Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole

Posted on 22nd February 2021

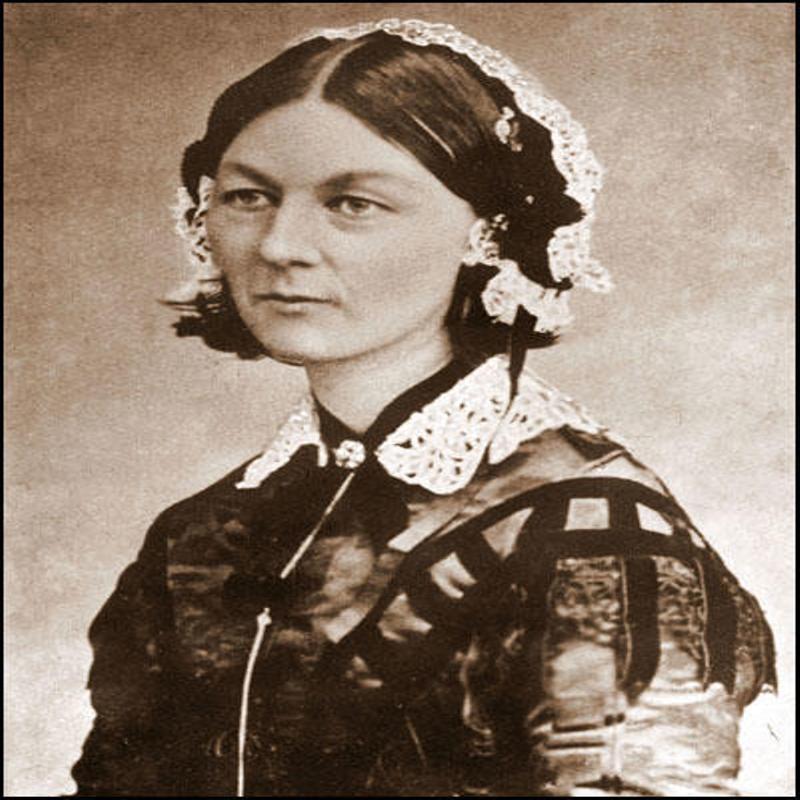

Florence Nightingale was born on 12 May 1820, in Florence, Italy, the city after which she was named. Her family were wealthy and well-connected and not long after her birth they moved back to their stately home Embley Park in Wellow, Hampshire.

Even though little more was expected of the young Florence other than she be a lady and marry well her father ensured she received a classical education. She took her learning very seriously and it soon became apparent as she grew into a young woman that she would not be satisfied with the passive role in society that had been assigned her.

Her family thought otherwise and complained that Florence, though slender and graceful deterred admirers with her earnest countenance but then she was not a young woman seduced by flattery, was rarely known to smile and did little to encourage potential admirers, though it was said that she was not at all displeasing to the eye.

Despite her objections Florence yielded to the requirement that she be both ornamental and available to suitors the most persistent of whom was Richard Monckton, the 1st Baron Houghton. He would indeed be a good catch and Florence’s mother was particularly keen that she should secure her future as soon as possible but though Florence courted Monckton to placate her family she never had any real intention of marrying him. Rather she believed that she’d received a calling from God to do good work and as early as 1837 had expressed her desire to become a nurse.

Any mention of it however provoked furious rows with her mother Frances and her sister, Parthenope; they both believed that it was not decent for someone of her status to enter the professions and that by doing so she would bring shame upon the family. Instead, she should marry well while her value as a mother was still viable. Florence remained adamant however and her relations with both her mother and sister her were strained to breaking point. It was for that reason that she kept her counsel for the next seven years. In 1844 however, she finally announced her decision to become a nurse.

Her mother was so distressed by the news that she had a nervous breakdown. Her condition wasn’t improved any when Florence also broke off her long courtship to Richard Monckton.

The willingness of her mother and sister to be subordinate to men and to gladly fulfil their expectations of what a woman should be infuriated Florence and provided her with an often-expressed contempt for both her sex and her class.

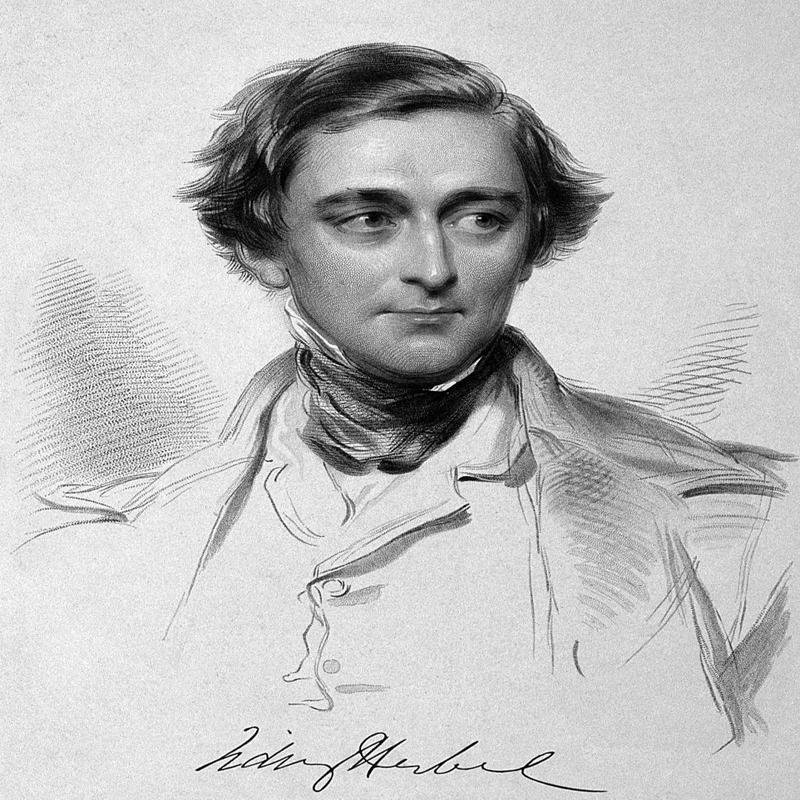

Before Florence embarked upon her career as a nurse she took what was almost a rite of passage for the well-heeled the Grand Tour of Europe and it was whilst she was resident in Rome that was to meet and become friends with the politician Sidney Herbert who was to prove pivotal in future events for it was he as Secretary of War during the crisis in the Crimea that he was to facilitate her nursing activities during the conflict.

Florence was to spend five years abroad travelling as far as Greece and onto Egypt. There she imbibed the beauty of the landscape, learned to appreciate different cultures, and saw God in all things. Her religious views were always to be somewhat unorthodox but then they had been found rather than taught, a result no doubt of her Unitarian upbringing.

Upon returning to England, she was eager to begin her calling.

On 22 August 1853 she took the post of Superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlemen in London and her talent for administration quickly became apparent. She also established her school for the training of professional nurses at St Thomas’s Hospital and began to turn what had previously only been thought of as a by-product of a woman’s nature and a reflection of their nurturing spirit into a vocation and a career.

Florence’s determination to succeed and refusal to be spoken down to by either men or women saw her reputation grow alongside her achievements.

The dispute that was to lead to the Crimean conflict began over Russia’s attempt to exploit the weakness of the crumbling Ottoman Empire, the so-called “Sick Man of Europe,” by seizing her territories in the Balkans. The Western powers, most notably Britain and France feared that if Russia did so she would also seize Constantinople and thereby gain access to the Mediterranean for her powerful Black Sea Fleet. In response, and to sustain the Ottoman Empire as a buffer to Russian territorial ambitions in July 1853, British and French forces landed on the Crimean Peninsula. It was however a hastily prepared, ill-organised, and poorly equipped campaign that had not considered, the conditions they would encounter, neither the extremes of climate and weather, nor the propensity of disease. It was not long before thousands of men were dying, not from wounds sustained in battle but from sickness alone.

The horror of the campaign in the Crimea and the incompetence of those running it were highlighted by regular dispatches sent from the front-line by the world’s first effective War Correspondent, William Howard Russell and printed in The Times. Like most people who read these reports Florence Nightingale was not just appalled by what was occurring in the Crimea but equally disgusted that nothing appeared to be happening to alleviate the situation.

She considered petitioning her old friend the Secretary of War Sidney Herbert for permission to travel to the Crimea with a number of her trained nurses but as it transpired, she did not have to, Webb was well aware of her work at her Institute in London and of her vocation and was under pressure to organise a mission to go out to the Crimea to sort things out.

In September 1854, he wrote to her: “There is but one person in England that I know of, who would be capable of organising and superintending such a scheme”.

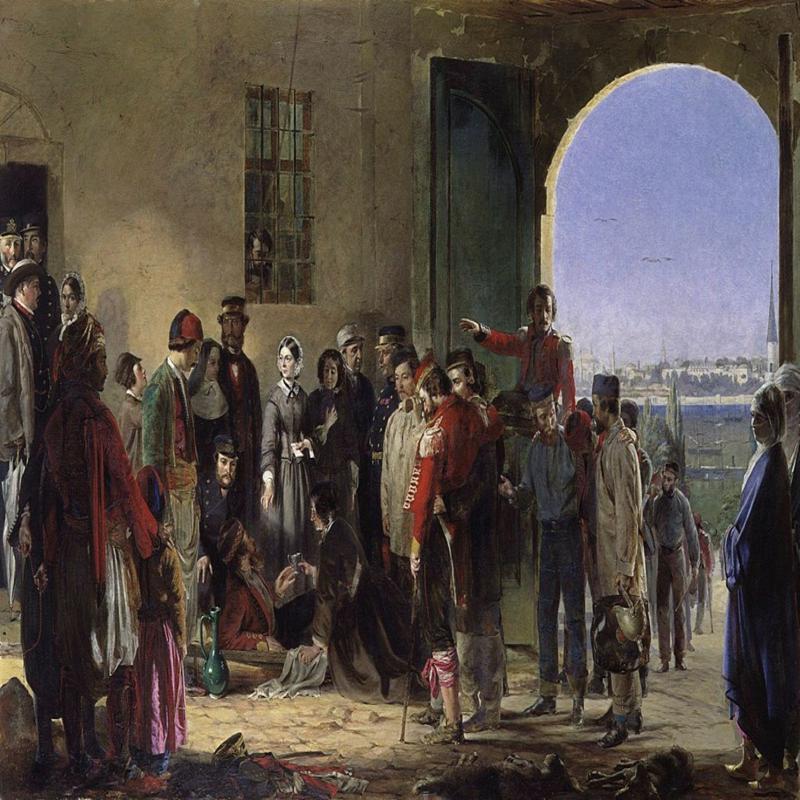

Florence did not hesitate and left for the Crimea in late October with 38 trained nurses.

The main British Field Hospital was at Scutari on the Turkish mainland some 250 miles distant from the front-line on the other side of the Black Sea. When Florence arrived at the Selimiye Barracks she was shocked at what she found. She wrote of her horror: “We have four miles of beds not eighteen inches apart, we are steeped in blood”.

The place was rat-infested, and any semblance of hygiene was non-existent. Many of the sick and wounded soldiers who arrived there were already close to death and infection was so commonplace that it was viewed more as a mortuary and a final resting place than a hospital.

Hands were not washed, and neither were wounds, bandages and bedding remained unchanged, filthy clothes remained unlaundered and surgical instruments were not cleaned. The walls and floors of the hospital had not been washed, most of the windows were missing, and there was a shortage of beds and blankets with soldiers forced to lie on the ground in nothing but their tattered and threadbare uniforms. Indeed, there was a shortage of almost everything and many soldiers were dying of scurvy and other easily preventable diseases. The more deadly typhus, cholera, and dysentery were also rife and not helped by sick soldiers too weak to move being left to carry out their bodily functions where they lay.

Florence Nightingale was not at all daunted by the task that now faced her but instead set about her work with vigour and determination.

Though she did not perceive hygiene as the problem in any scientific sense she adopted a common-sense approach that said if something was dirty you cleaned it. Her primary task she thought was to see that there were adequate medical supplies and that they were administered regularly. She also worked alongside the Sanitary Commission to clean up the sewers, dispose of the rats and improve ventilation. But she also brought the social prejudices of her day with her.

She was greatly concerned by what she saw as the flirtatious behaviour of some of the younger nurses and she preferred to employ older women, and she banned her nurses from visiting the wards after 8.30 at night. Also, certain male body parts could only be cleaned by male orderlies and she opposed any of her nurses visiting and working on the front-line, though she later relented on this.

Though she regularly did her nightly rounds Florence was primarily an administrator rather than a nurse, but she nevertheless became famous during the Crimean War as “The Lady with the Lamp,” a phrase first coined to describe her in The Illustrated London News:

“She is a ‘ministering angel’ without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow’s face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical officers have retired for the night and silence darkens down upon those miles of prostrate sick, she may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hands, making her solitary rounds.”

Despite her administrative skills, hard work, genteel manner, and regular attendance in the wards she remained a distant presence to the soldiers, someone to be smiled at but not spoken to. Her spreading fame however meant that when on 29 November 1855 the Nightingale Fund for the training of nurses was launched the donations flooded in.

Mary Seacole was born Mary Grant in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1805.

She was the daughter of a black woman and a white Scottish soldier; her mother had been a respected herbal healer and Mary who had learned her skills as a child was to follow in her footsteps. Although, she always emphasised her Britishness and took great pride in her Scottish ancestry was never dismissive of her black antecedents writing in her autobiography:

“I have a few shades of deeper brown upon my skin which show me related – and I am proud of the relationship – to those poor mortals who you once held enslaved, and whose bodies America still owns.”

Despite her evident pride she was to remain scornful of being described as either black or coloured preferring the term Creole.

On her first visit to London in 1821 she encountered little if any racism. The city had long had a thriving black community and it was said that she was of a lighter sort with a mere dusting of colour though of Negro features and she drew little attention.

Returning to Jamaica in October 1836 she married Edwin Seacole whose middle names were Horatio Hamilton leading some to speculate that he was the illegitimate child of the late Horatio Nelson and his lover Emma Hamilton. Certainly, Mary liked to think so but there is little real evidence for it. For a time, they ran a boarding house together in Kingston until it burned down in 1843. The following year Edwin died.

Mary later wrote of her shock and dismay at the tragic turn of events and how for a time she was at a loss what to do but she soon turned to the skills she had learned from her mother to make ends meet and was soon in demand as a practitioner of herbal medicine. Her reputation was further enhanced by her kindness in treating the victims of the cholera epidemic of 1850 that was to claim so many lives.

Soon after Mary travelled to Panama to treat those building the Canal who were suffering from typhoid fever and later onto America and it was here that she was to encounter unsubtle racism for the first time. It both shocked and appalled her.

Mary was back in Panama when she learned of the outbreak of the Crimean War and thrilled by the prospect of experiencing conflict and determined to help those from what she considered her spiritual home she set sail for England.

She travelled to England with letters of recommendation pertaining to her medical skills and once settled in London applied to the Medical Department and the War Office to serve as a nurse in the Crimea but did not receive a reply from either.

Her letters of recommendation from doctors in the Caribbean carried little weight in London, and so she wrote to Florence Nightingale in person offering her services but again received no reply.

She wasn’t the only black woman whose offer of help in a nursing capacity was rejected and it wasn’t just because of any racial prejudice or discrimination on the part of the Authorities for it was also a widely held view that the British soldier would object and refuse to be treated by a woman of colour, even if someone in pain rarely rejects the help of those who can relieve their distress.

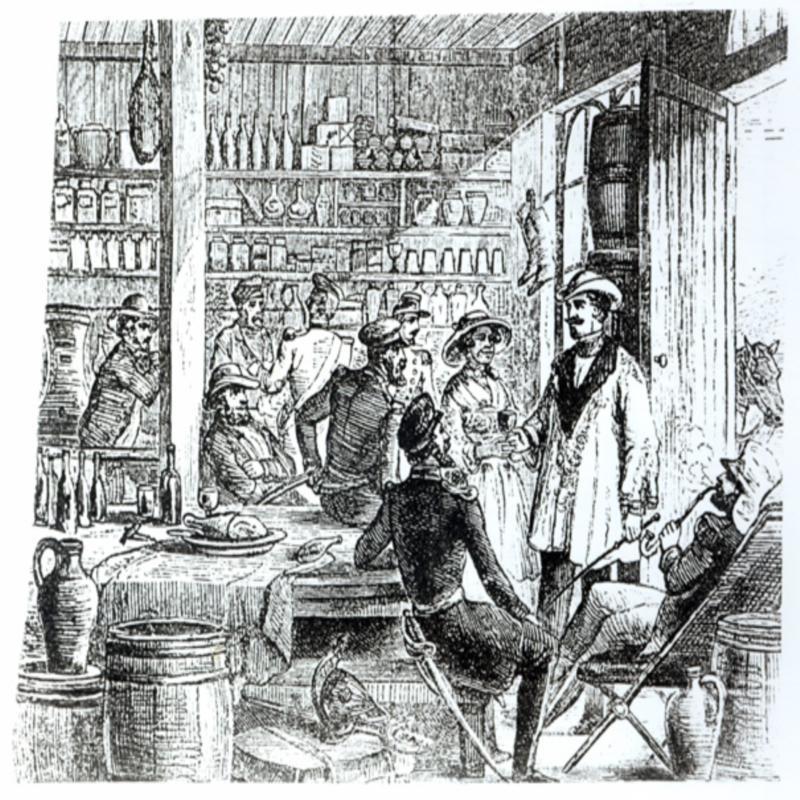

Regardless of the rejection, Mary remained determined to go to the Crimea and find a partner who was willing to fund her journey, but she was not just going to tend to the sick she was going into business. She intended to establish the British Hotel for sick, wounded, and convalescing Officers. She had business cards printed and letters were sent ahead advertising her imminent arrival.

Mary arrived at Scutari in March 1855 with a letter of introduction on her person for Florence Nightingale.

She was to describe their meeting and subsequent meetings as being friendly and cordial, but they were two very different women. The avuncular and gregarious Mary did not strike the prim and proper Florence as being suitable material for a nurse. Neither did they see eye-to-eye on what a wounded or sick soldier required from one.

Although Florence thanked Mary for her interest and provided her with a bed for the night her services were once more declined. So, Mary made her own way to the Crimean Peninsular the following day and her British Hotel opened for business soon after.

Though she provided herbal medicines and helped bandage wounds her hotel was not a hospital but a run for profit store that provided a place to relax, to drink coffee and where she made alcohol readily available.

Unlike Florence Nightingale who rarely left Scutari believing that her best work could be done away from the arena of conflict, Mary Seacole was often to be seen in the aftermath of a battle tending to the wounded and cradling the dying.

She also did not share Florence Nightingale’s inhibitions and would visit the various encampments with her wagon full of herbal remedies and medicinal alcohol and was willing to administer her cures whatever the sickness may be or wherever on the body the wound may have occurred. She also instinctively understood the psychology of the fighting man and regardless of the situation there was never a reason for a man not to be happy. After all things could always be worse and she was always positive, rarely seen without a smile and never short of an encouraging word.

Ever generous with her time she was likewise with her goods despite the profit motive that was the basis of her business partnership and the reason for her being in the Crimea. She did not let profit impinge upon her caring nature something the soldiers appreciated and whereas they respected Florence Nightingale they regularly referred to Mary Seacole as “Mother Mary” or “Mother Seacole.”

Florence Nightingale was aware of Mary’s work in the Crimea and her attitude towards her was ambivalent at best and sometimes openly critical. She wrote of her so-called British Hotel: “I will not call it a bad house (Victorian code for a brothel) but something not very unlike it.” She also wrote: “She was very kind to the men and what is more to the Officers, and did some good but she also made, many drunk.”

There was a strong element of social snobbery in Florence’s attitude to Mary and no doubt a degree of racism but there was also a strong element of jealousy for she could behave in a way towards and relate to the soldiers in a manner that the social conventions of the time did not allow Florence to do.

The losses incurred on all sides during the Crimean War were simply staggering and in just two and a half years of conflict on that tiny peninsular it is estimated that as many as 500,000 men may have lost their lives.

The British lost 22,000 men of whom 6,000 died in battle the rest succumbed to disease and infection from untreated wounds. Such percentages were reflected in the other armies also but the presence of Florence Nightingale at Scutari and the work of Mary Seacole and other nurses on the front-line did bring the British rate of loss down, but it would take time.

Their unstinting work was to make them heroes in a war most notable for its administrative chaos and military incompetence.

A series of bad investments by her business partner saw the profits from her British Hotel quickly squandered and Mary Seacole returned to England from the Crimea poorer than when she had left. She was however at the height of her fame and was awarded the Crimea Medal and the French Legion d’honneur, and such was her popularity that there were many fund-raising events organised on her behalf.

A Testimonial Fund was established to which many prominent Victorians made donations including Florence Nightingale. In July 1857, her autobiography was published the foreword for which was written by William Howard Russell: “I have witnessed her devotion and courage, and I trust that England will never forget one who has nursed her sick.”

Mary Seacole ‘s determination to tend to the wounded regardless of her own safety won her the undying affection of the soldiers she treated but her contribution to healthcare was minimal with many of her herbal remedies dismissed by doctors as little better than Voodoo medicine. Likewise, her legacy is difficult to define and one of psychological impact and abiding memory rather than any significant contribution to nursing or the medical profession. Her willingness to face danger simply to pass a kind word to a dying man is to be admired but she never formally fulfilled the role of a nurse and was in the Crimea first and foremost as a businesswoman.

Mary Seacole, whose courage was widely acknowledged at the time, died in Paddington, London, on 14 May 1881 aged 76, having been able to live out her last years in some comfort due to the generosity of those who still cherished her memory.

Florence Nightingale returned to Britain an icon of Victorian womanhood, but she was never distracted by her new-found fame and continued to dedicate herself to her profession. She not only continued to establish schools for the training of professional nurses, but she also pioneered the use of statistics and the pie chart to determine degrees of success and failure, worked closely with the Sanitary Commission to improve hygiene, was a pioneer of preventative medicine, and saw that trained nurses were employed in the Workhouse.

Though she has been criticised in recent years for not being an advocate of germ theory, she was more of a miasmalist believing that dirt and filth poisoned the air rather than germs being the root cause of an infection, there is little doubt that she saw the lack of hygiene as a problem and resolved it.

Florence Nightingale never fulfilled her parent’s wishes remaining a spinster for the rest of her life during much of which she was ill often taking to her bed or needing to be carried from place to place. Whether her malady was genuine or psychological is unknown, but it was never severe enough to keep her from her work and over the next 55 years she was to found the concept of modern nursing as we understand it today.

In 1890 she became one of the first people to have her voice preserved for posterity on phonograph when she recorded these words in support of the Charge of the Light Brigade Relief Fund:

“When I am no longer even a memory, just a name, I hope my voice may perpetuate the great work of my life. God bless, my dear old comrades of Balaclava and bring them safe to shore”.

Florence Nightingale died on 13 August 1910 at her Mayfair home aged 90.

She had earlier declined the offer of a state funeral and burial in Westminster Abbey for a private ceremony and a grave in the family plot at St Margaret’s Church in East Wellow, Hampshire.

Share this post: