Flora MacDonald: The Reluctant Jacobite

Posted on 9th January 2021

She should have died in obscurity having lived an unremarkable life in a place as remote geographically as it was unheard of; but she was brought into the narrative of history by events and having had fame thrust upon her the page she wrote was to prove indelible.

Flora MacDonald was born in 1722, on the Island of South Uist in the Outer Hebrides a daughter of the Highland Clans, the MacDonald’s of Clanranald.

The Islands off the northern coast of Scotland of jagged cliff and narrow inlet, barren and windswept and surrounded by a treacherous sea stood in defiance of nature, majestic as if torn from the grasp of God against His will; but though grim, frightening and a place of dread to many they, bore deep into the heart and soul of their inhabitants. Flora was deeply attached to the place of her birth and when as a young girl her father died and her mother remarried, she declined the opportunity to leave. Instead remaining to immerse herself in the folklore of the place, reciting the poetry of the people, and becoming a fine singer of songs in her native Gaelic.

But if she would not go into the world then the world would come to her, and in September 1740, she was invited to stay with Lady Margaret MacDonald of Monkstadt in Edinburgh where she could continue her education. It remains uncertain if she accepted the invitation or for how long, but by 1745 she was back in the Hebrides. It was to prove a significant year.

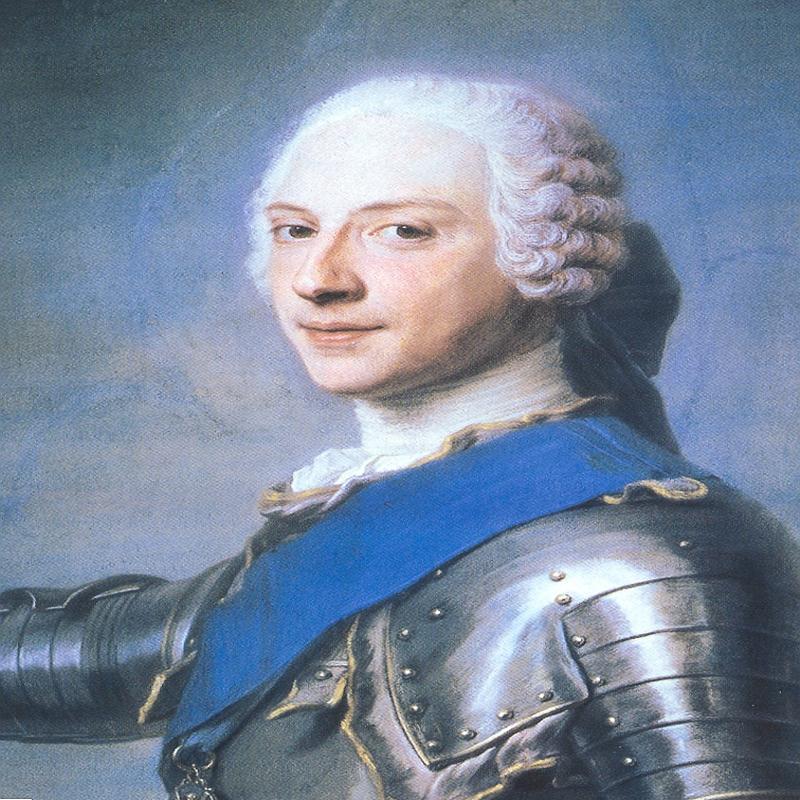

On 23 July 1745, Charles Edward Stuart landed at Eriskay with just seven companions and a small cache of arms to regain, he said, the throne of Britain for his father and to restore to Scotland and beyond the one true (Catholic) faith, but other than fine words and much sentiment he had little to offer those present to greet him. He told them to trust in God and the loyalty of his people, but his reception was less than enthusiastic. Indeed, news of the prince’s arrival which soon spread was not greeted with anything like universal approval.

Clan Chief Ranald MacDonald, who resided on the Island of Benbecula, was less than eager to be implicated in any anti-Hanoverian plot and had declined to come out in support of the Stuart claimant - the Islanders isolated, vulnerable to assault from the sea and with no hills or hinterland to retreat to were disinclined to commit to adventures of uncertain outcome, but he was willing to allow his son to commit to the Prince if he wished and along with other branches of the Clan as many as 500 MacDonald men were to fight for the Stuart cause constituting a sizeable proportion of what would be the Jacobite Army.

Despite such unpromising beginnings a series of unexpected victories saw the Jacobites clear much of Scotland of Hanoverian forces and march south to within 80 miles of London but no farther, and just 8 months after formally raising his Standard at Glenfinnan the Prince’s cause lay in ruins shattered upon the desolate moors of Culloden and thereabouts.

Following his defeat rather than try and rally his surviving troops, many of whom had not been present at the slaughter of Drumrossie Moor, he abandoned the Clans that had supported him and fled north with a price upon his head and the shadow of the noose around his neck. Accompanied by a small retinue of loyal supporters he hid out in caves and abandoned buildings becoming reliant upon strangers for his sustenance and safety.

Living in constant fear that he would be betrayed for the unprecedented reward of £30,000 that had been offered for information leading to his arrest he was in despair and drinking heavily. His love of the bottle had already been noted but now it seemed it was his only solace. He was not just a hunted but a haunted man, and it was feared that he would break under the strain.

By June he and his entourage had escaped as far north as Benbecula where the 24-year-old Flora was resident.

The island was under the titular control of the Hanoverians but with no troops present they were reliant upon a local Militia to impose their authority many of whom though they had not fought for were sympathetic to the Jacobite cause. This at least offered a little respite and a glimmer of hope for the refugees but opinion on the Island remained divided and the reward was a great temptation.

A naval blockade had seen the noose tightening while knowing who they could trust was a constant source of uncertainty and trepidation.

One of the Princes companions was Captain Conn O’Neill, a distant relative of Flora’s who had met her on several occasions and knew her to be calm and good natured. He thought her a woman they could trust.

When he took Flora to visit the prince and asked for her help, she was reluctant to become involved. She had taken little interest in the rebellion and knew that to aid the fugitive would be an act of treason undertaken at the risk of her own life. It was only upon meeting the prince, malnourished, dishevelled, despondent, and tipsy that she changed her mind. She did so out of a sense of common decency rather than any expression of political or dynastic affiliation. But from this moment on she took charge, the plan of escape would be hers, she would organise it, and she would facilitate it.

With the prince disguised as Flora’s Irish maid Betty Burke, they would charter a boat and row to the Isle of Skye where support for the Jacobite cause was stronger. Once safely on Skye the prince would hide out until the opportunity came to continue onto Raasay, from where he could take ship for the Continent and safety.

The Commander of the local Militia just happened to be Flora’s stepfather Hugh MacDonald, not a man in whom she could confide but one she knew would issue her with a pass to the mainland for herself, a manservant, a maid, and a crew of six boatmen with few questions asked.

The prince may have been clean shaven and slim hipped, but he was also tall and ungainly and did not make a convincing woman. It also made finding clothes to fit him problematic but with his rouged cheeks and twee bonnet he did not go unnoticed and turned a few heads:' Oh! See that strange woman, her big wide steps! What a bold slattern she is! One of a giant race for sure'. His trying to keep his long dress from trailing in the mud whilst also acting the part of an oversized and compliant Irish maid was the cause of much mirth. His own thoughts on the matter went unrecorded.

Leaving on 27 June with the pass from her stepfather there was little need for secrecy and though the atmosphere was fraught with tension the journey itself was uneventful except for a choppy sea that rendered some less than leaden bottomed.

Having reached the Isle of Skye the prince was ushered into hiding whilst a network of support and safe houses was established. Having done everything that Flora believed was required of her she made her departure as to remain longer than expected might be thought suspicious. Before leaving the prince thanked her in person promising she would be suitably rewarded upon his return.

But the Stuart presence would never again cast its shadow upon Scotland’s shores and though their farewell had been heartfelt and beset with tears of joy and relief she would never see nor hear from him again.

It wasn’t until September that a French Frigate was at last despatched to pick up the prince and transport him to safety by which time it was more in the Hanoverian’s interests to see him gone than bring him to trial.

Meanwhile back on Benbecula, Flora was soon disobliged of any notion that she may have got away with it. The boatmen, sworn to secrecy soon broke their oath and spoke loudly of the unusually tall and masculine woman who had been present in their boat.

Flora was arrested on suspicion of having aided in the escape of the traitor Charles Edward Stuart and taken south and imprisoned in the Tower of London along with other suspected Jacobites. But unlike her fellow captives who elicited little sympathy Flora was much spoken of and in her case a willingness to concede the benefit of doubt prevailed. Those who met her were intrigued and seduced by her charms. She would soon become a cause celebre.

She was taken before the victor at Culloden, the Duke of Cumberland, whose paunchy demeanour, and amiable bonhomie belied the ruthlessness that earned him the title ‘Butcher Cumberland’, Flora was not intimidated but instead conducted herself with grace and good humour answering his questions with a calm reassurance. When he demanded to know why she had knowingly betrayed her Sovereign, she insisted that she had acted only out of Christian charity declaring: 'I should have done the same for you Your Royal Highness had you been in like need.' The Duke was suitably impressed.

It was soon widely acknowledged that she had not acted out of malice and posed no threat to the Hanoverian State and so from time-to-time she was permitted to live outside of the Tower of London under the watchful gaze of Lady Primrose in whose care she was left. On 17 June 1747, she was released from captivity under the General Amnesty promulgated for those remaining Jacobites who had not been brought to trial and returned to Scotland.

If she thought it was to a quiet life, she was mistaken for she was now famous and unusually for any conflict a heroine to both sides - to the Jacobites for her courage and devotion to the lost cause, to the Hanoverians for her daring, kindness, and humanity.

On 6 November 1750, she married Allan MacDonald, an Officer in the British Army and for the next two decades lived the sober life of devoted wife and mother bearing him seven children. Her domestic bliss interrupted only by the curious who would gawp from afar or those prominent people who paid attendance upon her. One such visitor in 1773 was Dr Samuel Johnson of dictionary fame who wrote of her: 'She was a woman of middle stature with soft features, gentle manners, a kind soul, and an elegant presence.'

In 1774, Flora and Allan left Scotland for North Carolina just in time for them to become involved in the American War of Independence where her husband serving in the British Army was taken prisoner leaving Flora to fend for, herself. It was to prove a traumatic time particularly when her house was destroyed, and her possessions stolen.

Flora yearned to return home to the place she loved but it wasn’t until 1779 when her husband was released from captivity that they were able to take ship for England but even then, it was to prove anything but trouble free. Attacked by pirates during the voyage Flora refused to hide below decks and was badly injured in the fighting.

Destitute but well-connected Flora lived with relatives until 1784 when she and her husband were once more able to move into the family estate of Kingsburgh on the Isle of Skye where they remained until her death on 4 March 1790, aged 68.

Flora passed into history as she had lived as the Reluctant Jacobite. The words that adorn her memorial at Kingsburgh are those penned by Dr Johnson:

'Flora MacDonald, Preserver of Prince Charles Edward Stuart. Her name will be mentioned in history if courage and fidelity be virtues spoken of with honour.'

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: