Gavrilo Princip: The Consumptive Assassin

Posted on 28th January 2021

On 28 July 1914, an obscure sickly student fired his loaded pistol into the open car carrying the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his wife. They were both killed and just over a month later Europe would be engaged in a conflict the like of which had never been seen before. It would leave the continent devastated - how could one man be the cause of such carnage? Certainly, he could not have explained it, and neither would he be blamed for it.

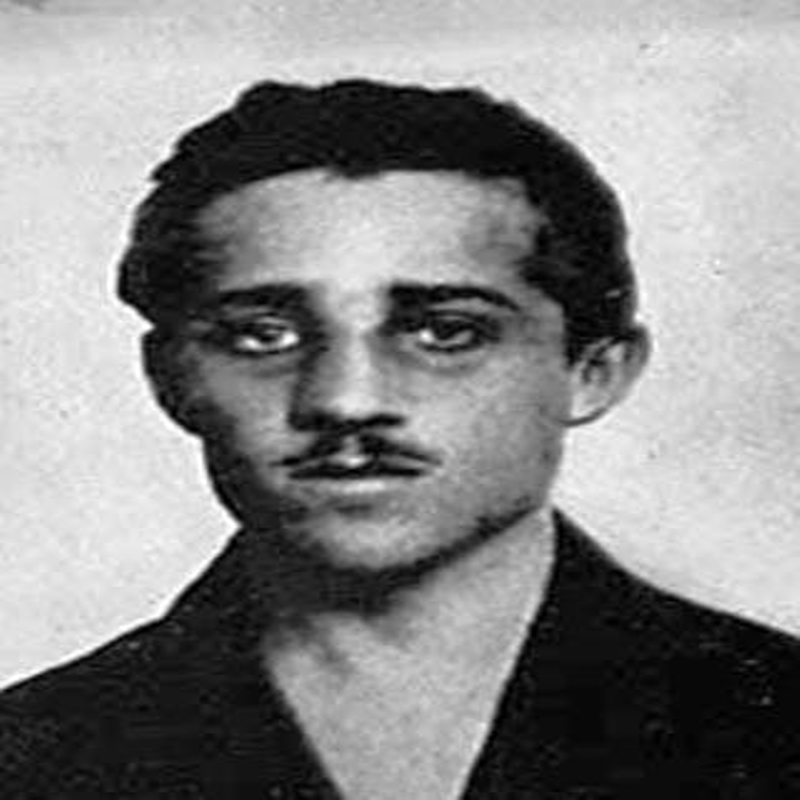

The man who sparked the events that would lead to catastrophe was Gavrilo Princip, a deathly pale and emaciated student who had become devoted to the cause of Slav nationalism.

Born in 1894, he was the son of a postman, and a child so weak he was rarely fit enough to play with other children and so remained a shy loner who merely dreamed of doing great things. After attending school in Sarajevo where he did poorly, he moved to Belgrade where he fared even worse, failing his college entrance exams. He remained unperturbed however and doubting he had long to live remained in a hurry to make his mark.

When in October 1912, a territorial dispute between Serbia, her allies, and the Ottoman Empire descended into war he immediately volunteered to serve in the Serbian Army, but despite special pleading on his part stating repeatedly that he wished to give his life in the service of his country he was turned down for being too young, a consumptive, and physically incapable of wartime service. But there were other ways of serving the cause of Slav nationalism, and he needed little persuading to join the 'Black Hand.'

Formed in May 1911, by Officers within the Serbian Army the 'Black Hand' was a Secret Society dedicated to uniting all South Slavs into a Greater Serbia. Led by Dragutin Dimitrejevic, also known as Apis, who had played a prominent role in the palace coup which had resulted in the murder of King Alexander and Queen Draga a decade earlier, the 'Black Hand' were determined to resist the spread of Austro-Hungarian influence in the Balkans by any means necessary, including assassination and even war.

The province of Bosnia-Herzegovina had been under effective Austro-Hungarian control since the Congress of Berlin in 1878, but Russian opposition had delayed its formal annexation until 1908. Many in Serbia believed Bosnia-Herzegovina should be part of the greater Slav nation but the Government was unable to oppose the annexation, and certainly not without Russian support which was not forthcoming - the 'Black Hand' thought otherwise.

When the news filtered through that the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was due to visit the Bosnian capital Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 as part of army manoeuvres, there was great excitement within the ranks of the 'Black Hand.' Here was an opportunity to strike a blow for Slav independence that may not again present itself for many years.

The Archduke's visit also coincided with the anniversary of the 1389 Battle of Kosovo when a Serbian Army had been defeated by the forces of the Ottoman Empire, a date commemorated in Serbia with great solemnity as a courageous act of Slav defiance. It seemed to some like a deliberate provocation.

Plans were laid to assassinate the Archduke and Gavrilo Princip, who in the preceding months had proved his devotion to the cause of Serb nationalism, was one of the three men selected by Dimitrejevic to travel to Sarajevo and perform the deed. The others, less well known to history, were Nedjelko Cabrinovic and Trifko Grabez.

The Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pasic, upon being made aware of the mission and fearing the consequences for his country should it succeed ordered their arrest but Dimitrejevic, in his role with Serbian Military Intelligence, did not pass the order on and now fearing that his own complicity would be discovered issued the three conspirators with phials of cyanide to be taken if captured - the assassination squad had now become a suicide squad.

The Archduke Franz Ferdinand had become heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary in 1889, when his cousin, the Emperor's son Crown Prince Rudolf had killed himself at the Mayerling Hunting Lodge in a suicide pact with his mistress, Mary Vetsera.

In contrast to the popular but unstable Rudolf, Franz Ferdinand was a distant and ill-tempered man who could be both coarse in his language and brutal in his behaviour. He was neither liked by those who served him or the people he was destined to rule. He was though, a man who took his responsibilities seriously and did not suffer fools gladly; quick to criticise in public and remove those he thought incompetent, or indeed dared to disagree with him, he had within Government circles and those at the Imperial Court. But there was also a softer, gentler side - he was a devoted family man who was deeply in love with his wife, Sophie.

It had not been until 1899, that the Emperor Franz Joseph had at last relented and agreed to his nephew marrying his long-time lover Sophie Chotek, Countess of Hohenberg, a Lady-in-Waiting to the Empress Elisabeth. It was expected for an heir to the throne of the Habsburg Empire to marry a member of one of the other ruling dynasties of Europe, and it was widely held that Franz Ferdinand had brought shame upon the Imperial Family by marrying beneath himself and had only been permitted to do so on the proviso that certain conditions were met: Sophie could not ride in the Royal Carriage, be seen in the Royal Box, or attend official ceremonies in the presence of her husband, but more significantly it would be a morganatic marriage and any children that might result from their union would not be in line to the throne. The conditions were a bitter pill for Franz Ferdinand to swallow and he did so for the sake of love, but it left him an angry man.

The visit of Franz Ferdinand to Bosnia-Herzegovina was intended to show the nations of Europe, and in particular Serbia, who controlled the region. For the Archduke it was an opportunity to cement his relationship with the army and to get away from the stifling atmosphere of the Imperial Court in Vienna, and in particular the fractious relationship he had with his uncle. He was also delighted that Sophie would be able to accompany him - they could at last be seen together as husband and wife and it would also serve as a clear statement that she as an Empress in the making.

The Imperial couple arrived at Sarajevo Railway Station early on the morning of 28 June 1914 having spent the day before visiting the city incognito to do a little shopping and sightseeing. Both were happy and smiling, Sophie was pregnant again and they were clearly enjoying the opportunity to be seen together in public.

They were greeted upon their arrival by the regional military commander Oskar Piotorek, who had invited the Royal couple to visit in the hope that it would lend legitimacy not only to the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina but his own authority. Franz Ferdinand, deeply conservative in his politics and absolutist by nature, agreed. It was a chance for him to increase his influence over the army and assert his position on the political stage.

The crowds lined the streets of Sarajevo to greet their illustrious visitor and among them were Princip and his comrades, who had since been joined by four others, who were placed strategically along the route of the Archduke's procession.

The journey was a long and torturous one as the crowds thronged around the Archduke's car and crowd control was proving difficult with the many police present only seeming to add to the chaos. The first opportunity to assassinate the Archduke fell to Mohamed Mehmedbasic, a Bosnian Muslim, but as the Archduke's car brushed past him, he was too frightened to throw his grenade. A loss of nerve he later denied. As the cavalcade neared its destination, Sarajevo City Hall, it slowed nearly to a halt. This presented Nedjelko Cabrinovic with his chance, and unlike Mehmedbasic before him he did throw his grenade but had forgotten it had a ten second fuse and as it bounced off the bodywork of the Archduke's car it rolled beneath the one following and detonated causing serious injury to its occupants.

The Archduke's car sped off and Cabrinovic fled the scene with the police in hot pursuit; fearing capture he bit into his cyanide pill, but it failed to work. In an attempt to drown himself he jumped from a bridge into the Miljacka River only to discover it was a mere four inches deep. Barely wet he was dragged out and placed under arrest, forlorn, somewhat embarrassed. In the meantime, Archduke Ferdinand appeared unperturbed by what had occurred remarking:

"That fellow is clearly insane let us proceed with our programme."

But he was nonetheless furious at the reception he'd received and now gave full vent to his notorious temper, during an address given in his honour he thundered: "What is the good of your speeches? I come to Sarajevo on a visit, and I get bombs thrown at me. It is outrageous!"

Following the dinner, he insisted on visiting those in hospital who had been injured in the earlier attack. General Piotorek, who would be travelling in the same car agreed but suggested they take an alternative route that avoided the city centre. He neglected to tell the driver however, and unaware of the new arrangements he set off as before. Realising this Piotorek began remonstrating with him.

Having driven into the logjam that was the ironically named Franz Joseph Street the driver now decided to turn the car around and take the other route as ordered. As he did so it stalled. Gavrilo Princip, believing that the assassination attempt had failed was eating a sandwich in a cafe nearby when glancing out of the window he could see the Archduke's car. It was static and stuck in a traffic jam just a few yards away from where he was sitting. He could not believe his luck. Leaving the cafe, he walked unimpeded to within five feet of the Archduke's car where he took out his Browning automatic pistol and fired seven times. His earlier target practice in a nearby park had not improved his aim any, but a bullet did hit the Archduke in the neck while another penetrated his wife's abdomen, even though he had been aiming at Piotorek. The Archduchess Sophie was heard to scream "Heavens! What's happening! What's happened to you?" She then slumped to her knees. The Archduke then shouted "Sopherl! Sopherl! Don't die, remain alive for the children."

A bodyguard travelling on the frame of the car asked, "What's wrong?" The Archduke replied, "it's nothing, it's nothing," a phrase he kept repeating until he too slumped forward.

The Archduchess Sophie was dead, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand soon would be

Princip made no attempt to flee but instead tried to turn the gun on himself but someone from the crowd grabbed his arm before he could do so. He was then overpowered by some nearby policemen and severely beaten before being dragged away.

That night martial law was declared in largely Muslim Sarajevo, but it didn't prevent riots and considerable ant- Serb violence. In the meantime, Princip did not hesitate to confess to the assassination and did so with pride, though he denied there was any Serbian involvement and regretted the death of the Archduchess Sophie.

Eventually, eight men were to be charged with the murder of the Archduke Ferdinand and his wife.

It was said that the Archduke’s assassination was greeted by the aged Emperor Franz Joseph with equanimity if not relief. He hadn’t liked his nephew and even less his common wife who as a previous lady-in-waiting to the Empress he referred to as that ‘serving wench.’ It was also the case that reforms Franz Ferdinand had spoken of implementing once he inherited the throne had also caused some disquiet in Court and Government circles.

Under Austro-Hungarian Law the penalty for murder was death by hanging but because they could not discover Princip's precise date of birth they determined that he was still under twenty-one years of age and too young to be executed. Instead, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison, the maximum allowed. Similar to Princip, Nedjelko Cabrinovic, Trefko Grabez, Vasilo Cubrilovic, Cujelko Popovic, and Mohamed Mehmedbasic werealso deemed too young to hang and instead sentenced to long terms of imprisonment. Three fellow conspirators, Velkjo Cubrilovic, Misko Jovanovic, and Danilo Ilic were sentenced to death and hanged, however.They died martyrs to the cause of Slav nationalism, at least in the eyes of some.

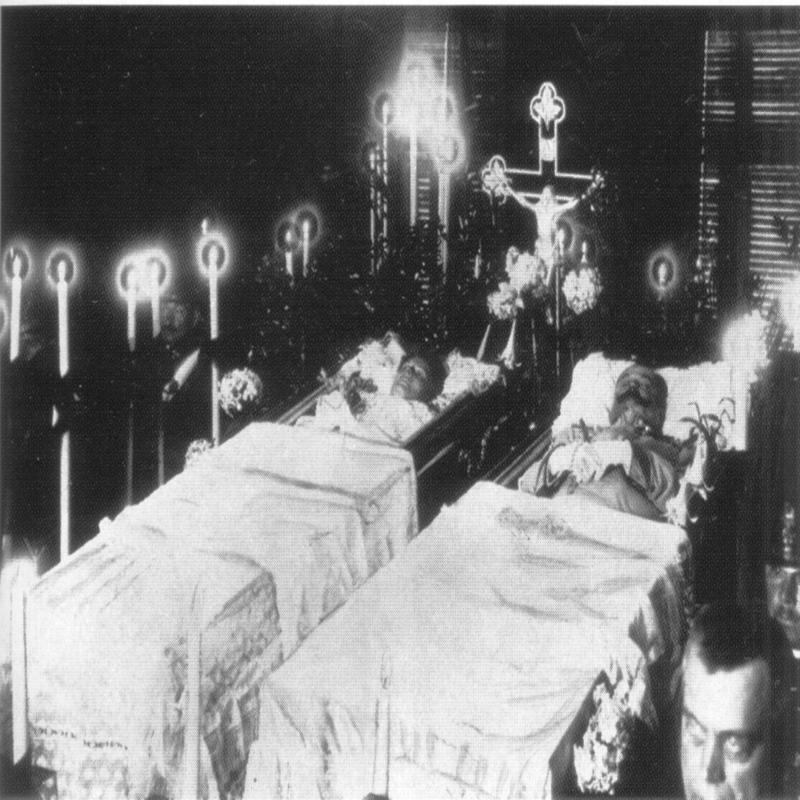

On 2 July, the bodies of the murdered Archduke and his wife were returned to Vienna and driven slowly and in silence through its streets on carriages draped in black but though the procession was suitably solemn the response to it was no less subdued. The people turned out to watch rather than to mourn their lost heir while the Imperial Family did not turn out at all. Few soldiers lined the route, and in private at least the Emperor expressed not grief but relief.

The following day a private ceremony took place before two open caskets, the Archduke's of gold that of the Archduchess silver and placed twenty inches lower than his in acknowledgment of her inferior status. The Imperial Family remained barely 15 minutes before the bodies were taken to be buried in the grounds of the Archduke's private residence as the Emperor had earlier forbidden the Archduchess from being buried in the Habsburg family crypt.

Meanwhile, in prison Princip remained defiant and refused to concede he had committed murder or accept blame for the conflict that would ensue because of his actions. When asked if he felt any guilt at the carnage he replied: "If I hadn't done it the Germans would have found another excuse."

But such was Princip's poor physical condition there was little prospect of him ever completing his sentence. Nonetheless, fearing attempts to free him from captivity he was constantly moved from prison to prison which only accelerated his physical deterioration. His last ever recorded statement was: "There is no need to carry me to another prison. My life is already ebbing away. I suggest you nail me to a cross and burn me alive. My flaming body will be a torch that will light my people on their path to freedom."

Little could he have imagined that his few seconds of murderous intent on that muggy, overcast summer's day in a city few had ever heard of would, paraphrase the British Foreign Secretary Lord Grey - put the lights out across Europe never to be lit again in a lifetime.

He may not have ignited Slav nationalism in the manner he had hoped for, but he had changed the world, and he had changed it forever.

He may not have ignited Slav nationalism in the manner he had hoped for but he had changed the world, and he had changed it forever.

Share this post: