General Slocum: Tragedy on the East River

Posted on 3rd June 2021

Not for the last time in its history a bright, sunny day in New York City would witness a tragedy that reaped a terrible and deadly harvest at a time when nothing could have been further from the mind of most people.

George Haas, the Pastor of St Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in the ‘Little Germany’ district of Manhattan had organised an annual Sunday-School picnic for his mostly working-class congregation. It was an event always greatly anticipated providing as it did a rare and affordable opportunity for so many to escape the often-grim circumstances of their everyday life. This year the Reverend Haas had raised $350 with which he chartered the paddle-steamer General Slocum for a cruise down the East River to Long Island and a day out at Locust Point on the Sound.

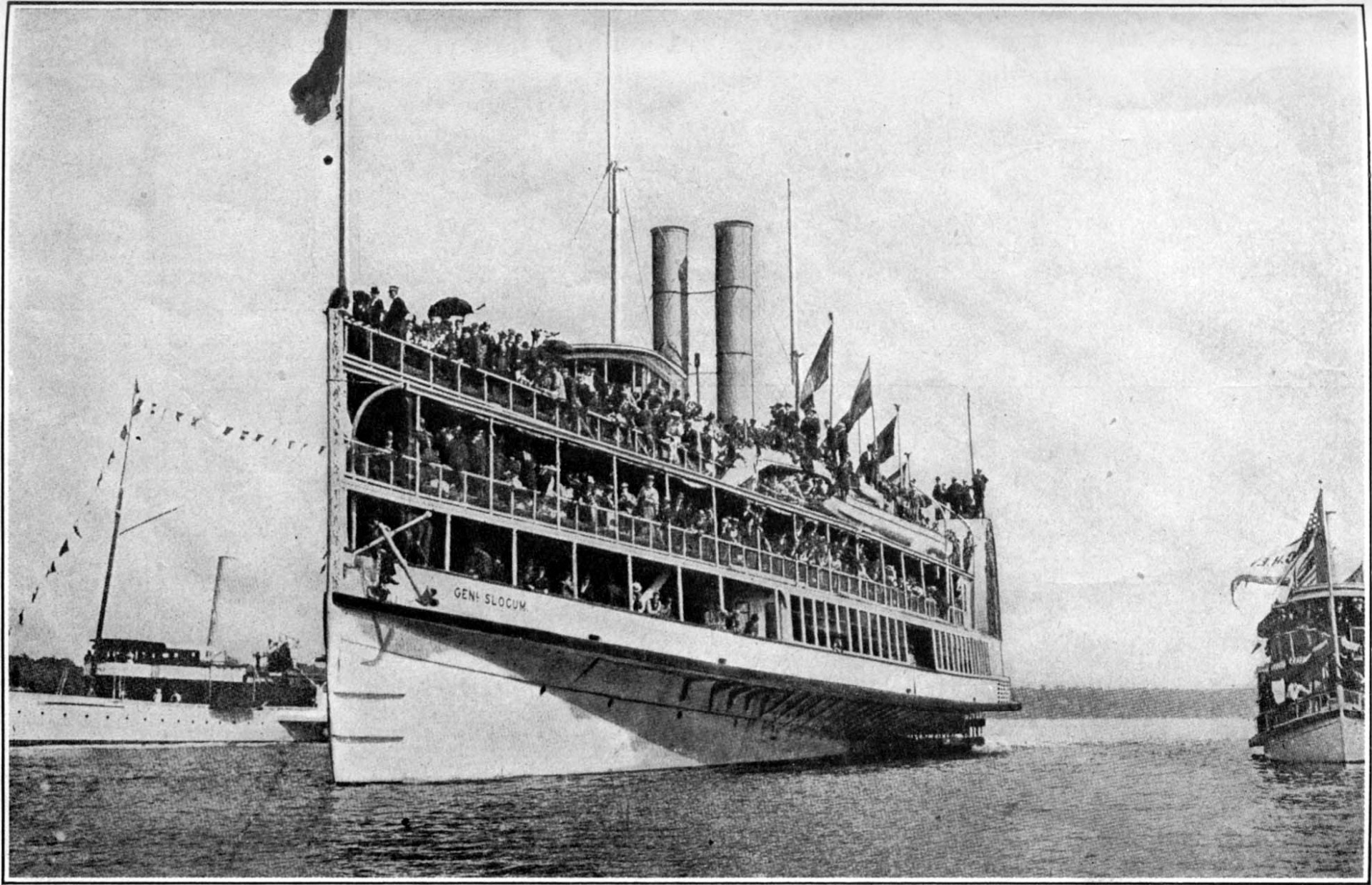

Owned by the Knickerbocker Steamship Company the General Slocum was one of many such cruise ships that plied their trade on the Hudson River and laid down only twelve years earlier it was one of the most modern and attractive of them. But its short life had been littered with mishaps including collisions, running aground and on one occasion a riot that had to be quelled by the police. Yet despite the superstitious mind of those who make a living from the water it was not thought ill-fated.

The paddle-steamer’s Captain was William Van Schaick, who at 68 years of age was a veteran close to retirement who knew the river like the back of his hand and had recently been rewarded for his dedicated service in ferrying so many people safely up and down New York’s waterways over so many years. He, along with the pilot and chief engineer were experienced mariners unlike the rest of his 22-man crew who were untrained labourers many hired on the day of sailing, but then cruising down the East River was a routine occurrence and hardly considered a hazardous endeavour.

Most of the General Slocum’s 1,358 passengers were women and children who with money saved for the occasion, dressed in their finest clothes and wearing what jewellery they had were greatly excited at what was always a special day.

With the Captain and the Reverend Haas present to greet them at 9.45 am the passengers began boarding the General Slocum which painted white and adorned with bunting and flags glistened splendidly in the early morning sun; the festive atmosphere was intoxicating as the band played traditional German folk songs and long-time friends and fellow parishioners mingled together and gossiped excitedly about recent events and the day to come.

But there was an incident when a Mrs Straub who’d earlier had a premonition of disaster fled screaming with her children from the ship moments before it was due to depart dramatically pushing aside the Pastor and Captain Van Schaick as she did so. But Mrs Straub’s antics did little to dampen the enthusiasm of anyone else.

As the General Slocum set off down the East River its three decks were crammed with people enjoying the sunshine and waving to those ashore oblivious to the danger that lurked within the belly of the ship.

In the Lamp Room, a storage space towards the front of the vessel packed with glasses, kerosene, hay and a large stove a spark had ignited, and a small fire had already been smouldering for some time. Some later suggested that in preparing chowder for the passengers the stove had been lit and then left unsupervised but as no proof can be provided for this it remains mere speculation.

At around 10.00 am, just 15 minutes into the General Slocum’s voyage a 12-year-old boy Frankie Peditsky saw smoke emerging from beneath the door of the Lamp Room but when he reported it to deckhand George Cokely, he was told in no uncertain terms to clear off and not say a word.

Cokely, who like most of the other deckhands aboard had received no training in how to deal with a fire, now made the elemental mistake of opening the door which provided what had been a small fire with the oxygen to become a blaze. He did his best to douse the flames but with no firefighting equipment available there was little he could do.

In the meantime, Frankie Peditsky had made his way to the top deck where he ran towards the bridge shouting fire – fire! Few people paid him any attention and certainly not the captain who like most others thought he was just playing a silly, if not much appreciated prank. By this time the fire had spread to the engine room where an attempt was made to put it out with the fire hose so old that the pressure of the water simply caused it to burst.

All attempts at fighting the fire were now abandoned and it was only now Captain Van Schaick informed that there was a fire at all. A vital ten minutes had been lost during which the captain had been sailing full steam ahead which had merely fanned the flames, now as he looked out from the bridge, he could see that people were fleeing the forward part of the ship and he could hear their screams as they did so. He now had little choice but to beach the ship and at the nearest available spot but as he later explained in his testimony to the subsequent Board of Inquiry:

“I started to head for One Hundred and Thirty-Fourth Street but was warned off by the Captain of a tugboat who shouted that the boat would set fire to the lumber yard and oil drums.”

But this was just one version of the many he was to tell in respect of his actions during those next few minutes.

Before he could do anything, pandemonium had broken out as over a thousand people packing just one half of the ship pushed and jostled for a place away from the flames and fought each other over life jackets as the blaze continued to advance rapidly towards them. Some tried to launch lifeboats only to find that they had been wired to their fixings and could not be budged whilst a number of survivors would later claim that many of the lifeboats had not existed at all but had merely been painted on to give the illusion that they did.

The life jackets were also to prove useless as old and shoddily made many simply disintegrated in people’s hands while those mothers who attached a life jacket to their child before lowering them into the water endured the frightful sight of them disappearing beneath the water like stones.

Similarly, those who had jumped overboard to avoid the flames at a time when few people could swim, in particular women for whom it was not thought a fit and proper thing to do, were quickly dragged beneath the swirling waters and drowned. Even those who could swim, weighed down by their full-length dresses and heavy boots, and in the case of the men thick woollen suits, could not remain afloat for long. Others got caught up in the paddle steamers still churning wheels. And as with all tragedy there were acts of heroism, cowardice and deeds of a despicable kind.

Always a busy river many boats now rushed to help while people gathered on the shoreline to watch the disaster unfold. Two New York City Policeman, Tom Cooney and Tom Skelley commandeered a tugboat and pulled alongside the blazing General Slocum dragging people, some with their clothes and hair quite literally on fire, from its deck rescuing 24 people, mostly children.

Many of those who rushed to help would themselves be severely burned and Officer Cooney would later be reported to have drowned attempting to rescue a woman from the water; but not everyone behaved with such nobility and some would-be rescuers proved to be nothing of the sort pulling women from the water only to rob them of their possessions before throwing them back in.

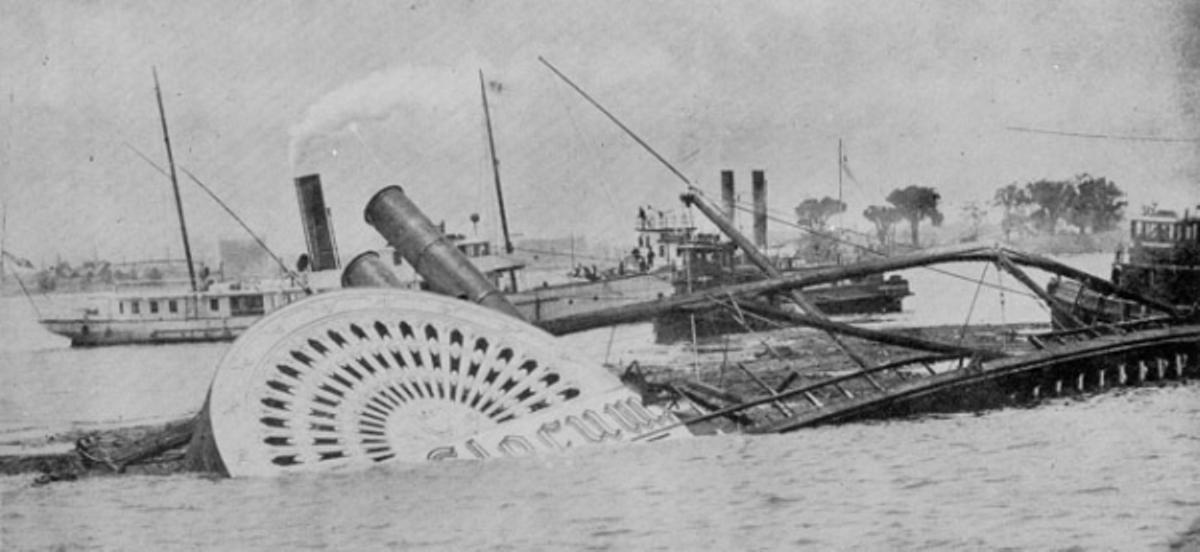

In the meantime, Captain Van Schaick steered the blazing hulk towards North Brother Island just two minutes steaming time away but by now every passing second was costing another life; reaching his destination he now inexplicably beached the burning aft section of the ship leaving its bow where the remaining passengers were huddled still in deep water.

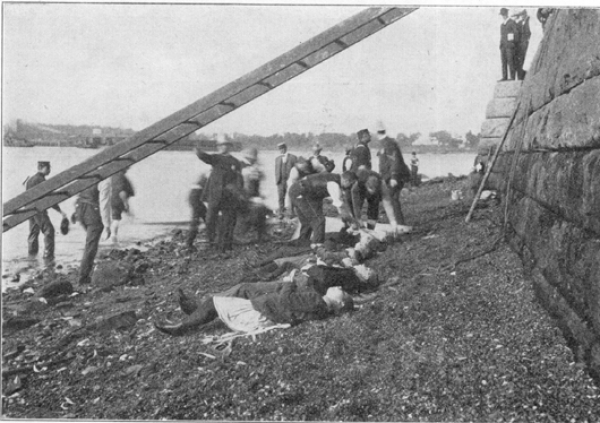

North Brother Island housed several hospitals for people suffering from contagious diseases and the staff and even some of the patients now rushed to try and help with someone having the idea to attach ropes to ladders which were then thrown into the river for people to grab hold of so they could be dragged from the water. Meanwhile, others formed human chains in the river to hold out a helping hand or try and grab bodies as they swept past.

But within minutes what had begun as a rescue operation had become one merely of salvage and recovery and of the 1,358 mostly women and children who had set off from the East Third Street Pier just thirty minutes earlier 1,021 had perished and many others had been horribly burned. Indeed, so great was the death toll that the city’s morgues could not cope with the numbers and so the bodies were laid out instead in the Alexander Avenue Station which witnessed terrible scenes as distraught relatives sought to identify their loved ones among the lines of horribly burned and mutilated corpses.

The sinking of the General Slocum had been the worst maritime disaster in the history of the United States and for weeks after bodies would be washed up on the city shoreline as it was plunged into deep mourning for the loss of so many innocents and the district of ‘Little Germany’ would never recover from its impact.

Reverend Haas survived the sinking but was in a sorry condition having lost his wife and young daughter. Captain Van Schaick also survived along with all but four of his crew in what did not appear to have been a case of women and children first.

Some reports stated that the captain appeared unruffled, others that his clothes were singed and that he was clearly in a state of great distress. Regardless, of whether he had fought to the last to save as many of his passengers as he could or abandoned his ship at the first available opportunity he would be blamed for the disaster.

In the immediate aftermath of the tragedy several Executives of the Knickerbocker Steamship Company, a Maritime Inspector who just weeks earlier had passed the General Slocum safe, the Pilot, and Captain Schaick were arrested on various charges but despite the widespread sense of horror and outrage in the end only Schaick would face prosecution for criminal negligence and manslaughter.

Although no verdict could be reached on the latter charge, he was found guilty of failing to maintain the ship’s firefighting and life-saving equipment, of not properly implementing safety procedures and not providing adequate training for his crew.

On 27 January 1906, Captain William Van Schaick having been told by the Judge that he was ‘no ordinary criminal’ and must be made an example of’ was sentenced to ten years imprisonment, the maximum penalty allowed for the crime of criminal negligence.

Surprisingly perhaps, given the circumstances, there was some sympathy for Van Schaick who many felt had been made a scapegoat for the casual indifference of his employers and the Government Inspectors who many suspected were on their payroll, and as a result his wife was able to get more than 200,000 signatures on a petition demanding his release. His appeal against the sentence was denied however, and with President Theodore Roosevelt refusing to countenance a pardon on 8 February 1908, the 70-year-old Van Schaick entered New York’s notorious Sing-Sing Prison.

Roosevelt’s successor as President, William Howard Taft felt differently about Van Schaick sharing as he did many of the concerns voiced that his imprisonment was in part the result of wanting to focus all the blame on one man and away from those who were no less culpable.

On 19 December 1912, after serving four years of his ten-year sentence Captain Van Schaick was granted a Presidential Pardon and walked from prison a free if not entirely vindicated or innocent man. He died aged 90 on 8 December 1927, after a long and mostly incident free life.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: