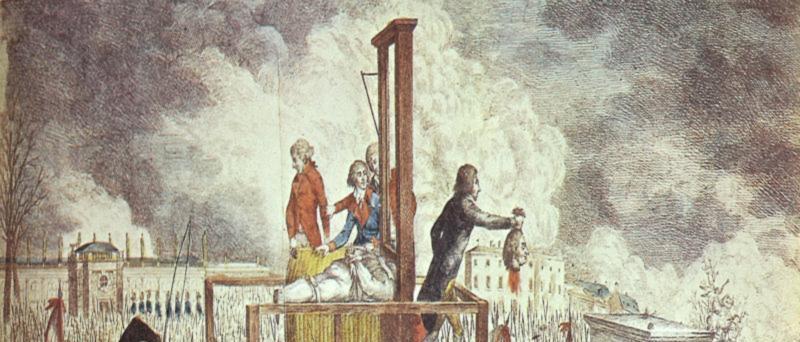

Execution of King Louis XVI

Posted on 4th February 2021

On 21 June 1791, while the National Assembly in Paris toiled long into the night over the articles of a new constitution, King Louis XVI along with his Queen Marie Antoinette and their children fled the city in plain clothes the curtains of their carriage tightly drawn. Their destination was the royalist stronghold of Montmedy from where they would be safely delivered into the hands of Marie Antoinette’s brother Leopold, Emperor of Austria. But their escort never arrived and stopped in the town of Varennes by the local postmaster who recognised the King from his image on recently issued paper money they were arrested and ignominiously escorted back to Paris. It was now clear to many that the King could no longer be trusted – the Bourbon Monarchy had reached the end of the road.

In September King Louis XVI was deposed and a Republic declared, soon after he would stand trial for his life accused of treason. Found guilty his fate now lay in the hands of the new National Convention. Passions ran high and the extremists among them Robespierre and Saint Just demanded his immediate execution though there were moderates who merely argued for exile. When the vote finally came it was closer than anyone could have imagined. While 361 Deputies were in favour of execution, 360 had opposed it – Louis XVI, the former King of France, had been condemned to death by just a single vote.

At his own request Louis was accompanied the journey to his place of execution by an English priest Henry Essex Edgeworth who had to all intents and purposes become the Royal Family’s confessor. This is his account of that fateful carriage ride and the maligned ‘Louis Capet’s’ final few hours:

"The King, finding himself seated in the carriage, where he could neither speak to me nor be spoken to without witness, kept a profound silence. I presented him with my breviary, the only book I had with me, and he seemed to accept it with pleasure: he appeared anxious that I should point out to him the psalms that were most suited to his situation, and he recited them attentively with me. The gendarmes, without speaking, seemed astonished and confounded at the tranquil piety of their monarch, to whom they doubtless never had before approached so near.

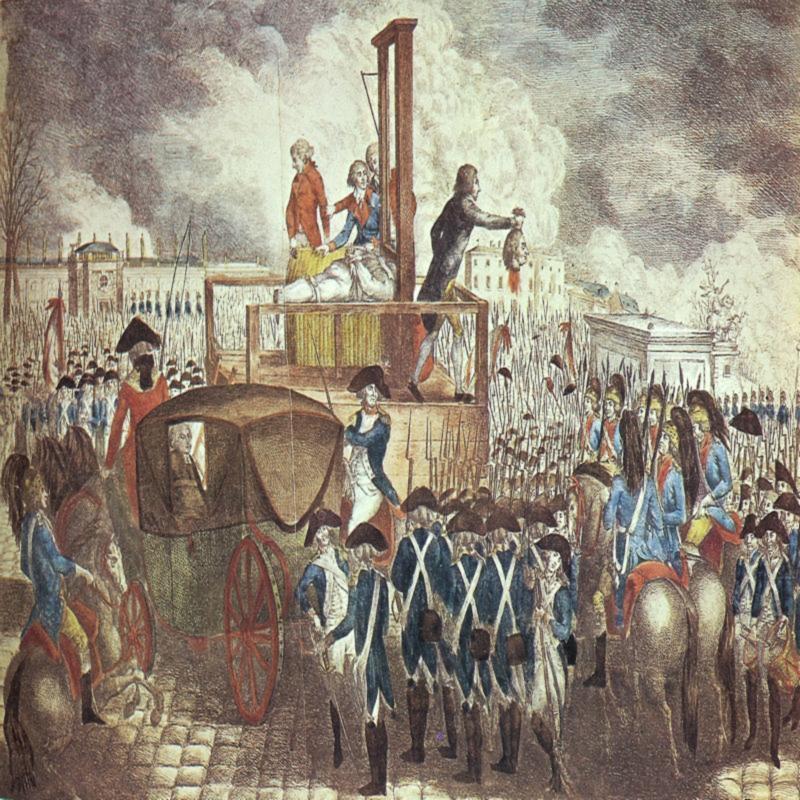

The procession lasted almost two hours; the streets were lined with citizens, all armed, some with pikes and some with guns, and the carriage was surrounded by a body of troops, formed of the most desperate people of Paris. As another precaution, they had placed before the horses a number of drums, intended to drown any noise or murmur in favour of the King; but how could they be heard? Nobody appeared either at the doors or windows and in the street nothing was to be seen, but armed citizens - citizens, all rushing towards the commission of a crime, which perhaps they detested in their hearts.

The carriage proceeded thus in silence the Place de Louis XV, and stopped in the middle of a large space that had been left around the scaffold: this space was surrounded by cannon, and beyond, an armed multitude extended as far as the eye could reach. As soon as the King perceived that the carriage had stopped, he turned and whispered to me, ‘We are arrived, if I mistake not.’ One of the guards came to open the carriage door, and the gendarmes would have jumped out but the King stopped them and leaning his arm on my knee, ‘Gentlemen,’ said he, with the tone of majesty, ‘ I recommend you this good man; take care that after my death no insult be offered to him – I charge you to prevent it.

As soon as the King had left the carriage, three guards surrounded him, and would have taken off his clothes, but he repulsed them with haughtiness- he undressed himself, untied his neck-cloth, opened his shirt, and arranged it himself. The guards, whom the determined countenance of the King had for a moment disconcerted, seemed to recover their audacity. They surrounded him again, and would have seized his hands. ‘What are you attempting?’ said the King, drawing back his hands. ‘To bind you,’ answered the wretches. ‘To bind me,’ said the King with an indignant air. ‘No, I shall never consent to that: do what you have been ordered, but you shall never bind me.’

The path leading to the scaffold was extremely rough and difficult to pass; the King was obliged to lean on my arm, and from the slowness with which he proceeded, I feared for a moment that his courage might fail; but what was my astonishment, when arrived at the last step, I felt that he suddenly let go my arm, and I saw him cross with a firm foot the breadth of the whole scaffold; silence, by his look alone, fifteen or twenty drums that were placed opposite to me; and in a voice so loud, that it must have been heard it the Pont Tournant, I heard him pronounce distinctly these memorable words: 'I die innocent of all the crimes laid to my charge; I Pardon those who have occasioned my death; and I pray to God that the blood you are going to shed may never be visited on France.'

He was proceeding, when a man on horseback, in the national uniform, and with a ferocious cry, ordered the drums to beat. Many voices were at the same time heard encouraging the executioners. They seemed reanimated themselves, in seizing with violence the most virtuous of Kings, they dragged him under the axe of the guillotine, which with one stroke severed his head from his body. All this passed in a moment. The youngest of the guards, who seemed about eighteen, immediately seized the head, and showed it to the people as he walked round the scaffold; he accompanied this monstrous ceremony with the most atrocious and indecent gestures. At first an awful silence prevailed; at length some cries of 'Vive la Republique!' were heard. By degrees the voices multiplied and in less than ten minutes this cry, a thousand times repeated became the universal shout of the multitude, and every hat was in the air."

Share this post: