Desperately scrambling to avoid being surrounded and cut-off they abandoned not only vast quantities of supplies but any number of Senior Officers who were taken prisoner among them the now famous General O’Connor captured on 6 April by a Reconnaissance Group, or as German propaganda were to later claim, a Canteen Unit.

By the 11 April, when the British at last stabilised their line just beyond the Egyptian border only the port of Tobruk still held out.

Although deeply frustrated by his failure to capture Tobruk, which nonetheless remained under siege, Rommel had achieved a victory beyond even his own expectations. In a little over three weeks, he had recaptured all the ground previously lost by the Italian Tenth Army. It was a stunning success that left the British bewildered.

But Tobruk, now more than a hundred miles behind German lines and able to be re-supplied by sea posed a threat to Axis lines of communication that could not be ignored, neither could the so-called Desert Rats be dislodged, so Rommel had to commit much of his army to its continued investment which left him vulnerable elsewhere. Or, at least, it should have done.

The British Commander-in-Chief Middle East General Archibald Wavell certainly thought so and on 15 May launched Operation Brevity, a limited offensive designed to capture the strategically important Halfiya, soon to be renamed Hellfire, Pass. After some initial success German counterattacks soon recaptured all the ground lost and the offensive was cancelled after just one day.

Under pressure from the Government in London, Wavell was to try again.

Operation Battleaxe which began on 15 June was much more ambitious in its scope than its predecessor intended as it was to eject all Axis Forces from Eastern Cyrenaica thereby clearing a path to Tobruk and the relief of its garrison. Believing they had numerical superiority, Churchill, if not Wavell, was confident of success but forewarned of the offensive Rommel had deployed his armour in advance.

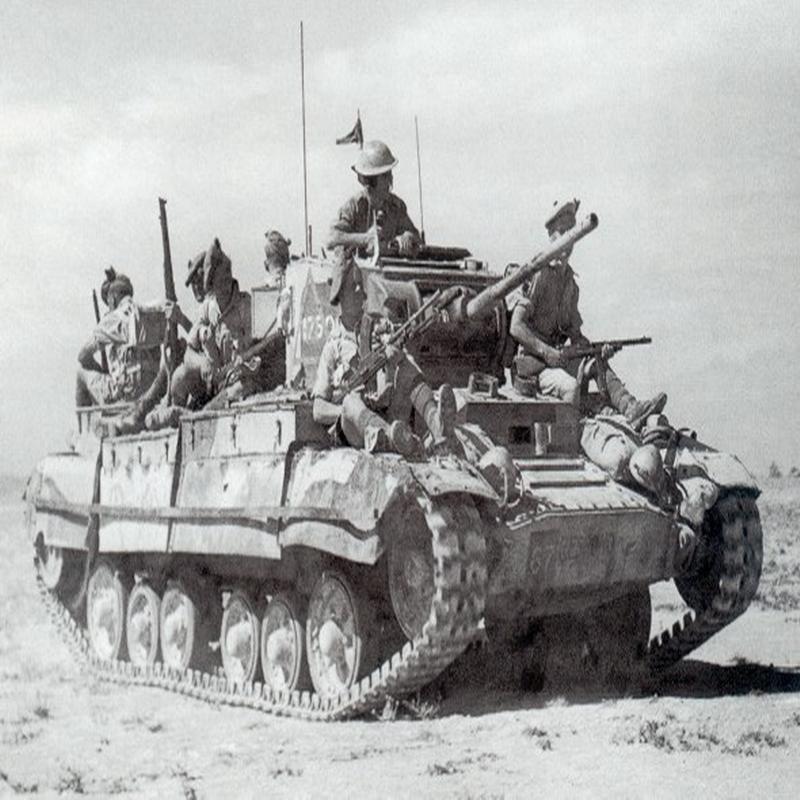

Not for the last time a British campaign in the Western Desert was to be blighted by poor communication and a lack of co-ordination and this time it would be early failures that would undermine later success.

In response to the offensive Rommel adopted what would soon become a familiar tactic, as the British advanced his Panzer Mark IVs would engage out of range their lightly armed Matilda and Crusader tanks which would race to close the distance. As they did so the Panzers retreated exposing the British armour to the full weight of his 88mm guns and heavy artillery whilst armoured cars and motorised Divisions moved to outflank the British position. It was a tactic that Rommel used again and again and to great effect.

British and Allied troops often under fire it seemed from all directions and hampered by poor quality radios that were often barely audible if they worked at all, were often thrown into a state of confusion not knowing whether to advance, retreat or simply remain where they were.

The fear of being outflanked and surrounded was a constant and often led to unnecessary evacuation, premature flight, and the wasteful abandonment of equipment.

After three days of fighting Operation Battleaxe was called off having achieved none of its objectives. The British had lost over a thousand men and 96 tanks more than half of those deployed all of which were left abandoned on the battlefield. The Germans, who lost only 12 tanks, retrieved those of the British that could be repaired. It was an example of the sloppiness that came to dominate British operations during the Desert War.

Churchill was bitterly disappointed by the failure of Operation Battleaxe, not only was it yet another morale sapping defeat but many of the tanks lost had been despatched from a Britain still under threat of invasion and which they could ill-afford to lose.

As a result, General Wavell was fired and replaced with General Sir Claude Auchinleck.

The soon to be Desert Fox had twice been tested and had twice prevailed – but at least Tobruk still held out.

Following the fiasco of Operation Battleaxe there was a lull in the fighting as both sides reorganised for the coming campaign. Rommel flushed with success was eager to proceed with the capture of Tobruk, but it was the British for whom re-supply was easier who struck first.

In August, Auchinleck appointed Lieutenant-General Alan Cunningham to command the recently re-designated Eighth Army and prepare for a major offensive. Operation Crusader which began on 18 November 1941 was intended to engage and destroy the Axis armour and relieve Tobruk. It was felt that Rommel would commit his forces recklessly to maintain his stranglehold on Tobruk and so as the British engaged Axis forces elsewhere on the front 7th Armoured Division would clear a path and advance on the port.

Rommel took the bait and fought with his usual verve and determination but an operation that was intended to take full advantage of the element of surprise was once again bungled and soon became a confused and protracted struggle. As the 7th Armoured Division closed in on Tobruk, Rommel attacked in force near Sidi Rezegh in what would be four days of the fiercest fighting seen anywhere during the Desert Campaign.

Making expert use of their 88mm guns the Afrika Korps took a terrible toll of the 22nd Armoured Brigade reducing it to the point where it ceased to be an effective fighting force yet despite being denuded of their armoured support the New Zealand Division and the 5th South African Brigade held their ground with the latter having to be quite literally overrun before its stubborn resistance was finally broken.

Yet again a British offensive appeared to have stalled and Cunningham displaying a loss of nerve repeatedly requested to be allowed to withdraw back to Egypt. Auchinleck, despairing at his lack of resolve replaced him with Major-General Neil Ritchie.

Flushed with his success at Sidi Razegh, and perhaps again not seeing the bigger picture, Rommel now seized the opportunity to attack the British defences before Egypt in what became known as the ‘Dash for the Wire.’

Ritchie allowed the Axis forces to pass subjecting them to artillery bombardment and constant attack by the Desert Air Force whilst severing their lines of communication and supply. Frustrated by the delaying tactics, short of ammunition, and forced to abandon precious tanks for a lack of fuel Rommel had little choice but to order a general withdrawal.

The Desert Fox had over-reached himself and his reckless pursuit of outright victory resulted in the relief of Tobruk on 27 November and a retreat all the way back to his starting point at El-Agheila the previous March. Yet despite his losses it had been an orderly withdrawal and his army remained intact.

Operation Crusader had succeeded where it had appeared destined to fail so it was a victory of sorts, and the relief of Tobruk was joyously received but the Desert Campaign remained far from over. On 21 January 1942, Rommel briefly counter-attacked recapturing Benghazi but there he halted. Both Axis and Allied forces were exhausted and depleted of supplies but they both intended to resume the offensive as soon as possible – it was Rommel who struck first.

On 26 May, he assaulted the British positions in and around the town of Gazala in a diversionary attack whilst he mobilised the bulk of his army to turn the enemy’s left flank. The British response was confused and hesitant as they counter-attacked in some places while withdrawing in others allowing the ever elusive Rommel the opportunity to isolate British formations and destroy them piecemeal.

With no armoured reserve there were times when a British counterattack appeared about to derail the German offensive but Rommel would not be deflected from his course of action and a lack of coordination and strategic purpose would see them come to nothing.

On 28 May, Rommel had to temporarily halt the offensive due to a shortage of oil and had to await supplies, but the British proved incapable of seizing back the initiative. Two days later he resumed the offensive and was soon besieging the fortress of Bir Hacheim on the far left of the Allied line whilst sending forces to probe north in the direction of Tobruk. The British fearing encirclement began to hastily withdraw.

Bir Hacheim was defended by Free French Forces many of them Foreign Legion and Colonial Troops from Equatorial Africa. Out-numbered almost ten-to-one the French were expected to surrender but in fact held out for over a week not finally abandoning their positions until 10 June.

The stout defence at Bir Hacheim had provided invaluable breathing space to Auchinleck who had replaced Ritchie and taken personal command. He now retreated 100 miles to the Railway Halt at El Alamein, a withdrawal he was able to make in some semblance of good order.

On 21 June, Tobruk which had previously withstood a nine-month siege and had become a symbol of British resistance during the dark days of the Blitz and military failure elsewhere fell in just 24 hours. Although it had remained well-garrisoned its defences had been neglected and fallen into disrepair and there had also been some confusion as to whether the port should continue to be defended at all, but a humiliating capitulation had certainly not been the intention. Despite some units managing to escape into the desert during the night some 36,000 prisoners were taken among them a third of South Africa’s entire army along with stores aplenty.

Despondency overwhelmed the Allied camp and Churchill who was in Washington for a meeting with President Roosevelt received the news with disbelief and plunged into despair had to be comforted by the President as he bemoaned the incompetence of his Commanders and the fighting spirit of his troops – these were not the men of 1914, he remarked.

The capture of Tobruk was the crowning moment of Rommel’s military career and the machinery of Joseph Goebbel’s Propaganda Ministry immediately whirred into action.

Stating that the capture of Tobruk was his personal gift to the Fuhrer the Desert Fox was flown to Germany where attending a ceremony in Berlin he was promoted and awarded his Field Marshal’s baton by Hitler in person as the cameras rolled and the images flashed around the world. The legend of the Desert Fox was born but it wasn’t just his capture of Tobruk and success in time-and-again denying the odds to thwart and defeat a superior enemy but the manner in which he conducted the campaign so removed as it was from the brutality of the Eastern Front.

Atrocities if there were any were few and prisoners generally well-treated. Indeed, Rommel insisted they should receive the same rations as he and often visited their places of internment to check on conditions. He also refused to implement Hitler’s notorious Commando Order which demanded that they be shot if captured and similarly he would not execute captured Jewish soldiers or hand them over to the SS.

He would adhere to his dictum of ‘war without hate’ and to many who fought in the Desert Campaign it was the last honourable war, if indeed there can be such a thing.

It was not just his speed of thought and deed such as adapting the 88mm anti-aircraft gun for use against enemy armour making it the most feared weapon of the Desert War and deploying his mobile forces in such a way as to constantly confuse and confound an always superior opponent but his common decency that made him a hero to both sides something which German propaganda was eager to exploit and did so unremittingly and to great success – he was the acceptable face of the Third Reich.

His victories were also a welcome distraction from the increasingly intensive bombing of German cities, the grim reality of war on the Eastern Front and the growing awareness that this was to be a prolonged struggle seemingly without end.

Churchill suspected that an admiration for Rommel had infected his own army which no longer had the sufficient will to resist him. It was not a groundless fear.

By the end of June, the Axis positions were just 66 miles from Alexandria and Rommel, so often criticised for spending too much time at the front and treating every battle as if it was being fought in his own backyard now had a strategic vision of his own. If he could breakthrough at El Alamein then surely the Suez Canal would be taken, Egypt would fall, the oil fields of the Middle East would be laid bare and he could advance to link up with German forces in the Caucasus.

But it was not a vision shared by the Fuhrer who still saw the Desert Campaign as primarily a holding operation and he would not divert forces from the Eastern Front to the Afrika Korps despite his often-vague promises to do so.

El Alamein stood at the apex of a bottleneck with the sea to the north and the Quattara Depression, a vast area of sand dunes and salt marshes impassable to motorised transport, to the south. It meant that the British defences could not be outflanked and that for Rommel to succeed he would have to force a way through.

Nonetheless, Mussolini believing victory imminent flew to Tripoli, his best uniform packed determined to share the moment and no doubt claim the credit. In the meantime, General Auchinleck issued a directive to his Senior Commanders stating that Rommel was neither a superman nor invincible, should not be thought of as such, and that this should be relayed to the men as soon as possible.

Rommel’s victory at Gazala had sent shockwaves through British Headquarters in Cairo where in an atmosphere of panic and fearing the Desert Fox’s imminent arrival confidential documents were burned and preparations made for a hasty withdrawal.

The narrowness of the front Auchinleck believed provided hi m with the opportunity to dictate the course of the battle by creating defensive boxes that would funnel the Axis armour into confined spaces where it could be destroyed. He declared that he would halt Rommel at Alamein and even turn the tide of the campaign, but it was not a view widely shared.

Rommel began his offensive on 1 July.

Yet again he was outnumbered almost 2 to 1 in both men and armour yet sensing the British were at breaking point he remained confident of victory, but the terrain was not in his favour. Under clear blue skies and in open desert his columns were particularly vulnerable to attack from the Desert Air Force which despite frantic efforts to kick up dust and make smoke bombed and strafed incessantly taking a terrible toll.

Despite repeated attempts to cut the coast road, to isolate and destroy British positions and tempt them by a series of feints to leave their defences he could make little headway and having fought his army to the point of exhaustion was forced to withdraw. Here was yet another opportunity for a British Commander to seize the initiative and claim a decisive victory but when the counterattack came it once more foundered on poor coordination and muddled thinking. Even so, Egypt had been saved the Rommel myth dented.

Auchinleck’s victory at what would become known as the First Battle of El Alamein did not sufficiently restore his reputation enough to secure his job and in August he was replaced as Commander-in-Chief by General Sir Harold Alexander whilst the recently promoted Lieutenant-General William Gott was appointed to command Eighth Army. When Gott was killed in a plane crash a few days later General Bernard Law Montgomery was hastily summoned to replace him.

Montgomery or Monty as he was soon to become known had been a Battalion Commander on the Western Front in the Great War and had played a prominent role during the retreat to Dunkirk in May 1940.

A prickly character who was often in dispute with his superiors he was nonetheless the consummate professional who may have lacked his German opponents daring but none of his self-confidence and firmly believed that given sufficient manpower and resources he could defeat Rommel, and he wasn’t shy in saying so: “Give me a fortnight and I can resist the German attack. Give me three weeks and I can defeat the Bosch. Give me a month and I will chase him out of Africa.” Indeed, such was his self-belief that even the often-despondent Churchill was impressed.

He did not fear the Desert Fox he said, but he did respect him enough to have his photograph hanging in his trailer. But he would not be rushed, and nothing would be left to chance.

First he would restore the morale of the Eighth Army and retrain its soldiers for the battle to come; and with his distinctive high-pitched, cut-glass accent and trademark headwear he was to prove no less inspirational to his troops than Rommel was to his Afrika Korps.

Rommel, eager to test this new British Commander determined to turn the Allied left flank and then push onto the Suez Canal but informed of his intentions from Ultra decrypts Montgomery withdrew five miles and took up position on the more defensible Alam Halfa Ridge. Here troops dug-in, mines were laid and he had his tanks buried up to their turrets in sand to be used as artillery only. This would be a defensive battle and Montgomery had ordered that there would be no withdrawal, and he remained no less determined that there would be no advance.

Rommel attacked on 30 August and maintained the offensive for a week but Montgomery would not be drawn and unable to dislodge the British and force a breakthrough he had little option but to withdraw to the Cauldron, a defensive position behind a dense minefield.

Despite his failure at Alam Halfa, Rommel remained confident that he had the measure of his opponent who had shown himself no less timid and cautious than his predecessors but for the first time in private he expressed doubts that he could ever achieve outright victory.

Montgomery was immediately put under pressure from both Churchill and Alexander to exploit his victory but refused to be diverted from preparations for his own planned offensive.

Leading a polyglot force of British, Australian, New Zealand, South African, Free French, Polish and Greek troops he well understood the limitations of a Citizen Army, those who had not been raised in an atmosphere of militarism and racial superiority and a fanatical devotion to one man. Nonetheless he believed a well-trained, adequately resourced, properly led army made aware of the cause they were fighting for could still prevail.

Prior to the battle Monty addressed the troops: “The battle which is now about to begin will be one of the decisive battles of history, it will be the turning point of the war. The eyes of the whole world will be upon us anxiously watching which way the battle will swing? We can give them their answer at once – it will swing our way.”

Monty had prepared well and built up his forces sufficiently to obtain a clear supremacy in manpower, armour, and in the air. He had 195,000 men under his command, 1,029 tanks, and a Desert Air Force recently reinforced by an additional 4 Squadrons of American Mitchell Bombers.

Rommel could call upon 105,000 men (55,000 of whom were Italian) and 547 tanks (fewer than half of which were Panzers) along with Luftwaffe support. Outnumbered though they may have been they were well dug-in behind reams of barbed wire and more than 500,000 land mines.

At 21.40 on 23 October 1942, 882 guns opened up on the Axis forward positions with a roar that shook the ground and lit up the dark desert sky.

Under the cover of this thunderous bombardment Operation Lightfoot began as thousands of Sappers moved forward in the gloom to clear a path through the minefields for the armour to follow.

As the greatest land battle of the Western Desert Campaign began Rommel was far away at home recuperating from exhaustion and a bout of ill-health.

On 24 October, whilst on an inspection of the front-line General Georg Stumme, in temporary charge of the Afrika Korps dropped dead of an apparent heart attack When Rommel returned the following day he was furious with Stumme’s replacement General von Thoma for not having already ordered a counter-attack.

Quickly assessing the situation Rommel found that his Italian Divisions had been particularly badly mauled, and his armour severely reduced by aerial bombardment. He could not therefore order a general offensive across the line, but he would attack where he could.

A lack of fuel would ensure that his aggressive response would meet with only limited success but the British offensive would stall nonetheless. In London Churchill despaired remarking: “Do I even possess a General who can win a battle?” Montgomery certainly believed so and was determined that the fighting should not descend into a stalemate even so maintaining the momentum was proving difficult. Even so, the odds remained firmly in his favour.

When on 28 October, two Panzer Divisions with infantry support attacked the centre and left of the Allied line they clashed with British armour resuming the offensive and a struggle ensued, that saw the Germans repulsed with heavy losses. It was fighting that Rommel could ill-afford – he wrote to his wife: “For the first time in my life I did not know what to do.”

With defeat looming Rommel contacted German Headquarters requesting permission to withdraw. The response he received left him bewildered – he was to remain where he was and fight to the last man. In disbelief, he asked for the order to be repeated. It was, and it had come direct from the Fuhrer.

The order made no military sense whatsoever yet for two days he dithered at great cost to his army as the fighting intensified. Finally on 4 November with just 35 tanks remaining and his faith in the Fuhrer severely shaken he ordered a general retreat. As the Afrika Korps withdrew it commandeered the mechanised transport of its Italian allies literally kicking from the vehicles those who tried to hitch a lift.

Although their performance had improved under his command and some units had fought very well indeed their earlier humiliations were not easily forgotten either by themselves or by the Commander of the Afrika Korps who remained largely scornful of the Italian element of his army and their overall contribution.

Armed with inferior equipment, poorly led and often denied fuel and supplies it was these troops who had borne the brunt of the attack at El Alamein who would be the ones now sacrificed – of the 35,000 Axis prisoners taken almost all were Italian. Indeed, the disciplined withdrawal of the Afrika Korps contrasted sharply with the shambles of their ally and many Italian soldiers were to complain bitterly of the lack of leadership from their own Officers many of whom simply abandoned them as their retreat descended into chaos.

Assisted by poor weather which grounded much of the Allied Air Force, a series of well-directed delaying actions, and Montgomery’s own caution the Afrika Korps was able to extricate itself intact avoiding the rout that had seemed inevitable, but the retreat was to be a long and painful one.

IInformed by Alexander that the Afrika Korps was beaten and Rommel was in full-flight Churchill ordered that Church bells be rung throughout Britain. After three years of desperate struggle for the first and only time in the war a British Army had comprehensively defeated a German one on the field of battle. On 10 November, Churchill addressed the House of Commons: “General Montgomery has gained a glorious and decisive victory . . . Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

Two days earlier, as part of the American led Operation Torch, Allied troops landed in Vichy French held Morocco and Algeria and already pursued by the British in the East Rommel was now threatened by the Americans advancing from the West.

The end appeared to be in sight but the Allied advance remained sluggish and, despite a retreat of more than 2,000 miles and the hasty abandonment of Tripoli, Rommel was still able to win the race to Tunisia and thwart the Allied attempt to sever his line of retreat – and he wasn’t finished yet.

On 19 February 1943, he turned on his pursuers halting the United States II Corps at the Battle of Sidi-Zou-Bid before luring them into the Kassarine Pass where adopting the tactics that had worked so effectively against the British earlier in the campaign he drew the American armour onto his 88mm guns and destroyed it. Only a hasty and undignified retreat prevented a rout. It was a harsh lesson in desert warfare for the tactically inept, raw and not yet battle-hardened Americans but one they learned quickly.

But without the resources to fully exploit his victory it also served as a lesson for Rommel too, that much like Napoleon Bonaparte more than a hundred years before no amount of battlefield genius can overcome overwhelming odds in a sustained campaign.

On 6 March, he turned his attention on the British but there were few tricks left in his locker that Montgomery wasn’t aware of and with the British remaining on the defensive the two day Battle of Medenine was yet another bitter struggle fought to no good purpose which the increasingly beleaguered Desert Fox could no longer afford.

In truth, Rommel knew that the Desert War was lost and repeatedly pleaded with Hitler to withdraw the Afrika Korps to mainland Italy before it was too late. Ironically, it was only now on the cusp of defeat that Hitler began to take the conflict in North Africa seriously and begin to send the reinforcements that earlier in the campaign might have proved decisive for he now saw an opportunity to turn Tunisia into a fortress that would bog down the Americans in a long and bloody siege that would both sap their enthusiasm for the fight and prevent them from intervening elsewhere.

But Rommel would have no further role to play in the Fuhrer’s latest strategic master-plan and was ordered home on 9 March to be replaced by his subordinate General Hans-Jurgen von Arnim. The Desert Fox would be spared the humiliation of defeat.

The fighting in Tunisia was to continue for a further two months but it unable to adequately supply such a large force across a Mediterranean swarming with Allied plane, surface vessels, and submarines it had become in effect little more than a giant self-imposed internment camp.

The formal surrender of all Axis Forces in North Africa was accepted on 12 May, 1943. In total, some 275,000 prisoners were taken of which 130,000 were German along with all their tanks, artillery, and war materiel. It was a defeat larger in scale than that suffered by the Sixth Army at Stalingrad and Hitler’s decision to reinforce rather than withdraw his army in North Africa was one of the great strategic blunders of the war.

But the fact that Rommel was not present at the denouement enhanced his reputation further viewed as it was through the prism of his successors defeat.

The Poison Chalice

Field-Marshal Rommel’s reputation for daring was undeniable but his ability as a Commander had been brought into question more than once. He had after all, never commanded large formations and had not served in the cauldron of the Eastern Front. He had also in the end failed to deliver victory in North Africa. Some suggested he’d had it easy and had been promoted beyond his capability. Yet he was to most Germans the ‘Desert Fox’ and their greatest living General and he returned to the country a national hero.

The fluid nature of the Desert War had provided opportunities for glory absent on other fronts and his exploits were well received. As also was his oft-repeated maxim ‘war without hate’ and the apparent humanity with which he waged it. It was something that Joseph Goebbels and his Ministry of Propaganda and Enlightenment continued to exploit to the maximum.

As such the need to protect his reputation was paramount so much so that when with defeat looming he flew to Hitler’s Headquarters at the Wolf’s Lair to plead with him to withdraw the Afrika Korps to mainland Italy it had been decided to withdraw him instead.

The Desert Fox he might be but he still wasn’t entirely trusted by the German High Command many of whom thought him rash, unpredictable and promoted ahead of those better qualified. He was also thought unsound by some within the Nazi hierarchy who aware that he had never been a member of the party also resented his personal relationship with the Fuhrer.

Upon his return he was briefly considered for Commander-in-Chief of the Army but this was dismissed on the grounds he was a maverick and he was soon to find himself spending more time with his family than he might otherwise have expected. He was then a hero without a role and there appeared little urgency on the part of his superiors to find him one.

Even so, the newsreels were rarely absent – the Desert Fox at home, the Desert Fox with the Fuhrer, the Desert Fox with Magda Goebbels and her adorable children.

On 23 July 1943, he was appointed to command the army in Greece but was replaced just two days later, and in August was appointed Commander-in Chief in Italy but Hitler not liking his proposals for its defence soon replaced him with the Luftwaffe General Albert Kesselring, a long term critic of Rommel’s who also had the Fuhrer’s ear.

It was a deeply frustrating time and he complained bitterly to friends that he was being side-lined, that he was not being kept abreast of the military situation and only learned of events from the newspapers.

In October 1943, he was visited at his home in Herlingen by his old friend Karl Strolin, the Mayor of Stuttgart, who informed him of the conditions in the Concentration Camps and the mass-killings of Jews. Like many others he refused to believe that such rumours could be true but with time on his hands it left him with much to ponder – were such unspeakable atrocities truly being committed in the name of the German Army? Could the Fuhrer possibly be aware of such things, perhaps even condone them?

With the war turning against Germany in the East and Allied intervention in the West imminent Rommel’s absence from command was becoming increasingly difficult to sustain. This changed early in 1944, when he was given responsibility for overseeing the coastal fortifications of Western France, the place where any Allied Invasion Armada would be expected to land.

Portrayed as the Third Reich’s first line of defence and known as the Atlantic Wall, he soon discoverer it was no such thing.

Shocked by the neglect he found he threw himself into his new role with all the vigour and enthusiasm to be expected of Germany’s greatest General, though it was remarked by those who knew him well that he was a changed man. Not that the public would have guessed from the newsreels that relayed his frequent tours of inspection as the Desert Fox brimming with confidence and carrying his trademark Field Marshals baton became a familiar sight on German cinema screens.

Propaganda aside there was in truth much work to be done as he mined the beaches, ordered the construction of artillery emplacements, anti-tank traps, hundreds of concrete pill-boxes and built concealed underwater obstacles.

But the Allies had gone to great lengths to mislead the German High Command into the location of the planned invasion convincing them that it would be the Pas-de-Calais, the shortest route across the Channel from England which was where much of the reconstruction work was concentrated – they would in fact come ashore further south, at Normandy.

Rommel was also at loggerheads with his immediate superior Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt over how best any defence should be conducted. He believed that the invasion must be resisted at the point of contact on the beaches before the Allies could gain a foothold, and that the Panzer Divisions should be brought forward and prepared for an immediate counter-attack. Von Rundstedt disagreed ordering the German Armour held in reserve for a defence in-depth.

At the same time as Rommel contemplated how best to resist the expected invasion when it came others were already seeking to end the war with the Western Powers by other means.

That there were those within the Officer Corps unhappy with Hitler’s conduct of the war was no secret, that some were seeking to remove him from power certainly was. But who could be trusted and who could not was difficult and dangerous to ascertain, who might refuse to participate in the plot but also not betray them even more so.

Rommel’s personal relationship with Hitler made his support uncertain, but then he was also known to have had his differences with the Fuhrer. Slowly he would be drawn into the plot but he would not countenance Hitler’ murder. He must be brought before a Court of Law and stand trial for his crimes just like any other man. It was a clear indication of his political naivety.

He was to be disavowed of any such notion when he was subjected to one of the Fuhrer’s increasingly familiar paranoid, table-thumping tirades that saw him physically removed from his presence. It wasn’t the first time that following a disagreement he had been ordered to leave but on previous occasions he had been invited back – but not this time.

Even now, Rommel was inclined to excuse the Fuhrer’s behaviour on the grounds that he was a man under great stress but in private with his confidence in Hitler already shaken by his sacrifice of the Afrika Korps and the Sixth Army at Stalingrad he began to believe he was at the end of his tether, that he might even be losing his mind.

In private meetings he sounded out others regarding Hitler’s removal including Field-Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt who despite his personal disdain for the ‘Bohemian Corporal’ remained uncommitted and refused to hear the details of any plot. But then all German Officers had sworn an oath under God to serve not the State or the Constitution but the person of the Fuhrer Adolf Hitler. It was an oath not easily broken moreover it was a treasonable to do so and punishable by death.

The ‘July Plotters’, particularly those of the Kreisau Circle were mostly serving Officers of the old Prussian Aristocracy and retired or side-lined Senior Officers of the Wehrmacht and as an outsider Rommel was not entirely trusted but he was the one man who all felt the people might willingly follow should Hitler be assassinated. Even so, any role for him in a post-Nazi regime remained vague. In the meantime, he had a war to fight.

On 6 June 1944, the Allies came ashore at Normandy. In the days preceding the weather had been so inclement that the Germans had ruled out any immediate prospect of invasion and Rommel had returned home to be with his wife on her birthday. He returned at once only to find that the Atlantic Wall had proven unequal to the task and except for at Omaha Beach where the Americans had almost met with failure the Allies had faced mostly token resistance and by nightfall with the beachheads secured 155,000 men with armoured support were already moving inland. They would be quickly reinforced.

Rommel again argued for the implementation of his plan to strike the Allies hard whilst they remained vulnerable. In a final heated exchange with Hitler at Margival in France on 17 June, the Fuhrer relented a little and released three Panzer Divisions to his command but without the total freedom to use them as he wished. It was in any case, too late.

The war in the West soon bogged down into a close-quarter infantry struggle that would not have been unfamiliar to veterans of the Great War just as Field Marshal von Rundstedt had predicted it would.

This was not the war of manoeuvre in which the Desert Fox excelled and denied the opportunity to use his Panzer’s as he wished due both to Allied air superiority and Hitler’s constant interference, he became increasingly despondent. In such a struggle overwhelming Allied manpower and resources must inevitably prevail. He thought the war lost and more than once wrote to the Fuhrer declaring the army close to disintegration and pleading with him to bring the war in the West to an end – he received no reply.

On the evening of 17 July, not far from the ironically named town of St Foy de Montgomerie, Rommel’s staff car was strafed from the air by a marauding Spitfire and forced from the road; thrown from the car he sustained a fractured skull and shrapnel wounds to his body and face. In truth, he was lucky to be alive and after spending some time in hospital he was sent home to recuperate.

Three days later on a visit to Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair Headquarters in East Prussia, Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg placed his briefcase containing a bomb beneath the desk where Hitler was standing. In such a windowless and confined space, the impact of the explosion should have been devastating, that it wasn’t sealed the conspirator’s fate.

Although some were killed and others severely injured by a quirk of fate Hitler emerged badly shaken, his clothes torn but otherwise unscathed. Operation Valkyrie, the plot to assassinate the Fuhrer had failed and over the following days those responsible would be hunted down, arrested and killed.

Rommel was not at first suspected of being involved in the plot but would soon be implicated by others among them General Carl-Heinrich von Stulpnagel who in custody repeatedly mumbled his name whilst delirious following a failed suicide attempt and Carl Goerdeler, the man nominated to replace Hitler as Chancellor who had drawn up a list of possible Presidents of the new regime one of whom was Erwin Rommel.

It was Martin Bormann, the so-called ‘Brown Eminence’ who as Hitler’s personal secretary jealously guarded access to the Fuhrer who first brought Rommel’s involvement to his attention.

On scant evidence, Hitler was at first disinclined to believe him but with little support for Rommel from other quarters in particular Joseph Goebbels the man who had done more than any other to create the legend of the Desert Fox but had now abandoned him in fear of also becoming a victim of Bormann’s malicious intent, he was eventually persuaded. Even so, he refused to believe that Rommel had been actively involved in the attempt to assassinate him but was willing to accept that he had been aware of the plot and had done nothing to prevent it, and as such he was as guilty as those who had carried it out.

Recuperating at home with his family Rommel was unaware that he was already being tried in absentia by the Court of Military Honour (upon which sat both Gerd von Rundstedt and Erich von Manstein) established to determine the guilt of serving Officers in the plot and whether they should face justice in the Peoples Court.

The prospect of the legendary Desert Fox being brought before the Peoples Court and its vituperative Chief Justice Roland Freisler was not only unpalatable to the Regime and the German High Command but the damage it might do to public morale was difficult to gauge. It needed to be avoided if possible.

On 14 October, as his house in Herlingen was being surrounded by a unit of SS a car drew up occupied by General Wilhelm Burgdorf and General Ernst Maisel along with a wreath with a message of condolence attached signed, Adolf Hitler.

Burgdorf and Meisel, both of whom had been harsh critics of Rommel in the past, curtly but respectfully informed him that his complicity in the July Plot had already been proved and that he would face trial in the Peoples Court. The Fuhrer however, cognisant of his devoted service to the Third Reich was willing to allow the Field Marshal the option available to an Officer and a gentleman, that is, to take his own life.

Rommel’s first instinct, as one might expect from a man whose career had been made from taking the fight to the enemy was to defend himself against his accusers. But it wasn’t that simple. Were he convicted, as was certain then his family would be considered no less guilty than he and would suffer accordingly. Their property would be confiscated, and they would face likely detention in a Concentration Camp. Also, his staff guilty by association would be executed alongside him.

If he were to commit suicide and pre-empt the need for a trial then he would be accorded a State Funeral with full military honours. His rank, status, reputation, and pension would be assured and the safety of his family guaranteed on the word of the Fuhrer. Regardless of the desire to clear his name the choice were obvious.

His son Manfred, then serving in an anti-aircraft battery (his father had earlier refused his request to enrol in the Waffen SS) described events:

“At about twelve o’clock a dark-green car with a Berlin number plate stopped in front of our garden gate.

The only men in the house apart from my father, were his aide Captain Aldinger , a badly wounded war veteran, and myself.

Two generals, Burgdorf, a powerful florid man, and Maisel, small and slender, alighted from the car and entered the house. They were respectful and courteous and asked my father’s permission to speak to him alone. Aldinger and I left the room.

“So they are not going to arrest him,” I thought with relief, as I went upstairs to find myself a book.

A few minutes later I heard my father come upstairs and go into my mother’s room. Anxious to know what was afoot, I got up and followed him. He was standing in the middle of the room, his face pale. “Come outside with me,” he said in a tight voice. We went into my room.

“I have just had to tell your mother that I shall be dead in a quarter of an hour. To die by the hand of one’s own people is hard but the house is surrounded and Hitler is charging me with high treason.

In view of my services in Africa I am to have the chance of dying by poison. The two generals have brought it with them. It’s fatal in three seconds. If I accept, none of the usual steps will be taken against my family. They will also leave my staff alone.”

“Do you believe it?” I interrupted. “Yes,” he replied. “I believe it. It is very much in their interest to see that the affair does not come out into the open. By the way, I have been charged to put you under a promise of the strictest silence. If a single word of this comes out, they will no longer feel themselves bound by the agreement.”

I tried again:

“Can’t we defend ourselves? He cut me off short.

“There’s no point,” he said.

“It’s better for one to die than for all of us to be killed in a shooting affray. Anyway, we’ve practically no ammunition.”

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, official statements declared, had died from complications resulting from injuries sustained while on active service. His State Funeral which followed soon after, the centre-piece of which was a wreath sent by the Fuhrer, was filmed for propaganda purposes.

It was to be his final contribution to the regime he had served so loyally but latterly come to despair of and even hate.

Winston Churchill, the man who had so often been at the sharp end of the Desert Fox’s cunning was to pay his own and sincerely held tribute:

A splendid military gambler his ardour and daring inflicted grievous disasters upon us but he deserves the salute which I made him in the House of Commons in January 1942, when I said of him:

""We have a very daring and skillful opponent against us , and may I say across the havoc of war, a great General.He also deserves our respect because, although a loyal German soldier, he came to hate Hitler and all his works, and took part in the conspiracy to rescue Germany by displacing the maniac and tyrant. For this he paid the forfeit of his life.”

Share this post: