Gettysburg Address

Posted on 23rd May 2021

In the first week of July 1863, the bloodiest battle ever fought on American soil took place near the small town of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania. It would result in a Union victory but at the cost of nearly 50,000 killed, wounded and unaccounted for few could be in any doubt that the United States was in a struggle for its very existence.

Yet despite the victory at Gettysburg the war dragged on, the blood continued to flow and there appeared no imminent end to the conflict, and many began to doubt whether the preservation of the Union was worth all the treasure spent and lives lost. The man to blame was the President of course, and Abraham Lincoln was little admired or respected viewed by many as coarse, ill-educated and unequal to the task.

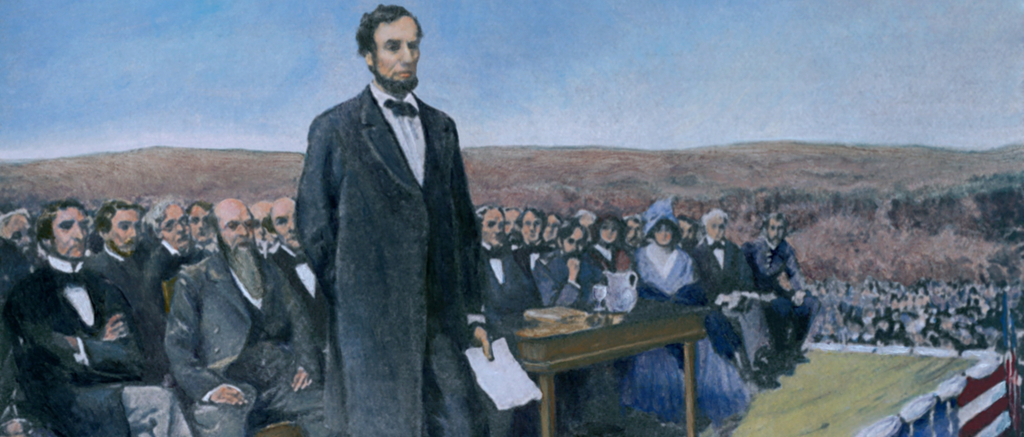

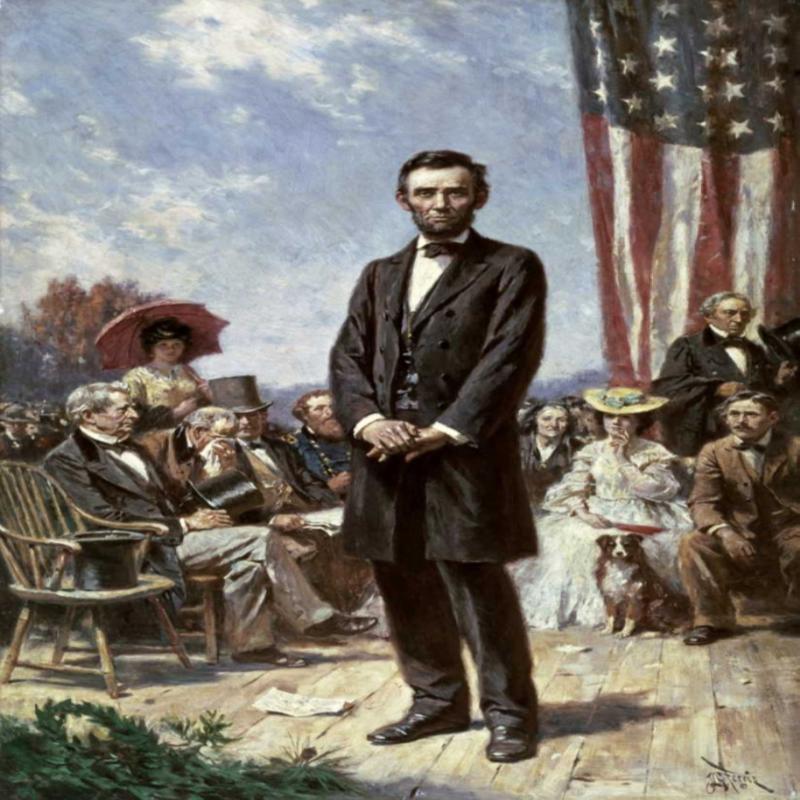

Four months later on November 19th, he travelled from Washington to dedicate the new military cemetery being constructed on the site of the old battlefield where in one short speech dismissed at the time as being disrespectful in its brevity would change opinion forever.

In the days prior to the dedication Lincoln had been ill. He was feverish, breathing with difficulty and was physically weak. Indeed, described as being drawn and haggard his appearance was much commented upon. He had it was said a ghastly pallor giving him a mournful appearance that was perhaps appropriate given the occasion but did little to inspire confidence.

It has since been suggested that the length of his speech was dictated by his physical inability to give much more. But then the President was not the main speaker that day, the principal address at Gettysburg was to be given by Edward Everett, the former Governor of Massachusetts and the best-known orator of his day. Even so, there was much excitement in the town at the prospect that the President might also say a few words and the crush around Lincoln was such that a space had to be created for him but considerably taller than most men he was not difficult to pick out in a crowd.

Upon the completion of Edward Everett’s oration, it was time for the President to say a few words, though most of those in attendance could not have imagined just how few. Despite clearly being unwell he spoke in a distinct and loud voice:

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who gave their lives that a nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow, this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us – that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain – that the nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

The response to his speech was mixed some of those present remembered it being greeted in utter silence, others that there was a small smattering of applause. Lincoln’s bodyguard recalled that the President said to him that “like a bad plough this speech won’t scour.”

He thought that he had said too little and that he had let everyone down, but the following day Edward Everett wrote to Lincoln: “I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea, of the occasion, in two hours as you did in two minutes.”

The reaction of the press to the President’s speech remained divided on political lines but was generally underwhelming and in some quarters scathing. The Democrat leaning Chicago Times wrote that: “The cheek of every American will tingle with shame as he reads the silly, flat, and dish-watery utterances of the man who has to be pointed out to intelligent foreigners as the President of the United States . . . is Mr Lincoln less refined than a savage? It was a perversion of history so flagrant that the most extended charity cannot view it as otherwise.”

The London Times was similarly scathing in its summation: “The ceremony was rendered ludicrous by some of the, sallies of that poor President Lincoln. Anything more dull and commonplace it would not be easy to produce.”

The Providence Daily Journal thought differently, however: “We know not where to look for a more admirable speech than the brief one the President made. It is often said that the hardest thing in the world is to make a five minute speech. But could the most elaborate and splendid oration, be more beautiful, more touching, more inspiring than those few words of the President.”

Abraham Lincoln had been the most divisive President in American history not only because he was hated in the South as the bringer of war but many in the North had grown little less hostile to his perceived failings and his obstinate refusal to negotiate an end to the war less than total victory. His appearance tall and ungainly and his homespun homilies which often irritated more than they amused only cast further doubt on his fitness for high office. How could this man ever be President at all let alone at a time of great national crisis?

Many thought his brief, if not terse, oration at a ceremony to honour those who had given their lives in the cause of the Union to be insulting. Subsequent events and the verdict of history has long since proved the doubters wrong.

Tagged as: Fact File

Share this post: