Fall of Constantinople: Ending Byzantium

Posted on 3rd June 2021

Constantinople was the capital of the ‘Eternal’ Byzantine Empire and the glittering jewel of the Christian world. It was to here in 324 that the Emperor Constantine the Great had transferred power from Rome and first established Christianity as the religion of Empire facilitating its spread across the Western world.

It was also the Gateway to the East and had long been a thorn in the side of the Ottoman Empire, not because the Ottomans feared it but because it was the bridge between East and West and was believed to contain great wealth which they envied. They also resented this beacon of Christianity in the heart of their Islamic World, one which served as a place of refuge for apostate and infidel alike.

Situated on the Bosphorus at the far end of the Hellespont, Constantinople separated the Aegean Sea from the Sea of Marmara and surrounded by water on three sides and defended by a series of high walls on its landlocked western side it was not only a place of great strategic value but a formidable obstacle to any would be assailant.

Despite many previous attempts to do so it had only ever been captured once before, in 1204 by Western Crusaders and then more by deception than by force but the ruthlessly ambitious Sultan Mehmed II believed he could succeed where others had failed.

The 21-year-old Mehmed, an abusive and violent young man who had only recently been restored as Sultan, his arrogance having seen him briefly deposed, was neither popular with his people nor within his own Court though both were to revel in the glory of his triumph and profit from his conquests.

His father, Murad II, had unsuccessfully besieged Constantinople in 1522 but circumstances had changed since then, and Mehmed was confident that with the right preparation he would not suffer a similar fate.

The Ottoman’s had for many years been building fortresses with the intention of hemming in the city and choking off its supply lines, but they could do little about its access to the sea. Mehmed sought to change that and had constructed a second fortress on the European shore of the Bosphorus giving him control of the sea traffic to and from Constantinople. He had also stationed an army to prevent reinforcements reaching the city via Greece and built new roads and bridges to facilitate the passage of his heavy guns.

The fact that Mehmed was able to do this unimpeded indicated just how by 1453 the Byzantine Empire was a shadow of its former self and that the Emperor Constantine XI wielded little power outside the walls of the city itself. The historian Cedomilj Mijatovich wrote.

“The nation had become an inert mass without initiative and without will. Before the Emperor and the Church Prelates it grovelled in the dust; behind them it rose up to spit at them and shake its fist. Outward polish and dexterity replaced true culture. Both the social and political bodies were alike rotten and the spirit of the nation languid. Selfishness placed itself on the throne of public interest and tried to cover its hideousness with the mantle of false patriotism.

His spy network remained effective however, and he was well aware of the Sultan Mehmed’s intentions and that the building of yet another fortress was just a precursor to a full-scale assault on Constantinople itself.

He dispatched a series of increasingly desperate letters to the Pope in Rome pleading for military assistance most of which went unanswered; and it was to be divisions between the Orthodox Christian Church in the East and the Roman Catholic Church in the West and its indifference to the formers plight, that were to seal the Byzantine Empires fate every bit as much as the Army of Islam.

Constantine XI, of the Greek-Serbian Palaiologos Dynasty had only been Emperor for four years, though he had previously served as Regent and unlike many of his predecessors as Emperor he was a soldier and acknowledged as a practical plain-spoken man even if much of his short reign had been taken up with arcane and labyrinthine disputes with the Vatican in Rome.

Constantinople still considered itself the heart of Christendom and despite being militarily weak it’s very effective and wily Diplomatic Service fought hard to maintain its status. Likewise, the more powerful Roman Catholic Church believed itself to be the one true faith and had long tried to impose a union upon the Church in the East but their attempts to do so had been dismissed with such contempt by the Byzantines that it had created a sense of bitterness and mistrust between the two contending strands of the same religion.

It was only now aware that Mehmed was preparing to assault the city that in December 1452, Constantine XI at last agreed to such a union reaffirming the decision taken at the Council of Florence thirteen years earlier but few in Rome any longer believed him. Earlier comments such as that by the Grand Duke Lucas Notaras that “It is better to see in the city the power of the Turkish turban than that of the Latin tiara” were not easily forgotten or forgiven.

Constantine’s decision at last made Pope Nicholas VI realise the gravity of the situation and he now did his best to rally support, but his appeals were to fall largely upon deaf ears – Europe it seemed had its own problems. So the Pope’s attempts to raise a Crusader Army to defend the last Christian bastion in the East came to nothing. Constantinople would have to fight on almost alone, the only city that rallied to its support in any strength was its main trading partner Genoa and in January 1453, the noted Condottieri Giovanni Giustiniani arrived with 700 troops. Venice also sent ships and a small number of men while the Papal contribution was a mere 200 troops under the command of Cardinal Isidore.

In the meantime, the Byzantines tried to do what they had done since the time of Attila the Hun and buy themselves out of trouble, but Mehmed refused to negotiate with their Ambassadors who were returned to the city minus their heads.

By April 1453, Mehmed had amassed an army of 150,000 men to the western land-locked side of the city while his navy blockaded what was known as The Golden Horn to prevent access by sea. His own ships, however, were prevented from entering the harbour by the boom drawn across it.

Constantinople was defended on its landward side by 200 external and internal fortifications known as the Theodosian Walls but with only 7,000 troops at his disposal it was not possible for Constantine to man both the outer and inner walls. The decision was made to man the outer walls but so thinly spread were his forces that Constantine issued an appeal to the city’s male population to form a militia but of the 25,000 males the census had revealed to be of military age only 200 came forward. Few it seemed were willing to take up arms in their own defence. Still the walls were strong, and Constantine hoped that they could hold out long enough to prick the consciences of the western powers forcing them to come to his assistance.

On 5 April, an attempt was made to destroy the blockading Ottoman Fleet with fire-ships. It failed but caused enough confusion for ships carrying valuable supplies and in one case over a 1,000 Genoese reinforcements to break through. Constantine immediately ordered that the Genoese be marched along the walls in full armour to show the Turks just how many men he now had. It was bravado of course, but it seemed to work for Mehmed now hesitated to attack and it wasn’t until the 18 April that he finally ordered a simultaneous large scale assault on the Theodosian Walls and the Boom across the Golden Horn.

Howling at the top of their voices the Turks rushed the trenches before the outer walls. A witness described the scene:

“The reports of muskets, the ringing of bells, the clashing of arms, the cries of fighting men, the shrieks of women and the wailing of children produced such a noise that it seemed as if the earth trembled. Clouds of smoke fell upon the city and the camps and the combatants could no longer see one another.”

Giustiniani had prepared well however, and the attackers were met with a hail of crossbow bolts, missiles and Persian fire. The fighting was fierce and bloody but unable to make any progress and with casualties mounting the Turks were forced to abandon the assault. Meanwhile, the Byzantine Fleet under the command of the Duke of Notaras had thwarted the attack on the Boom.

Mehmed was furious and his ire only increased upon learning that a number of ships had eluded the blockade to deliver valuable supplies and a small number of reinforcements. He expressed his anger by having 40 captured Italian sailors impaled before the city walls. Giustiniani retaliated by having 200 Turkish prisoners beheaded in full sight of the enemy and their bodies tossed into the ditches below.

Further attacks followed over the coming days, but little progress could be made. On May 7, Mehmed launched 30,000 men against the St Romanus Gate the fourth of six such large gates that permitted access to the city, but it was again beaten back with great loss of life as was an even larger attempt five days later.

On May 18, Mehmed tried again this time using a Helenopolis or high wooden tower that allowed its occupants to reign down a deadly fire upon the defenders on the ramparts. Giustiniani did not hesitate to have barrels of gunpowder rolled into the trenches and detonated destroying the tower and killing hundreds of Turks causing Mehmed to exclaim, “What I would not give to win that man over to my side.” He would later try and bribe him to do so but it came to nothing.

With his large bombards having failed to either demolish the towers or force the gates and his troops having been repulsed again and again work now began to mine beneath the walls instead. Aware of this the engineer Johann Grant suggested to Giustiniani that they counter-mine and under his command the Byzantines were able to frustrate Ottoman attempts to bring down the walls as he introduced smoke in the tunnels to suffocate the Turkish miners or let in water to drown them. When these failed, they engaged in hand-to-hand fighting with knife, club and axe to thwart them.

Such failures disheartened the Turks as did the rumour that a Hungarian Army was advancing from the north and a Papal Fleet from the south. Military defeat did not yet beckon for the Turks but a loss of will did and with supplies running short the threat of starvation was never far away.

On 21 May, Mehmed sent emissaries to negotiate the surrender of the city and the offer was a generous one; if the Emperor agreed to hand over the keys and be subordinate to the Sultan then he could remain and the people would be spared. But if not, the city would be sacked and all within sold into slavery or put to the sword. The offer was summarily rejected.

Earlier a ship had eluded the blockade with orders to locate the Papal Fleet that was supposedly sailing to the city’s rescue. On 23 May it returned to report that no sighting had been made and with no sign of a Hungarian Army either it seemed the last hope of relief was gone. As if this wasn’t bad enough. Mehmed acting on the advice of a Genoese merchant some of whom had sided with the Ottomans constructed a runway across a mile or more of land to a stream that led into the Golden Horn. The runway he then had greased so that ships could be hauled across it. This was followed by a bridge 2,000 feet long and 8 feet wide that allowed for reinforcements to be brought over from the north shore.

When the 70 or so ships of the Ottoman Fleet appeared in the Golden Horn despair gripped the city, they could now be attacked from both land and sea. It seemed the end was nigh, and it was suggested that the Emperor should flee at once. But Constantine was adamant he must remain. He told his Council; “I thank all for the good advice you have given me but how can I leave the Churches of Our Lord and His servants the clergy and the throne, and my people in such a plight? What would the world say about me? Never, never will I leave you! I am resolved to die here with you.”

The Emperor’s words inspired the Byzantines to fight on but the situation remained no less hopeless.

Mehmed who had also learned the rumours of a relieving force were false now moved his enormous siege guns closer to the city walls and began to mass his troops for an assault but hesitated to use them hoping that the bombardment from both land and sea would at last bring Constantine to his senses. It did no such thing and Mehmed’s patience was wearing thin. With a plan in place, he decided to finish it:

The Turkish Fleet would assault the sea walls pinning down the defenders so they could not reinforce those manning the landward defences. In the meantime, the army would assail the Theodosian Wall in three places either side of the Adrianople Gate, the Rhegium Gate and the Third Military Gate but the focus would remain the Romanus Gate as before and the area between it and the Golden Gate. The attack would not cease until victory had been secured and would involve the entire Ottoman Army. Mehmed told his Senior Commanders: “I have decided to engage successively and without halt one body of fresh troops after another until harassed and worn out the enemy will be unable further to resist.”

It was clear to those defending the city that the moment of decision had come but with fewer than 4,000 troops remaining there was little Giustiniani could do but pray. Constantine thought otherwise and now ordered that all the monks in the city be armed and pressed into service. They would have to defend one of the gates. But he too looked to Divine intervention declaring a day of prayer and attended a Salvation Mass in the Church of Hagia Sophia.

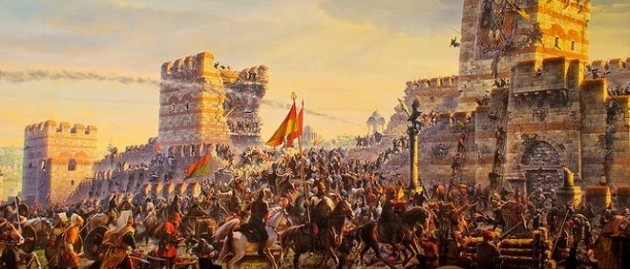

The attack began just after midnight on 29 May, as thousands of ill-disciplined Azaps, irregular troops who fought for plunder and mercenary Turkomen surged towards the Meseterchion Gate, a weak spot in the defences where ditches had been hastily dug and barricades erected. Giustiniani, in command of 2,000 mostly Genoese troops took the full brunt of the attack. After two hours of fierce hand-to-hand fighting, they repulsed the Turks but at great cost to both the enemy and themselves. They were exhausted but there was to be no respite and neither could they retreat for the gates had been locked behind them - they would have to stand and fight where they stood.

Mehmed now ordered in his cavalry who with horns blaring and flags flying paraded beneath the walls of the city before dismounting and attacking on foot. Giustiniani once again justified his reputation as a gallant soldier now as in the thickest of the fighting he rallied his rally his troops time and again until the Turks first held up at the breaches were then forced back to catcalls and howls of derision from the walls above. But inroads were being made elsewhere.

Some Turkish troops had gained entry to the city through the unlocked Kerkoporta Gate and Constantine who was himself directing the attempt to eject them had been unable to prevent the Islamic flag being raised making it appear that at least part of the city had already fallen.

Fearing the people might panic at the sight of the flag he now ordered them to pray for the intercession of the Virgin Mary whom it was believed had come to their rescue in 1522, and thousands of people now packed into the Church of Hagia Sophia - panic was avoided and still the city held out.

With the great chain that had prevented his ships from entering the harbour now circumvented soldiers and sailors from the ships blockading the harbour were now able to land and begin fighting their way towards the city where they soon found themselves in combat against the many monks now in arms.

Believing that the city was about to fall Mehmed seized his chance ordering into the attack his elite Janissaries (Christians who had been captured at an early age and raised to be warriors) riding before them and exhorting them to attack and conquer.

Again, Giustiniani and his Genoese stood their ground and initially repelled the attack but sometime during the fighting he was wounded. It is possible that his nerve at last failed him for despite being conscious and able to stand he ignored the pleas of the Emperor to remain and instead demanded to be taken into the city for treatment. Witnessing their leader leaving the scene the Genoese panicked and followed him through the now unlocked gate.

Constantine and his Byzantines tried to fill the gap that had been created by the Genoan’s departure but with the Turks flooding into the city the situation was fast becoming hopeless. Constantine with the few troops remaining to him led a last desperate counterattack but was killed in the fighting. His body was never recovered.

Pockets of resistance continued in places but for the most part those defending the city discarded their weapons and hid, others sought sanctuary in one or other of the many churches and religious houses, some boarded ships in a desperate attempt to make for the open sea but few escaped.

For two whole days the Turks rampaged through the streets of Constantinople destroying at will, taking all they could and inflicting a fearful massacre upon the populace. A Dominican scholar Leonard of Chios who witnessed the atrocities wrote that:

“All valuables and other booty looted from the city were taken to the Ottoman Camp along with as many as sixty thousand Christians who had been captured. The crosses which had been placed on the roofs and walls of churches were torn down and trampled upon. Women were raped, virgins deflowered and youth forced to take part in shameful obscenities. The nuns left behind, even those who were obviously such, were disgraced with foul debaucheries.”

Another declared that:

"Nothing will ever equal the horror of this harrowing and terrible spectacle. People frightened by the shouting ran out of their houses and were cut down by the sword before they knew what was happening. And some were massacred in their houses where they tried to hide, and some in churches where they sought refuge. The enraged Turkish soldiers gave no quarter.”

The Ottoman official Tursun Beg took a more benign view, however:

“After having completely overcome the enemy, the soldiers began to plunder the city. They enslaved boys and girls and took silver and gold vessels, precious stones and all sorts of valuable goods and fabrics from the imperial palace and the houses of the rich. Every tent was filled with handsome boys and beautiful girls.”

Mehmed, who had allowed his army three days of plunder as promised entered Constantinople to the acclaim of his troops, but he was shocked by the sight of it and feared for its great structures. He ordered the violence to cease and declared that those Christians who had avoided capture or paid a ransom could return to their homes unmolested.

Meanwhile, in the West Christian rulers shook their heads in disbelief and wrung their hands in despair. The Pope demanded a new Crusade to re-conquer the city for Christ, but nothing came of it, the city that could not fall had fallen, the Eternal Empire had ceased to be, and Islam was in the ascendant.

Mehmed remained determined to expand his Empire even further and in 1456 laid siege to the city of Belgrade but was defeated by the Hungarian Army of John Hyundai. Even so, Greece, Serbia and much of the Balkans were conquered and the march west of the Ottoman Empire wouldn’t finally be halted until defeated at the Siege of Vienna in 1683.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, War

Share this post: