French Revolutionary Calendar

Posted on 12th January 2021

Revolutions are rarely as they first appear but merely the (often) violent overthrow of one regime and its replacement by another with the hopes and aspirations of those who took to the streets, waved the flags, carried the placards, and chanted the slogans speedily trampled underfoot by a new authority no less brutal in its determination to eliminate that which is contrary to the interests of those they now represent than had been the regime it replaced.

But what is a revolution if it is not the spinning of the wheel and in late eighteenth century France it turned again and again from moderation to co-operation, to intolerance, intransigence, and finally terror.

But if the essential nature of power remains the same then at least the trappings that adorn and lend it legitimacy can be changed, utterly if necessary, and what could be more transformative than the alteration of time itself, that, and the people’s perception and understanding of it.

The new calendar for the new age, like the new religion and the new morality, was designed to sweep away all vestiges of the Ancient Regime and is most closely associated with the mathematician and agronomist Gilbert Romme, who headed the Commission established to create it; and it was he and the flamboyant, grandly named Philippe Francois Nazaire Fabre d’Eglantine, failed playwright and recent convert to revolution who, along with the assistance of the ex-Royal gardener, would provide the months of the year with their new titles.

The creation of the new calendar, though it was dismissed by some as an irrelevance at a time of war and counter-revolution, was taken seriously and engaged many of the finest minds of the time including the astronomer Joseph-Louis Lagrange, the geographer Alexander Pingre, and the chemist Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau among others.

These men of science and philosophy dug deep into ancient history, studied the motion of the planets, and worked hard at the arithmetic whilst remaining within the framework of the Enlightenment and paying due respect to the legacy of the Roman Republic they so admired. Their conclusion - time was to be decimalised: A minute would now be 86.4 seconds, there were to be one hundred minutes to the hour, ten hours to the day, and thirty days to the month divided into three ten-day weeks. There would still be twelve months to a year which now began the day the Autumnal Equinox occurred in Paris - the Revolution was always about Paris.

Any adjustments required, such as in a leap year or to maintain regulatory uniformity would be made with reference to this decimal equation. Where the adjustment could not be made the day would simply disappear.

The names of the month were to be changed and would reflect the prevailing climate and what this meant for the agricultural cycle. Likewise, each day had a title. For example: 12 Vendemaire was Immortelle, or Strawflower; 15 Pluviose, Vache, or Cow; 11 Prairial, Fraise, or Strawberry; 19 Messidor, Cerisse, or Cherry. And the days of the week were numbered in Latin from 1-Primordi to 10-Decadi.

However, unlike industry farming is not subject to the tyranny of the clock but is dictated to by the sun when it rises and when it sets. Changing time, even any notional understanding of it, means little to the horny-handed son of the soil. Regardless, the new Calendar was presented to the Jacobin controlled National Convention by Gilbert Romme on 23 September 1793, and formally accepted the following month.

It had originally been intended for it to commemorate the fall of the Bastille and the Revolution of July 1789, but it was decided that to do so would be to acknowledge the previous regime and the fact that for three years the revolution had sought an accommodation with it. So instead, it was backdated to begin in September of 1792, following the fall of the Monarchy and the establishment of the Republic - the Revolutionary Calendar then, had become the Republican Calendar.

Fabre d’ Eglantine was to promote the calendars virtues to both the Revolutionary Tribunal and the Committee of Public Safety. France now had a new framework to live by he told them, hour-by-hour, day-by-day, month-by-month Perhaps, but the calendars widely distributed were largely ignored and the clocks manufactured to reflect the new time remained unsold.

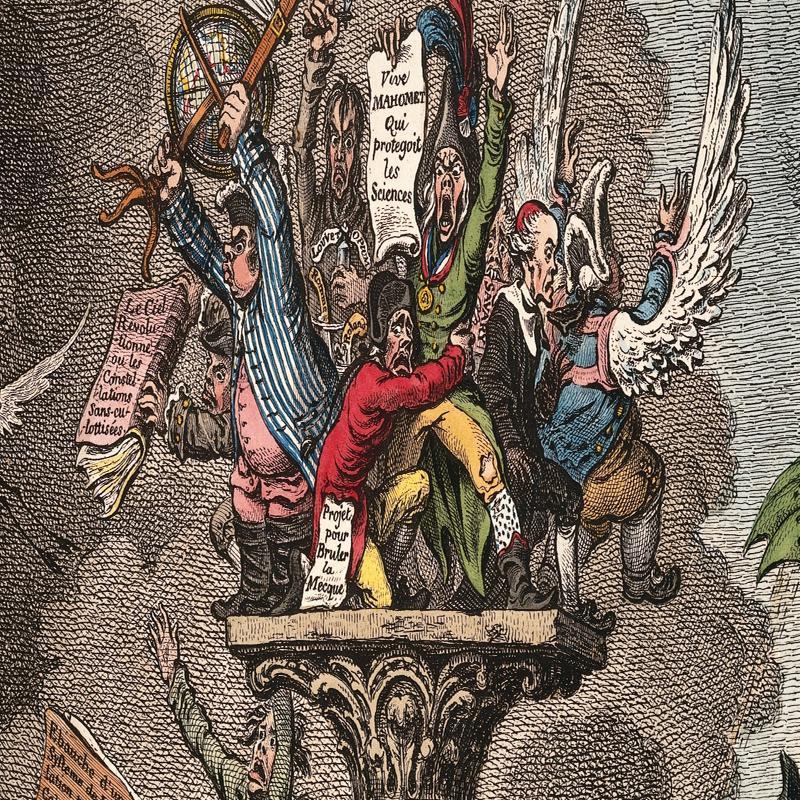

The British, who were then at war with France and would be except for a short break for the next fifteen years, found the Calendar a useful propaganda tool poking fun at the utopian fantasies of the revolution satirising the months as - Wheezy, Sneezy, Freezy, Slippy, Drippy, Nippy, Showery, Flowery, Bowery, Happy, Croppy, and Poppy. And that no number of cheery names and pictures of pretty girls could disguise the hatred, division, and bloodshed that was Revolutionary France.

The French Revolution is often said to have ended with Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup of 18 Brumaire, or 19 November 1799, but it wasn’t until 1 January 1806, almost two years after he had crowned himself Emperor, that he formally abolished the Republican Calendar.

Long before the Calendar they had created fell victim to a coup its two main protagonists had fallen victim to the Revolution they had so enthusiastically embraced.

On 5 April 1794, or 16 Germinal of the Year II, Fabre d’Eglantine was executed on the orders of the Committee of Public Safety for the crime of corruption and malfeasance. Having tried to blame everyone else for his predicament he was to bitterly complain of the injustice of it all so much so that on his way to the scaffold Danton who was also to be executed suggested that he cease carping about it and accept his fate.

On 17 June 1795, or 29 Prairial of the Year III, Gilbert Romme committed suicide on the steps of the Courthouse where he had just been sentenced to death by stabbing himself repeatedly with a small knife he had concealed on his person.

Both men had died in the shadow of that other great symbol of the French Revolution the Guillotine.

The months of the Revolutionary Calendar were as follows (each month was accompanied by the image of an attractive peasant girl picking flowers, caring for animals or something similar):

Vendemaire (Month of Grapes) 22 September - 21 October

Brumaire (Month of Mist) 22 October - 20 November

Frimaire (Month of Frost) 21 November -20 December

Nivose (Month of Snows) 21 December - 19 January

Pluviose (Month of Rains) 20 January - 18 February

Ventose (Month of Rains) 19 February -20 March

Germinal (Month of Germination) 21 March - 19 April

Floreal (Month of Flowers) 20 April - 19 May

Prairial (Month of Meadows) 20 April - 19 May

Messidor (Month of Harvest) 19 June - 18 July

Thermidor (Month of Heat) 19 July - 17 August

Fructidor (Month of Fruit) 18 August - 16 September

Share this post: