George and Caroline: A Royal Marriage from Hell

Posted on 21st July 2021

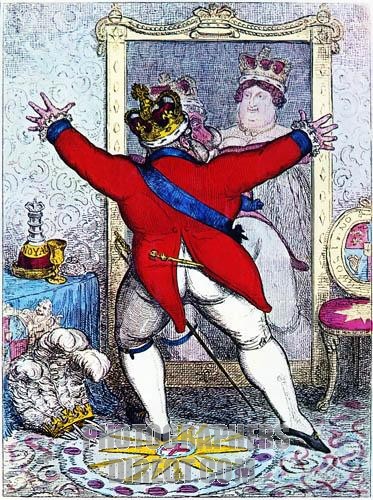

George Augustus Frederick, Prince of Wales, was heir to the throne of Great Britain but this was no guarantee of respect. Indeed, in a life mired in scandal he became the most mocked, lampooned and unpopular Monarch in our history. So different to his more down-to-earth, austere and hard-working father, King George III.

As a young man he had been noted for his intelligence and razor-sharp wit. His repartee, it was said, was something to behold whether drunk or sober. Unfortunately, by the time he was in his early twenties he was more often the former than the latter but even so he still retained his admirers, if only for his good taste and love of fine things.

He was also physically attractive though more pretty than handsome, but his dissolute lifestyle would soon take a heavy toll. He lived extravagantly and considered himself to be what we would know now as a style icon. One of his closest companions was the famous dandy, Beau Brummel.

Upon reaching the age of manhood he received an annual income from his father of £50,000 and a further £60,000 grant from Parliament. Huge amounts of money to the tune of millions today yet it was barely ever enough to enough to cover his outgoings as he commissioned the building of Brighton Pavilion, reconstructed Windsor Castle, purchased Carlton House, held lavish parties and lived in magnificent splendour. To the people he would come to rule he was a lazy, self-indulgent nitwit who squandered the nation's money.

This was not how he saw himself however, as far as he was concerned, he was the height of fashion, the finest Prince in Europe and one of the leading men of his age. It didn’t stop him being regularly jeered at and verbally abused as he rode in his carriage through the streets of London. If he was a man worthy of respect then he failed to convey these qualities to his people - he was a figure of ridicule and loathing and he struggled to understand why.

IIn 1783, he met and became besotted with Maria Fitzherbert, a twice married Roman Catholic six years his senior. They very quickly became lovers and on 15 December 1786 in a private ceremony they were married.

As the heir to the throne, he was barred from marrying a Roman Catholic by the Act of Settlement of 1701 and so the marriage was illegal He was also obliged by the Royal Marriages Act of 1772, to obtain his father's permission to wed and he was not even on speaking terms with his father.

By 1787, the Prince’s debts were such that he was forced to go cap-in-hand to Parliament but despite being bailed out on this occasion it wasn't long before he once again found himself in financial trouble. His father, despairing of his son's indolence refused to help him unless he agreed to make a royal marriage.

The Prince had only been kept solvent by the financial machinations of that master political manipulator Charles James Fox who had since told him that he could do no more. He had little choice but to agree. The woman chosen to be his bride was Caroline of Brunswick.

Caroline's mother was the Princess Augustus the sister of George III so Caroline, and the Prince were first cousins but despite this they had never met. She had been chosen because Brunswick, though only a small German principality was a useful ally in Britain’s on-going rivalry with France. George had only agreed because he needed the money.

On 20 November 1794, Lord Malmesbury arrived in Brunswick to escort the future Queen to England. He was not impressed by what he saw and noted in his diary that: she lacks judgement, decorum and tact; speaks her mind too readily, acts indiscreetly and often neglects to wash or change her dirty clothes. Her father had earlier informed him that her education had been sorely neglected.

Malmesbury's attitude toward Caroline was always ambivalent. He admired her courage and agreed that she had a natural and not an acquired morality. Even so, he did not think she was suitable to marry the Prince.

George was not one to hear home truths instead he thrived on flattery - he was the most handsome man in England, he was the best dressed man in England. This coarse, tactless, and plain speaking young German woman was unlikely to flatter his ego.

Caroline arrived in England on 5 April 1795, and was placed with Frances Villiers, Countess of Jersey who had been appointed Her Lady of the Bedchamber and was at the time one of George's many mistresses.

The Duke of Wellington was later to suggest that she had personally brought pressure to bear to ensure that Caroline was selected to be George's prospective bride to be, a woman of such: "Indelicate manners, indifferent character and not very inviting performance, from a hope that disgust with a wife would secure constancy to a mistress."

Upon meeting Caroline for the first time, George was clearly disappointed and immediately ordered a large brandy. Caroline was likewise disappointed and was to tell Lord Malmesbury later that the Prince was very fat and nothing like as handsome as his portrait.

Once the formal introductions were over and it became clear they had nothing in common they both studiously avoided each other for the rest of the evening. From such unpromising beginnings things were only to get worse.

Nonetheless the wedding of George, Prince of Wales and Caroline of Brunswick would proceed and so amid much fanfare they were married in the Chapel Royal of St James Palace on 8 April 1795.

George, who had already decided that his wife was both unattractive and unhygienic was already drunk before he took his wedding vows. Indeed, Caroline was later to claim that he was so inebriated on their wedding night that he passed out in the fireplace, where she left him.

George later revealed to a friend that he only had sex with his wife three times twice on the first night and once on the second. He explained, "It required no small effort on my part to conquer my aversion to her person."

Despite a shared loathing for one another a daughter, Princess Charlotte Augusta was born nine months later. A week after her birth George made his Will bequeathing all his property to Maria Fitzherbert whilst making provision for his wife of just one shilling.

It was clear there was no future in the marriage and George and Caroline were soon living apart only ever communicating with each other via letter. In the meantime, George tried to restrict Caroline's access to their daughter whilst desperately seeking an annulment of the marriage.

In 1802, Caroline adopted a three-month-old boy named William Austin but the rumour soon began to circulate that he was in fact her illegitimate son by an unknown lover.

In 1806, under pressure from the Prince a secret Commission was established to investigate her behaviour but they were unable to discover anything improper in her behaviour other than her general deportment.

In 1810, George III fell ill again with porphyria, an illness undiagnosed at the time that made him delusional and seemingly mad. He had suffered from this illness for many years but in years past had once again come to his senses - but not on this occasion. The aged King was effectively retired, and George was made Prince Regent.

Caroline, in the meantime, was becoming the focus of opposition to the Prince Regent's lavish lifestyle and unlike her husband who had become used to being roundly booed she was cheered wherever she went.

The people liked her lack of airs and graces, her open familiarity and the vulgarian streak that so appalled the social elite. The fact that she was deprived of time with her daughter and George openly flaunted his mistresses in public only served to reinforce her reputation as the wronged woman.

George, who had always been dismayed at his own unpopularity, was simply confounded by the love the people seemingly had for this dreadful woman and her continued presence in the country not only haunted his every waking moment but was becoming a constitutional crisis.

Eventually after torturous negotiation Caroline was persuaded to leave Britain for an annual allowance of £35,000. On 8 August 1810, she departed for the Continent.

Caroline lived for a while in a villa near Lake Como in Italy before embarking upon a Mediterranean cruise with the man who was believed to be her lover, Bartolemeo Pergami. This apparent affair caused a scandal and if it were true then it would be grounds for a divorce. So in her absence the villa was ransacked by the Prince’s agents but other than rumpled and dirty bedclothes they could find nothing incriminating.

In November 1817, the Princess Charlotte Augusta died. George had neglected to tell Caroline of their daughter’s death and she only found out by chance. She was devastated by the news and never forgave George for his callous disregard for her feelings.

This was a time when divorce by mutual consent was not permitted in law and adultery either had to be proved or one of the parties involved had to admit to it. George through his representatives had been trying to cajole Caroline to consent to do this but there was no chance of that now.

On 29 January 1817, the aged and incapacitated George III died. Upon the Prince Regent's Coronation as King George IV, Caroline would be Queen. At George's behest, Parliament offered Caroline an increased allowance of £50,000 a year to simply stay away but she was determined to attend the Coronation and take up her rightful role as Queen of England.

Caroline’s return to England on 5 June 1821, saw riots and demonstrations occur in her support throughout the country and there were even rumours of disquiet within the army. Indeed, so unpopular was the new King that the Government even momentarily feared revolution.

Nonetheless, George was determined upon a divorce, and he had the evidence of her infidelities circumstantial though it was now brought to Westminster for further investigation. The previous year Parliament had introduced the "Pains and Penalties Bill" which if passed would strip Caroline of her title as Queen and dissolve the marriage.

The next legitimate Queen of England was now effectively put on trial and her relationship with Pergami was made public.

Witnesses came forward to say that they had been seen kissing, that she was often in a state of undress in his presence and that there was only one bed in the villa they shared. But the people just saw this as rank hypocrisy. George's affairs were common knowledge as were the sexual indiscretions of other prominent public figures.

The Pains and Penalties Bill passed comfortably through the House of Lords but it soon became apparent that it had no chance of passing through the House of Commons and so to save the Monarchy the humiliation of defeat it was withdrawn.

The Public Inquiry into Caroline's private life had been a fiasco for the Government and George's refusal to be reconciled with his wife was making a laughingstock of them all. Indeed, Caroline joked: “I have been accused of committing adultery with the husband of Mrs Fitzherbert”.

The affair was no joke for the Monarchy as hundreds of petitions had been organised in Caroline's support which gathered over a million signatures. She also campaigned hard on her own behalf and would address the crowds that would flock around her on every public appearance telling them: "As Queen, you will find in me a sincere friend to your liberties, and a zealous advocate of your rights.” Regardless of such fine words she had secretly agreed to accept Parliaments offer of £50,000 to return abroad but only with the proviso that she be permitted to attend the Coronation and be recognised as Queen. George refused to countenance any such thing and so did Parliament.

On 19 July 1821 the Prince Regent was crowned King George IV at Westminster Abbey while Caroline who turned up as she said she would was refused entry by guards at bayonet point. The Lord Chamberlain then ordered the doors closed and bolted.

Refused entry Caroline became hysterical and began banging on the doors with her fists and screaming obscenities. The watching crowd were shocked and appalled in equal measure while her use of profane language on such a solemn occasion saw her to begin to lose popular support for the first time. Later that same night she fell seriously ill.

Over the next three weeks her condition deteriorated and on 7 August, aged 53, she died. Buried in Brunswick the inscription on her tomb reads at her insistence: "Here lies Caroline, the Injured Queen of England.” The exact cause of her death remains unknown, but the rumour persists that she was poisoned.

Following Caroline's death, George IV's own health also went into steep decline. His devotion to the table saw his weight balloon and his heavy drinking led to mental decay and premature decrepitude. He found breathing difficult and would not rise from his bed for days on end.

By now so obese that he rarely appeared in public he lived in seclusion at Windsor Castle.

During his reign the prestige and the popularity of the Monarchy collapsed to an all-time low. The scandal of his marriage to Caroline of Brunswick was to dog him for the rest of his life and few people had a good word to say for him. Even the ultra-conservative Duke of Wellington felt moved to describe him as: “The worst man I ever fell in with in my entire life, the most selfish, the most false, the most ill-natured, and the most entirely without one redeeming quality.”

King George IV died on 26 June 1830, aged 67. The Times reported: “There never was an individual less regretted by his fellow creatures than this deceased King. What eye has wept for him? What heart has heaved one sob of un-mercenary sorrow? Selfishness is the true repellent of human sympathy. Selfishness feels no attachment, and invites none.”

He was little mourned.

Share this post: