Gilles de Rais: A Medieval Killer

Posted on 11th August 2021

Gilles de Rais was a man of noble blood and a hero of the French Court who had fought alongside Joan of Arc at the Siege of Orleans and later the Siege of Paris after which he was permitted to wear the Royal Fleur-de-Lys on his coat of arms and made a Marshal of France at the age of just 25. He was a model of chivalry, handsome, brave and much admired but he also had a dark side which besides the obvious his frequent drunkenness and violent temper, few could have imagined.

He was born in 1404 at the family Castle at Machecoul and was a bright child who learned Latin when still young and would illuminate manuscripts for his own pleasure, but it was to the outdoor life that he was particularly drawn revelling in the rigours of physical exercise.

When he was still only eleven years of age both his mother and father died within a few months of each other and he along with his younger brother Rene de la Suze were placed in the care of their unscrupulous and ambitious grandfather Jean de Craon, who saw their adoption as an opportunity to enhance his social standing and personal wealth via the marriage bed.

On 30 November 1420, aged sixteen, Gilles was married to Catherine de Thouars, the Heiress to Poitou and the Vendee. She was soon pregnant and the marriage was to make both Gilles and his grandfather very rich men indeed.

The young Gilles could be both charming and charismatic, but his failings were evident and had not gone unnoticed. His courage on the battlefield however, led to doubts about his character being conveniently brushed aside for everyone agreed that Gilles was oblivious to danger and brave in the extreme. Decorated during the war against the English his citation read: “For his commendable services and many brave feats.”

The stoicism and discipline he displayed on the battlefield was sadly lacking in the way he conducted his private life, however. He drank heavily, liked to entertain his friends lavishly, and purchased jewels and fine silks at great expense. As a result, he was often short of money but under the protection of the Duke of Brittany he felt secure enough whenever poverty loomed to simply take the property of others.

In 1434, he constructed a chapel for himself where he would preside at prayers and give Mass dressed in extravagant robes that he had designed himself. The following year he put on a theatrical extravaganza that had a cast of 150 actors and engaged more than 500 others. It was all paid for from his own purse including the free food and wine he laid on for the spectators some of whom he had already paid to attend.

The entire affair almost bankrupted him, and he had to sell some family estates and much of his wife’s jewellery to ward it off.

By June 1435, his family had had enough and petitioned both the French King and Pope Eugene IV to curb his excesses. The Pope refused to get involved but on 2 July, a Royal Edict prevented him from selling any more of the family’s property.

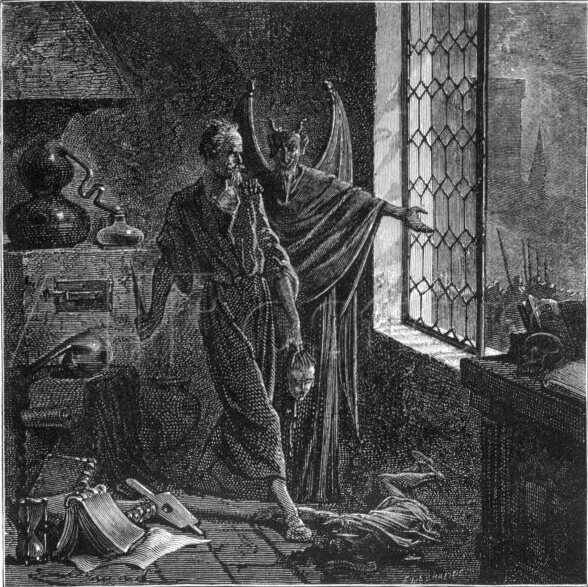

Not just faced with penury but with his reputation impugned Gilles life now took an even darker turn when he began to dabble in the occult and came under the tutelage of a sinister man named Francesco Prelati who had promised him that the occult was the means by which he would restore his fortunes. But his introduction to the dark arts had not predated his killing spree.

In the spring of 1432, a 12-year-old boy named Jeudon who was working as an apprentice to a local furrier Guillaume Hilairet was approached by a man calling himself Gilles de Sille (possibly de Rais himself) who asked him if he could take a message for him to the Castle at Machecoult. The boy did not want to go and Hilairet was reluctant to let him go but de Sille insisted – he was never seen again.

When de Rais was questioned about his disappearance he denied that the boy had ever been at Machecoult.

Over the next eight years a great many boys and girls would disappear in similarly mysterious circumstances and it was only by chance that their fate came to light.

On 15 May 1440, in a dispute over money de Rais abducted a priest from the Church of Saint-Etienne de Mer Morte and it was during an investigation conducted by the Bishop of Nantes into this incident that details were revealed under torture by de Rais manservant’s Corrilaut and Henriet of events at Machecoult.

With their testimony, and that of other witnesses the full horror of what de Rais had done was revealed and armed with this information the Bishop approached Jean V, Duke of Brittany, and demanded he face justice and be brought to trial. The Duke agreed and so on 29 July 1440, De Rais, Corrilaut and Henriet were arrested on charges of murder and the even more serious crime of heresy.

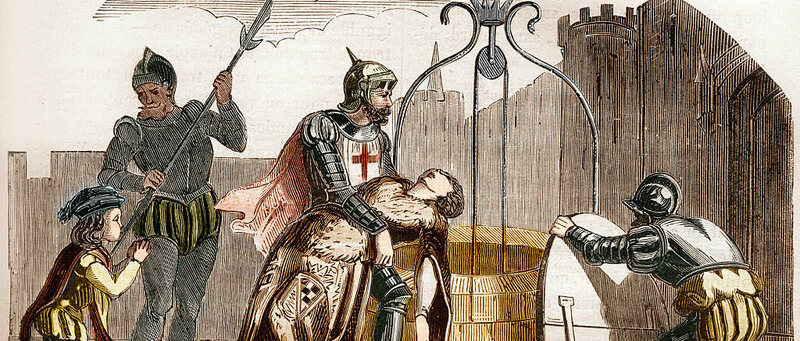

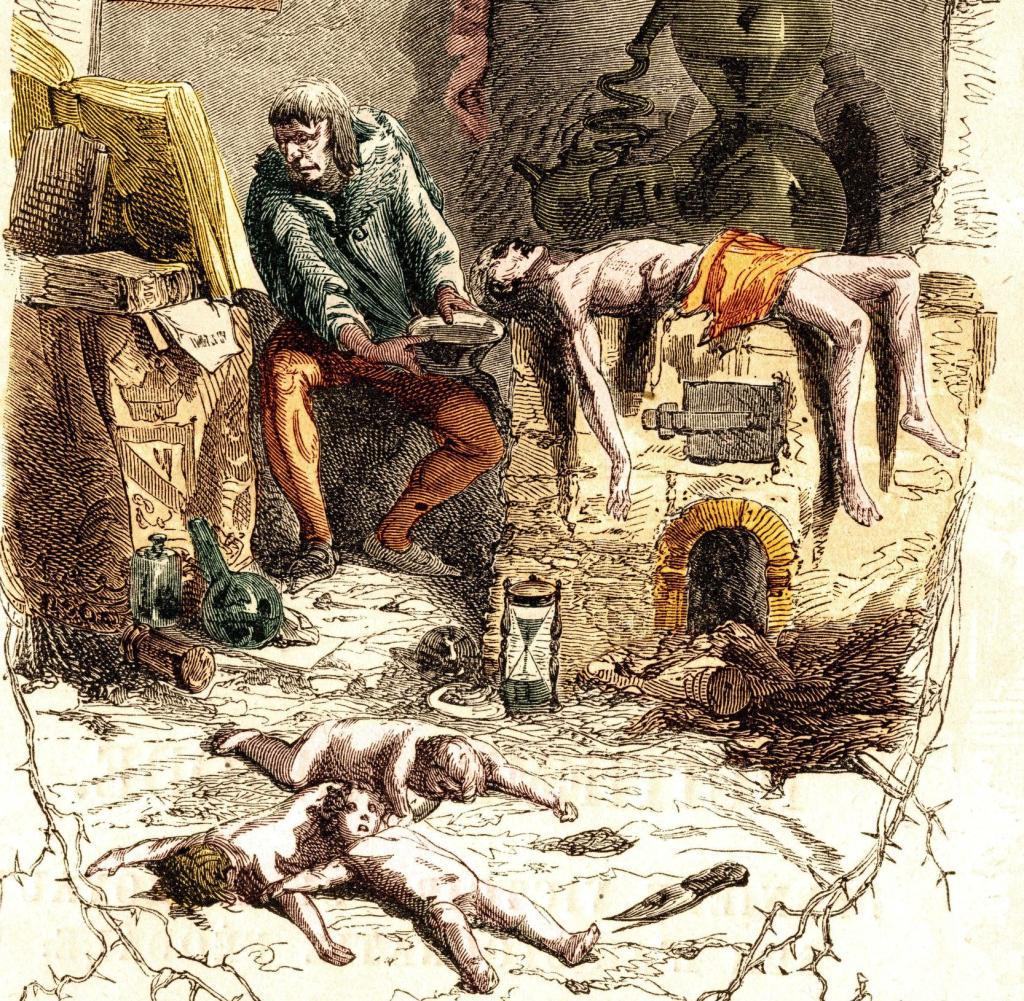

According to the testimony of witnesses De Rais would invite young boys and girls to his Castle with promises of food for their families, or he would simply abduct them late at night from nearby villages. Once in the Castle he proceeded to pamper them, they were bathed and dressed in the finest clothes before he would get them drunk and taken to his private chambers. There they were bound with ropes or hung on hooks and their mouths gagged to stop them crying out. He was sexually aroused by their struggling and the look of fear in their eyes and would proceed to masturbate on their stomach or thighs.

Corrilaut testified that his master would often masturbate on the bodies after they were dead, and that he disdained the victim’s sexual organs taking: “Infinitely more pleasure in debauching himself in this manner than using their natural orifice in the normal manner.”

De Rais himself confessed that: “When the children were dead I would hold up the heads of the most handsome ones to admire them.” He also took great delight in splitting open their stomachs and admiring their internal organs.

Most of his victims were killed with a large double-edged sword known as a braquemard and the bodies were then dismembered by his servants and burned in the fireplace of his private bed chamber. The room would then be heavily perfumed to disguise the smell of burned flesh.

That a man of noble birth, a close confidante of Joan of Arc, and a national hero could be guilty of such vile acts was deeply embarrassing to a Royal Court which now demanded both a fair trial and a speedy resolution.

The trial that had begun on 15 September 1440, was often delayed for those present to fully absorb the horror of what was being revealed, and indeed so graphic was much of the testimony that the Judge ordered it struck from the records.

As so many of the victims remains had been burned it was impossible to do an accurate body count. The Court, however, estimated that as many as 200 young boys and girls had been killed during de Rais’s eight-year reign of terror.

On 23 October 1440, Corrilaut and Henriet were condemned to death to be followed two days later by de Rais who was found guilty of murder and heresy. His sentence was to be hanged until choked and then burned to death in the presence of the relatives of those of his victims who could be identified. The sentences were to be carried out on 26 October.

Gilles de Rais requested to be the first to die and given his rank and his previous service to France his request was granted. Before he was executed, he addressed the crowd and begged their forgiveness. He then turned to his two accomplices and urged them to be brave and not fear death but to think instead of their coming salvation.

He was then hanged until barely conscious before being lowered back onto an already burning scaffold.

It was reported that he made no sound and was quickly consumed by the flames.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: