Georgian Style

Posted on 1st July 2022

The Georgian Era was a time of great splendour and display when those of substance, and they were few, would promenade their finery for all to see. The cream of English society, the 1500 or so families that could trace a noble lineage known as the ‘Ton’ and those of the nouveau riche raised in status and emboldened of spirit by overseas trade and the expansion of Empire were eager that others should know of their privilege and power even on streets where the poverty in the air was absolute and resident in the very nostrils of those who breathed it.

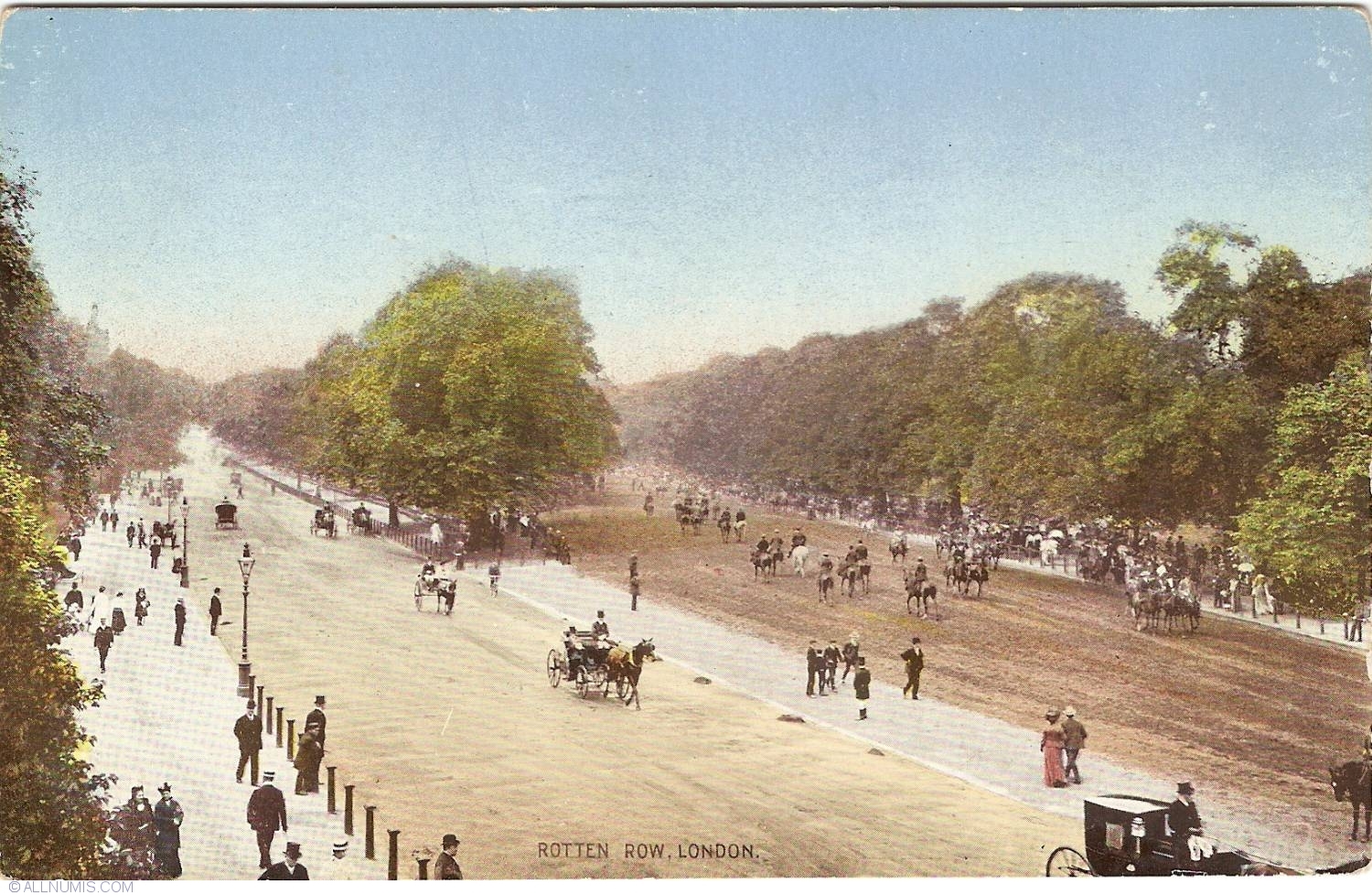

The highlight of any year was the London Season which ran from January to July though the summer months could be curtailed should the plague be in town. Hyde Park was the popular destination for daily entertainments and barely disguised illicit trysts for rich and poor alike. But it was the rich with parasol and cane, on horseback and in gilded carriage who set the scene. Nowhere else in Europe could the rich so flagrantly flaunt their wealth without fear of riot and revolution though they were not immune to robbery - a gentlemen, rarely went unarmed.

The place to be seen was Rotten Row, a gravel pathway lit with oil lamps at night created by William III to provide a safe route through Hyde Park where many an unfortunate traveller, fell victim to armed thieves and highwaymen. Created as the King’s Road the corruption of its name from the original French, Route du Roi, was at least one the common people could appreciate.

Having put themselves on display throughout the day, gentlemen for whom other priorities did not impinge upon their time, would retire to attend early evening soirees where they would take tea and eat cake before departing to prepare for the night-time ball, a lavish affair where the women resplendent in heels, silk stockings, powdered wigs and heavily brocaded dresses flirted with men for whom the boots could never be too shiny or the breeches too tight. But the peacock self-indulgence had a purpose, it provided the opportunity for young ladies to meet eligible bachelors, future husbands with prospects and a title to inherit – it was known as the ‘Marriage Mart.’

The fashion icons of the day were Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire who was famous for her high powdered and perfumed wigs adorned with coloured ribbons and ostrich feathers – a must look for the ladies of the day.

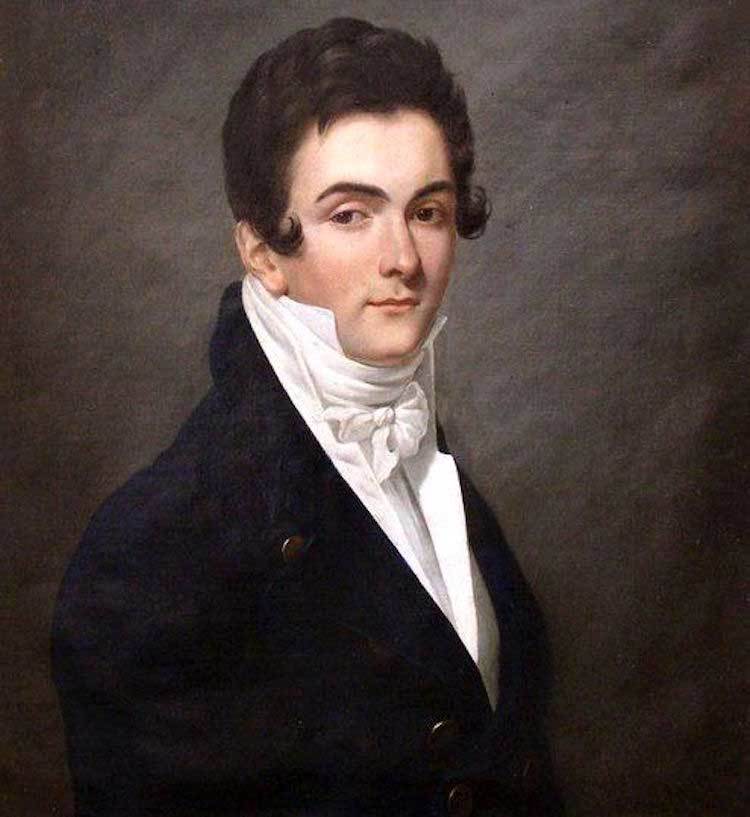

Her male equivalent was George Bryan ‘Beau’ Brummell, son of the Private Secretary to Prime Minister Lord North and close friend of the Prince Regent and future King George IV, a man who neglected his royal duties in favour of personal vanity.

The fate which had befallen the aristocracy in France during the revolution tempered the extravagance for a time. Marie Antoinette’s execution saw the ladies of England wear more modest and looser fitting muslin dresses rather than the lace and silk of old with their cleavages less prominent and hidden from sight.

Confidence was soon restored however, and Beau Brummell led the way with his love of dark coats over brilliant white linen shirts sprinkled with glitter and sewn with jewels that sparkled beneath the chandeliers, elaborately knotted neckerchiefs and knee length boots polished with champagne to within an inch of their lives. And he was no less extravagant in his claims than he was in his dress. He would tell the story of how he resigned his commission in the Royal Hussars when they were assigned to Manchester declaring that he could not bear to be in a place so lacking in style. He also claimed to spend five hours every day bathing and dressing.

Such was Beau Brummell’s fame and the praise heaped upon his shoulders that the Prince Regent would consult him on how to dress before appearing in public wanting less to be King than he did England’s foremost dandy.

His life took a turn for the worse however, when in July 1813, at a Masquerade Ball believing that the Prince Regent had deliberately snubbed him he referenced in a loud voice his excess of weight - the Prince never forgave him.

In any dispute between the future King and England’s most fashionable man there could be only one winner as Brummell was soon to discover. Deserted by his friends and patrons in 1816 he fled to France to avoid Debtors Prison. He remained well-connected enough to secure a job at the British Consulate in Caen but incapable of either sobriety or meaningful endeavour he soon found himself in a French Debtors Prisons. Those few friends still sympathetic to him paid for his release and begged him to return home to England but he refused. He died penniless in an asylum on 30 March 1840, aged 61, having been driven insane by syphilis.

Lady Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire had courted controversy all her life and not just for her outrageous fashion sense. She’d also had a series of torrid and very public affairs, was politically outspoken at a time when women were expected to keep their own counsel, was frequently seen drunk, and had an addiction to the card table and roulette wheel that by the time of her death aged just 48 in 1806, Saw her leave gambling debts the equivalent today of over £3,000,000.

The Prince Regent became King George IV on 29 January, 1820. He had long considered himself the handsomest Prince in Europe but now without Beau Brummell to guide him he felt lost and so sought constant validation. In the end, his increasingly absurd attempts to be admired made him a laughing-stock. So much so, that when the most lampooned Monarch in British history finally died on 26 June 1830, grossly overweight and barely able to stand, he was little mourned. In their obituary of him The Times Newspaper wrote:

"There never was an individual less regretted by his fellow creatures than this deceased King. What eye has wept for him? What heart has throbbed one heave of unmercenary sorrow? If he ever had a friend - a devoted friend in any rank of life - we protest that the name of him or her has ever reached us."

The extravagance and need it be said licentiousness of the Georgian Era, particularly the Regency period (1811-20) was soon replaced by more abstemious times particularly during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901) when a sense of propriety dominated and the making of money rather than the spending of it became the leitmotif of success and respectability.

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: