Field of the Cloth of Gold

Posted on 7th January 2021

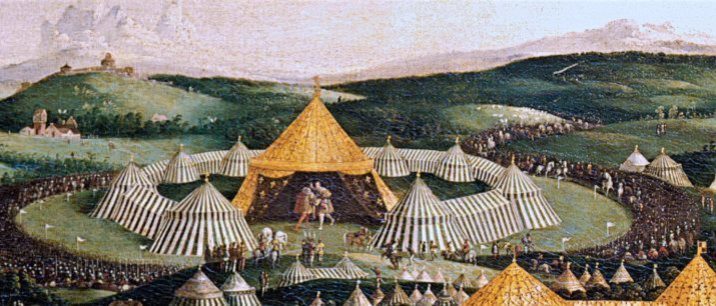

For two weeks in June 1520, a meeting took place between Henry VIII of England and Francis I of France incomparable in its grandeur and no less boundless in its ambition. It was an extravaganza of display and excess so great as to leave no observer in any doubt as to the power and might of their respective majesties. It was also the vanity of Kings as empty of achievement as it was vacuous in delivery – it was the Field of the Cloth of Gold.

The architect of this pageant of was Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, a man of remarkable abilities who would dominate English political life for more than twenty years and work tirelessly to secure the Tudor Dynasty and carve out for it a place in European affairs.

He had been born in 1473, in the market town of Ipswich to a family which though far from poor were of humble origins. His father had in fact been a prosperous dealer in livestock and trader in meats hence the insult ‘The Butcher’s Son’ that soon attached itself to Wolsey and though rarely spoken in public would remain a popular refrain among his enemies.

Wolsey’s father had been prosperous enough to send his son first to a Church School and later to University to study theology at Magdalene College, Oxford, where he received his Doctorate before leaving to be ordained a priest in March, 1496 but the young Thomas Wolsey was to prove himself less a Man of God than he was a bureaucrat and administrator without peer becoming the Executor of the Estate of Sir Richard Nanfan; where his reputation as a tireless worker with an impressive grasp of detail for whom the hum-drum was no burden saw his stock rise rapidly bringing him to the attention of King Henry VII, a man not adverse himself to poring over the accounts and annotating the ledger books.

In 1507, Wolsey was appointed Royal Chaplain where again his workload was mostly administrative, it was his first step on the path to power and few who knew him at the time doubted he would get there.

On 21 April 1509, the old King died to be succeeded by his seventeen-year-old son Henry VIII who keen on jousting, the hunt, and his pursuit of the ladies had little interest in the day-to-day administration of his realm. But the young Henry had inherited his predecessor’s advisors who expected the same sober and studious approach to Kingship from the son as they experienced from the father and none more so than his Chancellor, the fussy and meddlesome Bishop William Warham.

Being King meant politics and paperwork, administration which wearied a young man eager to indulge his passions but there was someone willing to lessen the burden and who was not shy in letting him know so.

Wolsey had been appointed Almoner, or the man of the cloth responsible for the distribution of alms to the poor which brought with it a place on the Privy Council and to the attention of a young King who desperate to prove himself on the field of battle had re-asserted his claim to the French Crown and had determined upon a policy of aggression to attain it.

Many of those on his Privy Council opposed any war, in particular Bishop Warham who insisted that they were expensive, divisive, and had no guarantee of success. Wolsey, however, would be a vocal advocate of the King’s war policy and would speak in favour of it time and time again - his support did not go unnoticed.

When war with France finally came in late 1512 it was to be Wolsey’s success in providing the funds to supply an army in the field that played a significant role in Henry’s victory at the Battle of the Spurs in August 1513, and his subsequent capture of two French cities.

It had been a triumph for Henry if less than he had hoped for, but it would be Wolsey once again who would prove his worth negotiating a peace treaty favourable to English interests. In fact, so important had Wolsey become that when an exasperated and exhausted Bishop Warham resigned as Chancellor in 1515, Wolsey was the obvious candidate to replace him.

Thomas Wolsey’s talent for administration and his carefully honed diplomatic skills were surpassed only surpassed by his desire for great wealth and unbounded ambition as he accumulated titles and positions of authority as if they were a contagion becoming in quick succession Canon of Windsor, Bishop of Lincoln, and Bishop of Durham as well as his position on the Privy Council. The same year as he replaced Bishop Warham as the King’s Lord Chancellor, he was made a Cardinal by Pope Leo X.

With power came the money and Wolsey was neither shy in accepting it nor of extorting it where he deemed it necessary, and he spent lavishly – if the King had the throne then his Chief Minister had the palace.

But not for long, Henry would soon dispossess him of the greatest of these, Hampton Court compensating him with a residence more fitting to his subordinate status - Wolsey was delighted, of course.

Despite some friction between the two men Wolsey very soon cemented his position as the King’s essential man with his strong grip on domestic affairs, contacts abroad, and adroit diplomacy acquiring for England a cachet on the European stage that it had never known. He certainly impressed the Pope who would appoint him Papal Legate with plenipotentiary powers able to speak with Papal authority, an authority he soon began to wield without recourse to the Vatican and if he wasn’t exactly the Pope of Northern Europe it didn’t stop him behaving as if he were one. And he would use that power to shape a Europe with England at its centre.

He had already effectively co-opted what became known as the Treaty of London , a non-aggression pact between the leading powers of Europe intended to be a bulwark against any further Ottoman aggression from the East, now he would bring two old enemies together at the table not just of good food and fine wines but of peace and co-operation.

But neither Henry VIII nor the French King Francis I could claim to be the most powerful ruler on the Continent, that title belonged to Charles V the Hapsburg ruler of Burgundy, the Netherlands, Austria, Bohemia, large parts of Germany, much of Italy, and Spain who in June 1519 had been elected Holy Roman Emperor defeating the candidacy of Henry and Francis in the process.

Wolsey was aware of this and his diplomacy in bringing England and France together in amity was to show that old rivals could work in a partnership of mutual self-interest against any external threat or enemy, by which he meant Charles V every bit as much as he did the Ottoman Turks. As has so often been the case since his ambitions were couched in the meaning of good intentions – to bring perpetual peace to a Christian world founded on Christ’s teaching of love for your fellow man.

In truth, he knew that England was in no position to take the lead in such a grand design when compared to the leading powers of Europe it was insignificant. France alone, with its greater land mass had a population of 16 million to England’s 2.5 million with far greater resources, far greater wealth, and far greater access to tax revenues. Not for the last time in its history, England would be punching above its weight. Indeed, it is a tribute to Wolsey’s charisma and persuasive manner that he convinced Francis I to participate at all.

English preparations for the much-anticipated meeting were thorough as one would expect organised as they were under the watchful eye of the omnipresent Cardinal, in particular its potential to be ruinously expensive but under his able management the Treasury coped with the strain unlike the many who would leave themselves close to bankruptcy following their participation.

The meeting was to take place at Balinghen near Calais and just inside English territory in France, a concession agreed to on the grounds that Henry had sailed across the Channel to be there – and everything at the Field of the Cloth of Gold was to be considered equal – though each would do their best to out-match the other.

The English had brought everything they required with them including 40,000 gallons of wine (about 4 pints per person per day) 14,500 gallons of beer (with the means to brew more) 9,100 plaice, 7,836 whiting, 5,554 sole, 2,800 crayfish, 700 conger eels, 370 oxen, and 2,500 sheep.

Prior to their departure from Dover the religious houses and stately homes of England were stripped of their silver wear, porcelain, and soft furnishings as decoration for the forthcoming event. If the English could not out-do their new French allies in deportment then they would do so in their accommodation bringing with them the materials to construct a brick and canvass castle in the perpendicular style adding the mirage of permanence to an event of transitory surrealism, so unlike the tents of the French, extravagant though they were.

Both Henry and Francis were accompanied by the greatest nobles of the land, the representatives of the church, by diplomats and laymen, lesser gentry, men-at-arms, their retinues, and of course their ladies. Both entourages were expected to number no more than 6,000 but it remains impossible to know if this was so, and their respective camps were raised equal distance from their meeting place soon to be known as the Field of the Cloth of Gold from the vast pavilions that had been erected and draped in silk with gold filaments sewn into the fabric.

On the morning of 7 June, the two King’s set off alone from their camps at the same time across land that had been levelled so that neither would be raised higher than the other. They rode at a trot and then at a gallop as if into combat before pulling aside at the last moment and embracing.

Both King’s saw themselves as Renaissance Princes and as warriors in the chivalric tradition; Francis, as the new Caesar; Henry as the reincarnation of his forebear Henry V, the victor of Agincourt. But they were very different men.

A little over 6’1” broad shouldered, bearded and with a shock of red hair and pale skin that glowed when exercised the 28-year-old Henry was full of bluster and manly bonhomie that could appear coarse when contrasted with the courtly manner of the younger, somewhat taller, slim-hipped figure of Francis, so graceful and elegant with the twinkle in his eye that charmed the ladies.

They were both at the peak of their physical and mental powers eager to compete both intellectually and in displays of athletic prowess but Henry, with perhaps more to prove, often appeared tense and ill-at-ease while Francis by comparison was relaxed, so much so that one morning riding alone to Henry’s camp he burst unannounced into the King’s bedchamber declaring to the barely awake Tudor Monarch: “My dear cousin, I come to you of my own free will, I am now your prisoner.”

It was a remarkable act of trust in the fidelity of an old foe, but a startled Henry responded with good grace laughing and embracing Francis before both King’s exchanged gifts. Henry would return the gesture a few days later minus the same impact.

With a giant fountain dispensing water and wine to the thirsty the ready availability of alcohol made for a lively atmosphere, but the drunkenness, brawling, and generally lewd behaviour that ensued tarnished the spectacle; and for all its grandeur the Field of the Cloth of Gold soon become a hive of hucksterism as peddlers, mendicants, charlatans and fraudsters descended upon it seeking to fleece the gullible and rob from the incapable.

The great and the good were spared such sights as might offend them in cordoned off areas while at the various sporting contests the English impressed in displays of archery and the French at wrestling; mock battles were organised for knights on foot in full armour, but the highlight remained the joust, the peak of chivalric endeavour in which not only the great nobles but both King’s participated, though not against each other. Although it was claimed that at one point during the proceedings Henry challenged Francis to wrestle and was worsted much to his chagrin.

In the evening Henry and Francis, along with their close retinues would dine together at a great feast where style and expensive silks not of armour was the order of the day. Prayers would be said, toasts made, and oaths to eternal friendship taken before the entertainment would begin – jugglers, acrobats, singers, and of course music and dancing where the ladies of both Royal Courts would take centre stage.

Some later claimed to have been offended by the forwardness and provocative manner of the French ladies, in particular their figure-hugging, low-cut dresses but it was a fashion soon to be adopted by their English counterparts.

Not everyone was fooled by the stage-managed amity on show however, the Venetian Ambassador wrote: “These two Sovereigns are not at peace, they hate each other cordially.”

Such festivities continued throughout except on a Sunday, the Lord’s Day, when frivolity and excess ceased, and all attended Church Service and spent their time in prayer and pious devotion.

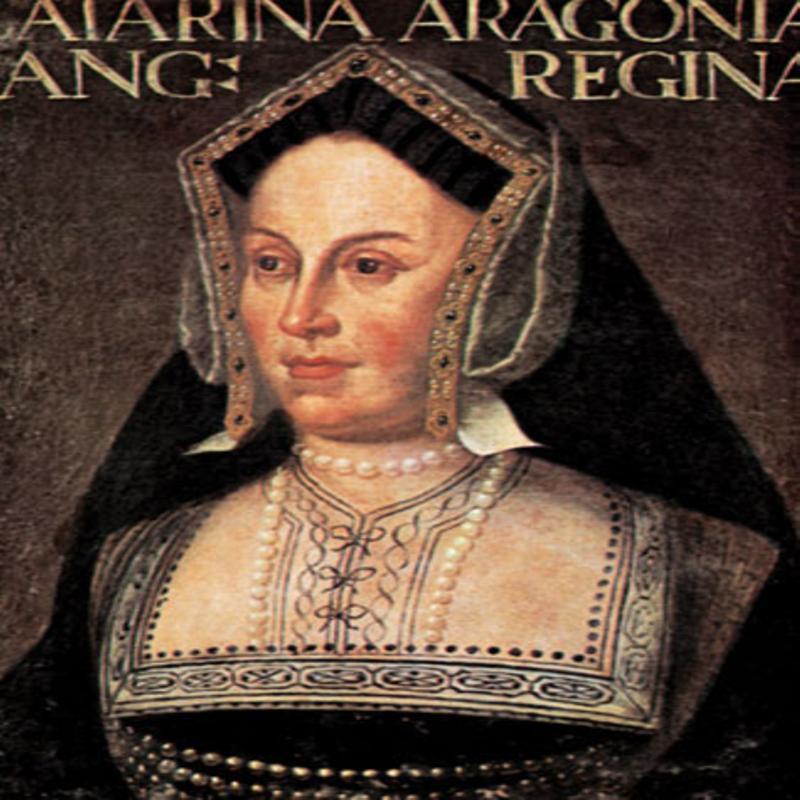

Sunday night passed with the two Kings dining quietly with the others Queen, Francis with the formal and reverential Catherine of Aragon, Henry with the plump, often sickly, but sweet-natured Claude of Brittany. Indeed, it is likely that it was during one of these meetings that Henry first encountered Anne Boleyn, a lady-in-waiting to Queen Claude, though he would not recollect having done so.

One man, who rarely partook of the festivities despite his regular attendance upon his Liege Lord Henry, was Cardinal Wolsey for whom the Field of the Cloth of Gold remained a political summit meeting of the utmost importance and much of his time was spent in tense negotiations with the representatives of the French King. In a grand ceremony Henry’s infant daughter Mary (who was not actually in attendance) was betrothed to the even younger French Dauphine. Their engagement was a personal triumph for Wolsey and delighted an English King who still harboured ambitions of a Tudor Monarch one day ruling France.

As the skies darkened and the proceedings at the Field of the Cloth of Gold ended an apparition appeared in the sky. Some would later describe it as a firework display, others that it was a smoke-like substance in the shape of the Tudor Welsh Dragon or the French Fleur-de-Lys but all agreed that it was a blessing from God.

As both camps packed up their chattels and departed the scene to go their separate ways it seemed as if peace had indeed broken out, but like so much of the pageant itself it was an illusion for little of any real significance had been achieved; there was no strategic plan, no programme for future cooperation, and no peace treaty had been signed merely a verbal agreement to remain friends. It soon became clear that Wolsey’s grand design to re-shape the political map of Europe had come to nothing and even the few protocols that had been signed lasted barely longer than it took for the ink to dry on the parchment.

The great Royal Pageant of the Field of the Cloth of Gold proved an empty vessel devoid of content and with no gains for either side.

Within weeks of their return to England at the invitation of Cardinal Wolsey, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V was to visit the Court of Henry VIII where evidently impressed by the force of the King’s personality and the wily charisma of the Cardinal he was seduced into believing that the future lay in partnership with an emerging and vigorous England.

Wolsey was quick to seize the opportunity of an alliance with the most powerful Monarch in Europe which may indeed have been his true intention all along given the rapidity with which all that had so recently gone before was relinquished; any agreements made with Francis I were renounced and the engagement of Mary to the French Dauphine broken off.

A little over two years after the Field of the Cloth of Gold and the pledge made before God of ‘Perpetual Peace’ between old foes - England and France were once more at war.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: